The Line

Published Apr 16, 2024General Wayne Eyre served for decades in the Canadian Army, including as its commander, before being promoted to Chief of the Defence Staff in 2021. During his time as Canada’s top soldier, he has overseen not only a series of challenges inside the Canadian military, but also a rapid deterioration in the geopolitical environment. The world is a more dangerous place, and Gen. Eyre has been unusually outspoken in noting that Canada needs to do more to be ready for what’s coming.

In this conversation with The Line‘s Matt Gurney, the general provides his take on the state of the world today, shares his thoughts on the recently announced Defence Policy Update, and talks about why he is encouraged by some of what he is already seeing change with Canada’s military readiness.

On The Line is The Line‘s newest podcast, featuring longer interviews by either Jen or Matt with someone who is currently in the news or able to speak to something topical (or, sometimes, simply fun and interesting). We are still getting it up to speed, but Line listeners and viewers can expect an episode weekly by next month, at the latest.

To never miss an episode of either On The Line or The Line Podcast, sign up today to follow us on YouTube, on the streaming app of your choice and, of course, at ReadtheLine.ca, home of The Line. Like and subscribe!

Please note: This interview was recorded on Friday, before the Iranian attack on Israel.

April 18, 2024

On The Line with General Wayne Eyre, commander of the Canadian Armed Forces

April 14, 2024

QotD: Imperium in the Roman Republic

What connects these offices in particular is that they confer imperium, a distinctive concept in Roman law and governance. The word imperium derives from the verb impero, “to command, order” and so in a sense imperium simply means “command”, but in its implication it is broader. Imperium was understood to be the power of the king (Cic. Leg. 3.8), encompassing both the judicial role of the king in resolving disputes and the military role of the king in leading the army. In this sense, imperium is the power to deploy violence on behalf of the community: both internal (judicial) violence and external (military) violence.

That power was represented visually around the person of magistrates with imperium through the lictors (Latin: lictores), attendants who follows magistrates with imperium, mostly to add dignity to the office but who also could act as the magistrate’s “muscle” if necessary. The lictors carried the fasces, a set of sticks bundled together in a rod; often in modern depictions the bundle is thick and short but in ancient artwork it is long and thin, the ancient equivalent of a policeman’s less-lethal billy club. That, notionally non-lethal but still violent, configuration represented the imperium-bearing magistrate’s civil power within the pomerium (recall, this is the sacred boundary of the city). When passing beyond the pomerium, an axe was inserted into the bundle, turning the non-lethal crowd-control device into a lethal weapon, reflective of the greater power of the imperium-bearing magistrate to act with unilateral military violence outside of Rome (though to be clear the consul couldn’t just murder you because you were on your farm; this is symbolism). The consuls were each assigned 12 lictors, while praetors got six. Pro-magistrates [proconsuls and propraetors] had one fewer lictor than their magistrate versions to reflect that, while they wielded imperium, it was of an inferior sort to the actual magistrate of the year.

What is notable about the Roman concept of imperium is that it is a single, unitary thing: multiple magistrates can have imperium, you can have greater or lesser forms of imperium, but you cannot break apart the component elements of imperium.1 This is a real difference from the polis, where the standard structure was to take the three components of royal power (religious, judicial and military) and split them up between different magistrates or boards in order to avoid any one figure being too powerful. For the Romans, the royal authority over judicial and military matters were unavoidably linked because they were the same thing, imperium, and so could not be separated. That in turn leads to Polybius’ awe at the power wielded by Roman magistrates, particularly the consuls (Polyb. 6.12); a polis wouldn’t generally focus so much power into a single set of hands constitutionally (keeping in mind that tyrants are extra-constitutional figures).

So what does imperium empower a magistrate to do? All magistrates have potestas, the power to act on behalf of the community within their sphere of influence. Imperium is the subset of magisterial potestas which covers the provision of violence for the community and it comes in two forms: the power to raise and lead armies and the power to organize and oversee courts. Now we normally think of these powers as cut by that domi et militiae (“at home and on military service”) distinction we discussed earlier in the series: at home imperium is the power to organize courts (which are generally jury courts, though for some matters magistrates might make a summary judgement) and abroad the power to organize armies. But as we’ll see when we get to the role of magistrates and pro-magistrates in the provinces, the power of legal judgement conferred by imperium is, if anything, more intense outside of Rome. That said it is absolutely the case that imperium is restrained within the pomerium and far less restrained outside of it.

There were limits on the ability of a magistrate with imperium to deploy violence within the pomerium against citizens. The Lex Valeria, dating to the very beginning of the res publica stipulated that in the case of certain punishments (death or flogging), the victim had the right of provocatio to call upon the judgement of the Roman people, through either an assembly or a jury trial. That limit to the consul’s ability to use violence was reinforced by the leges Porciae (passed in the 190s and 180s), which protected civilian citizens from summary violence from magistrates, even when outside of Rome. That said, on campaign – that is, militae rather than domi – these laws did not exempt citizen soldiers from beating or even execution as a part of military discipline and indeed Roman military discipline struck Polybius – himself an experienced Greek military man – as harsh (Polyb. 6.35-39).

In practice then, the ability of a magistrate to utilize imperium within Rome was hemmed in by the laws, whereas when out in the provinces on campaign it was far less limited. A second power, coercitio or “coercion” – the power of a higher magistrate to use minor punishments or force to protect public order – is sometimes presented as a distinct power of the magistrates, but I tend to agree with Lintott (op. cit., 97-8) that this rather overrates the importance of the coercive powers of magistrates within the pomerium; in any case, the day-to-day maintenance of public order generally fell to minor magistrates.

While imperium was a “complete package” as it were, the Romans clearly understood certain figures as having an imperium that outranked others, thus dictators could order consuls, who could order praetors, the hierarchy neatly visualized by the number of lictors each had. This could create problems, of course, when Rome’s informal systems of hierarchy conflicted with this formal system, for instance at the Battle of Arausio, the proconsul Quintus Servilius Caepio refused to take orders from the consul, Gnaeus Mallius Maximus, because the latter was his social inferior (being a novus homo, a “new man” from a family that hadn’t yet been in the Senate and thus not a member of the nobiles), despite the fact that by law the imperium of a sitting consul outranked that of a pro-consul. The result of that bit of insubordination was a military catastrophe that got both commanders later charged and exiled.

Finally, a vocabulary note: it would be reasonable to assume that the Latin word for a person with imperium would be imperator2 because that’s the standard way Latin words form. And I will say, from the perspective of a person who has to decide at the beginning of each thing I write what circumlocution I am going to use to describe “magistrate or pro-magistrate with imperium“, it would be remarkably fortunate if imperator meant that, but it doesn’t. Instead, imperator in Latin ends up swallowed by its idiomatic meaning of “victorious general”, as it was normal in the republic for armies to proclaim their general as imperator after a major victory (which set the general up to request a triumph from the Senate). In the imperial period, this leads to the emperors monopolizing the term, as all of the armies of Rome operated under their imperium and thus all victory accolades belonged to the emperor. That in turn leads to imperator becoming part of the imperial title, from where it gives us our word “emperor”.

That said, the circumlocution I am going to use here, because this isn’t a formal genre and I can, is “imperium-haver”. I desperately wish I could use that in peer reviewed articles, but I fear no editor would let me (while Reviewer 2 will predictably object to “general”, “commander” or “governor” for all being modern coinages).3

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How to Roman Republic 101, Part IIIb: Imperium”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-08-18.

1. I should note here that Drogula (in Commanders and Command (2015)) understands imperium a bit differently than this more traditional version I am presenting (in line with Lintott’s understanding). He contends that imperium was an entirely military power which was not necessary for judicial functions and was not only indivisible but also, at least early on, did not come in different degrees. In practice, I’m not sure the Romans were ever so precise with their concepts as Drogula wants them to be.

2. Pronunication note because this bothers me when I hear this word in popular media: it is not imPERator, but impeRAtor, because that “a” is long by nature, and thus keeps the stress.

3. And yes, really, I have had reviewers object to “general” or “commander” to mean “the magistrate or pro-magistrate with imperium in the province”. There is no pleasing Reviewer 2.

March 23, 2024

Ireland’s Varadkar heads for the showers

In Spiked, Brendan O’Neill discusses the “shocking” — but not actually shocking — resignation of Ireland’s Taoiseach (prime minister):

“I am no longer best man to be Irish PM”, said a BBC headline this week, summarising Leo Varadkar’s resignation speech. The truth, Leo, is that you were never the best man to be Irish PM. He was never elected by the people to be taoiseach, instead securing that seat of power by appointment and backroom dealing. And once there, once he’d been gifted the highest office in the land by his allies in Dublin 4, he wielded government not for the people, but against them. He bent Ireland to what was essentially a vast real-time experiment in social re-engineering and thought control.

An unelected ruler using his power and clout to correct the country and improve the people? There’s a word for that. And it isn’t “democracy”.

Varadkar announced his resignation on Wednesday. In an emotional speech he said he was stepping down as leader of Fine Gael immediately and will step down as taoiseach once his successor has been chosen. His “shock departure” followed the people’s crushing defeat of the twin referendum he put forward. Overwhelming majorities rejected his proposals to alter the Irish constitution to update its definition of “family” and to fix what Varadkar damned as its “very sexist” reference to a woman’s “duties” in the home. No thanks, said the electorate, in the biggest ever referendum loss by an Irish government.

Even the fact that Varadkar’s stepping down is widely seen as a “shock move” speaks to the haughtiness, the outright unworldliness, of his political kind. To many of us it makes perfect sense that a PM would bugger off after suffering a historically unprecedented bloody nose from voters. But it seems the Varadkar clique thought they could ride it out. “No biggie” was their view. Until his “shock departure” on Wednesday, reports the Guardian, “the political fallout from the [referendum] debacle had widely been expected to be limited”.

Who expected that? I’m sure those voters who gleefully seized the opportunity of the referendum to give the middle finger to Varadkar and the rest of the establishment didn’t expect the impact of their discontent to be “limited”. It is a testament to the arrogance of technocracy, to the chasm that has emerged between Ireland’s rulers and Ireland’s ruled, that the Dublin establishment thought it could shrug off the largest drubbing it has ever received from voters.

In the end, tellingly, it seems it was disgruntlement from within his own party ranks, rather than the disgruntlement of the oiks, that convinced Varadkar to go. He was facing “increasing discontent within Fine Gael”, with some party bigwigs worried he’s an “electoral liability”. Everything you need to know about the man is contained in the fact that he essentially shrugged when the masses rose up against him but bolted when his fellow clerisy members criticised him. To the technocrat, the disapproval of their dinner-party circle carries far more weight than the discontent of ordinary people.

If Varadkar was edged out by the tut-tutting of movers and shakers, it would be a fitting end to a career that always owed more to the intrigue of political insiders than to the enthusiasm of the electorate. It is an unremarked upon truth that Varadkar was never installed into power by the people. He first became taoiseach in 2017 when then taoiseach Enda Kenny resigned as leader of Fine Gael. Varadkar was elected new party leader and became taoiseach on the back of it. So he became PM of Ireland on the back of the deliberations of 25,000 party members, not the ballots of the people.

Actually, even members of Fine Gael weren’t especially enthused by him. Varadkar’s opponent in the 2017 leadership contest – Simon Coveney – won almost twice as many votes from party members: 7,051 to Varadkar’s 3,772. But Varadkar won more votes from members of the parliamentary party – 51 to Coveney’s 22 – which meant Fine Gael’s weighted electoral college ruled in his favour rather than Coveney’s. From the get-go, Varadkar’s rule of Ireland was more an accomplishment of elite patronage than democratic keenness.

March 7, 2024

QotD: Helmuth von Moltke’s Kabinettskriege of 1870

[The Franco-Prussian War] is generally considered the magnum opus of the titanic Prussian commander, Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke. Exercising deft operational control and an uncanny sense of intuition, Moltke orchestrated an aggressive opening campaign which sent Prusso-German armies streaming like a mass of tentacles into France, trapping the primary French field army in the fortress of Metz in the opening weeks of the war and besieging it. When the French Emperor, Napoleon III, marched out with a relief army (comprising the rest of France’s battle-worthy formations), Moltke hunted that army down as well, encircling it at Sedan and taking the entire force (and the emperor) into captivity.

From an operational perspective, this sequence of events was (and is) considered a masterclass, and a major reason why Moltke has become revered as one of history’s truly great talents (he is on this writer’s Mount Rushmore alongside Hannibal, Napoleon, and Manstein). The Prussians had executed their platonic ideal of warfare — the encirclement of the main enemy body — not once, but twice in a matter of weeks. In the conventional narrative, these great encirclements became the archetype of the German kesselschlacht, or encirclement battle, which became the ultimate goal of all operations. In a certain sense, the German military establishment spent the next half-century dreaming of ways to replicate its victory at Sedan.

This story is true, to a certain extent. My objective here is not to “bust myths” about blitzkrieg or any such trite thing. However, not everyone in the German military establishment looked at the Franco-Prussian War as an ideal. Many were terrified by what happened after Sedan.

By all rights, Moltke’s masterpiece at Sedan should have ended the war. The French had lost both of their trained field armies and their head of state, and ought to have given in to Prussia’s demand (namely, the annexation of the Alsace-Lorraine region).

Instead, Napoleon III’s government was overthrown and a National Government was declared in Paris, which promptly declared what amounted to a total war. The new government abandoned Paris, declared a Levee en Masse — a callback to the wars of the French Revolution in which all men aged 21 to 40 were to be called to arms. Regional governments ordered the destruction of bridges, roads, railways, and telegraphs to deny their use to the Prussians.

Instead of bringing France to its knees, the Prussians found a rapidly mobilizing nation which was determined to fight to the death. The mobilization prowess of the emergency French government was astonishing: by February, 1871, they had raised and armed more than 900,000 men.

Fortunately for the Prussians, this never became a genuine military emergency. The newly raised French units suffered from poor equipment and poor training (particularly because most of France’s trained officers had been captured in the opening campaign). The new mass French armies had poor combat effectiveness, and Moltke managed to coordinate the capture of Paris alongside a campaign which saw Prussian forces marching all over France to run down and destroy the elements of the new French Army.

Big Serge, “The End of Cabinet War”, Big Serge Thought, 2023-11-30.

February 28, 2024

Why Germany Lost the First World War

The Great War

Published Nov 10, 2023Germany’s defeat in the First World War has been blamed on all kinds of factors or has even been denied outright as part of the “stab in the back” myth. But why did Germany actually lose?

(more…)

February 10, 2024

“Ukraine is running out of soldiers to man the front”

In the second part of his review of the situation in the Russo-Ukrainian War, Niccolo Soldo discusses why the plight of Ukraine’s military is getting worse, not better:

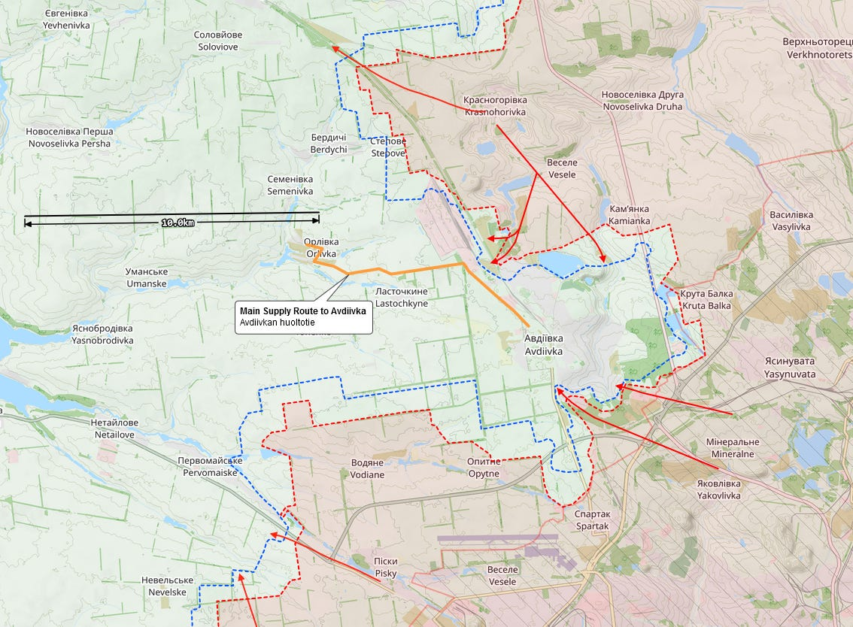

Since the previous entry was published, several key developments continue to make the outlook for Ukraine even gloomier than it already was then. The Ukrainian-held city of Avdiivka is now falling to Russian forces. This city is right next to Donetsk, the largest city in the Donbass. It is from Avdiivka that the Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF) have been shelling that city for almost a decade now. It is considered by many to be the location with the strongest fortifications along the entire front line. Its capture by the Russians would be a significant victory, not just because of the size of the battle, but especially because it would spare the city of Donetsk from any future artillery barrages from the Ukrainian side.

Since the last entry, the ongoing fight between President Zelensky and his top general, Valeri Zaluzhny, has broken out into the open. Zelensky has indicated that he will be replacing Zaluzhny (and others) in order to “shake up” Ukraine’s war effort, a move that the general refuses to accept. The two Z’s do not see eye-to-eye, with observers informing us that Zaluzhny has called for the UAF to pull out of Avdiivka in order to buy time and not lose more men and arms in defending a city that they would lose in due time. [NR: Zelensky announced that Oleksandr Syrsky has replaced Zaluzhny on February 9th.]

Making matters even worse for the Ukrainians, the US Senate failed to agree to send more money to Kiev to help them in their fight against the Russians. Ukrainian officials told the Guardian that the failure in the US Senate “… will have real consequences in terms of lives on the battlefield and Kyiv’s ability to hold off Russian forces on the frontline”. US Aid For Ukraine President Yuriy Boyechko sounded an even gloomier note:

Everyone was hoping that US won’t let us down, and now we find ourselves at a very difficult place. People are losing hope little by little. We don’t have time for this because we see what’s going on at the front. The more time we give for the Russians to build up their stockpiles, even if the aid is going to show up it might be too little too late.

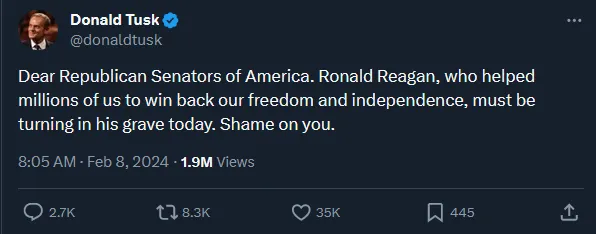

Newly-elected Polish Premier Donald Tusk criticized Senate Republicans by invoking the memory of Ronald Reagan:

And not to be outdone, Politico is blaming who else but Donald Trump.

The EU did finally manage to convince Hungary to agree to a new 50 Billion EUR package for Ukraine, but European leaders all agree that it is “nowhere near enough”, and requires the USA to chip in just as much as a minimum to sustain the war effort. This package is to be spread out until 2027, but Ukraine faces a funding shortfall of 40 Billion USD this year alone! From the linked article:

“Everyone realizes that €50 billion is not enough,” said Johan Van Overtveldt, a Belgian conservative who chairs the European Parliament’s Budget Committee. “Europe realizes that it needs to step up its efforts.” And by that, he means finding money from elsewhere.

World Bank estimates put Ukraine’s long-term needs for reconstruction at $411 billion.

Money is one thing (and a very, very important thing at that), but all the money in the world doesn’t address the elephant in the room: Ukraine is running out of soldiers to man the front.

Napoleon’s Revenge: Wagram 1809

Epic History TV

Published Jun 21, 2019Six weeks after his bloody repulse at the Battle of Aspern-Essling, Napoleon led his reinforced army back across the Danube. The resulting clash with Archduke Charles’s Austrian army was the biggest and bloodiest battle yet seen in European history, and despite heavy French losses, resulted in a decisive strategic victory for the French Emperor.

(more…)

January 7, 2024

QotD: The US Army between 1945 and 1950

One aftermath of the Korean War has been the passionate attempt in some military quarters to prove the softness and decadence of American society as a whole, because in the first six months of that war there were wholesale failures. It has been a pervasive and persuasive argument, and it has raised its own counterargument, equally passionate.

The trouble is, different men live by different myths.

There are men who would have a society pointed wholly to fighting and resistance to Communism, and this would be a very different society from the one Americans now enjoy. It might succeed on the battlefield, but its other failures can be predicted.

But the infantry battlefield also cannot be remade to the order of the prevailing midcentury opinion of American sociologists.

The recommendations of the so-called Doolittle Board of 1945-1946, which destroyed so much of the will — if not the actual power — of the military traditionalists, and left them bitter, and confused as to how to act, was based on experience in World War II. In that war, as in all others, millions of civilians were fitted arbitrarily into a military pattern already centuries old. It had once fitted Western society; it now coincided with American customs and thinking no longer.

What the Doolittle Board tried to do, in small measure, was to bring the professional Army back into the new society. What it could not do, in 1946, was to gauge the future.

By 1947 the United States Army had returned, in large measure, to the pattern it had known prior to 1939. The new teen-agers who now joined it were much the same stripe of men who had joined in the old days. They were not intellectuals, they were not completely fired with patriotism, or motivated by the draft; nor was an aroused public, eager to win a war, breathing down their necks.

A great many of them signed up for three squares and a sack.

Over several thousand years of history, man has found a way to make soldiers out of this kind of man, as he comes, basically unformed, to the colors. It is a way with great stresses and great strains. It cannot be said it is wholly good. Regimentation is not good, completely, for any man.

But no successful army has been able to avoid it. It is an unpleasant necessity, seemingly likely to go on forever, as long as men fight in fields and mud.

One thing should be made clear.

The Army could have fought World War III, just as it could have fought World War II, under the new rules. During 1941-1945 the average age of the United States soldier was in the late twenties, and the ranks were seasoned with maturity from every rank of life, as well as intelligence.

In World War III, or any war with national emotional support, this would have again been true. Soldiers would have brought their motivation with them, firmed by understanding and maturity.

The Army could have fought World War III in 1950, but it could not fight Korea.

T.R. Fehrenbach, This Kind of War: A Study in Unpreparedness, 1963.

December 29, 2023

The Soviet follow-on operation after Bagration

Big Serge discusses the state of the Germans on the Eastern Front at the end of the massive Soviet attacks that collapsed Army Group Centre in 1944:

But now, as Bagration began to run out of momentum, the Soviets really did put Model’s army group in the crosshairs with an enormous follow up offensive — the second phase of their summer blockbuster. Model’s army group consisted of two Panzer Armies (the 4th and 1st), and an allied Hungarian force guarding the southern flank. On paper, a pair of Panzer Armies was a formidable force, but like all German units at this stage in the war they were understrength, and by this point they were already bleeding strength as panzer divisions were scrambled north to try and slow down Operation Bagration.

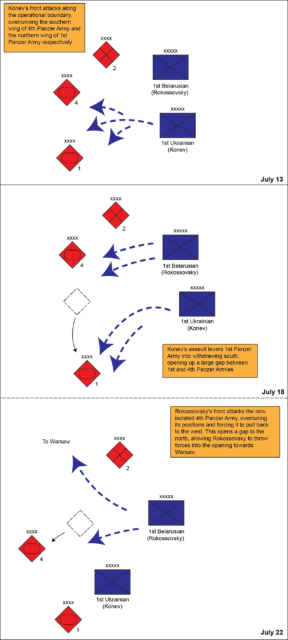

Arrayed against Model’s force were two Soviet Fronts (the equivalent of an Army Group) under a pair of the Red Army’s best operators. The lead off assault came on July 13, with Marshal Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front forcing positions in the interstitial zone between Model’s two Panzer Armies. Konev’s intention was to split the two armies apart, force a penetration between them, and then curl into the rear to encircle one, or if possible both of them. Therefore, Konev’s initial assault was highly concentrated, with as much as 70 percent of his artillery and 90 percent of his armor assembled in a few narrow sectors selected for breaching.

With this level of force concentration by the attackers, there was really little that the Germans could do. Nevertheless, a somewhat lethargic and stiff German response helped make the disaster even worse. 4th Panzer Army headquarters initially believed Konev’s opening assault to be only a local attack – later defensively arguing that “there were as yet no signs of the attack being extended to other sections of the front” — and so attempted to respond with local counterattacks by its own reserves. As a result, by the second day of the Soviet offensive the Panzer Army had already committed all of its organic reserves while failing to withdraw from defensive positions that were already compromised. By the time they realized that Konev was launching a serious offensive operation, it was too late. Konev had already bashed into critical seams in the German front, turning his forces into a giant splitting wedge, in place to pry the whole front open.

[…]

What the Soviets had achieved with their enormous assaults on Army Group North Ukraine was remarkable. By precisely targeting the seams in the German formations, the initial attacks had pried open the German position like a clam, forcing the two panzer armies to retreat in opposite directions — the 1st pulling back to the south towards Hungary, and the 4th withdrawing westward towards Krakow. These diverging withdrawals opened enormous voids in the German line — the official German history of the war simply refers to this sequence of events as “the loss of a continuous front”. In a war where the enemy wielded vast mechanized forces, such gaps were fatal.

Rokossovsky and Konev had essentially overrun an entire German army group — and the best equipped group in the east, at that — in the space of about ten days, wedging the German line open and creating vast voids to drive into. Most importantly, Rokossovsky now faced one of the more tantalizing opportunities of the entire war. A great space now beckoned him to drive north towards Warsaw, and in his path was only the tired remnant of German second army — a force with no armor whatsoever, caught completely out of position.

Any wargamer could look at the map as Rokossovsky saw it and see that the opportunity to win a seminal, world-historical victory was now within reach. A sharp drive on Warsaw would put him in position to not only capture the city (a major transportation, administrative, and supply base), but also smash through the threadbare German 2nd Army and drive to the Baltic Coast. If he could achieve this, fully half of the German eastern forces would be encircled — the entirety of Army Group North (still fighting on the Baltic Coast) and everything that remained of Army Group Center. Rokossovksy now saw little standing between his powerful Front and one of the greatest encirclements — perhaps the greatest — of all time. No less than six German armies were sitting, naked and vulnerable, on the proverbial silver platter.

The Eastern Front was on the verge of total collapse. If Rokossovsky could bash through Warsaw (a seemingly simple proposition, given the enormous overmatch that he enjoyed over German 2nd Army), he would wipe out half the German eastern army and face no meaningful German forces between him and Berlin.

December 28, 2023

War-winning expertise of 1918, completely forgotten by 1939

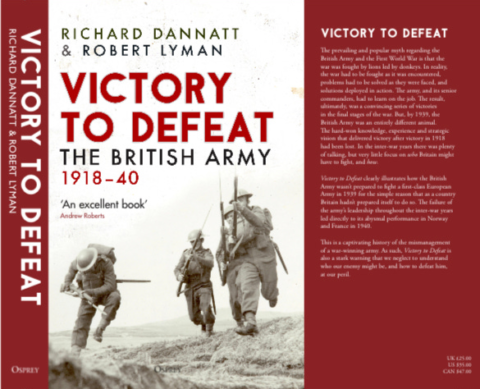

Dr. Robert Lyman writes about the shocking contrasts between the British Army (including the Canadian and Australian Corps) during the Hundred Days campaign of 1918 and the British Expeditionary Force that was driven from the continent at Dunkirk:

There was a fleeting moment during the One Hundred Days battles that ended the First World War in France in which successful all-arms manoeuvre by the British and Commonwealth armies, able to overturn the deadlock of previous years of trench stalemate, was glimpsed. But the moment, for the British Army at least, was not understood for what it was. With hindsight we can see that it was the birth of modern warfare, in which armour, infantry, artillery and air power are welded together able successfully to fight and win a campaign against a similarly-equipped enemy. Unfortunately in the intervening two decades the British Army simply forgot how to fight a peer adversary in intensive combat. It did not recognise 1918 for what it was; a defining moment in the development of warfare that needed capturing and translating into a doctrine on which the future of the British Army could be built. The tragedy of the inter-war years therefore was that much of what had been learned at such high cost in blood and treasure between 1914 and 1918 was simply forgotten. It provides a warning for our modern Army that once it goes, the ability to fight intensively at campaign level is incredibly hard to recover. The book that General Lord Dannatt and I have written traces the catastrophic loss of fighting knowledge after the end of the war, and explains the reasons for it. Knowledge so expensively learned vanished very quickly as the Army quickly adjusted back to its pre-war raison d’etre: imperial policing. Unsurprisingly, it was what many military men wanted: a return to the certainties of 1914. It was certainly what the government wanted: no more wartime extravagance of taxpayer’s scarce resources. The Great War was seen by nearly everyone to be a never-to-be-repeated aberration.

The British and Commonwealth armies were dramatically successful in 1918 and defeated the German Armies on the battlefield. Far from the “stab in the back” myth assiduously by the Nazis and others, the Allies fatally stabbed the German Army in the chest in 1918. The memoirs of those who experienced action are helpful in demonstrating just how far the British and Commonwealth armies had moved since the black days of 1 July 1916. The 27-year old Second Lieutenant Duff Cooper, of the 3rd Battalion The Grenadier Guards, waited with the men of 10 platoon at Saulty on the Somme for the opening phase of the advance to the much-vaunted Hindenburg Line. His diaries show that his experience was as far distant from those of the Somme in 1916 as night is from day. There is no sense in Cooper’s diaries that either he or his men felt anything but equal to the task. They were expecting a hard fight, but not a slaughter. Why? Because they had confidence in the training, their tactics of forward infiltration, their platoon weapons and a palpable sense that the army was operating as one. They were confident that their enemy could be beaten.

[…]

It would take the next war for dynamic warfare to be fully developed. It would be mastered in the first place by the losers in 1918 – the German Army. The moment the war ended the ideas and approaches that had been developed at great expense were discarded as irrelevant to the peace. They weren’t written down to be used as the basis for training the post-war army. Flanders was seen as a horrific aberration in the history of warfare, which no-right thinking individual would ever attempt to repeat. Combined with a sudden raft of new operational commitments – in the remnants of the Ottoman Empire, Russia and Ireland – the British Army quickly reverted to its pre-1914 role as imperial policemen. No attempt was made to capture the lessons of the First World War until 1932 and where warfighting was considered it tended to be about the role of the tank on the future battlefield. This debate took place in the public arena by advocates writing newspaper articles to advance their arguments. These ideas were half-heartedly taken up by the Army in the later half of the 1920s but quietly dropped in the early 1930s. The debates about the tank and the nature of future war were bizarrely not regarded as existential to the Army and they were left to die away on the periphery of military life.

The 1920s and 1903s were a low point in national considerations about the purpose of the British Army. The British Army quickly forgot what it had so painfully learnt and it was this, more than anything else, that led to a failure to appreciate what the Wehrmacht was doing in France in 1940 and North Africa in 1941-42.

November 16, 2023

QotD: Infantry soldiers in the age of pike and shot

The pike and the musket shifted the center of warfare away from aristocrats on horses towards aristocrats commanding large bodies of non-aristocratic infantry. But, as comes out quite clearly in their writing, those aristocrats were quite confident that the up-jumped peasants in their infantry lacked any in-born courage at all. Instead, they assumed (in their prejudice) that such soldiers would require relentless synchronized drilling in order to render the complex sequence of actions to reload a musket absolutely mechanical. As Lee points out [in Waging War], this training approach wasn’t necessary – other contemporary societies adapted to gunpowder just fine without it – but was a product of the values and prejudices of the European aristocracy of the 1500 and 1600s.

Such soldiers were, in their ideal, to quickly but mechanically reload their weapons, respond to orders and shift formation more or less oblivious to the battle around them. Indeed, uniforms for these soldiers came to favor high, starched collars precisely to limit their field of vision. This is not the man who, in Tyrtaeus’ words (elsewhere in his corpus), “bites on his lip and stands against the foe” but rather a human who, in the perfect form, was so mechanical in motions and habits that their courage or lack thereof, their awareness of the battlefield or lack thereof, didn’t matter at all. But at least, the [Classical] Greek might think, at least such men still ought not quail under fire but instead stood tall in the face of it.

After all, as late as the Second World War, it was thought that good British officers ought not duck or take cover under fire, in order to demonstrate and model good coolness under fire for their soldiers. The impression I get from talking to recent combat veterans (admittedly, American ones rather than British, since I live in the United States) is that an officer who behaved in that same way on today’s battlefield would be thought reckless (or stupid), not brave. Instead, the modern image of courage under fire is the soldier moving fast, staying low, moving to and through cover whenever possible – recklessness is discouraged precisely because it might put a comrade in danger.

Instead, the courage that is valued in many of today’s armies is the courage to stay calm and make cool, rational decisions. It is, to borrow the first line in Rudyard Kipling’s “If-“, “If you can keep your head when all about you/Are losing theirs and blaming it on you.” Which is not at all what was expected of the 17th century infantryman, whose officers trusted him to make nearly no decisions at all! But, as we’ve discussed, the modern system of combat demands that lots of decisions be devolved down further and further in the command hierarchy, with senior officers giving subordinates (often down to NCOs) the freedom to alter plans on the fly at the local level so long as they are following the general mission instructions (a system often referred to by its German term, auftragstaktik).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Universal Warrior, Part IIa: The Many Faces of Battle”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-02-05.

November 6, 2023

Justin Trudeau’s (latest) very bad week

Paul Wells wonders if Justin Trudeau would even want to stay on as Liberal Party leader for the next election after the more recent awful week he’s had:

That was fun of Justin Trudeau to act out the message that somebody who spends his days in the Senate is a nobody. Of course, the kind of year he’s having, his bit of theatre came two days after he appointed five new senators. Welcome to the upper chamber, suckers. If you’re really lucky, a flailing prime minister might use you for a punchline.

This felt like the week that Trudeau’s hold on his leadership became precarious. I’ve had people asking me all week whether Trudeau will run again. Of course I don’t know. I guess the only thing that’s new is that if he does stay until the next election, and lead the Liberals into it, I’ll wonder — more keenly than before — why he bothered.

The decision still feels like his alone. The headline-making assaults on his power this week fell well short of what it would take to remove him if he doesn’t want removing. I find Percy Downe a serious and likable man, but he is not gregarious, he doesn’t have networks of people ready to do his bidding, and the truth is that the Senate isn’t a base for getting anything done within the Liberal Party. Hasn’t been for a decade.

As a good Liberal who was working hard long before “hard work” became a Trudeauite slogan, Downe has never forgiven Trudeau for kicking senators out of the Liberal caucus. As a good Prince Edward Islander, he has never forgiven Trudeau for maintaining tolls on the Confederation Bridge between the Island and the mainland while removing tolls on the Champlain Bridge into Montreal. This was a straightforward transfer of wealth from PEI to Central Canada, and turned out to be foreshadowing for last week’s fuel-oil transfer in the other direction. So Downe has a grudge or two to motivate him, and no army to deliver his desired outcome. His preference for Trudeau’s political future is widely shared in the country but he lacks a mechanism for delivering it in real life.

At least Downe has been expressing a clear preference in coherent language. In this he contrasts nicely with Mark Carney. Carney was a successful central-bank governor in two countries, a feat without obvious precedent. But politics is a different line of work. Reading Carney’s interview with the Globe was like watching somebody shake a Ziploc bag full of fridge magnets. In fact I’m pretty sure that when he started talking, he wasn’t planning to deliver any message about party politics.

He’ll “lean in where I can”. He has a list of things he hasn’t ruled out: becoming the next Liberal leader; running for Parliament. Running for Parliament is also on his list of things he hasn’t ruled in. Not ruling things out is, notoriously, not how you actually get into Parliament. I haven’t ruled out becoming a backup dancer for Taylor Swift, and yet I’m not in the new concert film. I checked.

November 5, 2023

QotD: The Auftragstaktik principle of the Third Reich

[The Nazis], being Social Darwinists to the core, applied the military principle of Auftragstaktik to civilian life. “Mission-oriented” tactics means that the overall commanders leave as much as possible to the on-the-spot commanders, be they officers or noncoms, on the theory that properly-trained leaders will have a much better understanding of what needs to be done, and how to do it, than some general back at HQ. It’s the main reason the Wehrmacht could keep fighting so well, for so long, in the face of overwhelming opposition — tasks that would fall to an American company, or a Russian regiment, were often undertaken by a Wehrmacht platoon under the command of a senior corporal.

Obviously civilian life isn’t as goal-directed as the military in wartime, but a similar principle applied — given a vague set of generalized objectives from the top (Kershaw’s famous “working towards the Führer” thesis), everyone at every level was encouraged to move the ball downfield as he saw fit … with the added twist that, in the absence of a clearly defined, military-style chain of command, the various “subordinates” would ruthlessly battle it out with each other, Darwin-style, for bureaucratic supremacy.

Thus the Nazis’ infamous plate-of-spaghetti org charts. I’m not an expert, but I’m pretty sure there were more than a few guys who held wildly different ranks in various different organizations simultaneously. He might be a mere patrolman in the Order Police, but an officer in the SS, a noncom in the SA (you could be in both, at least in the early days), and so forth. I wouldn’t be surprised if there was more than one guy who technically reported to himself, somewhere deep in the bowels of the RHSA [Reich Security Main Office]. You could spend a lifetime trying to sort this stuff out …

Severian, “The Crisis of the Third Decade”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-03-18.

October 28, 2023

Smith versus Smith: US Army/Marine relations in 1944

World War Two

Published 27 Oct 2023When Marine Corps General Holland “Howling Mad” Smith removed Infantry General Ralph Smith from command in 1944 during the Battle of Saipan, it began a controversy that soon snowballed, threatening to sabotage Army-Marine relations at a time when cooperation was the key to victory.

(more…)

October 21, 2023

QotD: The US Army’s Korean War blooding

There is much to military training that seems childish, stultifying, and even brutal. But one essential part of breaking men into military life is the removal of misfits — and in the service a man is a misfit who cannot obey orders, any orders, and who cannot stand immense and searing mental and physical pressure.

For his own sake and for that of those around him, a man must be prepared for the awful, shrieking moment of truth when he realizes he is all alone on a hill ten thousand miles from home, and that he may be killed in the next second.

The young men of America, from whatever strata, are raised in a permissive society. The increasing alienation of their education from the harsher realities of life makes their reorientation, once enlisted, doubly important.

Prior to 1950 they got no reorientation. They put on the uniform, but continued to get by, doing things rather more or less. They had no time for sergeants.

As discipline deteriorated, the generals themselves were hardly affected. They still had their position, their pomp and ceremonies. Surrounded by professionals of the old school, largely field rank, they still thought their rod was iron, for, seemingly, their own orders were obeyed.

But ground battle is a series of platoon actions. No longer can a field commander stand on a hill, like Lee or Grant, and oversee his formations. Orders in combat — the orders that kill men or get them killed, are not given by generals, or even by majors. They are given by lieutenants and sergeants, and sometimes by PFC’s.

When a sergeant gives a soldier an order in battle, it must have the same weight as that of a four-star general.

Such orders cannot be given by men who are some of the boys. Men willingly take orders to die only from those they are trained to regard as superior beings.

It was not until the summer of 1950, when the legions went forth, that the generals realized what they had agreed to, and what they had wrought.

The Old Army, outcast and alien and remote from the warm bosom of society, officer and man alike, ordered into Korea, would have gone without questioning. It would have died without counting. As on Bataan, it would not have listened for the angel’s trumpet or the clarion call. It would have heard the hard sound of its own bugles, and hard-bitten, cynical, wise in bitter ways, it would have kept its eyes on its sergeants.

It would have died. It would have retreated, or surrendered, only in the last extremity. In the enemy prison camps, exhausted, sick, it would have spat upon its captors, despising them to the last.

It would have died, but it might have held.

T.R. Fehrenbach, This Kind of War: A Study in Unpreparedness, 1963.