Real Time History

Published Dec 1, 2023December 7, 1941: The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor shocked the world and brought the US into the Second World War. But why did the Japanese resort to such an attack against a powerful rival and what did it have to do with the Japanese war in China?

(more…)

April 22, 2024

Did Japan Attack Pearl Harbor Because Of China?

March 31, 2024

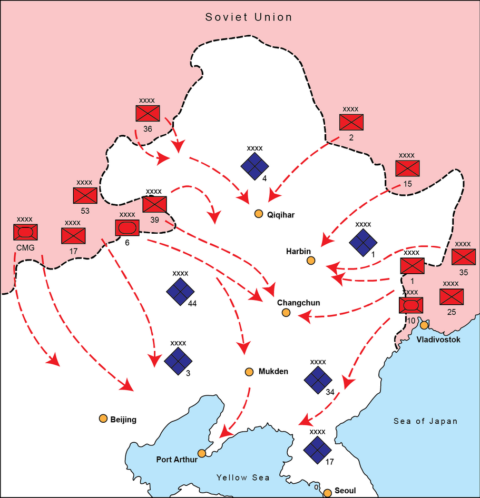

August, 1945 – The Soviets enter the war in China

Big Serge outlines the Soviet invasion of Manchuria in August 1945 and its devastating impact on the Japanese Kwantung Army, finally shattering any remaining illusions that the Soviets would broker a peace between Japan and the western allies:

The Second World War had a strange sort of symmetry to it, in that it ended much the way it began: namely, with a well-drilled, technically advanced and operationally ambitious army slicing apart an overmatched foe. The beginning of the war, of course, was Germany’s rapid annihilation of Poland, which rewrote the book on mechanized operations. The end of the war — or at least, the last major land campaign of the war — was the Soviet Union’s equally totalizing and rapid conquest of Manchuria in August 1945.

Manchuria was one of the many forgotten fronts of the war, despite being among the oldest. The Japanese had been kicking around in Manchuria since 1931, consolidating a pseudo-colony and puppet state ostensibly called Manchukuo, which served as a launching pad for more than a decade of Japanese incursions and operations in China. For a brief period, the Asian land front had been a major pivot of world affairs, with the Japanese and the Red Army fighting a series of skirmishes along the Siberian-Manchurian border, and Japan’s enormously violent 1937 invasion of China serving as the harbinger of global war. But events had pulled attention and resources in other directions, and in particular the events of 1941, with the outbreak of the cataclysmic Nazi-Soviet War and the Great Pacific War. After a few years as a major geopolitical pivot, Manchuria was relegated to the background and became a lonely, forgotten front of the Japanese Empire.

Until 1945, that is. Among the many topics discussed at the Yalta Conference in the February of that year was the Soviet Union’s long-delayed entry into the war against Japan, opening an overland front against Japan’s mainland colonies. Although it seems relatively obvious that Japanese defeat was inevitable, given the relentless American advance through the Pacific and the onset of regular strategic bombing of the Japanese home islands, there were concrete reasons why Soviet entry into the war was necessary to hasten Japanese surrender.

More specifically, the Japanese continued to harbor hopes late into the war that the Soviet Union would choose to act as a mediator between Japan and the United States, negotiating a conditional end to war that fell short of total Japanese surrender. Soviet entry into the war against Japan would dash these hopes, and overrunning Japanese colonies in Asia would emphasize to Tokyo that they had nothing left to fight for. Against this backdrop, the Soviet Union spent the summer of 1945 preparing for one final operation, to smash the Japanese in Manchuria.

The Soviet maneuver scheme was tightly choreographed and well conceived — representing in many ways a sort of encore, perfected demonstration of the operational art that had been developed and practiced at such a high cost in Europe. Taking advantage of the fact that Manchuria already represented a sort of salient — bulging as it did into the Soviet Union’s borders — the plan of attack called for a series of rapid, motorized thrusts towards a series of rail and transportation hubs in the Japanese rear (from north to south, these were Qiqihar, Harbin, Changchun, and Mukden).

By rapidly bypassing the main Japanese field armies and converging on transit hubs in the rear, the Red Army would effectively isolate all the Japanese armies both from each other and from their lines of communication to the rear, effectively slicing Manchuria into a host of separated pockets.

There were, of course, a host of reasons why the Japanese had no hope of resisting this onslaught. In material terms, the overmatch was laughable. The Soviet force was lavishly equipped and bursting with manpower and equipment — three fronts totaling more than 1.5 million men, 5,000 armored vehicles, and tens of thousands of artillery pieces and rocket launchers.

The Japanese (including Manchurian proxy forces) had a paper strength of perhaps 900,000 men, but the vast majority of this force was unfit for combat. Virtually all of the Japanese army’s veteran units and equipment had been steadily transferred to the Pacific in a cannibalizing trickle — a vain attempt to slow the American onslaught. Accordingly, by 1945 the Japanese Kwantung Army had been reduced to a lightly armed and poorly trained conscript force that was suitable only for police actions and counterinsurgency against Chinese partisans.

Really, there was nothing for the Japanese to do. The Kwantung Army had far less of a fighting chance in 1945 than the Wehrmacht had in the spring of that year, and everyone knows how that turned out. Unsurprisingly, then, the Soviets broke through everywhere at will when they began the assault on August 9. Soviet armored forces found it trivially easy to overrun Japanese positions (armed primarily with archaic, low caliber antitank weaponry that could not penetrate Soviet armor even at point blank range), and by the end of the first day the Soviet pincers were driving far into the rear.

It is easy, in hindsight, to write off the Manchuria campaign as something of a farce: a highly experienced, richly equipped Red Army overrunning and abusing an overmatched and threadbare Japanese force. In many ways, this is an accurate assessment. However, what the offensive demonstrated was the Red Army’s extreme proficiency at organizing enormous operations and moving at high speeds. By August 20 (after only 11 days), the Red Army had reached the Korean border and captured all their objectives in the Japanese rear, in effect completely overrunning a theater that was even larger than France. Many of the Soviet spearheads had driven more than three hundred miles in a little over a week.

To be sure, the combat aspects of the operation were farcical, given the totalizing level of Soviet overmatch. Red Army losses were something like 10,000 men — a trivial number for an operation of this scale. What was genuinely impressive — and terrifying to alert observers — was the Red Army’s clear demonstration of its capacity to organize operations that were colossal in scale, both in the size of the forces and the distances covered.

More to the point, the Japanese had no prospect of stopping this colossal steel tidal wave, but who did? All the great armies of the world had been bankrupted and shattered by the great filter of the World Wars — the French, the Germans, the British, the Japanese, all gone, all dying. Only the US Army had any prospect of resisting this great red tidal wave, and that force was on the verge of a rapid demobilization following the surrender of Japan. The enormous scale and operational proclivities of the Red Army thus presented the world with an entirely new sort of geostrategic threat.

February 10, 2024

QotD: When Manchuria became Manchukuo

Back around the turn of the 20th century, the Russians decided to build a railroad across Siberia, the better to (among other things) supply their spiffy new naval base at Port Arthur, on the strategic Liaodong Peninsula (linking up with their Chinese Eastern Railway). This pissed off the Japanese, who claimed the Peninsula by right of conquest in the First Sino-Japanese War. Unpleasantness ensued.

Further unpleasantness ensued in the wake of World War I, when both Imperial Russia and Republican China collapsed. The Japanese had a big railroad project of their own going in the Kwantung Leased Territory, which was threatened by the chaos. Moreover, the big Japanese railroad project had grown — as Japanese industrial concerns tend to do — into a ginormous, all-encompassing combine known as Mantetsu.

So far, so recondite, I suppose, but stop me if this part sounds familiar: Mantetsu was so big, and so shady, that it was all but impossible to tell where “the guys running Mantetsu” ended and “the Japanese government” began. And it gets better: Thanks to the Japanese Empire’s distinctive (to put it mildly, and kindly) administrative structure, it was equally hard to tell where “the Japanese government” ended and “the Japanese military” began. Even better — by which I mean much, much worse, but again feel free to stop me when this sounds familiar — “the Japanese military” was itself composed of several wildly different, mutually hostile chains of command, all competing with each other for political power, economic access, and glory. Best of all — by which, again, I mean worst — since Mantetsu was so big, and so wired-in to every level of the Japanese government, it basically got its own army, which was effectively separate even from the Army High Command back in Tokyo.

Here again, the granular details are insanely complex, and I’m not qualified to walk you through them, but the upshot is: Thanks to all of the above, plus the active enmity of the rapidly-rearming Soviet Union and the rapidly-accelerating chaos of the Warlord Period in China, Japan’s foreign policy ended up being dictated by the Kwantung Army, with almost no reference to even the High Command, let alone the civilian politicians, back in Tokyo. A particular warlord giving the Mantetsu Board of Directors — or, you know, whoever — grief? No problem — boom! Oh, that didn’t solve the problem, and now the politicians are dragging their feet? Might as well blow up a different part of your own railway, seize a whole bunch of territory on that flimsy pretext, and set up a puppet government to give you cover …

I don’t expect y’all to follow all the links right away, so trust me on this: Nobody involved in any of that stuff ranked higher than colonel. Indeed, the guy most “responsible” — if that’s really the word — for all of this stuff was a staff pogue, also a colonel, named Kanji Ishiwara. He and another staff pogue, Seishiro Itagaki, who was head of the Kwantung Army’s intelligence section, orchestrated the Japanese invasion of China, and while it’s oversimplifying things a bit too much to say those two clowns started World War II in the Pacific, I’m not stopping you from saying it.

From there, events took on a logic of their own. The rest of the Army was soon committed to the war in North China, which rapidly became the war in all the rest of China. The Navy, not wanting to let the Army hog all the glory, had gotten in on the war a few years prior to the Marco Polo Bridge, and soon enough they were causing all kinds of international grief on their own account. Put simply, but not unfairly, you had the Navy chasing the Army, and the Army chasing itself, all across China, with the civilian politicians lagging way behind in the rear, desperately trying to catch up, or even just figure out what the hell was going on …

Severian, “Lessons from Manchuria”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-04-21.

March 11, 2023

Why Japan Surrendered in WW2: Stalin or the Bomb?

Real Time History

Published 10 Mar 2023

It’s common wisdom that the nuclear bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki caused the Japanese surrender at the end of the 2nd World War. However, there has been a fierce historical debate if this narrative omits the role of the Soviet invasion of Manchuria in August 1945 — or if this invasion was actually the main cause for the surrender.

(more…)

December 3, 2022

QotD: Mantetsu and the Kwantung Army

When the Japanese decided to become a modern power, they consciously chose to emulate American business practices. But these were the business practices of the Gilded Age, so Japanese businesses ran in a way that would have the most hardened Robber Baron drooling — horizontal integration, vertical integration, trusts, combines, mergers, the works.

Thus the South Manchuria Railway Corporation, originally contracted to develop a defunct line in a disputed territory, soon developed into a full-spectrum enterprise. Pretty much all heavy industry in the Japanese areas of Manchuria were divisions of Mantetsu. But since all the heavy industry depended on mines, and transportation, and food and housing for workers, and banks, and schools for the workers’ children, etc., pretty soon Mantetsu ran all of that, too. By the late 1920s, you could argue that Mantetsu was almost its own country.

It even had its own army, and that’s where things get really interesting.

The Kwantung Army was the security force assigned to the South Manchuria Railway Zone. The Japanese weren’t stupid; they knew the perils of independent commands far from home, and they rotated units through with some regularity. Nonetheless, the command staff remained fairly stable over the years … and so did Mantetsu’s.

The Japanese weren’t stupid, but they were people, and people being people, soon enough the lines between the Kwantung Army and Mantetsu began to blur. And since the lines between Mantetsu, the Imperial Army, and the government were already pretty blurry, pretty soon the concerns of one became the concern of all. (Nor was the Navy left out, though I’m not discussing them in order to keep it simple. They were up to their eyeballs in Mantetsu, too, because warships need lots of steel and steel comes from Manchuria).

A small but highly committed and totally ideologized faction developed inside the Kwantung Army. Several, in fact, and one of them (the Imperial Way faction) attempted an actual coup d’etat in 1936. It was put down, and the Imperial Way faction dissolved (in theory), but the problem of an intensely ideologized officer corps remained. Long story short, you had a small group of highly ideologized officers garrisoning a remote province pulling the entire Empire into big, unwinnable wars.

One could make the case that World War II in the Pacific was ultimately caused by about fifteen or twenty guys in the Kwantung Army.

That’s overly reductionist, but it highlights the huge problem with organizations slipping the leash. In theory, there was a clear chain of command, and even the head of the Kwantung Army was a down it a ways — he was subordinate to the Army Council, which was subordinate to the War Minister, who was subordinate to the Parliament, who were subordinate to the Emperor. In theory, lots of people could’ve sacked Gen. Araki, or his mini-me Ishiwara Kanji (a lieutenant colonel through most of it). Equally in theory, Mantetsu had no say in any of it — the Kwantung Army was a formation of the Imperial Japanese Army, not Mantetsu’s private security force.

But in reality, Mantetsu was so wired in to the Japanese government that in a lot of cases, it was the government. But not always, because the same could be said about the Army, and the Navy, both of which were also wired into Mantetsu up to the very top (or vice versa, your choice). And Mantetsu had their Media arm, of course, as did the Army and Navy …

What all this boiled down to, then, was a power vacuum. I know, that seems weird, but a skilled bureaucratic infighter like Ishiwara never lacked for groups to play against each other. The Army and Navy would oppose on principle any move that seemed to aggrandize the other, neither could go against Mantetsu (and neither could control it), and all had to pay at least lip service to the civilian government. Because of this, real power fell to whomever had the balls to grab it …

… which was the officer corps of the Kwantung Army. They assassinated at least two Manchurian warlords, staged a number of false flag attacks on their own positions, and generally got up to however you say “standard issue Juggalo fuckery” in Japanese, up to and including a full-scale war with China.

Severian, “Slipping the Leash”, Founding Questions, 2022-08-27.

January 22, 2022

World War Zero – The Russo Japanese War

The Great War

Published 21 Jan 2022Get the Smartest Bundle in Streaming: https://smartbundle.com/thegreatwarsb

The Russo-Japanese War is nicknamed World War Zero – it was a clash between two world powers that foreshadowed war on an industrial scale as seen just 10 years later again. Gigantic land battles like the Battle of Mukden showed the true cost in manpower and materiel when modern armies clashed and the naval side of the war showed the strategic importance of modern navies.

» SUPPORT THE CHANNEL

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/thegreatwar» THANKS TO OUR CO-PRODUCERS

John Ozment, James Darcangelo, Jacob Carter Landt, Thomas Brendan, Kurt Gillies, Scott Deederly, John Belland, Adam Smith, Taylor Allen, Rustem Sharipov, Christoph Wolf, Simen Røste, Marcus Bondura, Ramon Rijkhoek, Theodore Patrick Shannon, Philip Schoffman, Avi Woolf,» BIBLIOGRAPHY

Akiyama Saneyuki, Gundan (Tokyo: Jitsugyō no Nihonsha, 1917)Atsuo Yokoyama; Toshikatsu Nishikawa & Ichō Konsōshiamu, Heishitachi ga mita Nichi-Ro sensō, (Tokyo: Yūzankaku, 2012)

Corbett, Julian S., Maritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905, Volume I, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2015)

Corbett, Julian S., Maritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905, Volume II, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2015)

Деникин А. И. Путь русского офицера. (Нью-Йорк: Изд. им. А. Чехова, 1953)

Forczyk, Robert, Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship: Yellow Sea 1904-05, (Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2009)

Hamby, Joel E, “Striking the Balance: Strategy and Force in the Russo-Japanese War” Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 30, No. 3 (2004)

Hosokawa Gentarō, Byōinsen Kōsai Maru kenbunroku (Tokyo: Hakubunkan Shinsha, 1993)

Ivanov, A & Jowett P, The Russo-Japanese War 1904-05, (Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2004)

Jacob, Frank, The Russo-Japanese War and its Shaping of the Twentieth Century, (London: Routledge, 2017)

Jukes, Geoffrey, The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905, (Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2014)

Kowner, Rotem (ed), Rethinking the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-5, Volume 1: Centennial Perspectives, (Folkestone: Global Oriental, 2007)

Lynch, George & Palmer, Frederick, In Many Wars By Many War Correspondnets, (Tokyo: Tokyo Printing Co. 1904)

Mozawa Yusaku, Aru hohei no Nichi-Ro Sensō jūgun nikki (Tokyo: Sōshisha, 2005)

Murakami Hyōe, Konoe Rentai ki (Tokyo: Akita Shoten, 1967)

Paine, S. C. M., The Japanese Empire: Grand Strategy from the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Steinberg, John W; Meaning, Bruce W; Schimmelpennick van der Oye, David; Wolff, David & Yokote, Shinji (eds.), The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective: World War Zero, (Leiden: Brill, 2005)

Stille, Mark, The Imperial Japanese Navy of the Russo-Japanese War, (Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2016)

Takagi Suiu, Jinsei hachimenkan (Tokyo: Teikoku Kyōiku Kenkyūkai, 1927)

van Dijk, Kees, Pacific Strife: The Great Powers and Their Political and Economic Rivalries in Asia and the Western Pacific, 1870-1914, (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015)

Warner, Denis & Warner, Peggy, The Tide at Sunrise: A History of the Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905, (London: Angus & Robertson, 1974)

»CREDITS

Presented by: Jesse Alexander

Written by: Jesse Alexander

Director: Toni Steller & Florian Wittig

Director of Photography: Toni Steller

Sound: Toni Steller

Editing: Jose Gamez

Motion Design: Philipp Appelt

Mixing, Mastering & Sound Design: http://above-zero.com

Research by: Jesse Alexander

Fact checking: Florian Wittig

Channel Design: Yves ThimianContains licensed material by getty images

All rights reserved – Real Time History GmbH 2022

October 12, 2021

Richard Overy looks at the “Great Imperial War” of 1931-1945

I missed Rana Mitter‘s review of Richard Overy’s latest book when it was published in The Critic last week:

Imagine there’s no Hitler. It’s not that easy, even if you try, at least if you’re a westerner thinking about the Second World War. But for millions of Asians, those years of conflict had little to do with the horrors of Nazi invasion and genocide, and it is their experience that frames Richard Overy’s account of a seemingly familiar conflict. For most non-Europeans, the war was not a struggle for democracy, but a conflict between empires, and in this book, that imperial struggle begins not with the invasion of Poland by Germany in 1939 but the occupation of Manchuria by the Japanese in 1931.

Blood and Ruins is really two books in one. The first is perhaps the single most comprehensive account of the Second World War yet to appear in one volume. You might think that by reading extensively, you could construct a book like this one. You could not — unless you have Overy’s control over a staggering range of World War II scholarship, much of it drawn from his own decades of research on the economics of total warfare, the development of technology, from radar to aerial bombing, and the idea of the “emotional geography” of war, encompassing morale, hope, and despair. Then you’d need to go back and cover all those categories for each of the major Allied and Axis belligerents: Britain, the US, Japan, Germany, France, Italy and China among them.

The second book is an argument about what kind of conflict the Second World War really was. Overy is clear: on a global as opposed to European scale, it was not (just) a war about democracy, but about empires and their fate, although “the starting point in explaining the pursuit of territorial empire is, paradoxically, the nation.”

Overy points out what is generally lost to view when the European war is placed at the centre of the historiography: both Britain and France were undertaking an “awkward double standard” in their defence of democratic values, as their Asian and African possessions “rested on a denial of those liberties and the repression of any protest against the undemocratic nature of colonial rule”. While this argument has been made before (not least by figures such as Nehru and Gandhi in India at the time), Overy does something unusual and revealing: he compares the western empires with Japan’s justification for its own imperial project in the early twentieth century.

The book is scrupulously careful not to endorse or excuse the worldview of Tokyo’s imperialists, and gives full weight to the voices of the Chinese nationalists and communists who were bitterly opposed to Japan’s expansion on the Asian mainland. Still, the comparison of Japan’s pre-war and wartime empire to those of the western powers provides an important and original broadening of a contemporary debate.

There is ongoing public British (and to some extent French) argument about whether empire was a “good” or “bad” thing. Yet neither attackers nor defenders of the British empire tend to analyse it alongside the Japanese equivalent that lasted nearly half a century. Britain committed colonial massacres (Amritsar) and deadly repression (Mau Mau). So did Japan (the rape of Nanjing, invasion of Manchuria).

Britain’s empire also created an aspirational middle class full of cosmopolitan nationalists, and drew on ideas of loyalty to recruit its subjects to fight in world wars. All these things are also true of Japan, which like Britain was a multi-party democracy for much of its period as an overseas empire (between 1898 and 1932), and whose capital city was an intellectual hub for political activists from across Asia.

As a colony of Japan between 1895-1945, Taiwan developed a middle class that was Japanese-speaking and keen to draw on new economic opportunities brought by empire: Lee Teng-hui, the first democratically elected president of the Republic of China on Taiwan, always thought of Japanese as his mother tongue. Park Chung-hee, the American-sponsored dictator of Cold War South Korea, learned his political craft as an army officer in the Japanese Manchukuo Army that occupied Manchuria.

July 13, 2021

Japanese Armour Doctrine, 1918-1942

The_Chieftain

Published 11 Jul 2021Sources include:

Japanese tanks and armoured Warfare 1932-45, David McCormack

WW2 Japanese Tank Tactics, Gordon Rottmen, Akira Takizawa

Japanese Tanks, Tactics and anti-tank weapons, Donald McLean

Type 89 and Tankette books, Kazunori YoshikawaContinuing on this series of videos supporting the WW2 Channel, I look at what I can find about how the Japanese thought of tanks and their usage, tempered by quite a bit of combat experience.

Improved-Computer-And-Scout Car Fund:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/The_Chieftain

Direct Paypal https://paypal.me/thechieftainshat

June 5, 2021

Battle of Khalkhin Gol 1939 – Soviet-Japanese War

Kings and Generals

Published 17 May 2020Our animated historical documentary series on modern warfare continues with a coverage of the Battles of Khalkin Gol of 1939, as the USSR and Japan clashed in Mongolia and Manchuria. Although this short war didn’t change much in the Far East, it played a huge role during World War II.

Cold War channel: http://bit.ly/2UHebLI

Modern Warfare series: http://bit.ly/2W2SeXFSupport us on Patreon: http://www.patreon.com/KingsandGenerals or Paypal: http://paypal.me/kingsandgenerals

We are grateful to our patrons and sponsors, who made this video possible: https://docs.google.com/document/d/17…

The video was made by Leif Sick, while the script was developed by Ivan Moran

This video was narrated by Officially Devin (https://www.youtube.com/user/OfficiallyDevin)

✔ Merch store ► teespring.com/stores/kingsandgenerals

✔ Podcast ► Google Play: http://bit.ly/2QDF7y0 iTunes: https://apple.co/2QTuMNG

✔ Twitter ► https://twitter.com/KingsGenerals

✔ Instagram ► http://www.instagram.com/Kings_GeneralsProduction Music courtesy of Epidemic Sound: http://www.epidemicsound.com

#Documentary #KhalkinGol #WorldWar2

March 4, 2020

Resistance in China – Myth or Reality? – WW2 – War Against Humanity 009

World War Two

Published 3 Mar 2020The war in China already started in 1931 when Japan invaded Manchuria. Early resistance was small and was met by heavy Japanese retaliations. But throughout the 30’s, the movement started to grow.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Join our Discord Server: https://discord.gg/D6D2aYN.

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesHosted by: Spartacus Olsson

Written by: Francis van Berkel

Produced and Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Francis van Berkel

Edited by: Mikołaj Cackowski

Map animations: Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Colorizations by:

Norman Stewart – https://oldtimesincolor.blogspot.com/Sources:

Library of Congress

Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

Chinese anti-Japanese posters, courtesy of pictoright

SHANGHAI, CHINA-1921Soundtracks from the Epidemic Sound:

Johan Hynynen – “Dark Beginning”

Yi Nantiro – “Watchmen”

Yi Nantiro – “A Single Grain of Rice”

Reynard Seidel – “Deflection”

Fabien Tell – “Last Point of Safe Return”

Andreas Jamsheree – “Guilty Shadows 4”

Rannar Sillard – “Split Decision”Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

February 7, 2020

Did WW2 Start in 1937? – The Rape of China | BETWEEN 2 WARS I 1937 Part 1 of 2

TimeGhost History

Published 6 Feb 20201937 marks the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War. And whether or not this is the “actual” starting point of World War Two, it definitely was a devastating conflict which led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands and the displacement of millions.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Subscribe to our World War Two series: https://www.youtube.com/c/worldwartwo…

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Francis van Berkel

Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Francis van Berkel

Edited by: Daniel Weiss

Sound design: Marek Kaminski

Research and Writing Assistance: Rune Vaever HartvigSources:

Photo of Shanghai 1932. from 2013 Adrienne Livesey, Elaine Ryder and Irene BrienColorizations by Daniel Weiss

Soundtracks from Epidemic Sound:

– “The Beast” – Dream Cave

– “Split Decision” – Rannar Sillard

– “March Of The Brave 10” – Rannar Sillard – Test

– “Disciples of Sun Tzu” – Christian Andersen

– “The Inspector 4” – Johannes Bornlöf

– “Death And Glory 1” – Johannes Bornlöf

– “Magnificent March 3” – Johannes Bornlöf

– “Trapped in a Maze” – Philip Ayers

– “Last Man Standing 3” – Johannes Bornlöf

– “Not Safe Yet” – Gunnar Johnsen

– “Under the Dome” – Philip Ayers

– “First Responders” – Skrya

– “The Charleston 3” – Håkan ErikssonA TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

1 day ago (edited)

Okay, so we’re not actually telling you unequivocally that World War Two started in 1937. Technically things only got global when the European powers became involved with the backing of their colonies (and in Britain’s case, the Commonwealth). What we are trying to tell you here is that how you periodize or define a historical event depends on whose perspective you are writing from. The people of Eastern Asia experienced World War Two as the progressive escalation from 1937 (or even 1931), to 1941, to 1945. In the same way the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 marks for many in Europe the outbreak of war, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in July 1937 marks for many in Eastern Asia the start of the very same event. Let us know what you think of this in the comments. Does it make you think differently about the war?

Cheers, Francis.

September 4, 2019

Japan, the Bureaucratic War Machine | BETWEEN 2 WARS I 1931 Part 2 of 3

TimeGhost History

Published on 3 Sep 2019In Japan there has been a gradual increase of militarism since the Great War and in 1931 the country goes to war again when they invade Chinese Manchuria based on a false flag terrorist strike at the Mukden railway junction.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Subscribe to our World War Two series: https://www.youtube.com/c/worldwartwo…

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Spartacus Olsson

Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Joram Appel and Spartacus Olsson

Edited by: Danile Weiss

Sound design: Marek KaminskySources:

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

Sources:

James Fulcher, The Bureaucratization of the State and the Rise of Japan (1988)

Katō Yōko, “The debate on fascism in Japanese historiography”, in: Sven Saaler and Christopher W.A. Szpilman (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese History (2018), 225-236.

Ethan Mark, “Japan’s 1930s crisis, fascism, and social imperialism”, in: Sven Saaler and Christopher W.A. Szpilman (ed)., Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese History (2018), 237-250.

Penolepe Francks, “The path of economic development from the late nineteenth centre to the economic miracle”, in: Sven Saaler and Christopher W.A. Szpilman (ed)., Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese History (2018), 267-278.

Sandra Wilson and Robert Cribb, “Japan’s colonial empire”, in: Sven Saaler and Christopher W.A. Szpilman (ed)., Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese History (2018), 77-91.

Mark R. Peattie, “Nanshin: The ‘Southward Advance’, 1931-1941, as a Prelude to the Japanese Occupation of Southeast Asia”, in: Peter Duus e.a., The Japanese Wartime Empire, 1931-1945 (2010), 190-242.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

13 minutes ago

This is the third of several episodes that cover the developments in East Asia leading to World War Two. In this episode we look at how Japan by 1931 has developed to be on the brink of a fascist state without anyone specifically taking power or staging a coup. The democratic reforms from the past four decades are dying a death by a thousand cuts as the Japanese administration and military simply take one small decision after the other that erodes freedom, dials back democracy, and inevitably leads to war. It’s an anonymous, mechanic, gradual movement towards global conflict proceeding with clockwork precision.This episode also sees the first change to the Between 2 Wars set as Astrid and Wieke have started adapting the set to the changing themes, while we move closer and closer to the outbreak of WW2 — we’d love to hear what you think!