Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 29 Sept 2023The Byzantines (Blue’s Version) – a project that took an almost unfathomable amount of work and a catastrophic 120+ individual maps. I couldn’t be happier.

SOURCES & Further Reading:

“Byzantium” I, II, and III by John Julius Norwich, The Byzantine Republic: People and Power in New Rome by Anthony Kaldellis, The Alexiad by Anna Komnene, Osman’s Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire by Caroline Finkel, Sicily: An Island at the Crossroads of History by John Julius Norwich, A History of Venice by John Julius Norwich. I also have a degree in classical civilization.Additionally, the most august of thanks to our the members of our discord community who kindly assisted me with so much fantastic supplemental information for the scripting and revision process: Jonny, Catia, and Chehrazad. Thank you for reading my nonsense, providing more details to add to my nonsense, and making this the best nonsense it can be.

(more…)

January 13, 2024

History RE-Summarized: The Byzantine Empire

December 31, 2023

Justinian I

In The Critic, George Woudhuysen reviews Justinian: Emperor, Soldier, Saint, by Peter Sarris:

The emperor Justinian did not sleep. So concerned was he for the welfare of his empire, so unremitting was the tide of business, so deep was his need for control that there simply was not time for rest. All this he explained to his subjects in the laws that poured forth constantly from his government — as many as five in a single day; long, complex and involved texts in which the emperor took a close personal interest.

The pace of work for those who served Justinian must have been punishing, and it is perhaps unsurprising that he found few admirers amongst his civil servants. They traded dark hints about the hidden wellsprings of the emperor’s energy. One who had been with him late at night swore that as the emperor paced up and down, his head had seemed to vanish from his body. Another was convinced that Justinian’s face had become a mass of shapeless flesh, devoid of features. That was no human emperor in the palace on the banks of the Bosphorus, but a demon in purple and gold.

There is something uncanny about the story of Justinian, ruler of the eastern Roman Empire from 527 to 565. Born into rural poverty in the Balkans in the late 5th century, he came to prominence through the influence of his uncle Justin. A country boy made good as a guards officer, he became emperor almost by accident in 518. Justinian soon became the mainstay of the new regime and, when Justin died in 527, he was his obvious and preordained successor. The new emperor immediately showed his characteristically frenetic pace of activity, working in consort with his wife Theodora, a former actress of controversial reputation but real ability.

A flurry of diplomatic and military action put the empire’s neighbours on notice, whilst at home there was a barrage of reforming legislation. More ambitious than this, the emperor set out to codify not only the vast mass of Roman law, but also the hitherto utterly untamed opinions of Roman jurists — endeavours completed in implausibly little time that still undergird the legal systems of much of the world.

All the while, Justinian worked ceaselessly to bring unity to a Church fissured by deep theological divisions. After getting the best of Persia — Rome’s great rival — in a limited war on the eastern frontier, Justinian shrewdly signed an “endless peace” with the Sasanian emperor Khusro II in 532. The price — gold, in quantity — was steep, but worthwhile because it freed up resources and attention for more profitable ventures elsewhere.

In that same year, what was either a bout of serious urban disorder that became an attempted coup, or an attempted coup that led to rioting, came within an ace of overthrowing Justinian and levelled much of Constantinople. Other emperors might have been somewhat put off their stride, but not Justinian. The reform programme was intensified, with a severe crackdown on corruption and a wholesale attempt to rewire the machinery of government.

Constantinople was rebuilt on a grander scale, the church of Hagia Sophia being the most spectacular addition, a building that seems still to almost defy the laws of physics. At the same time, Justinian dispatched armies to recover regions lost to barbarian rulers as the western Roman Empire collapsed in the course of the 5th century. In brilliant and daring campaigns, the great general Belisarius conquered first the Vandal kingdom in North Africa (533–34) and then the much more formidable Ostrogothic realm in Italy (535–40), with armies that must have seemed almost insultingly small to the defeated.

If Justinian had had the good fortune to die in 540, he would have been remembered as the greatest of all Rome’s many emperors. Unfortunately for him, he lived. The 540s was a low, depressing decade for the Roman Empire. Khusro broke the endless peace, and a Persian army sacked the city of Antioch. The swift victories in the west collapsed into difficult wars of pacification, which at points the Romans seemed destined to lose.

December 30, 2023

Building the Walls of Constantinople

toldinstone

Published 15 Sept 2023This video, shot on location in Istanbul, explores the walls of Byzantine Constantinople — and describes how they finally fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

(more…)

December 26, 2023

The awe-inducing power of volcanoes

Ed West considers just how much human history has been shaped by vulcanology, including one near-extinction event for the human race:

A huge volcano has erupted in Iceland and it looks fairly awesome, both in the traditional and American teenager senses of the word.

Many will remember their holidays being ruined 13 years ago by the explosion of another Icelandic volcano with the epic Norse name Eyjafjallajökull. While this one will apparently not be so disruptive, volcano eruptions are an under-appreciated factor in human history and their indirect consequences are often huge.

Around 75,000 years ago an eruption on Toba was so catastrophic as to reduce the global human population to just 4,000, with 500 women of childbearing age, according to Niall Ferguson. Kyle Harper put the number at 10,000, following an event that brought a “millennium of winter” and a bottleneck in the human population.

In his brilliant but rather depressing The Fate of Rome, Harper looked at the role of volcanoes in hastening the end of antiquity, reflecting that “With good reason, the ancients revered the fearsome goddess Fortuna, out of a sense that the sovereign powers of this world were ultimately capricious”.

Rome’s peak coincided with a period of especially clement climatic conditions in the Mediterranean, in part because of the lack of volcanic activity. Of the 20 largest volcanic eruptions of the last 2,500 years, “none fall between the death of Julius Caesar and the year AD 169”, although the most famous, the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, did. (Even today it continues to reveal knowledge about the ancient world, including a potential treasure of information.)

However, the later years of Antiquity were marked by “a spasm” of eruptions and as Harper wrote, “The AD 530s and 540s stand out against the entire late Holocene as a moment of unparalleled volcanic violence”.

In the Chinese chronicle Nan Shi (“The History of the Southern Dynasties”) it was reported in February 535 that “there twice was the sound of thunder” heard. Most likely this was a gigantic volcanic explosion in the faraway South Pacific, an event which had an immense impact around the world.

Vast numbers died following the volcanic winter that followed, with the year 536 the coldest of the last two millennia. Average summer temperature in Europe fell by 2.5 degrees, and the decade that followed was intensely cold, with the period of frigid weather lasting until the 680s.

The Byzantine historian Procopius wrote how “during the whole year the sun gave forth its light without brightness … It seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear”. Statesman Flavius Cassiodorus wrote how: “We marvel to see now shadow on our bodies at noon, to feel the mighty vigour of the sun’s heat wasted into feebleness”.

A second great volcanic eruption followed in 540 and (perhaps) a third in 547. This led to famine in Europe and China, the possible destruction of a city in Central America, and the migration of Mongolian tribes west. Then, just to top off what was already turning out to be a bad decade, the bubonic plague arrived, hitting Constantinople in 542, spreading west and reaching Britain by 544.

Combined with the Justinian Plague, the long winter hugely weakened the eastern Roman Empire, the combination of climatic disaster and plague leading to a spiritual and demographic crisis that paved the way for the rise of Islam. In the west the results were catastrophic, and urban centres vanished across the once heavily settled region of southern Gaul. Like in the Near East, the fall of civilisation opened the way for former barbarians to build anew, and “in the Frankish north, the seeds of a medieval order germinated. It was here that a new civilization started to grow, one not haunted by the incubus of plague”.

October 2, 2023

The fall and rise of siege warfare

Sieges are probably about a year or so younger than the first fortified village — as soon as someone came up with the bright idea of throwing a wall around it for protection, some equally bright spark likely started coming up with ways to get inside that wall. In The Critic, Peter Caddick-Adams considers the eclipse and return of siege warfare in Europe in reviewing Iain MacGregor’s The Lighthouse of Stalingrad and Prit Buttar’s To Besiege a City: Leningrad 1941-42:

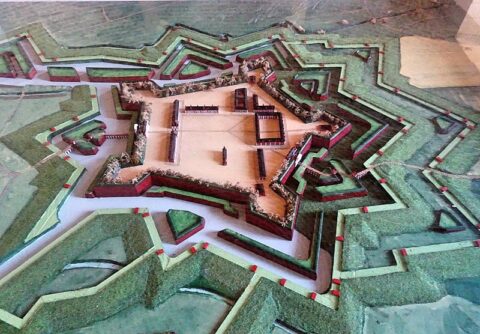

A model of the Vauban fortress at Arras in northern France. Arras is one of the Fortifications of Vauban, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The history of war is never far removed from battles for cities. Many of us, of whatever creed, were brought up on the story of the walls of Jericho tumbling after the Israelites marched around the stronghold once a day for six days, seven times on the seventh day, and then blew their trumpets. Though no archaeological evidence at Tell es-Sultan, in modern Palestine, corroborates the arresting visual image related in Joshua, Chapter 6, diggers have uncovered a range of defensive stone and brick walls dating back to 8,000 BC. It indicates that even 10,000 years ago, the ancients indulged in the odd siege when the mood took them. The biblical story also introduces us to the concept of intimidation, today fashionably called “psychological warfare”.

The much younger fortress of Troy provides insights into another city-focussed era of battles. Beneath today’s Hisarlik in northern Turkey are nine archaeological layers. Troy VIII was the alluring city of Classical and Hellenistic times, as portrayed in the Iliad, Homer’s Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid. The Romans took the lessons of Homeric Troy seriously and clad all their major settlements with defensive walls, as any exploration of Canterbury, Chester or York will confirm. These acted as magnets for opponents, as in Boudicca’s revolt of AD 60–61. Cities such as Colchester, London and St Albans were sacked, as much for what they represented as for their physical presence.

When the Normans arrived in their longships, they imported the concept of stone castles to control the newly conquered English. Their walled cities would be ungraded and contested scores of times over the succeeding six centuries. Henry V’s siege of Harfleur (modern Le Havre) in 1415, the beginning of the Agincourt campaign famously depicted in Shakespeare’s play, underlined the drawback of traditional sieges. They took longer and were usually far costlier than expected. Several thousand men camped in a small area with no knowledge of hygiene inevitably resulted in a high mortality rate amongst the attackers before a shot was fired.

Harfleur was also the first time an English army made use of gunpowder artillery in a siege, a technology that had trickled its way across the world from China. Powder and fuse heralded events 38 years later, when an Ottoman army shook the Christian world to its core by breaching the massive walls of Constantinople (Istanbul) after a 53-day bombardment using cannons. On Tuesday, 29 May 1453, stone finally gave way to bronze and iron, finishing the last remnant of the Roman Empire. Europe was never quite the same again. Fortress architecture started to employ breadth, using earthen ramparts and ditches, rather than height.

Strategy for urban warfare intensified during the lifetime of the French fortress engineer Vauban (1633–1707), who used landscaped terrain as well as geometrically designed defensive walls to deter would-be besiegers. When viewed from above, his fortification designs resemble starfish. So successful were his tactics that sieges, always costly and time-consuming, lessened in importance. His contemporary Marlborough recognised that on any cost-benefit analysis, Vauban had rendered sieges militarily unprofitable, restoring manoeuvre to campaigns.

Subsequent wars fought in the Napoleonic era, the Crimea, between the American North and South, and by Prussia generally reflected this return to mobility. There was the odd attritional discrepancy with the 1854–55 siege of Sevastopol, that of Petersburg in 1864–65 and Paris in 1870–71. Cities were still fought for, but usually contests were removed away from the walls, where forces could conduct wide sweeping manoeuvres, such as Leipzig in 1813 or Ypres in the Great War. As weapons grew more accurate and their munitions heavier, fortifications broadened and sank into the ground, culminating in the trenches of 1914–18. In this era, dominance of terrain became the hallmark, and it was virtually siege-free.

It was remarkable that urban warfare returned on an industrial scale during the Second World War, a time usually associated with blitzkrieg and rapid tank thrusts. This happened at Leningrad, Sevastopol and Stalingrad in the East; at Ortona and Cassino in Italy, Caen; Carentan and St Lo in Normandy; in Aachen and later assaults on Aschaffenburg and Cologne, Magdeburg, Leipzig and Berlin in 1945. Subsequent NATO doctrine for the defence of central Europe focussed on the threat of more attrition. Plans were devised to defend quite small localities, putting grit in the Soviet steamroller and making the cost of attacking Western towns and cities prohibitive.

Update: Broken URL corrected.

January 24, 2023

The Byzantine Empire: Part 9 – The Last Centuries

seangabb

Published 30 Dec 2022In this, the ninth in the series, Sean Gabb gives an overview of the last years of Byzantium, from the Crusader sack in 1204 to the Turkish capture in 1453.

Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or the Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

(more…)

December 8, 2022

Byzantine Honey Fritters

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 26 Jul 2022

(more…)

November 5, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 8 – The Breakdown, 1025-1204

seangabb

Published 20 May 2022In this, the eighth video in the series, Sean Gabb explains how, having acquired the wrong sort of ruling class, the Byzantine Empire passed in just under half a century from the hegemonic power of the Near East to a declining hulk, fought over by Turks and Crusaders.

Subjects covered include:

The damage caused by a landed nobility

The deadweight cost of uncontrolled bureaucracy

The first rise of an insatiable and all-conquering West

The failure of the Andronicus Reaction

The sack of Constantinople in 1204Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

October 28, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 7 – Recovery and Return to Hegemony, 717-1025 AD

seangabb

Published 2 May 2022In this, the seventh video in the series, Sean Gabb explains how, following the disaster of the seventh century, the Byzantine Empire not only survived, but even recovered its old position as hegemonic power in the Eastern Mediterranean. It also supervised a missionary outreach that spread Orthodox Christianity and civilisation to within reach of the Arctic Circle.

Subjects covered:

The legitimacy of the words “Byzantine” and “Byzantium”

The reign of the Empress Irene and its central importance to recovery

The recovery of the West and the Rise of the Franks

Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire

The Conversion of the Russians – St Vladimir or Vladimir the Damned?

The reign of Basil IIBetween 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

(more…)

October 25, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 6 – Weathering the Storm, 628-717 AD

seangabb

Published 16 Feb 2022In this, the sixth video in the series, Sean Gabb discusses the impact on the Byzantine Empire of the Islamic expansion of the seventh century. It begins with an overview of the Empire at the end of the great war with Persia, passes through the first use of Greek Fire, and ends with a consideration of the radically different Byzantine Empire of the Middle Ages.

Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or the Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

October 18, 2022

The War That Ended the Ancient World

toldinstone

Published 10 Jun 2022In the early seventh century, a generation-long war exhausted and virtually destroyed the Roman Empire. This video explores that conflict through the lens of an Armenian cathedral built to celebrate the Roman victory.

(more…)

October 8, 2022

Prelude to WW1 – The Balkan Wars 1912-1913

The Great War

Published 7 Oct 2022The Balkan Wars marked the end of Ottoman rule in Southeastern Europe, and they involved several countries that would join the First World War just a few years later. A complicated alliance between Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria and Greece imploded over disagreement of the war spoils after defeating the Ottomans. This led to the 2nd Balkan War and also created much resentment that would play a role between 1914 and 1918 too.

(more…)

September 29, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 5 – The Death of Roman Byzantium, 568-628 AD

seangabb

Published 21 Jan 2022In this, the fifth lecture in the series, Sean Gabb discusses the progressive collapse of Byzantium between the middle years of Justinian and the unexpected but sterile victory over the Persian Empire.

Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or the Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

September 20, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 4 – Justinian, The Hand of God

seangabb

Published 1 Jan 2022Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

September 16, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 3 – The Age of Justinian – Cashing in the Gains of the Fifth Century

seangabb

Published 7 Dec 2022Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or the Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)