Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 29 Sept 2023The Byzantines (Blue’s Version) – a project that took an almost unfathomable amount of work and a catastrophic 120+ individual maps. I couldn’t be happier.

SOURCES & Further Reading:

“Byzantium” I, II, and III by John Julius Norwich, The Byzantine Republic: People and Power in New Rome by Anthony Kaldellis, The Alexiad by Anna Komnene, Osman’s Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire by Caroline Finkel, Sicily: An Island at the Crossroads of History by John Julius Norwich, A History of Venice by John Julius Norwich. I also have a degree in classical civilization.Additionally, the most august of thanks to our the members of our discord community who kindly assisted me with so much fantastic supplemental information for the scripting and revision process: Jonny, Catia, and Chehrazad. Thank you for reading my nonsense, providing more details to add to my nonsense, and making this the best nonsense it can be.

(more…)

January 13, 2024

History RE-Summarized: The Byzantine Empire

January 1, 2024

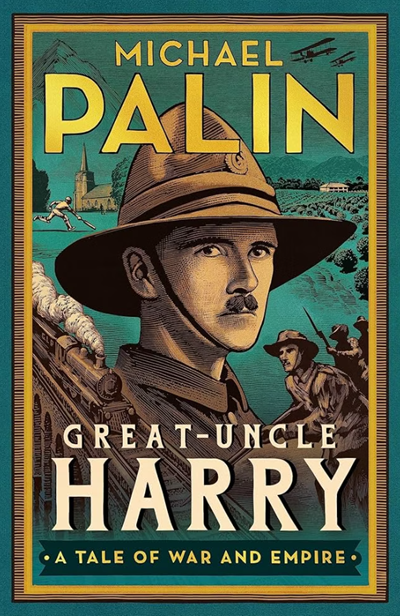

Michael Palin’s Great-Uncle Harry

In The Critic, Peter Caddick-Adams reviews Michael Palin’s Great-Uncle Harry:

The first of last week’s volumes nestling on my desk, with its immediately identifiable Ripping Yarns cover illustration, was Sir Michael Palin’s story of his forebear, Great Uncle Harry, who travelled the world but disappeared on the Somme. Here, I felt an immediate connection, not least because Michael, I and his Great Uncle Harry Palin had hauled ourselves through the same academy of learning, Shrewsbury School, though at different times. There are plenty of 1914-18 memoirs and tributes around, but this is one of the best. The further the Great War (as it used to be called) recedes, the more we seem to need to torture ourselves with the staggering sacrifices it involved. I read my copy over Remembrance weekend, which made it doubly poignant.

In Great Uncle Harry, Palin’s gift is to give us the hinterland of his ancestor. Many First World War authors, here I could mention the great Lyn Macdonald, Richard Holmes and Martin Middlebrook, all of whom I place on pedestals, provide us with erudite studies, laced with gripping eyewitness accounts. I find myself doing the same with 1939-45, but of necessity there is no room to give the brave and the damned a back story. They are parachuted into the text. They fight and live or die and exit stage left. It is refreshing, therefore, to hold the hand of a first war warrior from birth unto death. Palin was lucky his Great Uncle Harry kept a series of notebooks and diaries of his time in khaki, and was able to research his globe-trotting years before battle. Our man was brought up in Herefordshire, and after school drifted out to British India. He had two stints, first working as a railway manager and latterly as overseer on tea plantations. The reader is fortunate that Palin the documentary-maker filmed in both environments and is able to look over his forebear’s shoulder and summon up the Edwardian social standards of the day, with its solar topees and chota pegs (sunset whiskeys), its heat and its dust. Palin the younger’s many diaries and written travelogues, of which I find New Europe (2007) the best, are equally good.

But Great Uncle Harry Palin was restless. The youngest and most headstrong of seven, he flounced out of each of his two jobs serving the Raj, and ended up trying his hand at farming in New Zealand. There he seemed more settled, but not quite. The Palin under the microscope, notes his great nephew, was one of the first to volunteer for war service with the 12th (Nelson) Regiment, a South Island infantry outfit, in August 1914 and sailed with them overseas, initially to Egypt. There they were absorbed into the Canterbury Battalion, and deployed to Gallipoli, from which Great Uncle Harry emerged without a scratch.

Gallipoli is a conjurer’s name. Now known by the Turks as their Gelibolu Peninsula, overlooking the ancient Hellespont (today’s Dardanelles Strait), its southern tip lies 200 miles from what was then Turkey’s capital, Constantinople, officially Istanbul after 1930. Only since the 1990s has this strategically significant sliver of land, across the Dardanelles from ancient Troy, and guarding entry to the Bosphorus and Black Sea, been opened up for tourists. The 1915 operation was dreamt up by Winston Churchill to break the stalemate of the Western Front. He advocated a naval advance on Constantinople, as a way of knocking the Austro-German alliance out of the war. Such a stratagem would then have offered Paris and London the ability to supply the troops of Tsar Nicholas the Last with modern arms and munitions to prevail against the Central Powers.

Instead of breaking the Western Front, Gallipoli broke Churchill. It was a campaign endlessly refought in the inter-war years, which generally concluded that amphibious warfare had no future, though Lieutenant Colonel George S. Patton in his 1936 General Staff study, The Defense of Gallipoli, found it fascinating. It was one reason why the allies had no maritime landing capability in 1939-40, to Britain’s detriment at Dunkirk, and later Germany’s disadvantage when planning a seaborne assault against southern England. Valuable lessons of what to do, and not to do, had to be relearned before D-Day in 1944 could be a success. My own assessment is right idea, wrong commanders. Gallipoli might have offered the success Churchill desired, but was executed poorly.

The original plan had been to overwhelm Constantinople with battleships, and there is evidence that the Turks were preparing to surrender. However, the Franco-British war fleet encountered German-supplied Krupp cannon along both shores of the Dardanelles and a minefield in the middle, and suffered catastrophic losses. A land campaign was then initiated to clear the Turkish land-based defences. This should have been foreseen and a simultaneous, rather than sequential, maritime-land attack might well have delivered the goods.

Instead, the few Turkish defenders on Gallipoli could see a landing was imminent, called in reinforcements and dug trenches ferociously. On the peninsula, amidst scrub, trench and memorials lie scattered British, Commonwealth, Ottoman and French (yes, they were there too) cemeteries, hinting at stirring tales of derring-do. Last time I was there, I encountered not only rifle cartridges, pieces of pottery rum jars, and shell cases, but human bones. My guide observed, “Probably wild pigs dislodging the topsoil. It happens all the time.” An indication of the 300,000 Allied and 255,000 Turkish killed, wounded and missing in a campaign where illness often took as many as combat wounds. Along the western coast, amidst shards of amphorae from pre-history, lie many wrecks associated with the 1915 campaign in crystal-clear water. It remains high on my recommended battlefields to visit.

December 30, 2023

Building the Walls of Constantinople

toldinstone

Published 15 Sept 2023This video, shot on location in Istanbul, explores the walls of Byzantine Constantinople — and describes how they finally fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

(more…)

December 6, 2023

QotD: What Charles VIII brought back from his Naples vacation

… the basic formula for what would become gunpowder (saltpeter, charcoal, and sulfur in a roughly 75%, 15%, 10% mixture) was clearly in use in China by 1040 when we have our first attested formula, though saltpeter had been being refined and used as an incendiary since at least 808. The first guns appear to be extrapolations from Chinese incendiary “fire lances” (just add rocks!) and the first Chinese cannon appear in 1128. Guns arrive in Europe around 1300; our first representation of a cannon is from 1326, while we hear about them used in sieges beginning in the 1330s; the Mongol conquest and the sudden unification of the Eurasian Steppe probably provided the route for gunpowder and guns to move from China to Europe. Notably, guns seem to have arrived as a complete technology: chemistry, ignition system, tube and projectile.

There was still a long “shaking out” period for the new technology: figuring out how to get enough saltpeter for gunpowder (now that’s a story we’ll come back to some day), how to build a large enough and strong enough metal barrel, and how to actually use the weapons (in sieges? against infantry? big guns? little guns?) and so on. By 1453, the Ottomans have a capable siege-train of gunpowder artillery. Mehmed II (r. 1444-1481) pummeled the walls of Constantinople with some 5,000 shots using some 55,000 pounds of gunpowder; at last Theodosius’ engineers had met their match.

And then, in 1494, Charles VIII invaded Italy – in a dispute over the throne of Naples – with the first proper mobile siege train in Christendom (not in Europe, mind you, because Mehmed had beat our boy Chuck here by a solid four decades). A lot of changes had been happening to make these guns more effective: longer barrels allowed for more power and accuracy, wheeled carriages made them more mobile, trunnions made elevation control easier and some limited degree of caliber standardization reduced windage and simplified supply (though standardization at this point remains quite limited).

The various Italian states, exactly none of whom were excited to see Charles attempting to claim the Kingdom of Naples, could have figured that the many castles and fortified cities of northern Italy were likely to slow Charles down, giving them plenty of time to finish up their own holidays before this obnoxious French tourist showed up. On the 19th of October, 1494, Charles showed up to besiege the fortress at Mordano – a fortress which might well have been expected to hold him up for weeks or even months; on October 20th, 1494, Charles sacked Mordano and massacred the inhabitants, after having blasted a breach with his guns. Florence promptly surrendered and Charles marched to Naples, taking it in 1495 (it surrendered too). Francesco Guicciardini phrased it thusly (trans. via Lee, Waging War, 228),

They [Charles’ artillery] were planted against the Walls of a Town with such speed, the Space between the Shots was so little, and the Balls flew so quick, and were impelled with such Force, that as much Execution was done in a few Hours, as formerly, in Italy, in the like Number of Days.

The impacts of the sudden apparent obsolescence of European castles were considerable. The period from 1450 to 1550 sees a remarkable degree of state-consolidation in Europe (broadly construed) castles, and the power they gave the local nobility to resist the crown, had been one of the drivers of European fragmentation, though we should be careful not to overstate the gunpowder impact here: there are other reasons for a burst of state consolidation at this juncture. Of course that creates a run-away effect of its own, as states that consolidate have the resources to employ larger and more effective siege trains.

Now this strong reaction doesn’t happen everywhere or really anywhere outside of Europe. Part of that has to do with the way that castles were built. Because castles were designed to resist escalade, the walls needed to be built as high as possible, since that was the best way to resist attacks by ladders or towers. But of course, given a fixed amount of building resources, building high also means building thin (and European masonry techniques enabled tall-and-thin construction with walls essentially being constructed with a thick layer of fill material sandwiched between courses of stone). But “tall and thin”, while good against ladders, was a huge liability against cannon.

By contrast, city walls in China were often constructed using a rammed earth core. In essence, earth was piled up in courses and packed very tightly, and then sheathed in stone. This was a labor-intensive building style (but large cities and lots of state capacity meant that labor was available), and it meant the walls had to be made thick in order to be made tall since even rammed earth can only be piled up at an angle substantially less than vertical. But against cannon, the result was walls which were already massively thick, impossible to topple over and the earth-fill, unlike European stone-fill, could absorb some of the energy of the impact without cracking or shattering. Even if the stone shell was broken, the earth wouldn’t tumble out (because it was rammed), but would instead self-seal small gaps. And no attacker could hope that a few lucky hits to the base of a wall built like this would cause it to topple over, given how wide it is at the base. Consequently, European castle walls were vulnerable to cannon in a way that contemporary walls in many other places, such as China, were not. Again, path dependence in fortification matters, because of that antagonistic co-evolution.

In the event, in Italy, Charles’ Italian Vacation started to go badly almost immediately after Naples was taken. A united front against him, the League of Venice, formed in 1495 and fought Charles to a bloody draw at Fornovo in July, 1495. In the long-term, French involvement would draw in the Habsburgs, whose involvement would prevent the French from making permanent gains in a series of wars in Italy lasting well into the 1550s.

But more relevant for our topic was the tremendous shock of that first campaign and the sudden failure of defenses which had long been considered strong. The reader can, I’d argue, detect the continued light tremors of that shock as late as Machiavelli’s The Prince (1532, but perhaps written in some form by 1513). Meanwhile, Italian fortress designers were already at work retrofitting old castles and fortifications (and building new ones) to more effectively resist artillery. Their secret weapon? Geometry.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part IV: French Guns and Italian Lines”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-12-17.

October 17, 2023

Why WW1 Cavalry Was Essential On The Battlefield

The Great War

Published 13 Oct 2023The First World War was a catalyst for modern warfare with tanks, poison gas, flamethrowers and more. Cavalry didn’t have a place anymore on the modern battlefield – or so the common misconception goes. In this video we show how useful cavalry still was in WW1.

(more…)

May 4, 2023

Fierce fighting on Gallipoli … before WW1

Bruce Gudmundsson outlines the operations of Ottoman Empire forces defending “Turkey in Europe” against Greek and Bulgarian invasion (in alliance with Serbia and Montenegro) in 1913:

In the English speaking world, the name Gallipoli invariably evokes memories of the great events of 1915 and 1916. A location of such strategic importance, however, rarely serves as the site of a single battles. Two years before the landings of the British, Indian, Australian, and New Zealand troops on the south-west portion of the the peninsula (and the concurrent French landings on the nearby mainland of Asia Minor near the ruins of the ancient city of Troy), Ottoman soldiers defended the Dardanelles against the forces of the Balkan League.

By the end of January of 1913, the combined efforts of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria had driven Ottoman forces from most of “Turkey in Europe”. Indeed, the only intact Ottoman formations on European soil were those trapped in the fortress of Adrianople, those holding the fortified line just west of Constantinople, and those that had recently arrived at Gallipoli.

Soon after arriving, the Ottoman forces on Gallipoli began to build a belt of field fortifications across the narrowest part of the peninsula, a line some five kilometers (three miles) west of the the town of Bolayir. At the same time, they occupied outposts some twenty kilometers east of the line, at the place where the peninsula connected to the mainland.

On 4 February 1913, the Bulgarians attacked. On the first day of this attack, they drove in the Ottoman outposts. On the second day, they broke through a hastily erected line of resistance, thereby convincing the Ottoman forces in front of them to evacuate Bolayir. However, rather than taking the town, or otherwise attempting to exploit their victory, they withdrew to positions some ten kilometers (six miles) east of the Ottoman earthworks.

While the Ottoman land forces returned to the earthworks along the neck of the Peninsula, ships of the Ottoman Navy operating in the Sea of Marmora located, and began to bombard, the Bulgarian forces near the coast. This caused the Bulgarians to move inland, where they took up, and improved, new positions on the rear slopes of nearby hills.

On 9 February, the Ottomans launched a double attack. While the main body of the Ottoman garrison of Gallipoli advanced overland, a smaller force, supported by the fire of Ottoman warships, landed on the far side of the Bulgarian position. Notwithstanding the advantages, both numerical and geometric, enjoyed by the Ottoman attackers, this pincer action failed to destroy the Bulgarian force. Indeed, in the course of two failed attacks, the Ottomans suffered some ten thousand casualties.

Though the Ottoman maneuver failed to dislodge the Bulgarians from their trenches, the two-sided attack convinced the Bulgarian commander to seek ground that was, at once, both easier to defend against terrestrial attack and less vulnerable to naval gunfire. He found this on the east bank of a river, thirteen kilometers (eight miles) northeast of Bolayir and ten kilometers (six miles) north of the place where the Ottoman landing had taken place.

April 10, 2023

The Crimean Naval War at Sea – Battleships, Bombardments and the Black Sea

Drachinifel

Published 5 Apr 2023Today we take a look at most of the naval theaters of the Crimean War on conjunction with the fine people @realtimehistory find their video here: Last Crusade or F…

(more…)

April 8, 2023

Russia’s Last Crusade – The Crimean War 1853-1856

Real Time History

Published 7 Apr 2023The Crimean War between the Ottoman Empire and Russia (and later the UK and France) has been called the last crusade and the first modern war at the same time.

(more…)

October 23, 2022

T. E. Lawrence: The True Lawrence of Arabia

Biographics

Published 13 Jun 2022

(more…)

October 8, 2022

Prelude to WW1 – The Balkan Wars 1912-1913

The Great War

Published 7 Oct 2022The Balkan Wars marked the end of Ottoman rule in Southeastern Europe, and they involved several countries that would join the First World War just a few years later. A complicated alliance between Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria and Greece imploded over disagreement of the war spoils after defeating the Ottomans. This led to the 2nd Balkan War and also created much resentment that would play a role between 1914 and 1918 too.

(more…)

September 29, 2022

The History of Cyprus Explained in 10 minutes

Epimetheus

Published 24 May 2022The history of Cyprus explained from ancient times to modern.

(more…)

August 20, 2022

How Turkey Fought a WW1 Peace Treaty – The Greek-Turkish War 1919-1923

The Great War

Published 19 Aug 2022The defeat of the Ottoman Empire in 1918 meant that it got its own peace treaty like the other three Central Powers. But the emerging Turkish National Movement under Mustafa Kemal resisted the Treaty of Sevres and occupation by various Entente Powers. Their successful resistance led to the creation of modern Turkey and the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923.

(more…)

January 5, 2022

History Summarized: The Ottoman Empire

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 5 Oct 2018Leave it to the furniture boys to pioneer a Comfort-First attitude towards Imperialism.

Join Blue in investigating the history of the Ottoman empire, and find out why “The Sick Man of Europe” is more than their nickname implies.

Further reading: Osman’s Dream by Caroline Finkel

Famous Turkish Song — Gunduz Gece: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2UcbH…

PATREON: www.patreon.com/OSP

MERCH LINKS:

Shirts – https://overlysarcasticproducts.threa…

All the other stuff – http://www.cafepress.com/OverlySarcas…Find us on Twitter @OSPYouTube!

December 28, 2021

The Bubblegum History … of Chewing Gum

TimeGhost History

Published 27 Dec 2021Ancient Finns, angry Ottomans, a one-legged Mexican general, and scouring soap — that’s the story of modern chewing gum in a nutshell!

Hosted by: Indy Neidell and Spartacus Olsson

Written by: Indy Neidell

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Maria Kyhle

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Edited by: Karolina Dołęga

Sound design: Marek KamińskiSources:

– Birch Bark photo courtesy of Jerzy Opioła https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi…

– Mastic tears photo courtesy of פארוק https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mastic_…

– Mexican Cession map courtesy of Kballen https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi…

– Peter Gabriel, Chateau Neuf, Oslo, Norway courtesty of Helge Øverås https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pe…

– Promotional Chiclets courtesy of Coolshans https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi…Soundtracks from Epidemic Sound:

– “Ancient Saga” – Max Anson

– “Master of the Hurricane” – Rockin’ For Decades

– “Home on the Prairie” – Sight of Wonders

– “Cocktail Hour” – The Fly Guy FiveArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

December 20, 2021

Foreshadowing WW1 – Italo-Turkish War 1911-1912 I THE GREAT WAR

The Great War

Published 17 Dec 2021Sign up for Audible and get 60% off your first three months: https://audible.com/greatwar or text

greatwarto 500-500The Italo-Turkish War 1911 was one of the last classic imperial wars over colonial processions between two great powers. But it was in many ways also a first glimpse into what would come during the First World War: trenches, artillery, combat aircraft, motorboat attacks. This war in Ottoman Libya was fought between the Italian Army and Ottoman-led local Senussi forces.

» SUPPORT THE CHANNEL

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/thegreatwar» THANKS TO OUR CO-PRODUCERS

John Ozment, James Darcangelo, Jacob Carter Landt, Thomas Brendan, Kurt Gillies, Scott Deederly, John Belland, Adam Smith, Taylor Allen, Rustem Sharipov, Christoph Wolf, Simen Røste, Marcus Bondura, Ramon Rijkhoek, Theodore Patrick Shannon, Philip Schoffman, Avi Woolf,» SOURCES

Askew, William C., Europe and Italy’s Acquisition of Libya, 1911-1912, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1942)Caccamo, Francesco, “Italy, Libya and the Balkans” in Geppert, Dominik; Mulligan, William & Rose, Andreas (eds.), The Wars before the Great War: Conflict and International Politics Before the Outbreak of the First World War, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016)

Childs, Timothy W, Italo-Turkish Diplomacy and the War Over Libya, 1911–1912, (Leiden: Brill, 1990)

Griffin, Ernest H., Adventures in Tripoli: A Doctor in the Desert (London: Philip Allen & Co., 1924)

Hindmarsh. Albert E. & Wilson, George Grafton, “War Declared and the Use of Force”, Proceedings of the American Society of International Law at Its Annual Meeting (1921-1969) Vol. 32 (1938)

McCollum Jonathan, “Reimagining Mediterranean Spaces: Libya and the Italo-Turkish War, 1911-1912”, in Mediterraneo cosmopolita, 23 (3) 2015.

McMeekin, Sean, The Ottoman Endgame (Penguin, 2013).

Paris, Michael, “The First Air Wars – North Africa and the Balkans, 1911-13”, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1991)

Stephenson, Charles, A Box of Sand: the Italo-Ottoman War 1911-1912: the First Land, Sea and Air War, (Ticehurst: Tattered Flag Press, 2014)

Tittoni, Renato, The Italo-Turkish War (1911-12). Translated and Compiled from the Reports of the Italian General Staff, (Kansas City, MO: Frank Hudson Publishing Company, 1914)

Uyar, Mesut, The Ottoman Army and the First World War, (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021)

Vandervort, Bruce, Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa 1830-1914, (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1998)

Wilcox, Vanda, Italy in the Era of the Great War, (Leiden: Brill, 2018)

Wilcox, Vanda, “The Italian Soldiers’ experience in Libya, 1911-12” in Geppert, Dominik; Mulligan, William & Rose, Andreas (eds.), The Wars before the Great War: Conflict and International Politics Before the Outbreak of the First World War, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016)

»CREDITS

Presented by: Jesse Alexander

Written by: Mark Newton, Jesse Alexander

Director: Toni Steller & Florian Wittig

Director of Photography: Toni Steller

Sound: Toni Steller

Editing: Jose Gamez

Motion Design: Philipp Appelt

Mixing, Mastering & Sound Design: http://above-zero.com

Research by: Mark Newton

Fact checking: Florian WittigChannel Design: Yves Thimian

Contains licensed material by getty images

All rights reserved – Real Time History GmbH 2021