As I’ve noted in each of these posts, the fundamental claim we are evaluating here is this one, made baldly by George R.R. Martin:

As I’ve noted in each of these posts, the fundamental claim we are evaluating here is this one, made baldly by George R.R. Martin:

The Dothraki were actually fashioned as an amalgam of a number of steppe and plains cultures … Mongols and Huns, certainly, but also Alans, Sioux, Cheyenne, and various other Amerindian tribes … seasoned with a dash of pure fantasy.

We may, I think, now safely dismiss this statement as false. What we have found is that the Dothraki do not meaningfully mirror either Steppe or Plains cultures. They do not mirror them in dress, nor in systems of subsistence, nor in diet, nor in housing, nor in music, nor in art, nor in social structures, nor in leadership structures, nor in family structures, nor in demographics, nor in economics, nor in trade practices, nor in laws, nor in marriage customs, nor in attitudes towards violence, nor in weapons, nor in armor, nor in strategic way of war, nor in battle tactics.

We might say he has added “dashes” of pure fantasy until the “dash” is the entire soup, but the truth is clearly the reverse: Martin has sprinkled a little bit of water on a barrel of salt and called it just a dash of salt. There is no historical root source here, but instead pure fantasy which – because racist stereotypes sometimes connect, in thin and useless ways, to actual history – occasionally, in broken-clock fashion, manages to resemble the real thing.

It seems as though the best we might say of what Martin has right is that these are people who are nomads that ride horses and occasionally shoot bows. The rest – which as you can see from the list above there, is the overwhelming majority – has functionally no connection to the actual historical people. And stunningly, somehow, the show – despite its absolutely massive budget, despite the legions of scrutiny and oversight such a massive venture brings – somehow is even worse, while being just as explicit in tying its bald collection of 1930s racist stereotypes to real people who really exist today.

Instead, the primary inspiration for George R.R. Martin’s Dothraki seems to come from deeply flawed Hollywood depictions of nomadic peoples, rather than any real knowledge about the peoples themselves. The Dothraki are not an amalgam of the Sioux or the Mongols, but rather an amalgam of Stagecoach (1939) and The Conqueror (1956). When it comes to the major attributes of the Dothraki – their singular focus on violent, especially sexual violence, their lack of art or expression, their position as a culture we primarily see “from the outside” as almost uniformly brutal (and in need of literally the whitest of all women to tame and reform it) – what we see is not reflected in the historical people at all but is absolutely of a piece with this Hollywood legacy.

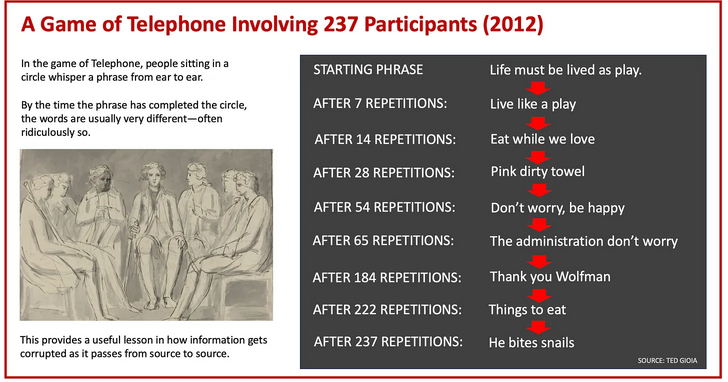

But Martin has done more damage than simply watching The Mongols (1961) would today. He has taken those old, inaccurate, racially tinged stereotypes and repackaged them, with an extra dash of contemporary cynicism to lend them the feeling of “reality” and then used his reputation as a writer of more historically grounded fantasy (a reputation, I think we may say at this point, which ought to be discarded; Martin is an engaging writer but a poor historian) to give those old stereotypes the air of “real history” and how things “really were”. And so, just as Westeros became the vision of the Middle Ages that inhabits the mind of so many people (including quite a few of my students), the Dothraki become the mental model for the Generic Nomad: brutal, sexually violent, uncreative, unartistic, uncivilized.

And as I noted at the beginning of this series, Martin’s fans have understood that framing perfectly well. The argument given by both the creators themselves, often parroted by fans and even repeated by journalists is that A Song of Ice and Fire‘s historical basis is both a strike in favor of the book because they present a “more real” vision of the past but also a flawless defense against any qualms anyone might have over the way that the fiction presents violence (especially its voyeuristic take on sexual violence) or its cultures. No doubt part of you are tired of seeing that same “amalgam” quote over and over again at the beginning of every single one of these essays, but I did that for a reason, because it was essential to note that this assertion is not merely part of the subtext of how Martin presents his work (although it is that too), but part of the actual text of his promotion of his work.

And it is a lie. And I want to be clear here, it is not a misunderstanding. It is not a regrettable implication. It is not an unfortunate blind-spot of ignorance. It is a lie, made repeatedly, now by many people in both the promotion of the books and the show who ought to have known better. And it is a lie that has been believed by millions of fans.

One thing that I hope is clear from this treatment is just how trivial the amount of research I’ve done here was. Certainly, it helped that I was familiar with Steppe nomads already and that I knew who to ask to be pointed in the direction of information. Nevertheless, everything I’ve cited here is available in English and it is all relatively affordable (I actually own all of the books cited here; thanks to my Patrons for making that possible, especially since getting materials from the library is slower in the days of COVID-19; nevertheless, the point here is that they are not obscure tomes). Much of it – Ratchnevsky on Chinggis Khan, Secoy and McGinnis on Great Plains warfare – were already available well before the 1996 publication of A Game of Thrones. 1996 was not some wasteland of ignorance that might have made it impossible for Martin to get good information! For an easy sense of what a dedicated amateur with film connections might have learned in 1996, you could simply watch Ken Burns’ The West, which came out the same year. I am not asking Martin to become a historian (though I am asking him to stop representing himself as something like one), I am asking him to read a historian.

Instead of doing that basic amount of research, or simply saying that the peoples of Essos were made up cultures unconnected with the real thing, Martin and the vast promotional apparatus at HBO opted to lie about some real cultures and then to put hundreds of millions of dollars into promoting that lie.

And I want to be clear, these are real people! I know, depending on where you live, “Mongols” and “Sioux” and “Cheyenne” may feel as distant and fanciful as “Rohirrim” or “Hobbits” or else they may feel like “long-lost” peoples. But these were real people, whose real descendants are alive today. And almost all of them face discrimination and abuse, sometimes informally, sometimes through state action, often as a result of these very lingering racist stereotypes.

In that context, declaring that the Dothraki really do reflect the real world (I cannot stress that enough) cultures of the Plains Native Americans or Eurasian Steppe Nomads is not merely a lie, but it is an irresponsible lie that can do real harm to real people in the real world. And that irresponsible lie has been accepted by Martin’s fans; he has done a grave disservice to his own fans by lying to them in this way. And of course the worst of it is that the lie – backed by the vast apparatus that is HBO prestige television – will have more reach and more enduring influence than this or any number of historical “debunking” essays. It will befuddle the valiant efforts of teachers in their classrooms (and yes, I frequently encounter students hindered by bad pop-pseudo-history they believe to be true; it is often devilishly hard to get students to leave those preconceptions behind), it will plague efforts to educate the public about these cultures of their histories. And it will probably, in the long run, hurt the real descendants of nomads.

But this is exactly why I think it is important for historians to engage with the culture and to engage with depictions like this. Because these lies have consequences and someone ought to at least try to tell the truth. With luck, even with my only rudimentary knowledge, I have done some of that here, by presenting a bit more of the richness and variety of historical (and in some cases, present-day) horse-borne nomadic life, in both North America and Eurasia.

Because there is and was a lot more to nomads than just “that Dothraki horde”.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: That Dothraki Horde, Part IV: Screamers and Howlers”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-01-08.