Back around the turn of the 20th century, the Russians decided to build a railroad across Siberia, the better to (among other things) supply their spiffy new naval base at Port Arthur, on the strategic Liaodong Peninsula (linking up with their Chinese Eastern Railway). This pissed off the Japanese, who claimed the Peninsula by right of conquest in the First Sino-Japanese War. Unpleasantness ensued.

Further unpleasantness ensued in the wake of World War I, when both Imperial Russia and Republican China collapsed. The Japanese had a big railroad project of their own going in the Kwantung Leased Territory, which was threatened by the chaos. Moreover, the big Japanese railroad project had grown — as Japanese industrial concerns tend to do — into a ginormous, all-encompassing combine known as Mantetsu.

So far, so recondite, I suppose, but stop me if this part sounds familiar: Mantetsu was so big, and so shady, that it was all but impossible to tell where “the guys running Mantetsu” ended and “the Japanese government” began. And it gets better: Thanks to the Japanese Empire’s distinctive (to put it mildly, and kindly) administrative structure, it was equally hard to tell where “the Japanese government” ended and “the Japanese military” began. Even better — by which I mean much, much worse, but again feel free to stop me when this sounds familiar — “the Japanese military” was itself composed of several wildly different, mutually hostile chains of command, all competing with each other for political power, economic access, and glory. Best of all — by which, again, I mean worst — since Mantetsu was so big, and so wired-in to every level of the Japanese government, it basically got its own army, which was effectively separate even from the Army High Command back in Tokyo.

Here again, the granular details are insanely complex, and I’m not qualified to walk you through them, but the upshot is: Thanks to all of the above, plus the active enmity of the rapidly-rearming Soviet Union and the rapidly-accelerating chaos of the Warlord Period in China, Japan’s foreign policy ended up being dictated by the Kwantung Army, with almost no reference to even the High Command, let alone the civilian politicians, back in Tokyo. A particular warlord giving the Mantetsu Board of Directors — or, you know, whoever — grief? No problem — boom! Oh, that didn’t solve the problem, and now the politicians are dragging their feet? Might as well blow up a different part of your own railway, seize a whole bunch of territory on that flimsy pretext, and set up a puppet government to give you cover …

I don’t expect y’all to follow all the links right away, so trust me on this: Nobody involved in any of that stuff ranked higher than colonel. Indeed, the guy most “responsible” — if that’s really the word — for all of this stuff was a staff pogue, also a colonel, named Kanji Ishiwara. He and another staff pogue, Seishiro Itagaki, who was head of the Kwantung Army’s intelligence section, orchestrated the Japanese invasion of China, and while it’s oversimplifying things a bit too much to say those two clowns started World War II in the Pacific, I’m not stopping you from saying it.

From there, events took on a logic of their own. The rest of the Army was soon committed to the war in North China, which rapidly became the war in all the rest of China. The Navy, not wanting to let the Army hog all the glory, had gotten in on the war a few years prior to the Marco Polo Bridge, and soon enough they were causing all kinds of international grief on their own account. Put simply, but not unfairly, you had the Navy chasing the Army, and the Army chasing itself, all across China, with the civilian politicians lagging way behind in the rear, desperately trying to catch up, or even just figure out what the hell was going on …

Severian, “Lessons from Manchuria”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-04-21.

February 10, 2024

QotD: When Manchuria became Manchukuo

May 13, 2022

Battle of Tsushima – When the 2nd Pacific Squadron thought it couldn’t get any worse…

Drachinifel

Published 18 Sep 2019At long last the 2nd Pacific Squadron’s voyage comes to an end …

Want to support the channel? – https://www.patreon.com/Drachinifel

Want a shirt/mug/hoodie – https://shop.spreadshirt.com/drachini…

Want a medal? – https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/Drachinifel

Want to talk about ships? https://discord.gg/TYu88mt

Want to get some books? www.amazon.co.uk/shop/drachinifel

Drydock Episodes in podcast format – https://soundcloud.com/user-21912004

January 22, 2022

World War Zero – The Russo Japanese War

The Great War

Published 21 Jan 2022Get the Smartest Bundle in Streaming: https://smartbundle.com/thegreatwarsb

The Russo-Japanese War is nicknamed World War Zero – it was a clash between two world powers that foreshadowed war on an industrial scale as seen just 10 years later again. Gigantic land battles like the Battle of Mukden showed the true cost in manpower and materiel when modern armies clashed and the naval side of the war showed the strategic importance of modern navies.

» SUPPORT THE CHANNEL

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/thegreatwar» THANKS TO OUR CO-PRODUCERS

John Ozment, James Darcangelo, Jacob Carter Landt, Thomas Brendan, Kurt Gillies, Scott Deederly, John Belland, Adam Smith, Taylor Allen, Rustem Sharipov, Christoph Wolf, Simen Røste, Marcus Bondura, Ramon Rijkhoek, Theodore Patrick Shannon, Philip Schoffman, Avi Woolf,» BIBLIOGRAPHY

Akiyama Saneyuki, Gundan (Tokyo: Jitsugyō no Nihonsha, 1917)Atsuo Yokoyama; Toshikatsu Nishikawa & Ichō Konsōshiamu, Heishitachi ga mita Nichi-Ro sensō, (Tokyo: Yūzankaku, 2012)

Corbett, Julian S., Maritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905, Volume I, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2015)

Corbett, Julian S., Maritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905, Volume II, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2015)

Деникин А. И. Путь русского офицера. (Нью-Йорк: Изд. им. А. Чехова, 1953)

Forczyk, Robert, Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship: Yellow Sea 1904-05, (Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2009)

Hamby, Joel E, “Striking the Balance: Strategy and Force in the Russo-Japanese War” Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 30, No. 3 (2004)

Hosokawa Gentarō, Byōinsen Kōsai Maru kenbunroku (Tokyo: Hakubunkan Shinsha, 1993)

Ivanov, A & Jowett P, The Russo-Japanese War 1904-05, (Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2004)

Jacob, Frank, The Russo-Japanese War and its Shaping of the Twentieth Century, (London: Routledge, 2017)

Jukes, Geoffrey, The Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905, (Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2014)

Kowner, Rotem (ed), Rethinking the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-5, Volume 1: Centennial Perspectives, (Folkestone: Global Oriental, 2007)

Lynch, George & Palmer, Frederick, In Many Wars By Many War Correspondnets, (Tokyo: Tokyo Printing Co. 1904)

Mozawa Yusaku, Aru hohei no Nichi-Ro Sensō jūgun nikki (Tokyo: Sōshisha, 2005)

Murakami Hyōe, Konoe Rentai ki (Tokyo: Akita Shoten, 1967)

Paine, S. C. M., The Japanese Empire: Grand Strategy from the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Steinberg, John W; Meaning, Bruce W; Schimmelpennick van der Oye, David; Wolff, David & Yokote, Shinji (eds.), The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective: World War Zero, (Leiden: Brill, 2005)

Stille, Mark, The Imperial Japanese Navy of the Russo-Japanese War, (Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2016)

Takagi Suiu, Jinsei hachimenkan (Tokyo: Teikoku Kyōiku Kenkyūkai, 1927)

van Dijk, Kees, Pacific Strife: The Great Powers and Their Political and Economic Rivalries in Asia and the Western Pacific, 1870-1914, (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015)

Warner, Denis & Warner, Peggy, The Tide at Sunrise: A History of the Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905, (London: Angus & Robertson, 1974)

»CREDITS

Presented by: Jesse Alexander

Written by: Jesse Alexander

Director: Toni Steller & Florian Wittig

Director of Photography: Toni Steller

Sound: Toni Steller

Editing: Jose Gamez

Motion Design: Philipp Appelt

Mixing, Mastering & Sound Design: http://above-zero.com

Research by: Jesse Alexander

Fact checking: Florian Wittig

Channel Design: Yves ThimianContains licensed material by getty images

All rights reserved – Real Time History GmbH 2022

October 1, 2021

The Russian 2nd Pacific Squadron – Voyage of the Damned

Drachinifel

Published 13 Mar 2019The story of a few good men’s struggle, against their own commanders, their own fleet, their own ships and their own men.

Want to support the channel? – https://www.patreon.com/Drachinifel

Want to talk about ships? https://discord.gg/TYu88mt

August 28, 2021

Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905 – Battle of Tsushima

Kings and Generals

Published 16 Dec 2018In our new historical animated documentary, we will cover the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 with a focus on the naval engagements at Tsushima, the Yellow Sea, and Port Arthur. This conflict between Russia and Japan was unique due to the heavy usage of the battleships and its results influenced the First and Second World Wars.

Support us on Patreon: http://www.patreon.com/KingsandGenerals or Paypal: http://paypal.me/kingsandgenerals

Check out our Merch Store: teespring.com/stores/kingsandgenerals

We are grateful to our patrons and youtube members, who made this video possible: https://drive.google.com/open?id=1Tff…

This video was narrated by Officially Devin (https://www.youtube.com/user/OfficiallyDevin)

✔ Merch store ► teespring.com/stores/kingsandgenerals

✔ Podcast ► Google Play: http://bit.ly/2QDF7y0 iTunes: https://apple.co/2QTuMNG

✔ Twitter ► https://twitter.com/KingsGenerals

✔ Instagram ► http://www.instagram.com/Kings_GeneralsSources:

Robert Forczyk – Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship

William Koenig – Epic Sea Battles

Левицкий – Русско-японская война 1904—1905

Сорокин – Оборона Порт-Артура. Русско-японская война 1904—1905Production Music courtesy of Epidemic Sound: http://www.epidemicsound.com

#Documentary #RussoJapaneseWar #KingsAndGenerals

February 25, 2018

Feature History – Russo-Japanese War

Feature History

Published on 28 May 2017Hello and welcome to Feature History, featuring a Russian and Japanese disagreement, and why you don’t record when sick.

October 8, 2014

Russia’s oldest warship being moved to shipyard for restoration work

From the Wikipedia page:

Aurora (Russian: Авро́ра, tr. Avrora; IPA: [ɐˈvrorə]) is a 1900 Russian protected cruiser, currently preserved as a museum ship in St. Petersburg. Aurora was one of three Pallada-class cruisers, built in St. Petersburg for service in the Pacific Far East. All three ships of this class served during the Russo-Japanese War. The Aurora survived the Battle of Tsushima and was interned under U.S. protection in the Philippines, eventually returned to the Baltic Fleet. The second ship, Pallada, was sunk by the Japanese at Port Arthur in 1904. The third ship, Diana, was interned in Saigon after the Battle of the Yellow Sea. One of the first incidents of the October Revolution in Russia took place on the cruiser Aurora.

[…]

During World War I Aurora operated in the Baltic Sea performing patrols and shore bombardment tasks. In 1915, her armament was changed to fourteen 152 mm (6 in) guns. At the end of 1916, she was moved to Petrograd (the renamed St Petersburg) for a major repair. The city was brimming with revolutionary ferment and part of her crew joined the 1917 February Revolution. A revolutionary committee was created on the ship, with Aleksandr Belyshev elected as captain. Most of the crew joined the Bolsheviks, who were preparing for a Communist revolution.

At 9.45 p.m on 25 October 1917 (O.S.) a blank shot from her forecastle gun signaled the start of the assault on the Winter Palace, which was to be the beginning of the October Revolution. In summer 1918, she was relocated to Kronstadt and placed into reserve.

August 5, 2014

Who is to blame for the outbreak of World War One? (Part seven of a series)

I thought we’d be done by now, but there’s still more historical ground to cover on what I think are the deep origins of the First World War (part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, part six). The previous post examined the naval arms race between Britain and Germany. Today, we’re looking at the unhappy Russian experiences in the far East and the dangerous domestic situation it faced after the war.

Russia’s Oriental catastrophe

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 was a huge upset, as all the great powers expected Russia to crush the upstart Japanese and put them back “in their place”. Japan’s stunning naval and military successes at the Battle of the Yellow Sea, Tsushima and Port Arthur left Russia in a potentially disastrous situation, with utter undeniable defeat in the East and revolution brewing at home.

The war came about due to irreconcilable differences in the expansionary plans of the two empires: Russia wanted control of Manchuria and Japan wanted control of Korea, but neither side trusted the other enough to make negotiations work. Japan decided to initiate the conflict with a surprise attack on the Russian naval forces in Port Arthur (now known as the Lüshunkou District of Dalian in China’s Liaoning province). From that point onwards, Japan maintained the initiative, forcing Russia to react and interrupting Russian moves on land and at sea.

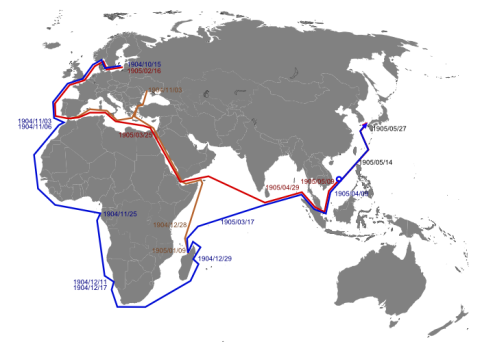

After the defeat of the original Russian fleet in the Pacific, the Baltic Fleet was re-tasked and set out to avenge the loss. The fleet’s luck was terrible to begin with, as shortly after passing between Sweden and Denmark and sailing out into the North Sea, lookouts on the Russian battleships spotted Japanese forces and the fleet opened fire. Twenty minutes, later the enemy was in tatters … unfortunately, the “enemy” were British fishing trawlers. Given the massive firepower of even pre-dreadnought ships, the casualties were surprisingly light: one trawler sunk, two dead, and many wounded. Not long afterward, a Russian ship in the fleet was mis-identified as a Japanese ship and nearly sunk by friendly fire. The nearest Japanese ship was still thousands of miles to the East.Despite nearly starting a war with the Royal Navy over the Dogger Bank incident (Britain and Japan had signed an alliance in 1902), Admiral Rozhdestvensky was unapologetic and insisted it was the trawlers’ fault and his ships were perfectly entitled to defend themselves from Japanese attackers. As a result of the Russian mistake, Britain refused to allow the fleet passage through the Suez Canal, forcing them to take the far longer trip around Africa instead. If ever a military expedition has had bad omens, the sortie of the Baltic Fleet — now renamed the Second Pacific Squadron for this mission — must be one of the best examples.

When the Russian and Japanese fleets met in the Tsushima Straits, Admiral Tōgō managed to “cross the T” of the Russians, allowing his ships to use their full broadside armament against only the forward-facing guns of the Russian ships. In the end, the Second Pacific Squadron lost all eleven battleships and over 4,000 men killed, another 5,900 captured, and 1,800 interned. Japanese losses were trivial in comparison: three torpedo boats sunk, 117 men killed and about 500 wounded.

There were no major subsequent battles, and Russia was forced to sign the Treaty of Portsmouth to end the war in September 1905. Despite the Tsar’s initial instructions to the Russian delegation, the Russians agreed to recognize Japan’s sphere of influence in Korea, withdraw their troops from Manchuria, and to give up their lease on Port Arthur and Talien. The reaction in both countries was similar: political unrest. Japanese public opinion was that they had been cheated of their full reward from the war, and the government fell in the aftermath. Russians were even more angry and the result was revolution.

The (first) Russian revolution

While the result of the Russo-Japanese war was the trigger for the 1905 Revolution, it was far from being the only grievance. Margaret MacMillan wrote in The War That Ended Peace:

In 1904 the Minister of the Interior, Vyacheslav Plehve, is reported to have said that Russia needed “a small victorious war” which would take the minds of the Russian masses off “political questions”.

The Russo-Japanese War showed the folly of that idea. In its early months Plehve himself was blown apart by a bomb; towards its end the newly formed Bolsheviks tried to seize Moscow. The war served to deepen and bring into sharp focus the existing unhappiness of many Russians with their own society and its rulers. As the many deficiencies, from command to supplies, of the Russian war effort became apparent, criticism grew, both of the government and, since the regime was a highly personalized one, of the Tsar himself. In St. Petersburg a cartoon showed the Tsar with his breeches down being beaten while he says, “Leave me alone. I am the autocrat!” Like the French Revolution, with which it had many similarities, the Russian Revolution of 1905 broke old taboos, including the reverence surrounding the country’s ruler. It seemed to officials in St. Petersburg a bad omen that the Empress had hung a portrait of Marie Antoinette, a gift from the French government, in her rooms.

In December 1904, a strike in St. Petersburg triggered sympathy strikes in other industries, leading to 80,000 workers and supporters protesting in the city. In January 1905, a mass march by the strikers to the Winter Palace was met with rifle fire from the defending troops. Casualty estimates range from 200 to over 1,000 on Bloody Sunday. The strikes and protests spread beyond St. Petersburg, to the point that the government was threatened. Eventually the Tsar was persuaded to offer concessions :

Under huge pressure from his own supporters, the Tsar reluctantly issued a manifesto in October promising a responsible legislature, the Duma, as well as civil rights.

As so often happens in revolutionary moments, the concessions only encouraged the opponents of the regime. It appeared to be close to collapsing with its officials confused and ineffective in the face of such widespread disorder. That winter a battalion from Nichlas’s own regiment, the Preobrazhensky Guards, which had been founded by Peter the Great, mutinied. A member of the Tsar’s court wrote in his diary: “This is it.” Fortunately for the regime, its most determined enemies were disunited and not yet ready to take power while moderate reformers were prepared to support it in the light of the Tsar’s promises. Using the army and police freely, the government managed to restore order. By the summer of 1906 the worst was over — for the time being. The regime still faced the dilemma, though, of how far it could let reforms go without fatally undermining its authority. It was a dilemma faced by the French government in 1789 or the Shah’s government in Iran in 1979. Refusing demands for reform and relying on repression creates enemies; giving way encourages them and brings more demands.

Russia’s economy did recover eventually, but the political solution was not strong enough to stand the strains of another war any time soon. In some ways, it’s hard to imagine what the Russian leaders who advised the Tsar were thinking as the Russians continued to stir the pot in the Balkans…