toldinstone

Published Jan 12, 2024Chapters:

0:00 Introduction

0:34 Progress of a siege

1:55 Looting and violence

3:42 Recorded atrocities

4:45 Captives

5:27 BetterHelp

6:36 Surviving a Roman sack

7:13 Where to hide

8:27 What to do if you’re captured

9:20 Advice for women

10:09 The fate of captives

(more…)

April 18, 2024

What to do if Romans Sack your City

April 8, 2024

Beecher’s Bible: A Sharps 1853 from John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry

Forgotten Weapons

Published Jan 8, 2024On October 16, 1859 John Brown and 19 men left the Kennedy farmhouse and made their way a few miles south to the Harpers Ferry Arsenal. They planned to seize the Arsenal and use its arms — along with 200 Sharps 1853 carbines and 1,000 pikes they had previously purchased — to ignite and arm a slave revolt. Brown was a true fanatic for the abolitionist cause, perfectly willing to spill blood for a just cause. His assault on the Arsenal lasted three days, but failed to incite a rebellion. Instead of attracting local slaves to his banner, he attracted local militia and the US Marines. His force was besieged in the arsenal firehouse, and when the Marines broke through the doors they captured five surviving members of the Brown party, including Brown himself. All five were quickly tried and found guilty of murder, treason, and inciting negroes to riot. They were sentenced to death, and hanged on December 2, 1859.

Most of Brown’s 200 Sharps carbines were left in the farmhouse hideout, to be distributed when the insurrection took hold. These were found by local militia, among them the Independent Greys, and some were kept as souvenirs — including this example.

There is an intriguing historical question as to whether Brown’s raid was ultimately good for the country or not. It was extremely divisive at the time, and it can be argued that the raid was a major factor leading to Lincoln’s election and the Civil War. Could slavery have been abolished without the need for a cataclysmic war if John Brown had not fractured the Democratic Party? To what extent is killing for a cause justifiable? Do the ends always justify the means? John Brown had no doubts about his answers to these questions … but maybe he should have.

(more…)

March 19, 2024

Greek History and Civilization, Part 5 – The Greeks Fight Back

seangabb

Published Mar 17, 2024This fifth lecture in the course deals with the defeat of Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, ending with the creation of the Delian League and the varying fortunes of Xerxes and Themistocles.

(more…)

February 13, 2024

Greek History and Civilisation, Part 2 – Sparta and Athens: Contrasting Societies

seangabb

Published Feb 11, 2024This second lecture in the course contrasts Athens and Sparta, the two leading societies in Greece — one a commercial society with high levels of personal freedom and citizen participation, the other a militarised oligarchy.

[NR: Some additional information to supplement Dr. Gabb’s lecture:

– “Citizenship” in the ancient and clasical world

– Sparta had Lycurgus, while Athens had Solon … who at least actually existed

– The Constitution of Athens

– The Constitution of the Spartans

– The Myth of Spartan Equality

– Relative wealth among the Spartiates

– Sparta’s military reputation as “the best warriors in all of Greece”

– Sparta – the North Korea of the Classical era

– Spartan glossary]

(more…)

February 5, 2024

QotD: The history of slavery in America

This is therefore, in its over-reach, ideology masquerading as neutral scholarship. Take a simple claim: no aspect of our society is unaffected by the legacy of slavery. Sure. Absolutely. Of course. But, when you consider this statement a little more, you realize this is either banal or meaningless. The complexity of history in a country of such size and diversity means that everything we do now has roots in many, many things that came before us. You could say the same thing about the English common law, for example, or the use of the English language: no aspect of American life is untouched by it. You could say that about the Enlightenment. Or the climate. You could say that America’s unique existence as a frontier country bordered by lawlessness is felt even today in every mass shooting. You could cite the death of countless millions of Native Americans — by violence and disease — as something that defines all of us in America today. And in a way it does. But that would be to engage in a liberal inquiry into our past, teasing out the nuances, and the balance of various forces throughout history, weighing each against each other along with the thoughts and actions of remarkable individuals — in the manner of, say, the excellent new history of the U.S., These Truths by Jill Lepore.

But the NYT chose a neo-Marxist rather than liberal path to make a very specific claim: that slavery is not one of many things that describe America’s founding and culture, it is the definitive one. Arguing that the “true founding” was the arrival of African slaves on the continent, period, is a bitter rebuke to the actual founders and Lincoln. America is not a messy, evolving, multicultural, religiously infused, Enlightenment-based, racist, liberating, wealth-generating kaleidoscope of a society. It’s white supremacy, which started in 1619, and that’s the key to understand all of it. America’s only virtue, in this telling, belongs to those who have attempted and still attempt to end this malign manifestation of white supremacy.

I don’t believe most African-Americans believe this, outside the elites. They’re much less doctrinaire than elite white leftists on a whole range of subjects. I don’t buy it either — alongside, I suspect, most immigrants, including most immigrants of color. Who would ever want to immigrate to such a vile and oppressive place? But it is extremely telling that this is not merely aired in the paper of record (as it should be), but that it is aggressively presented as objective reality. That’s propaganda, directed, as we now know, from the very top — and now being marched through the entire educational system to achieve a specific end. To present a truth as the truth is, in fact, a deception. And it is hard to trust a paper engaged in trying to deceive its readers in order for its radical reporters and weak editors to transform the world.

Andrew Sullivan, “The New York Times Has Abandoned Liberalism for Activism”, New York, 2019-09-13.

January 19, 2024

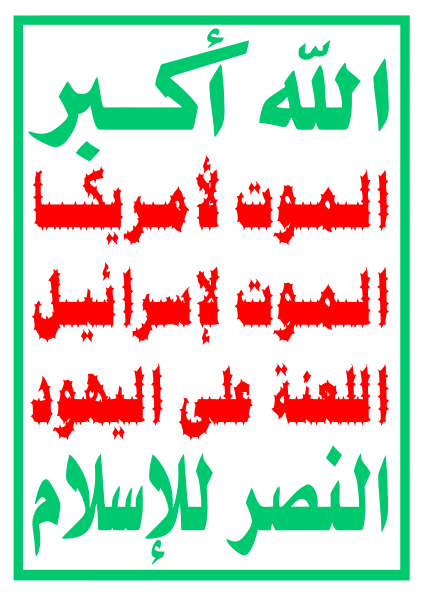

Those passionate Houthi and the Blowfish fans

Chris Selley wonders why the rest of the Canadian legacy media are being so careful to proactively curate and “contextualize” the violent and hateful message of the pro-Hamas and pro-Houthi protesters in our cities:

The Houthi Ansarullah “Al-Sarkha” banner. Arabic text:

الله أكبر (Allah is the greatest)

الموت لأمريكا (death to America)

الموت لإسرائيل (death to Israel)

اللعنة على اليهود (a curse upon the Jews)

النصر للإسلام (victory to Islam)

Image and explanatory text from Wikimedia Commons.

The record will show I had little sympathy for the Ottawa convoy crowd, especially once they had made their point and refused to go away. You can’t occupy the downtown of a G7 capital for a month. Sorry, you just can’t.

At the same time, I cringed at the media’s fevered attempts to cast the entire crowd as neo-Nazi oafs, based on what seems to have been two observed flags — one Confederate, one Nazi.

I recalled this while watching video footage of protesters in Toronto over the weekend chanting “Yemen, Yemen, make us proud! Turn another boat around!” Because the Houthis, who control Yemen’s Red Sea coast and have been waging war on commercial shipping, are about as neo-Nazi as it gets in the world nowadays.

The movement’s official slogan: “Allahu Akbar! Death to America! Death to Israel! Curse the Jews! Victory for Islam!” As if to drive home the point, there is ample video evidence of Houthi fighters chanting that slogan with their hands raised skywards in a Nazi salute.

The Houthis use child soldiers (as video evidence also makes horrifyingly plain). They are literally slavers. I have seen it suggested, by way of context, that they really don’t have that many slaves. Just a few slaves. It’s so hard to get good help.

But I haven’t seen anyone try to “contextualize” the Houthi slogan, the way Palestinian supporters will tell you “from the river to the sea” isn’t a call for Israel’s destruction and cheering for “intifada” doesn’t mean further terrorist attacks against Jews. Perhaps it’s just too big a job for even the most dedicated and creative of apologists.

Outside of the Postmedia empire, so far as I can see, not a single Canadian media outlet has seen fit to mention the chanting in Toronto streets in support of a rabidly antisemitic death cult. You can read several articles, however, about how Canadian media are terribly biased against the Palestinian cause. It’s ludicrous.

A nice little illustration, as the National Post‘s Tristin Hopper noted in November: When the convoy crowd appropriated Terry Fox’s statue, just opposite Parliament Hill, for their “mandate freedom” message, the Laurentian bubble nearly burst with righteous fury. When pro-Palestinian protesters draped a keffiyeh over Fox’s shoulders and had their kids pose with him, there was all but total silence.

Of course, flamboyant media double-standards aren’t the worst of our problems.

January 16, 2024

Mark Twain’s Huck Finn

In Quillette, Tim DeRoche re-reads Huck Finn after finally engaging with Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and finds the two books are not in opposition but should be read as complementing each other:

Twain scholar Laura Trombley (now the President of Southwestern University in Texas) once told me that Huck Finn isn’t about slavery. “It’s about an abused boy looking for a safe haven,” she said. It was daring for Twain to give a voice to the untutored, unwashed son of the town drunk.

You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer”; but that ain’t no matter. That book was made by Mr. Mark Twain, and he told the truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth. That is nothing. I never seen anybody but lied one time or another …

Huck’s voice, often described as “realistic”, is actually a highly stylized literary device and a brilliant riff on how real boys talk. In these first few sentences, Twain inserts himself into the story and sets his protagonist up to be an unreliable narrator, as Huck admits that there will be “stretchers” of his own along the way.

Huck Finn is our national epic, much like The Odyssey is for Greece or the Nibelungenlied is for Germany. Like those older epics, Huck Finn can be read as version of a Jungian myth, in which the hero descends into the Underworld, undergoes trials and tribulations, and returns to us reborn. This story of two travelers on an epic journey is an archetype of our culture, which is why it is retold with such frequency. It’s possible to read every American road novel or movie as a reworking of Huck Finn.

Twain may not have written in verse, but Huck’s narration is beautiful and lyrical and so distinctively American that it has influenced generations of American writers, both popular and literary. That indelible voice, at once innocent and highly perceptive, is the fixed moral point from which Twain can then satirize so many different segments of his beloved country — preachers, con men, politicians, actors, and ordinary gullible Americans.

The book has been criticized as one of the first “white savior” narratives, but this gets it exactly backwards. Huck doesn’t save anyone in the novel. (One of Jane Smiley’s criticisms, in fact, is that Huck doesn’t “act” to save his friend.) It is actually Jim, the slave, who saves Huck — both literally and figuratively. It is Jim who provides Huck with a safe haven, and it is Jim who calls Huck to account when Huck treats him as less than human: “En all you wuz thinkin ’bout wuz how you could make a fool uv ole Jim wid a lie. Dat truck dah is trash, en trash is what people is dat puts dirt on de head er de fren’s en makes ’em ashamed.”

Huck eventually humbles himself before Jim and tells us, “I didn’t do him no more mean tricks, and I wouldn’t done that one if I’d a knowed it would make him feel that way.” Huck may be the protagonist of this story, but the slave Jim is its moral hero. It is Jim who reveals himself to be a fugitive slave so that Tom Sawyer can get medical attention for his gunshot wound. And after he is freed from slavery, Jim heads home to assume his responsibilities as a husband and father.

In contrast to Jim, Huck yearns for adventure and escape. Forced to live with the Widow Douglas and Miss Watson at the start of the book, he resents their attempts to “sivilize” him. He feels “all cramped up” by the clothes they make him wear, and he dismisses their Biblical teaching because he “don’t take no stock in dead people”. Instead of returning home with Jim, Huck tells us that he intends to “light out for the territory”. He represents one aspect of the American spirit — ironic, secular, individualistic.

January 12, 2024

Slavery in the Roman World: A Lecture Given in September 2023

seangabb

Published 24 Sept 2023A lecture given in absentia to the 2023 meeting of the Property and Freedom Society in Bodrum. The subject is Slavery in the Roman World. It covers these issues:

Introduction: Sean Gabb, face to camera – 00:00:00

Classical Liberalism, the Natural Law and Slavery – 00:06:38

The Growth of Roman Slavery – 00:16:27

Slave Markets – 00:21:20

The Valuation of Slaves – 00:24:07

Slave Occupations – 00:29:41

The Treatment of Slaves: Galen and the Broken Cup – 00:33:04

Sex and Slavery – 00:38:32

Other Mistreatment of Slaves – 00:00:00

Escape and Punishment – 00:45:49

Slaves and the Arena – 00:48:10

The Moral Effects of Slavery – 00:49:18

The Slave Revolts – 00:58:20

Manumission – 01:03:14

Conclusion and Bibliography – 01:10:20

(more…)

January 11, 2024

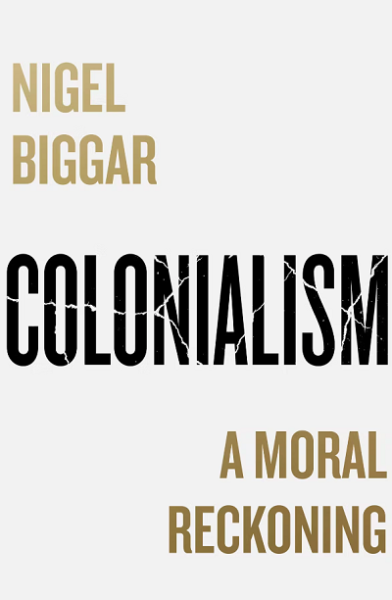

Pushing back against the Colonialism Narrative

At Samizdata, Brendan Westbridge praises Nigel Biggar’s 2023 book Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning:

He examines the various claims that the “de-colonisers” make: Amritsar, slavery, Benin, Boer War, Irish famine. In all cases he finds that their claims are either entirely ungrounded or lack vital information that would cast events in a very different light. Amritsar? Dyer was dealing with political violence that had led to murder. Some victims had been set alight. Anyway, he was condemned for his actions by the British authorities and, indeed, his own standing orders. Slavery? Everyone had it and Britain was the first to get rid of it. Benin? They had killed unarmed ambassadors. Irish famine? They tried to relieve it but they were quite unequal to the size of the task. In the case of Benin he comes very close to accusing the leading de-coloniser of knowingly lying. The only one of these where I don’t think he is so convincing is the Boer War. He claims that Britain was concerned about the future of the Cape and especially the Simonstown naval base and also black rights. I think it was the pursuit of gold even if it does mean agreeing with the communist Eric Hobsbawm.

He is far too polite about the “de-colonisers”. They are desperate to hammer the square peg of reality into their round-hole of a theory. To this end they claim knowledge they don’t have, gloss over inconvenient facts, erect theories that don’t bear scrutiny and when all else fails: lie. Biggar tackles all of these offences against objectivity with a calmness and a politeness that you can bet his detractors would never return.

The communists – because they are obsessed with such things and are past masters at projection – like to claim that there was an “ideology” of Empire. Biggar thinks this is nonsense. As he says:

There was no essential motive or set of motives that drove the British Empire. The reasons why the British built an empire were many and various. They differed between trader, migrant, soldier, missionary, entrepreneur, financier, government official and statesman. They sometimes differed between London, Cairo, Cape Town and Calcutta. And all of the motives I have unearthed in this chapter were, in themselves, innocent: the aversion to poverty and persecution, the yearning for a better life, the desire to make one’s way in the world, the duty to satisfy shareholders, the lure of adventure, cultural curiosity, the need to make peace and keep it, the concomitant need to maintain martial prestige, the imperative of gaining military or political advantage over enemies and rivals, and the vocation to lift oppression and establish stable self-government. There is nothing morally wrong with any of these. Indeed, the last one is morally admirable.

One of the benefits of the British Empire is that it tended to put a stop to local wars. How many people lived because of that? But that leads us on to another aspect. Almost no one ever considers what went on before the Empire arrived. Was it better or worse than went before it? Given that places like Benin indulged in human sacrifice, I would say that in many cases the British Empire was an improvement. And if we are going to talk about what went before what about afterwards? He has little to say about what newly-independent countries have done with their independence. The United States, the “white” (for want of a better term) Commonwealth and Singapore have done reasonably well. Ireland is sub-par but OK. Africa, the Caribbean and the Indian sub-continent have very little to show for themselves. This may explain why Britain needed very few people to maintain the Empire. At one point he points out that at the height of the Raj the ratio of Briton to native was 1 to 1000. That implies a lot of consent. Tyrannies need a lot more people.

The truth of the matter is that talk of reparations is rooted in the failure of de-colonisation. If Jamaica were a nicer place to live than the UK, if Jamaica had a small boats crisis rather than the UK then no one would be breathing a word about reparations or colonial guilt. All this talk is pure deflection from the failure of local despots to make the lives of their subjects better.

Biggar has nothing to say about what came after the empire and he also has little to say about how it came about in the first place – so I’ll fill in that gap. Britain acquired an empire because it could. Britain was able to acquire an Empire because it mastered the technologies needed to do it to a higher level and on a greater scale than anyone else. Britain mastered technology because it made it possible to prosper by creating wealth. That in itself was a moral achievement.

QotD: Slavery in the United States

Of all the tragic facts about the history of slavery, the most astonishing to an American today is that, although slavery was a worldwide institution for thousands of years, nowhere in the world was slavery a controversial issue prior to the 18th century. People of every race and color were enslaved – and enslaved others. White people were still being bought and sold as slaves in the Ottoman Empire, decades after American blacks were freed.

Everyone hated the idea of being a slave but few had any qualms about enslaving others. Slavery was just not an issue, not even among intellectuals, much less among political leaders, until the 18th century – and then it was an issue only in Western civilization. Among those who turned against slavery in the 18th century were George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry and other American leaders. You could research all of the 18th century Africa or Asia or the Middle East without finding any comparable rejection of slavery there. But who is singled out for scathing criticism today? American leaders of the 18th century.

Deciding that slavery was wrong was much easier than deciding what to do with millions of people from another continent, of another race, and without any historical preparation for living as free citizens in a society like that of the United States, where they were 20 percent of the population.

It is clear from the private correspondence of Washington, Jefferson, and many others that their moral rejection of slavery was unambiguous, but the practical question of what to do now had them baffled. That would remain so for more than half a century.

In 1862, a ship carrying slaves from Africa to Cuba, in violation of a ban on the international slave trade, was captured on the high seas by the U.S. Navy. The crew were imprisoned and the captain was hanged in the United States – despite the fact that slavery itself was still legal at the time in Africa, Cuba, and in the United States. What does this tell us? That enslaving people was considered an abomination. But what to do with millions of people who were already enslaved was not equally clear.

That question was finally answered by a war in which one life was lost [620,000 Civil War casualties] for every six people freed [3.9 million]. Maybe that was the only answer. But don’t pretend today that it was an easy answer – or that those who grappled with the dilemma in the 18th century were some special villains when most leaders and most people around the world saw nothing wrong with slavery.

Incidentally, the September 2003 issue of National Geographic had an article about the millions of people still enslaved around the world right now. But where is the moral indignation about that?

Thomas Sowell, The Thomas Sowell Reader, 2011.

December 29, 2023

The Christianization of England

Ed West‘s Christmas Day post recounted the beginnings of organized Christianity in England, thanks to the efforts of Roman missionaries sent by Pope Gregory I:

“Saint Augustine and the Saxons”

Illustration by Joseph Martin Kronheim from Pictures of English History, 1868 via Wikimedia Commons.

The story begins in sixth century Rome, once a city of a million people but now shrunk to a desolate town of a few thousand, no longer the capital of a great empire of even enjoying basic plumbing — a few decades earlier its aqueducts had been destroyed in the recent wars between the Goths and Byzantines, a final blow to the great city of antiquity. Under Pope Gregory I, the Church had effectively taken over what was left of the town, establishing it as the western headquarters of Christianity.

Rome was just one of five major Christian centres. Constantinople, the capital of the surviving eastern Roman Empire, was by this point far larger, and also claimed leadership of the Christian world — eventually the two would split in the Great Schism, but this was many centuries away. The other three great Christian centres — Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch — would soon fall to Islam, a turn of events that would strengthen Rome’s spiritual position. And it was this Roman version of Christianity which came to shape the Anglo-Saxon world.

Gregory was a great reformer who is viewed by some historians as a sort of bridge between Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the founder of a new and reborn Rome, now a spiritual rather than a military empire. He is also the subject of the one great stories of early English history.

One day during the 570s, several years before he became pontiff, Gregory was walking around the marketplace when he spotted a pair of blond-haired pagan slave boys for sale. Thinking it tragic that such innocent-looking children should be ignorant of the Lord, he asked a trader where they came from, and was told they were “Anglii”, Angles. Gregory, who was fond of a pun, replied “Non Angli, sed Angeli” (not Angles, but angels), a bit of wordplay that still works fourteen centuries later. Not content with this, he asked what region they came from and was told “Deira” (today’s Yorkshire). “No,” he said, warming to the theme and presumably laughing to himself, “de ira” — they are blessed.

Impressed with his own punning, Gregory decided that the Angles and Saxons should be shown the true way. A further embellishment has the Pope punning on the name of the king of Deira, Elle, by saying he’d sing “hallelujah” if they were converted, but it seems dubious; in fact, the Anglo-Saxons were very fond of wordplay, which features a great deal in their surviving literature and without spoiling the story, we probably need to be slightly sceptical about whether Gregory actually said any of this.

The Pope ordered an abbot called Augustine to go to Kent to convert the heathens. We can only imagine how Augustine, having enjoyed a relatively nice life at a Benedictine monastery in Rome, must have felt about his new posting to some cold, faraway island, and he initially gave up halfway through his trip, leaving his entourage in southern Gaul while he went back to Rome to beg Gregory to call the thing off.

Yet he continued, and the island must have seemed like an unimaginably grim posting for the priest. Still, in the misery-ridden squalor that was sixth-century Britain, Kent was perhaps as good as it gets, in large part due to its links to the continent.

Gaul had been overrun by the Franks in the fifth century, but had essentially maintained Roman institutions and culture; the Frankish king Clovis had converted to Catholicism a century before, following relentless pressure from his wife, and then as now people in Britain tended to ape the fashions of those across the water.

The barbarians of Britain were grouped into tribes led by chieftains, the word for their warlords, cyning, eventually evolving into its modern usage of “king”. There were initially at least twelve small kingdoms, and various smaller tribal groupings, although by Augustine’s time a series of hostile takeovers had reduced this to eight — Kent, Sussex, Essex, and Wessex (the West Country and Thames Valley), East Anglia, Mercia (the Midlands), Bernicia (the far North), and Deira (Yorkshire).

In 597, when the Italian delegation finally finished their long trip, Kent was ruled by King Ethelbert, supposedly a great-grandson of the semi-mythical Hengest. The king of Kent was married to a strong-willed Frankish princess called Bertha, and luckily for Augustine, Bertha was a Christian. She had only agreed to marry Ethelbert on condition that she was allowed to practise her religion, and to keep her own personal bishop.

Bertha persuaded her husband to talk to the missionary, but the king was perhaps paranoid that the Italian would try to bamboozle him with witchcraft, only agreeing to meet him under an oak tree, which to the early English had magical properties that could overpower the foreigner’s sorcery. (Oak trees had a strong association with religion and mysticism throughout Europe, being seen as the king of the trees and associated with Woden, Zeus, Jupiter, and all the other alpha male gods.)

Eventually, and persuaded by his wife, Ethelbert allowed Augustine to baptise 10,000 Kentish men on Christmas Day, 597, according to the chronicles. This is probably a wild exaggeration; 10,000 is often used as a figure in medieval history, and usually just means “quite a lot of people”.

December 19, 2023

Henry Dundas, cancelled because he didn’t do even more, sooner to abolish slavery in the British Empire

Toronto’s usual progressive suspects are still eager to rename Dundas Street because (they claim) Henry Dundas was involved in the slave trade. Which is true, if you torture the words enough. His involvement was to ensure the passage of the first successful abolitionist motion through Parliament by working out a compromise between the hard abolitionists (who wanted slavery ended immediately) and the anti-abolitionists. This is enough, in the views of the very, very progressive activists of today to merit our modern version of damnatio memoriae:

Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville.

Portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence. National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.

Henry Dundas never travelled to British North America and likely spent very little of his 69 years ever thinking about it. He was an influential Scottish career politician whose name adorns the street purely because he happened to be British Home Secretary when it was surveyed in 1793.

But after 230 years, activists led an ultimately successful a push for the Dundas name to be excised from the 23-kilometre street. As Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow said in deliberations over the name change, Dundas’s actions in relation to the Atlantic slave trade were “horrific“.

Was Dundas a slaveholder? Did he profit from the slave trade? Did he use his influence to advance or exacerbate the business of slavery?

No; Dundas was a key figure in the push to abolish slavery across the British Empire. The reason activists want his name stripped from Dundas Street is because he didn’t do it fast enough.

[…]

The petition was piggybacking off a similar anti-Dundas movement in the U.K. – which itself seems to have been inspired by Dundas’s portrayal as a villain in the 2006 film Amazing Grace, a fictionalized portrayal of the British anti-slavery movement.

Dundas was responsible for inserting the word “gradually” into an iconic 1792 Parliamentary motion calling for the end of the Atlantic slave trade. A legislated end to the trade wouldn’t come until 1807, followed by an 1833 bill mandating the total abolition of slavery across the British Empire.

The accusation is that – if not for Dundas – the unamended motion would have passed and the British slave trade would have ended 15 years earlier.

But according to the 18th century historians who have been brought out of the woodwork by the Cancel Dundas movement, Henry Dundas was a man working within the political realities of a Britain that wasn’t yet altogether convinced that slavery was a bad thing.

The year before Dundas’ “gradual” amendment secured passage for the motion, the House of Commons had rejected a similar motion for immediate abolition.

“Dundas’s amendment at least got an anti-slavery statement adopted — the first,” wrote Lynn McDonald, a fellow of the Royal Historical Society, in August. McDonald added that, in any case, it was just a non-binding motion; any actual law wouldn’t have gotten past the House of Lords.

The parliamentary record from this time survives, and Dundas was open about the fact that he “entertained the same opinion” on slavery as the famed abolitionist William Wilberforce, but favoured a more practical means of stamping it out.

“Allegations … that abolition would have been achieved sooner than 1807 without his opposition, are fundamentally mistaken,” reads one lengthy Dundas defence in the journal Scottish Affairs.

“Historical realities were much more nuanced and complex in the slave trade abolition debates of the 1790s and early 1800s than a focus on the role and significance of one politician suggests,” wrote the paper, adding that although Wilberforce opposed Dundas’ insertion of the word “gradually,” the iconic anti-slavery figure “later admitted that abolition had no chance of gaining approval in the House of Lords and that Dundas’s gradual insertion had no effect on the voting outcome.”

Meanwhile, the British abolition of slavery actually has some indirect ties to the road that bears Dundas’s name.

The road’s construction was overseen by John Graves Simcoe, the British Army general that Dundas had picked to be Lieutenant Governor of the colony of Upper Canada.

The same year he started building Dundas Street, Simcoe signed into law an act banning the importation of slaves to Upper Canada – and setting out a timeline for the emancipation of the colony’s existing slaves. It was the first anti-slavery legislation in the British Empire, and it was partially intended as a middle finger to the Americans’ first Fugitive Slave Act, passed that same year.

December 10, 2023

QotD: Roman citizenship

As with other ancient self-governing citizen bodies, the populus Romanus (the Roman people – an idea that was defined by citizenship) restricted political participation to adult citizen males (actual office holding was further restricted to adult citizen males with military experience, Plb. 6.19.1-3). And we should note at the outset that citizenship was stratified both by legal status and also by wealth; the Roman Republic openly and actively counted the votes of the wealthy more heavily than those of the poor, for instance. So let us avoid the misimpression that Rome was an egalitarian society; it was not.

The most common way to become a Roman citizen was by birth, though the Roman law on this question is more complex and centers on the Roman legal concept of conubium – the right to marry and produce legally recognized heirs under Roman law. Conubium wasn’t a right held by an individual, but a status between two individuals (though Roman citizens could always marry other Roman citizens). In the event that a marriage was lawfully contracted, the children followed the legal status of their father; if no lawfully contracted marriage existed, the child followed the status of their mother (with some quirks; Ulpian, Reg. 5.2; Gaius, Inst. 1.56-7 – on the quirks and applicability in the Republic and conubium in general, see S.T. Roselaar, “The Concept of Conubium in the Roman Republic” in New Frontiers: Law and Society in the Roman World, ed. P.J. du Plessis (2013)).

Consequently the children of a Roman citizen male in a legal marriage would be Roman citizens and the children of a Roman citizen female out of wedlock would (in most cases; again, there are some quirks) be Roman citizens. Since the most common way for the parentage of a child to be certain is for the child to be born in a legal marriage and the vast majority of legal marriages are going to involve a citizen male husband, the practical result of that system is something very close to, but not quite exactly the same as, a “one parent” rule (in contrast to Athens’ two-parent rule). Notably, the bastard children of Roman women inherited their mother’s citizenship (though in some cases, it would be necessarily, legally, to conceal the status of the father for this to happen, see Roselaar, op. cit., and also B. Rawson, “Spruii and the Roman View of Illegitimacy” in Antichthon 23 (1989)), where in Athens, such a child would have been born a nothos and thus a metic – resident non-citizen foreigner.

The Romans might extend the right of conubium with Roman citizens to friendly non-citizen populations; Roselaar (op. cit.) argues this wasn’t a blanket right, but rather made on a community-by-community basis, but on a fairly large scale – e.g. extended to all of the Campanians in 188 B.C. Importantly, Roman colonial settlements in Italy seem to pretty much have always had this right, making it possible for those families to marry back into the citizen body, even in cases where setting up their own community had caused them to lose all or part of their Roman citizenship (in exchange for citizenship in the new community).

The other long-standing way to become a Roman citizen was to be enslaved by one and then freed. An enslaved person held by a Roman citizen who was then freed (or manumitted) became a libertus (or liberta), by custom immediately the client of their former owner (this would be made into law during the empire) and by law a Roman citizen, although their status as a freed person barred them from public office. Since they were Roman citizens (albeit with some legal disability), their children – assuming a validly contracted marriage – would be full free-born Roman citizens, with no legal disability. And, since freedmen and freedwomen were citizens, they also could contract valid marriages with other Roman citizens, including freeborn ones […]. While most enslaved people in the Roman world had little to no hope of ever being manumitted (enslaved workers, for instance, on large estates far from their owners), Roman economic and social customs functionally required a significant number of freed persons and so a meaningful number of new Roman citizens were always being minted in the background this way. Rome’s apparent liberality with admission into citizenship seems to have been a real curiosity to the Greek world.

These processes thus churned in the background, minting new Romans on the edges of the populus Romanus who subsequently became full members of the Roman community and thus shared fully in the Roman legal identity.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-25.

November 10, 2023

QotD: Economic distortions of slavery in the Antebellum South

This notion that slavery somehow benefited the entire economy is a surprisingly common one and I want to briefly refute it. This is related to the ridiculously bad academic study (discussed here) that slave-harvested cotton accounted for nearly half of the US’s economic activity, when in fact the number was well under 10%. I assume that activists in support of reparations are using this argument to make the case that all Americans, not just slaveholders, benefited from slavery. But this simply is not the case.

At the end of the day, economies grow and become wealthier as labor and capital are employed more productively. Slavery does exactly the opposite.

Slaves are far less productive than free laborers. They have no incentive to do any more work than the absolute minimum to avoid punishment, and have zero incentive (and a number of disincentives) to use their brain to perform tasks more intelligently. So every slave is a potentially productive worker converted into an unproductive one. Thus, every dollar of capital invested in a slave was a dollar invested in reducing worker productivity.

As a bit of background, the US in the early 19th century had a resource profile opposite from the old country. In Europe, labor was over-abundant and land and resources like timber were scarce. In the US, land and resources were plentiful but labor was scarce. For landowners, it was really hard to get farm labor because everyone who came over here would quickly quit their job and headed out to the edge of settlement and grabbed some land to cultivate for themselves.

In this environment the market was sending pretty clear pricing signals — that it was simply not a good use of scarce labor resources to grow low margin crops on huge plantations requiring scores or hundreds of laborers. Slave-owners circumvented this pricing signal by finding workers they could force to work for free. Force was used to apply high-value labor to lower-value tasks. This does not create prosperity, it destroys it.

As a result, whereas $1000 invested in the North likely improved worker productivity, $1000 invested in the South destroyed it. The North poured capital into future prosperity. The South poured it into supporting a dead-end feudal plantation economy. As a result the south was impoverished for a century, really until northern companies began investing in the South after WWII. If slavery really made for so much of an abundance of opportunities, then why did very few immigrants in the 19th century go to the South? They went to the industrial northeast or (as did my grandparents) to the midwest. The US in the 19th century was prosperous despite slavery in the south, not because of it.

Warren Meyer, “Slavery Made the US Less Prosperous, Not More So”, Coyote Blog, 2019-07-12.

October 9, 2023

QotD: Roman views of sexual roles

There is always a temptation to emphasise the way in which the Romans are like us, a mirror held up to our own civilisation. But what is far more interesting is the way in which they are nothing like us, because it gives you a sense of how various human cultures can be. You assume that ideas of sex and gender are pretty stable, and yet the Roman understanding of these concepts was very, very different to ours. For us, I think, it does revolve around gender — the idea that there are men and there are women — and, obviously, that can be contested, as is happening at the moment. But the fundamental idea is that you are defined by your gender. Are you heterosexual or homosexual? That’s probably the great binary today.

For the Romans, this is not a binary. There’s a description in Suetonius’s imperial biography of Claudius: “He only ever slept with women.” And this is seen as an interesting foible in the way that you might say of someone, he only ever slept with blondes. I mean, it’s kind of interesting, but it doesn’t define him sexually. Similarly, he says of Galba, an upright embodiment of ancient republican values: “He only ever slept with males.” And again, this is seen as an eccentricity, but it doesn’t absolutely define him. What does define a Roman in the opinion of Roman moralists is basically whether you are — and I apologise for the language I’m now going to use — using your penis as a kind of sword, to dominate, penetrate and subdue. And the people who were there to receive your terrifying, thrusting, Roman penis were, of course, women and slaves: anyone who is not a citizen, essentially. So the binary is between Roman citizens, who are all by definition men, and everybody else.

A Roman woman, if she’s of citizen status, can’t be used willy-nilly — but pretty much anyone else can. That means that if you’re a Roman householder, your family is not just your blood relatives: it’s everybody in your household. It’s your dependents; your slaves. You can use your slaves any way you want. And if you’re not doing it, then there’s something wrong with you. The Romans had the same word for “urinate” and “ejaculate”, so the orifices of slaves — and they could be men, women, boys or girls — were seen as the equivalent of urinals for Roman men. Of course, this is very hard for us to get our heads around today.

The most humiliating thing that could happen to a Roman male citizen was to be treated like a woman — even if it was involuntary. For them, the idea that being trans is something to be celebrated would seem the most depraved, lunatic thing that you could possibly argue. Vitellius, who ended up an emperor, was known his whole life as “sphincter”, because it was said that as a young man he had been used like a girl by Tiberius on Capri. It was a mark of shame that he could never get rid of. There was an assumption that the mere rumour of being treated in this way would stain you for life; and if you enjoy it, then you are absolutely the lowest of the low.

Tom Holland, “The depravity of the Roman Peace”, UnHerd, 2023-07-07.