We’ve introduced this problem before but we should do so again in more depth. Logistics in modern armies is rather unlike logistics in pre-modern armies; to be exact the break-point here is the development of the railroad. Once armies can be supplied with railroads, their needs shift substantially. In particular, modern armies with rail (or later, truck and air) supply can receive massively more supplies over long distance than pre-railroad armies. That doesn’t make modern logistics trivial, rather armies “consumed” that additional supply by adopting material intensive modes of warfare: machine guns and artillery fire a lot of rounds that need to be shipped from factories to the front while tanks and trucks require a lot of fuel and spare parts. Basics like food and water were no less necessary but became a smaller share of much, much larger logistics chains that are dominated by ammunition and fuel.

But in the pre-railroad era (note: including the early gunpowder era well into the 1800s) that wasn’t the case. Soldiers could carry their own weapons and often their own ammunition (which in turn put significant limits on both). For handheld weapons, the difference gunpowder made here was fairly limited, since muskets were fairly slow firing and soldiers had to carry the ammunition they’d have for a battle in any event. The major difference with gunpowder came with artillery (that is, cannon), which needed the cannon, their powder and shot all moved. The result was a substantial expansion of the “siege train” of the army, which did not change the structure of logistics but did place new and heavy demands on it, because the animals and humans moving all of that needed to be fed. But overwhelming all of that was food and, if necessary, water.

Adult men need anywhere from 2,000 to 3,200 calories per day in order to support their activity; soldiers marching under heavy load will naturally tend towards the higher end of this range. Now, these requirements can be fudged; as John Landers notes, soldiers who are underfed do not immediately shut off. On the other hand, they cannot be ignored for long: no matter the morale an undernourished army will struggle to perform. Starvation is real and does not care how many reps you could do or how motivated you were when the campaign started (in practice, armies that are not fed sufficiently dissolve away as men desert rather than starve).

Different armies and different cultures will meet that nutritional demand in different ways, but staple grains (wheat, barley, corn, rice) dominate rations in part because they also dominated the diet of the peasantry (being the highest calories-per-acre-farmed-and-labor-added foods) and because they were easy to move and store. Fruits and vegetables were, by contrast, always subject to local availability, since without refrigeration they were difficult to keep or move; meat at least could be smoked, salted or made into jerky, but its expense made it an optional bonus to the diet rather than the core of it. So the diet here is mostly bread; many armies reliant on wheat and barley agriculture came up with a fairly similar idea here: a dense but simple flour-and-water (and maybe salt) biscuit or cracker which if kept dry could keep for long periods and be easy to move. The Romans called this buccelatum; today we refer to a very similar modern idea as “hardtack“. However, because these biscuits aren’t very tasty, for morale reasons armies try to acquire actual bread where possible.

In practice the combination of calorie demands with calorie-dense grain-based foods is going to mean that rations tend to cluster in terms of weight, even from different armies. Spartan rations on Sphacteria were two choenikes of barley alphita (a course barley flour) per man per day (Thuc. 4.16.1) which comes out to roughly 1.4kg; Spartan grain contributions to the syssitia (Plut. Lyc. 12.2) were 1 medimnos of barley alphita per month, which comes out to almost exactly 1kg per day (but supplemented with meat and such). Both Roth and Erdkamp (op. cit. for both) try to calculate the weight of Roman rations based on reported grain rations and interpolations for other foodstuffs; Roth suggests a range of 1.1-1.327kg (of which .85kg was grain or bread), while Erdkamp simply notes that they must have been somewhat more than the .85kg grain ration minimum.1 The Army of Flanders was given pan de munición (“munition” or “ration” bread) made of a mix of wheat and rye in loaves of standard size; the absolute minimum ration was 1.5lbs (.68kg) per day (Parker, op. cit. 136), somewhat less than the more logistically capable (as we’ll see) Roman legions, but in the ballpark, especially when we remember that soldiers in the Army of Flanders often supplemented that with purchased or pillaged food. Daily U.S. Army rations during the American Civil War were around 3lbs (1.36kg; statistic via Engels (op. cit.) who inexplicably thinks this is a useful reference for Macedonian rations), but some of the things included (particularly the 1.6oz of coffee) were hardly minimum necessities; the United States much like the Romans has a well-earned reputation for better than average rations, though this is admittedly a low bar.

So we can see a pretty tight grouping here around 1kg, especially when we account for some of these ration-packages being supplemented by irregular but meaningful amounts of other foods (especially in the case of the Army of Flanders, where we know this happened). There is some wiggle room here, of course; marching rations like hardtack are going to be lighter per-day than raw grains or good bread (or other, even tastier foods). But once meat, vegetables and fruits – and the diet must be at least sometimes supplemented with non-grain foods for nutritional reasons – are accounted for, you can see how the rule of thumb around 3lbs or 1.36kg forms out of the evidence. Soldiers also need around three liters of water (which is 3kg, God bless the metric system) per day but we are going to operate on the hopeful assumption that water is generally available on the route of our march. If it isn’t our daily load jumps from 1.36kg to 4.36kg and our operational range collapses into basically nothing; in practice this meant that if local water wasn’t available an army simply couldn’t go there.2

Marching loads vary by army and period but generally within a range of 40 to 55kg or so (60 at the absolute upper-end). As you may well imagine, convincing soldiers to carry heavier loads demands a greater degree of discipline and command control, so while a general may well want to push soldier’s marching load up, the soldiers will want to push it down (and of course overloading soldiers is going to eventually have a negative impact on marching speed and movement capabilities). But you may well be thinking that 40-55kg (which is 90-120lbs or so) sounds more than ample – that’s a lot of food!

Except of course they need to carry everything and weapons, armor and (for gunpowder armies) shot are heavy. Roman soldiers were and are famous for having marched heavy, carrying as much of their equipment and supplies as possible in their packs, which the Romans called the sarcina (we’ll see why this could improve an army’s capabilities). This practice is often attributed to Gaius Marius in the last decade of the second century (Plut. Marius 13.1) but care is necessary as this sort of “reform” was a trope of Roman generalship and is used of even earlier generals than Marius (e.g. Plut. Mor. 201BC on Scipio Aemilianus). Various estimates for the marching load of Roman troops exist but the best is probably Marcus Junkelmann’s physical reconstruction (in Die Legionen des Augustus (1986); highly recommended if you can read German; alas for the lack of an English translation!) which recreated all of the Roman kit and measured a marching load of 54.8kg (120.8lbs), with ~43 of the 54.8kg reserved for weapons, armor, entrenching kit and personal equipment, leaving just 11.8kg for food (about ten days worth). Other estimates are somewhat less, but never much less than 40kg for a Roman soldier’s equipment before rations, leaving precious little weight in which to fit a lot of food.

The same exercise can be run for almost any kind of infantryman: while their load is often heavy, after one accounts for weapons, armor and equipment (and for later armies, powder and shot) there is typically little space left for rations, usually amounting to not more than a week or two (ten days is a normal rule of thumb). Since the army obviously has more than two weeks of work to do (and remember it needs to be able to march back to wherever it started at the end), it is going to need to get a lot more food.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Logistics, How Did They Do It, Part I: The Problem”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-07-15.

1. To be clear, we know with some certainty that Roman rations were supplemented, but not by how much. If you read much older scholarship, you will find the notion that Roman soldier’s diet lacked regular meat; both Erdkamp and Roth reject this view decisively and for good reason.

2. I may return to the logistics of water later, but some range can be extended here by taking advantage of the fact that pack animals, while they need a lot of water per day over a long period, can be marched short periods with basically no water and still function, whereas water deprived humans die very quickly. Consequently an army can do a low-water “lunge” over short distances by loading its pack animals with water, not watering them, having the soldiers drink the water and then abandoning the pack animals as they die (the water they carried having been consumed). This is, to say it least, a very expensive thing to do – animals are not cheap! – but there is some evidence the Romans did this, on this see G. Moss, “Watering the Roman Legion” M.A. Thesis, UNC Chapel Hill (2015).

April 6, 2025

QotD: The basics of army logistics before railways

March 9, 2025

Italy’s Italian Fiasco

World War Two

Published 8 Mar 2025Today Sebastian puts Indy and Sparty in the hot seat for questions about the war in China and North Africa. Just what is the deal with the Italian Army anyway? How much fighting did the CCP do against the Japanese? And what’s the most overlooked event of the first year of war?

(more…)

January 20, 2025

Campo-Giro M1913 – Spain’s First Domestic Selfloader

Forgotten Weapons

Published 31 May 2015The Campo-Giro was Spain’s first indigenous self-loading military pistol, adopted in 1912 to replace the Belgian 1908 Bergmann-Mars. Only a small number were made of the original M1913 variety, with the vast majority being the later and slightly more refined M1913/16. This particular example is an early one, and particularly interesting to look at for that reason. The gun is a straight blowback design in 9mm Largo, and only lasted as Spain’s standard pistol until its descendent, the Astra 400, was adopted in 1921.

November 17, 2024

Three (more) Forgotten Roman Megaprojects

toldinstone

Published Jul 19, 2024This video explores another three forgotten Roman megaprojects: the colossal gold mines at Las Médulas, Spain; the Anastasian Wall, Constantinople’s outer defense; and Rome’s artificial harbor at Portus.

Chapters:

0:00 Las Médulas

3:13 The Anastasian Wall

5:24 Portus

(more…)

October 11, 2024

QotD: Fascists are inherently bad at war

For this week’s musing, I wanted to take the opportunity to expand a bit on a topic that I raised on Twitter which draw a fair bit of commentary: that fascists and fascist governments, despite their positioning are generally bad at war. And let me note at the outset, I am using fascist fairly narrowly – I generally follow Umberto Eco’s definition (from “Ur Fascism” (1995)). Consequently, not all authoritarian or even right-authoritarian governments are fascist (but many are). Fascist has to mean something more specific than “people I disagree with” to be a useful term (mostly, of course, useful as a warning).

First, I want to explain why I think this is a point worth making. For the most part, when we critique fascism (and other authoritarian ideologies), we focus on the inability of these ideologies to deliver on the things we – the (I hope) non-fascists – value, like liberty, prosperity, stability and peace. The problem is that the folks who might be beguiled by authoritarian ideologies are at risk precisely because they do not value those things – or at least, do not realize how much they value those things and won’t until they are gone. That is, of course, its own moral failing, but society as a whole benefits from having fewer fascists, so the exercise of deflating the appeal of fascism retains value for our sake, rather than for the sake of the would-be fascists (though they benefit as well, as it is, in fact, bad for you to be a fascist).

But war, war is something fascists value intensely because the beating heart of fascist ideology is a desire to prove heroic masculinity in the crucible of violent conflict (arising out of deep insecurity, generally). Or as Eco puts it, “For Ur-Fascism there is no struggle for life, but, rather, life is lived for struggle … life is permanent warfare” and as a result, “everyone is educated to become a hero“. Being good at war is fundamentally central to fascism in nearly all of its forms – indeed, I’d argue nothing is so central. Consequently, there is real value in showing that fascism is, in fact, bad at war, which it is.

Now how do we assess if a state is “good” at war? The great temptation here is to look at inputs: who has the best equipment, the “best” soldiers (good luck assessing that), the most “strategic geniuses” and so on. But war is not a baseball game. No one cares about your RBI or On-Base percentage. If a country’s soldiers fight marvelously in a way that guarantees the destruction of their state and the total annihilation of their people, no one will sing their praises – indeed, no one will be left alive to do so.

Instead, war is an activity judged purely on outcomes, by which we mean strategic outcomes. Being “good at war” means securing desired strategic outcomes or at least avoiding undesirable ones. There is, after all, something to be said for a country which manages to salvage a draw from a disadvantageous war (especially one it did not start) rather than total defeat, just as much as a country that conquers. Meanwhile, failure in wars of choice – that is, wars a state starts which it could have equally chosen not to start – are more damning than failures in wars of necessity. And the most fundamental strategic objective of every state or polity is to survive, so the failure to ensure that basic outcome is a severe failure indeed.

Judged by that metric, fascist governments are terrible at war. There haven’t been all that many fascist governments, historically speaking and a shocking percentage of them started wars of choice which resulted in the absolute destruction of their regime and state, the worst possible strategic outcome. Most long-standing states have been to war many times, winning sometimes and losing sometimes, but generally able to preserve the existence of their state even in defeat. At this basic task, however, fascist states usually fail.

The rejoinder to this is to argue that, “well, yes, but they were outnumbered, they were outproduced, they were ganged up on” – in the most absurd example, folks quite literally argued that the Nazis at least had a positive k:d (kill-to-death ratio) like this was a game of Call of Duty. But war is not a game – no one cares what your KDA is if you lose and your state is extinguished. All that matters is strategic outcomes: war is fought for no other purpose because war is an extension of policy (drink!). Creating situations – and fascist governments regularly created such situations. Starting a war in which you will be outnumbered, ganged up on, outproduced and then smashed flat: that is being bad at war.

Countries, governments and ideologies which are good at war do not voluntarily start unwinnable wars.

So how do fascist governments do at war? Terribly. The two most clear-cut examples of fascist governments, the ones most everyone agrees on, are of course Mussolini’s fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Fascist Italy started a number of colonial wars, most notably the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, which it won, but at ruinous cost, leading it to fall into a decidedly junior position behind Germany. Mussolini then opted by choice to join WWII, leading to the destruction of his regime, his state, its monarchy and the loss of his life; he managed to destroy Italy in just 22 years. This is, by the standards of regimes, abjectly terrible.

Nazi Germany’s record manages to somehow be worse. Hitler comes to power in 1933, precipitates WWII (in Europe) in 1939 and leads his country to annihilation by 1945, just 12 years. In short, Nazi Germany fought one war, which it lost as thoroughly and completely as it is possible to lose; in a sense the Nazis are necessarily tied for the position of “worst regime at war in history” by virtue of having never won a war, nor survived a war, nor avoided a war. Hitler’s decision, while fighting a great power with nearly as large a resource base as his own (Britain) to voluntarily declare war on not one (USSR) but two (USA) much larger and in the event stronger powers is an act of staggeringly bad strategic mismanagement. The Nazis also mismanaged their war economy, designed finicky, bespoke equipment ill-suited for the war they were waging and ran down their armies so hard that they effectively demodernized them inside of Russia. It is absolutely the case that the liberal democracies were unprepared for 1940, but it is also the case that Hitler inflicted upon his own people – not including his many, horrible domestic crimes – far more damage than he meted out even to conquered France.

Beyond these two, the next most “clearly fascist” government is generally Francisco Franco’s Spain – a clearly right-authoritarian regime, but there is some argument as to if we should understand them as fascist. Francoist Spain may have one of the best war records of any fascist state, on account of generally avoiding foreign wars: the Falangists win the Spanish Civil War, win a military victory in a small war against Morocco in 1957-8 (started by Moroccan insurgents) which nevertheless sees Spanish territory shrink (so a military victory but a strategic defeat), rather than expand, and then steadily relinquish most of their remaining imperial holdings. It turns out that the best “good at war” fascist state is the one that avoids starting wars and so limits the wars it can possibly lose.

Broader definitions of fascism than this will scoop up other right-authoritarian governments (and start no end of arguments) but the candidates for fascist or near-fascist regimes that have been militarily successful are few. Salazar (Portugal) avoided aggressive wars but his government lost its wars to retain a hold on Portugal’s overseas empire. Imperial Japan’s ideology has its own features and so may not be classified as fascist, but hardly helps the war record if included. Perón (Argentina) is sometimes described as near-fascist, but also avoided foreign wars. I’ve seen the Baathist regimes (Assad’s Syria and Hussein’s Iraq) described as effectively fascist with cosmetic socialist trappings and the military record there is awful: Saddam Hussein’s Iraq started a war of choice with Iran where it barely managed to salvage a brutal draw, before getting blown out twice by the United States (the first time as a result of a war of choice, invading Kuwait!), with the second instance causing the end of the regime. Syria, of course, lost a war of choice against Israel in 1967, then was crushed by Israel again in another war of choice in 1973, then found itself unable to control even its own country during the Syrian Civil War (2011-present), with significant parts of Syria still outside of regime control as of early 2024.

And of course there are those who would argue that Putin’s Russia today is effectively fascist (“Rashist”) and one can hardly be impressed by the Russian army managing – barely, at times – to hold its own in another war of choice against a country a fourth its size in population, with a tenth of the economy which was itself not well prepared for a war that Russia had spent a decade rearming and planning for. Russia may yet salvage some sort of ugly draw out of this war – more a result of western, especially American, political dysfunction than Russian military effectiveness – but the original strategic objectives of effectively conquering Ukraine seem profoundly out of reach while the damage to Russia’s military and broader strategic interests is considerable.

I imagine I am missing other near-fascist regimes, but as far as I can tell, the closest a fascist regime gets to being effective at achieving desired strategic outcomes in non-civil wars is the time Italy defeated Ethiopia but at such great cost that in the short-term they could no longer stop Hitler’s Anschluss of Austria and in the long-term effectively became a vassal state of Hitler’s Germany. Instead, the more standard pattern is that fascist or near-fascist regimes regularly start wars of choice which they then lose catastrophically. That is about as bad at war as one can be.

We miss this fact precisely because fascism prioritizes so heavily all of the signifiers of military strength, the pageantry rather than the reality and that pageantry beguiles people. Because being good at war is so central to fascist ideology, fascist governments lie about, set up grand parades of their armies, create propaganda videos about how amazing their armies are. Meanwhile other kinds of governments – liberal democracies, but also traditional monarchies and oligarchies – are often less concerned with the appearance of military strength than the reality of it, and so are more willing to engage in potentially embarrassing self-study and soul-searching. Meanwhile, unencumbered by fascism’s nationalist or racist ideological blinders, they are also often better at making grounded strategic assessments of their power and ability to achieve objectives, while the fascists are so focused on projecting a sense of strength (to make up for their crippling insecurities).

The resulting poor military performance should not be a surprise. Fascist governments, as Eco notes, “are condemned to lose wars because they are constitutionally incapable of objectively evaluating the force of the enemy”. Fascism’s cult of machismo also tends to be a poor fit for modern, industrialized and mechanized war, while fascism’s disdain for the intellectual is a poor fit for sound strategic thinking. Put bluntly, fascism is a loser’s ideology, a smothering emotional safety blanket for deeply insecure and broken people (mostly men), which only makes their problems worse until it destroys them and everyone around them.

This is, however, not an invitation to complacency for liberal democracies which – contrary to fascism – have tended to be quite good at war (though that hardly means they always win). One thing the Second World War clearly demonstrated was that as militarily incompetent as they tend to be, fascist governments can defeat liberal democracies if the liberal democracies are unprepared and politically divided. The War in Ukraine may yet demonstrate the same thing, for Ukraine was unprepared in 2022 and Ukraine’s friends are sadly politically divided now. Instead, it should be a reminder that fascist and near-fascist regimes have a habit of launching stupid wars and so any free country with such a neighbor must be on doubly on guard.

But it should also be a reminder that, although fascists and near-fascists promise to restore manly, masculine military might, they have never, ever actually succeeded in doing that, instead racking up an embarrassing record of military disappointments (and terrible, horrible crimes, lest we forget). Fascism – and indeed, authoritarianisms of all kinds – are ideologies which fail to deliver the things a wise, sane people love – liberty, prosperity, stability and peace – but they also fail to deliver the things they promise.

These are loser ideologies. For losers. Like a drunk fumbling with a loaded pistol, they would be humiliatingly comical if they weren’t also dangerous. And they’re bad at war.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, February 23, 2024 (On the Military Failures of Fascism)”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-02-23.

August 3, 2024

The Battle of Lepanto, 7 October 1571

Big Serge looks at the decisive battle between the “Holy League” (Spain, Venice, Genoa, Savoy, Tuscany, the Papal States and the Order of St. John) against the Ottoman navy in the Ionian Sea in 1571:

“The Battle of Lepanto”

Oil painting by Juan Luna, 1887. From the Senate of Spain collection via Wikimedia Commons.

Lepanto is a very famous battle, and one which means different things to different people. To a devout Roman Catholic like Chesterton, Lepanto takes on the romanticized and chivalrous form of a crusade — a war by the Holy League against the marauding Turk. At the time it was fought, to be sure, this was the way many in the Christian faction thought of their fight. Chesterton, for his part, writes that “the Pope has cast his arms abroad for agony and loss, and called the kings of Christendom for swords about the Cross”.

For historians, Lepanto is something like a requiem for the Mediterranean. Placed firmly in the early-modern period, fought between the Catholic powers of the inland sea and the Ottomans, then on the crest of their imperial rise, Lepanto marked a climactic ending to the long period of human history where the Mediterranean was the pivot of the western world. The coasts of Italy, Greece, the Levant, and Egypt — which for millennia had been the aquatic stomping grounds of empire — were treated to one more great battle before the Mediterranean world was permanently eclipsed by the rise of the Atlantic powers like the French and English. For those particular devotees of military history, Lepanto is very famous indeed as the last major European battle in which galleys — warships powered primarily by rowers — played the pivotal role.

There is some truth in all of this. The warring navies at Lepanto fought a sort of battle that the Mediterranean had seen many times before — battle lines of rowed warships clashing at close quarters in close proximity to the coast. A Roman, Greek, or Persian admiral may not have understood the swivel guns, arquebusiers, or religious symbols of the fleets, but from a distance they would have found the long lines of vessels frothing the waters with their oars to be intimately familiar. This was the last time that such a grand scene would unfold on the blue waters of the inner sea; afterwards the waters would more and more belong to sailing ships with broadside cannon.

Lepanto was all of these things: a symbolic religious clash, a final reprise of archaic galley combat, and the denouement of the ancient Mediterranean world. Rarely, however, is it fully understood or appreciated in its most innate terms, which is to say as a military engagement which was well planned and well fought by both sides. When Lepanto is discussed for its military qualities, stripped of its religious and historiographic significance, it is often dismissed as a bloody, unimaginative, and primitive affair — a mindless slugfest (the stereotypical “land battle at sea”) using an archaic sort of ship which had been relegated to obsolescence by the rise of sail and cannon.

Here we wish to give Lepanto, and the men who fought it, their proper due. The continued use of galleys well into the 16th century did not reflect some sort of primitiveness among the Mediterranean powers, but was instead an intelligent and sensible response to the particular conditions of war on that sea. While galleys would, of course, be abandoned eventually in favor of sailing ships, at Lepanto they remained potent weapons systems which fit the needs of the combatants. Far from being a mindless orgy of violence, Lepanto was a battle characterized by intelligent battle plans in which both the Turkish and Christian command sought to maximize their own advantages, and it was a close run and well fought affair. Lepanto was indeed a swan song for a very old form of Mediterranean naval combat, but it was a well conceived and well fought one, and Turkish and Christian fleets alike did justice to this venerable and ancient form of battle.

June 22, 2024

The End of Everything

In First Things, Francis X. Maier reviews Victor Davis Hanson’s recent work The End of Everything: How Wars Descend into Annihilation:

A senior fellow in military history and classics at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, Hanson is a specialist on the human dimension and costs of war. His focus in The End of Everything is, as usual, on the past; specifically, the destruction of four great civilizations: ancient Thebes, Carthage, Constantinople, and the Aztec Empire. In each case, an otherwise enduring civilization was not merely conquered, but “annihilated” — in other words, completely erased and replaced. How such catastrophes could happen is the substance of Hanson’s book. And the lessons therein are worth noting.

In every case, the defeated suffered from fatal delusions. Each civilization overestimated its own strength or skill; each misread the willingness of allies to support it; and each underestimated the determination, strength, and ferocity of its enemy.

Thebes had a superb military heritage, but the Thebans’ tactics were outdated and their leadership no match for Macedon’s Alexander the Great. The city was razed and its surviving population scattered. Carthage — a thriving commercial center of 500,000 even after two military defeats by Rome — misread the greed, jealousy, and hatred of Rome, and Roman willingness to violate its own favorable treaty terms to extinguish its former enemy. The long Roman siege of the Third Punic War saw the killing or starvation of 450,000 Carthaginians, the survivors sold into slavery, the city leveled, and the land rendered uninhabitable for a century.

The Byzantine Empire, Rome’s successor in the East, survived for a millennium on superior military technology, genius diplomacy, impregnable fortifications, and confidence in the protection of heaven. By 1453, a shrunken and sclerotic Byzantine state could rely on none of these advantages, nor on any real help from the Christian West. But it nonetheless clung to a belief in the mantle of heaven and its own ability to withstand a determined Ottoman siege. The result was not merely defeat, but the erasure of any significant Greek and Christian presence in Constantinople. As for the Aztecs, they fatally misread Spanish intentions, ruthlessness, and duplicity, as well as the hatred of their conquered “allies” who switched sides and fought alongside the conquistadors.

The industrial-scale nature of human sacrifice and sacred cannibalism practiced by the Aztecs — more than 20,000 captives were ritually butchered each year — horrified the Spanish. It reinforced their fury and worked to justify their own ferocious violence, just as the Carthaginian practice of infant sacrifice had enraged the Romans. In the end, despite the seemingly massive strength of Aztec armies, a small group of Spanish adventurers utterly destroyed Tenochtitlán, the beautiful and architecturally elaborate Aztec capital, and wiped out an entire culture.

History never repeats itself, but patterns of human thought and behavior repeat themselves all the time. We humans are capable of astonishing acts of virtue, unselfish service, and heroism. We’re also capable of obscene, unimaginable violence. Anyone doubting the latter need only check the record of the last century. Or last year’s October 7 savagery, courtesy of Hamas.

The takeaway from Hanson’s book might be summarized in passages like this one:

Modern civilization faces a toxic paradox. The more that technologically advanced mankind develops the ability to wipe out wartime enemies, the more it develops a postmodern conceit that total war is an obsolete exercise, [assuming, mistakenly] that disagreements among civilized people will always be arbitrated by the cooler, more sophisticated, and more diplomatically minded. The same hubris that posits that complex tools of mass destruction can be created but never used, also fuels the fatal vanity that war itself is an anachronism and no longer an existential concern—at least in comparison to the supposedly greater threats of naturally occurring pandemics, meteoric impacts, man-made climate change, or overpopulation.

Or this one:

The gullibility, and indeed ignorance, of contemporary governments and leaders about the intent, hatred, ruthlessness, and capability of their enemies are not surprising. The retreat to comfortable nonchalance and credulousness, often the cargo of affluence and leisure, is predictable given unchanging human nature, despite the pretensions of a postmodern technologically advanced global village.

I suppose the lesson is this: There’s nothing sacred about the Pax Americana. Nothing guarantees its survival, legitimacy, comforts, power, or wealth. A sardonic observer like the Roman poet Juvenal — were he alive — might even observe that today’s America seems less like the “city on a hill” of Scripture, and more like a Carthaginian tophet, or the ritual site of child sacrifice. Of course, that would be unfair. A biblical leaven remains in the American experiment, and many good people still believe in its best ideals.

June 21, 2024

June 18, 2024

Spice: King Of The Poor Man’s Kitchen

Townsends

Published Mar 3, 2024One of the questions we seek to answer on our channel is that of the plight of poor folks in American history. What did they eat? How did they dress? Did they have enjoyment in life? They didn’t have the best cuts of meat or the most sought after ingredients. What they did have was plenty of flavor! Spice is the king of the poor man’s kitchen.

(more…)

June 16, 2024

June 3, 2024

18th Century Spiced Hot Chocolate

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Feb 23, 2024Rich, thick, dark hot chocolate spiced with cinnamon and cardamom

City/Region: England

Time Period: 1747Up until the 19th century, the most popular way to partake of chocolate was to drink it. Aztecs drank a very bitter chocolate, and when Europeans brought it back home, they paved the way for one of the most perfect of food pairings: chocolate and sugar.

This hot chocolate is fairly dark, so feel free to add more sugar if that’s to your taste. It’s super rich and much thicker than most hot chocolates you’d get today, so you may only want to make a small amount of the drink and save the rest of the chocolate for later. The spices jump out at you, and even though mine still had a bit of grittiness from the cocoa nibs (it’s basically impossible to get it completely smooth at home), it was really, really good.

(more…)

May 8, 2024

QotD: Imperial Spain’s “House of Trade”

Since 1503, the Spanish port of Seville had been home to the Casa de Contratación, or House of Trade. In one sense, the Casa was an administrative centre. It was where all taxes and duties on trade with the New World were collected. In another sense, however, it was the sixteenth century’s most important research and development hub. It was where the maps were made. Anyone who crossed the Atlantic was to check in with the Casa and share their information. There, the expert pilots, astronomers, mathematicians, and cartographers, were to sort out the sailors’ tall tales from the careful observations of coastlines. The Casa institutionalised the practice of gathering information – everything from the locations of safe havens or treacherous rocks, to the willingness of local populations to talk to strangers, to the raw materials glimpsed in newfound lands – all to be collated, evaluated, and then re-disseminated into manuals, lectures, and maps. It was where new pilots were instructed, and where navigational instruments were constructed and regulated. The Casa was a living encyclopaedia of navigation, for every would-be Spanish merchant, coloniser, or explorer to consult.

And it was something that the English tried, for decades, to emulate. Before they embarked on their first explorations of the icy seas around Russia in the 1550s, they first poached the Casa‘s principal navigator, the Pilot Major, Sebastian Cabot. And later, during the few years that England and Spain were united in matrimony, under Mary I, one English navigator, Stephen Borough, had the chance to visit and glean some of its secrets. He was instrumental in having Spain’s key navigational manual translated in English, and he petitioned Elizabeth I to create an English version of the Casa. That dream never materialised, but the quest to emulate the Casa informed many of the smaller-scale projects — lectures, manuals, globes, and maps — which meant that the English did not sail completely into the unknown.

Anton Howes, “The House of Trade”, Age of Invention, 2019-11-13.

February 4, 2024

January 18, 2024

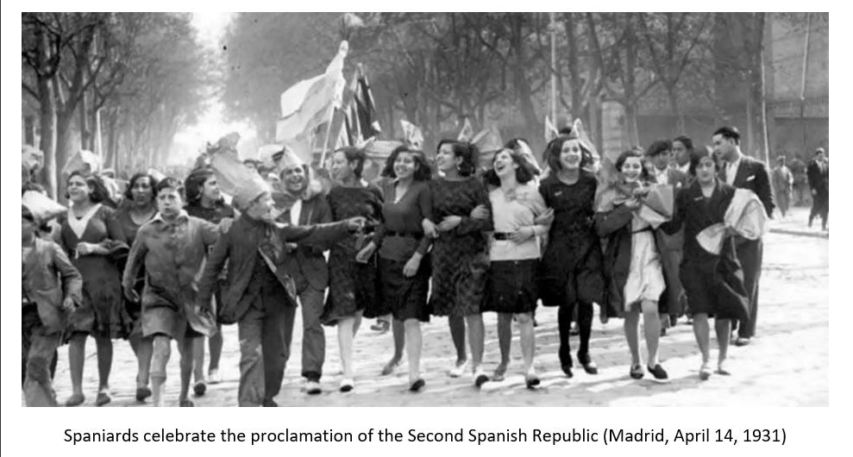

Understanding the Spanish Civil War

Niccolo Soldo offers an introduction to the context in which the Spanish Civil War took place, with emphasis on one side’s uneasy coalition of interests:

Picasso’s “Guernica” in mural form in the town of Guernica.

Photo by Papamanila via Wikimedia Commons.

At a crossroads in his life, [Ernest Hemingway] decided to go to Spain to cover the conflict for a newspaper chain. Out of his experiences in that war came For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), one of his most celebrated novels. In this excerpt, he uses the female character “Pilar” to relate the story of how Republican forces massacred a group of people in a small town who were opposed to the government and supported the Spanish Generals seeking to overthrow it. Derided as “fascists”, each of the men were forced to pass a line of pro-government peasants who would beat them with flails before throwing them off of a cliff. Civil wars are indeed the most vicious, even in fictional depictions like this one.

The Spanish Civil War is odd for two reasons, the first one being that more than any other war that I can think of, historians have placed a much stronger focus on the politics of the conflict to the detriment of its military aspects. The second reason is much more important overall, and particularly germane to the subject of this essay: it is the only war that I can think of where the histories have been overwhelmingly written by the losers.1

If you ask a random, somewhat educated person in the West about the Spanish Civil War, they will generally say that “Franco was a fascist who allied himself to Hitler and Mussolini and won the civil war in the most brutal fashion possible. He was a dictator who hated democracy and killed thousands upon thousands of innocent people.” Beyond that, they might make mention of Hemingway and his novel, or even Pablo Picasso’s painting entitled “Guernica”2, that depicts the victims of the German Luftwaffe bombardment of that small Basque town in the north of Spain. Others still will relay the fact that the term “Fifth Column” came out of the Spanish Civil War.3 Added up all together, the most simplified take becomes “Franco bad, Republicans good”.

Of course this take is wrong, as this conflict was too complex to arrive at such a ridiculous reductionist conclusion no matter which side you sympathize(d) with. To give you a quick illustration of just how complex this conflict was, here is a list of the major domestic factions that took part in it:

Spanish Republican Side:

- People’s Army (the armed forces of the Spanish Republic)

- Popular Front (left-wing electoral alliance of communists, socialists, liberals, anarchists)

- UGT (very large trade union affiliated with the Spanish Socialists)

- CNT-FAI (massive trade union of anarchist militants)

- POUM (anti-Stalinist communists, including some Trotskyites)4

- Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalonian Autonomists)

- Euzko Gudarostea (Army of the Basque Nationalists)

Spanish Nationalist Side:

- Spanish Renovation (monarchists supporting the Bourbon claimant to the throne, Alfonso XIII, who abdicated in 1931)

- CEDA (the main conservative party, Catholic conservatives)

- Requetés (traditionalist Catholic monarchist militants who supported the Carlist Dynasty, mainly from the region of Navarre)

- Falange Española de las JONS (Spanish Fascists)

- The Army of Africa, including the Spanish Legion (Spanish Army in Spain’s then-colony of Morocco, with many Moroccans serving in it)

Add to this mix the International Brigades5 that fought on the side of the government, and the German and Italian forces who backed the rebels. To list off all the political groupings that participated in the war is a mouthful, but necessary to hammer home the point of the complexity of this conflict. So here goes: nationalists, monarchists (from two competing royal houses), fascists, conservatives, liberals, social democrats, socialists, communists (from two competing camps), anarchists, and regional autonomists. In short, this war had something for everyone, which is why it caught the attention of so many foreigners (especially famous ones) at the time. But before we dive into the run up to the civil war, we need to understand some of the history of Spain that lead up to this “world war in miniature”.

1. “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it” – falsely attributed to Winston Churchill, but it makes for a good quote to illustrate the point. From the International Churchill Society: “‘Alas poor Baldwin. History will be unkind to him. For I will write that history.’ And another version often repeated is ‘History will be kind to me. For I intend to write it.’

What Churchill actually said, in the House of Commons in January 1948, was in response to a speech by Herbert Morrison, the Labour Lord Privy Seal, which attacked the Conservatives’ foreign policy before the war:

“For my part, I consider that it will be found much better by all parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history myself.”

2. In January of 1937, Picasso was commissioned by the Spanish Republican government to create a work of art to display at the upcoming World’s Fair in Paris in order to draw international attention to their cause. At the time, Picasso was living in the French capital. It wasn’t until he read reports of the bombing of Guernica on April 26 of that same year that he felt inspired enough to create something that he felt was worthwhile for audiences to see.

3. In September 1936, General Francisco Franco supposedly claimed that there were “four nationalist columns approaching Madrid, and a fifth column inside of it ready to attack”.

4. Leon Trotsky did not support POUM and went on to disassociate himself from them and their actions. George Orwell joined POUM when he went to Spain to volunteer to fight against the Spanish nationalists.

5. Formed by volunteers from outside of Spain and almost entirely Stalinist in leadership and political orientation.

October 17, 2023

Sherry Wine of Andalucía

The Culinary Institute of America

Published 13 Nov 2012Andalucía is well known for its sherry, a fortified wine made near the town of Jerez. Sherry is a protected designation of origin; and in Spanish law, all wine labeled as “Sherry” must come from the Sherry Triangle, an area between Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, and El Puerto de Santa María.

For recipes, please visit http://www.ciaprochef.com/andalucia.