The final objective we can be quite certain about is that Sparta aimed to protect the internal social and political order of Sparta, which essentially amounts to a strategic objective to be able to continue mistreating the helots and the perioikoi. In practice – given Sparta’s desperate shortness of manpower (and economic resources!) and continued unwillingness to revisit the nature of its oppressive class system, we may say with some confidence that Sparta effectively sacrificed all other objectives on the altar of this one.

And yet Sparta’s failure here was perhaps the most complete of all. The collapse of the Spartiate class did not abate after Leuktra; by the 230s, there were hardly any Spartiates left. Meanwhile, the transition of Messenia from a group of subject communities supporting Sparta economically to an active and hostile power on Sparta’s border essentially represented the end of the Spartan social order as established in the seventh century with the reduction of Messenia to helotry in the first place.

So, does Sparta achieve its strategic objectives? By and large, I think the answer here has to be “no”. Sparta – the supposed enemy of tyrants – by mismanaging its own leadership invited one foreign oppressor (Macedon) into Greece after another (Persia). As a state that seems – to me at least – to have considered itself the natural and rightful leader of all of the Greek states, Sparta, routinely and comprehensively proved itself unworthy of the position.

The one thing we may say for Spartan foreign and military policy is that it seems to have made the world safe for helotry – it preserved the brutal system of oppression which was foundational to the Spartan state. But consider just how weak an achievement that is – we might, after all, make the same claim about North Korea: it has managed only to successfully preserve its own internal systems of oppression.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Part VII: Spartan Ends”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-09-27.

January 19, 2023

QotD: Did Sparta achieve its strategic objectives?

January 18, 2023

Our western gerontocracy

In The Free Press, Katherine Boyle outlines the death-grip that elderly boomers retain on so many of the levers of our shared society, from government to business to (of course) the legacy media:

“Millennials” by EpicTop10.com is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The tens of millions of Americans that are, like me, millennials or members of the generation just younger, Gen Z, have been treated as hapless children our entire lives. We have been coded as “young” in business, in politics, and in culture. All of which is why we shouldn’t be surprised that millennials are the most childless and least home-owning generation in modern American history. One can’t play house with a spouse or have their own children when they’ve moved back into mom’s, as 17 percent of millennials have.

Aside from the technology sector — which prizes outliers, disagreeableness, creativity and encourages people in their twenties to take on the founder title and to build things that they own — most other sectors of American life are geriatric.

The question is why.

There are many theories — and many would-be culprits. Some believe it’s the fault of the Boomers, who have relentlessly coddled their children, perhaps subconsciously, because they don’t want to pass the baton. Others put the blame on the young, who are either too lazy, too demoralized or too neurotic to have beaten down the doors of power to demand their turn.

Then again, life expectancy is growing among the healthy and elite in industrialized nations, so perhaps this is all just progress and 70 is the new 40. But one can take little solace in the growing life expectancy of the last 200 years when comparing ourselves to more productive generations that didn’t waste decades on extended adolescence.

Every Independence Day, we’re reminded that on July 4, 1776, the most famous founders of this country were in their early 20s (Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr) and early 30s (Thomas Jefferson). Even grandfatherly George Washington was a mere 44. These days much of our political class, from Bill Clinton (elected president 30 years ago at age 46) to financial leaders like Warren Buffett (92), and Bill Gates (67) who launched Microsoft 48 years ago, are still dominant three and four decades after seizing the reins of power. CEOs of companies listed on the S&P 500 are getting older and staying in their jobs longer, with the average CEO now 58 years old and staying in his or her role 10.8 years versus 7.2 a decade ago. And our political culture looks even more gray: Twenty-five percent of Congress is now over the age of 70 giving us the oldest Congress of any in American history.

The Boomer ascendancy in America and industrialized nations has left us with a global gerontocracy and a languishing generation waiting in the wings. Not only does extended adolescence — what psychologist Erik Erikson first referred to as a “psychosocial moratorium” or the interim years between childhood and adulthood — affect the public life of younger generations, but their private lives as well.

In 1990, the average age of first marriage in the U.S. was 23 for women and 26 for men, up from 20 for women and 22 for men in 1960. By 2021, that number had risen to 28.6 years for women and 30.4 years for men, according to the Census Bureau, with 44 percent of U.S. women between the ages of 25 and 44 expected to be single in 2030. Delayed adulthood has had disastrous consequences for procreation in industrialized nations and is at the root of declining fertility and all-but-certain population collapse in dozens of countries, many of which expect the halving of their populations by the end of the century.

“Twenty-five is the new 18,” said The Scientific American in 2017, pointing to research that extended adolescence is a byproduct of affluence and progress in society. Which is why the finiteness of a mid-thirties half-life is such a surprise to those in their 20s and 30s. It runs counter to every meme and piece of advice young people receive about building a career, a family, a company and in turn, a country.

The prevailing wisdom in Western nations is that the ages of 18-29 are a time for extreme exploration — the collecting of memories, friends, partners and most importantly, self-identity. A full twelve years of you! Self-discovery aided by platforms built for broadcasting photos of artisanal cocktails and brunch. And with no expectation for leadership because there will be time for that, a generation can absolve oneself of responsibility for their actions. (Tragically, that was never true for half of the population, which is why we have a generation of extremely accomplished older women, who weren’t really aware how difficult it is to become pregnant at 39.)

The Roman Army, With Adrian Goldsworthy

Well That Aged Well

Published 12 May 2021In this episode we take a look at the Roman Army, and its comanders. What made the Roman Army so efficent? Was it the practice? The motivation? Their courrage? Or was it more to it? Find out in this week’s episode of “Well That Aged Well”, With Erlend Hedegart.

(more…)

L’affaire Dreyfus

Robert Zaretsky on an espionage scandal that convulsed the French Third Republic and still has resonance down to today:

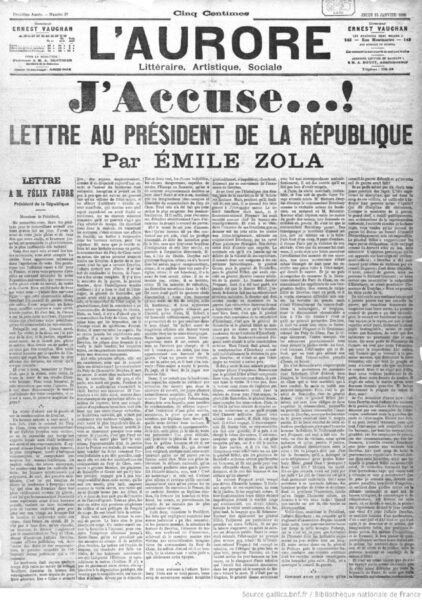

On January 13, 1898, Parisians awoke to the chorus of hundreds of news criers who, striding along the grand boulevards and brandishing copies of the newspaper L’Aurore, were shouting passages from the article that sprawled across the front page. It had originally been titled by its author, the novelist Émile Zola, “A Letter to M. Félix Faure, President of the Republique”. But with a flair for the sensational, the newspaper’s editor, Georges Clemenceau, slapped on a punchier headline. Stepping out of a department store or stepping down from a carriage, sitting at a café or standing at an intersection, pedestrians were greeted by two words that continue to resonate 125 years to the day after their first publication: “J’Accuse!”

With this exclamation, Zola’s letter transformed une affaire judiciare into l’affaire Dreyfus or, more simply, the Dreyfus Affair. It catapulted the French novelist onto the world stage at a critical moment in the history of his country, which was reeling from the forces of globalisation and industrialisation and riven by opposing understandings of its revolutionary heritage. It is thus hardly surprising that Zola’s fame rests more heavily on the letter than on his sweeping 20-volume masterpiece of literary realism, the Rougon-Macquart. It took a novelist to heave the facts of this affair into a narrative which, more than a century later, thrums with equal urgency. Moreover, as with the novels of the Rougon-Macquart, the letter thrusts onto centre-stage a lone individual swept up, and all too often swept under, the political and social, irrational and ideological forces of the modern age.

It all began with the contents of a rubbish bin. In September 1894, a cleaning woman at the German Embassy, in the pay of France’s military intelligence service, delivered her nightly harvest to her employers. Buried in the mound of discarded papers was a memorandum, known as the bordereau or note, revealing top secret advances in French artillery technology and tactics. In a frantic scramble to find its author, the war ministry’s suspicion settled on Captain Alfred Dreyfus, an officer in the High Command who stood out for his standoffishness and Jewishness.

Upon being arrested and charged, a bewildered Dreyfus denied the charges, pointing out several things mentioned in the bordereau he could not possibly have known. The seven members of the military tribunal, ignoring these inconsistencies as well as the insistence of their own graphologist that Dreyfus’s handwriting did not match the bordereau‘s, unanimously found him guilty. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in solitary confinement on Devil’s Island, a malarial rock off the coast of French Guyana.

But first came a remarkable ritual of public humiliation. Dreyfus was marched into the courtyard of the École militaire, the renowned military academy a short distance from the recently erected Eiffel Tower. In the shadow of that monument to modernity, an officer preceded to snap Dreyfus’s sword — broken and soldered back together with tin the night before, to make the gesture seem effortless — and tear off his insignia — whose threads were already loosened — while a dense crowd howled with calls for the death of the “Jewish traitor!”

Two years later, as Dreyfus wasted away in solitary confinement, Colonel Georges Picquart, the newly appointed head of military intelligence, found that another missive about French military plans had ended up in the rubbish bin at the German Embassy. Moreover, the handwriting on this new document, which matched that of the bordereau, also matched the hand of Ferdinand Esterhazy, an officer notorious for his womanising and gambling.

Picquart disliked Jews as much as his many of his fellow officers did. But when his commanding officer asked him why it mattered if “this Jew remains on Devil’s Island”, Picquart replied: “Because he is innocent!” The answer earned Picquart a rapid transfer to a desert outpost in North Africa. Before he was packed off, though, Picquart vowed that he would not “carry this secret to my grave”. He then shared what he knew with Auguste Scheurer-Kestner, the leader of Dreyfusards, a small but growing coterie of politicians and writers seeking a retrial for Dreyfus.

In late 1897, Zola met with Scheurer-Kestner, who told him about Picquart’s discovery. As the mesmerised novelist listened, he glimpsed the theatrical as well as moral dimensions of the affair. “It’s thrilling!” he gasped. “It’s frightful! But it is also drama on the grand scale!” It took Zola to scale it to greatness by flipping Oscar Wilde’s sly quip that anyone could make history, but only a great man could write it. Instead, Zola showed, a man becomes truly great only by, in every sense of the word, making history.

Ask Ian: Why No German WW2 50-Cal Machine Guns? (feat. Nick Moran)

Forgotten Weapons

Published 20 Sep 2022From Nathaniel on Patreon:

“Why didn’t Germany or Axis powers have a machine gun similar to the American M2?”Basically, because everyone faced the choice of a .50 caliber machine gun or 20mm (or larger) cannons for anti-aircraft use, and most people chose the cannons — including Germany. There were some .50 caliber machine guns adopted by Axis powers, most notably the Hotchkiss 1930, a magazine-fed 13.2mm gun that was used by both Italy and Japan (among others). However, the use of the .50 caliber M2 by the US was really a logistical holdover form the interwar period. The M2 remained in production because it was adopted by US Coastal Artillery as a water-cooled anti-aircraft gun, and commercial sales by Colt were slim but sufficient to keep the gun in development through the 20s and 30s. It was used as a main armament in early American armor, but obsolete in this role when the war broke out.

However, with the gun in production and no obvious domestic 20mm design, the US chose to simply make an astounding number of M2s and just dump them everywhere, from Jeeps to trucks to halftracks to tanks to self-propelled guns. And that’s not considering the 75% of production that went to coaxial and aircraft versions …

Anyway, back to the question. The German choice for antiaircraft use was the 20mm and 37mm Flak systems, and not a .50 MG on every tank turret. And so, there was really no motive to develop such a gun. The Soviets did choose to go the US route, though, and developed the DShK-38 for the same role as the US M2 — although it was made in only a tiny fraction of the quantity of the M2.

(more…)

QotD: Tanks for Ukraine?

Lately we’ve been tap dancing up to even heavier gear [for Ukraine]. The US has announced we’ll be sending some M2 Bradley IFVs, and France chipped in some AMX-10 RC heavy armored cars. While referred to as a char, or tank, in French service and apparently some obscure EU regulation classifies anything above a certain weight and with a big enough gun as a tank … and the AMX-10 clears those hurdles … war nerds will insist that unless it comes from the tank region of France it’s just a sparkling armored fighting vehicle.

It looks like the inhibition on sending tanks is finally cracking, though. While Germany is still dithering over letting Poland send some of its Leopard 2’s, Britain has announced it’s sending 14 Challenger 2 main battle tanks.

I found that particular number interesting. Late Cold War and post-Cold War Russian armored units use three-tank platoons and three platoons plus a commander’s tank make a ten tank company.

The British Army, from whose stores the Challengers will be pulled, uses some archaic TO&E, possibly left over from the Wars of the Roses or Cromwell’s New Model Army, wherein four tanks equal a Bonnet*, and four Bonnets plus two more tanks in a headquarters Bonnet equal an eighteen-tank Spanner†.

Fourteen tanks, however, is enough for three four-tank platoons plus two tanks for an HQ platoon, equalling a fourteen tank US-style armored company. Apparently the Ukies are using a US/(most of)NATO TO&E for their armored units. So the Ukrainians will have at least one company of Western MBTs.

* Bonnet = Troop

† Spanner = SquadronTamara Keel, “Clank Clank Goes the Tank”, View From The Porch, 2023-01-15.

January 17, 2023

“Karl Marx was one hollow and rotten tree, inside and out, from beginning to end”

To mark the passing of Paul Johnson, the Foundation for Economic Education reposted an appreciation of Johnson’s Intellectuals by Lawrence W. Reed praising his essay on Karl Marx:

None of Johnson’s subjects can match Karl Marx for sheer loathsomeness and shameless fakery. He was a virulent racist and anti-Semite with a vicious temper (“Jewish n****r” was one of his favorite epithets). On a good day, he enjoyed threatening those who disagreed with him by blurting, “I will annihilate you!” His personal hygiene was, well, suffice it to say he had none. He was heartlessly cruel to his family and anyone who crossed him. This is the same man who postured as a thinker whose ideas would save humanity.

We learn in Intellectuals that the chef who cooked up communism professed to be “scientific”. In reality, Johnson argues, “there was nothing scientific about him; indeed, in all that matters he was anti-scientific”. His most famous lines — including “religion is the opiate of the masses” and workers “have nothing to lose but their chains” — were flagrantly ripped off from other authors. He “never set foot in a mill, factory, mine or other industrial workplace in the whole of his life”, steadfastly abjured invitations to do so, and denounced fellow revolutionaries who did. He never let a fact or a glimmer of reality stem the flow of poison from his pen. He had no money because he refused to work for it, then cursed those who had it and didn’t share it with him. His own mother said she wished her son “would accumulate some capital instead of just writing about it”.

And that’s for starters. Read Johnson’s chapter on Marx, and you’ll begin to understand the connection between the evil within the man and the evil his gibberish wrought. The Black Book of Communism estimates the death toll from attempts to put the rantings of this detestable lunatic into practice at minimally 100 million.

“What emerges from a reading of Capital is Marx’s fundamental failure to understand capitalism”, writes Johnson.

He failed precisely because he was unscientific: he would not investigate the facts himself, or use objectively the facts investigated by others. From start to finish, not just Capital but all his work reflects a disregard for truth which at times amounts to contempt. That is the primary reason why Marxism, as a system, cannot produce the results claimed for it; and to call it “scientific” is preposterous.

Many people who don’t know better, and an awful lot of those in “intellectual” circles who should, still think Karl Marx was some sort of prescient genius motivated by compassion for workers. Some even disgrace themselves with T-shirts bearing his unkempt image. They really ought to thank Paul Johnson for doing the thinking they themselves never made time for.

Actually, we were warned about people like Marx 2,000 years before Johnson. Matthew 7:16 wisely counsels:

Beware of false prophets. They come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravenous wolves. By their fruit you will know them. Are grapes gathered from thornbushes, or figs from thistles? Likewise, every good tree bears good fruit, but a bad tree bears bad fruit.

Karl Marx was one hollow and rotten tree, inside and out, from beginning to end.

The Early Emperors, Part 11 – The Flavian Reconstruction

seangabb

Published 29 Dec 2022This is a video record of a lecture given by Sean Gabb, in which he discusses the three Flavian Emperors who ruled between 69 and 98 AD — Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian. He also discusses the Jewish Revolt and the eruption of Vesuvius.

The Roman Empire was the last and the greatest of the ancient empires. It is the origin from which springs the history of Western Europe and those nations that descend from Western Europe.

(more…)

How ideological programming in British schools make men like Andrew Tate inevitable

To be honest, I don’t think I’d ever heard of Andrew Tate before his legal troubles in Romania hit the headlines, and I’m not well-versed on his achievements (such as they might be). Janice Fiamengo also admits that Tate wasn’t on her radar before then, but she’s done some work to try to put him into perspective:

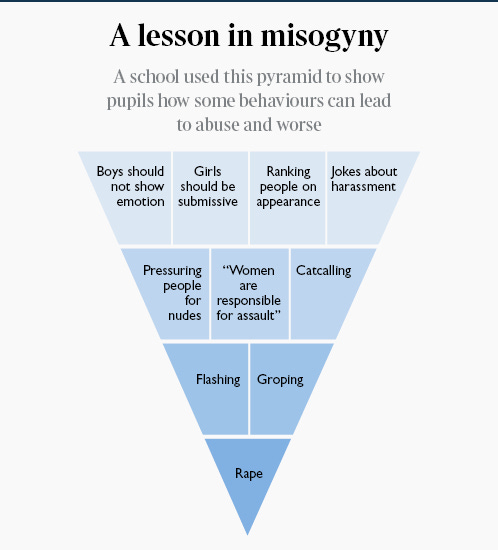

What has Tate got to do with UK education, except perhaps as a telling symbol of its unintended consequences? Why not just model and enforce ideals such as courtesy, self-restraint, and hard work, while upholding high academic standards? The article demonstrates how deeply committed schools have become to ideological programming. Some schools have drawn up “entire lessons focused on Tate” (!!!) while others deal more generally with “misogyny and gender stereotypes”. Whatever the particulars, the general message is unvarying: “We’ve all got to work collaboratively and collectively to support young men to reframe masculinity—away from this toxic ideology that’s presented by the likes of Tate.”

No one who’s been following the feminist narrative over the past decade or two will be surprised by the dogmatic reference to “toxic ideology,” now standard in any discussion of “reframing” boyhood. There is just one problem for the concerned teachers: Tate is five steps ahead of them, having already made clear to his millions of followers why injunctions about “reframing masculinity” are just code for the continual marginalization that most boys naturally want nothing to do with. The moment Tate and his allies expressed their scorn for the project, it lost its power overs the millions of boys forced to sit in feminist classrooms across the UK. Tate confirmed what boys intuitively knew: having their masculinity “reframed” will prevent them from pursuing masculine dreams, from being proud of themselves as male, admired by their male peers, and able to attract the interest of pretty girls. Teachers can keep on telling boys that peer approval through masculine moxy isn’t important, but that won’t make it true.

The point is not whether Tate’s (“I’ve got 33 cars“) program is an unalloyedly good one; the point is that it is manifestly better than the recipe for self-loathing and irrelevance being offered by the schools. The school’s program is the same that has been tried for years without any enthusiastic uptake because it offers nothing affirmatively male for young men to be and do (see especially White Ribbon UK, which has been trying for years to turn boys into handmaidens of feminism). All the normal things that centuries of boys in every major civilization on earth have cared about—competitiveness, status, toughness, mastery, knowledge, self-reliance, stoicism, high-jinks, displays of ability, and male bonding—are now frowned upon and must be replaced by feminine traits like empathy, egalitarianism, conformity, verbal display, and tone-policing. It doesn’t take a gender studies specialist to see that the life being offered these boys is one of deference, self-suppression, and self-contempt. No boy should want that.

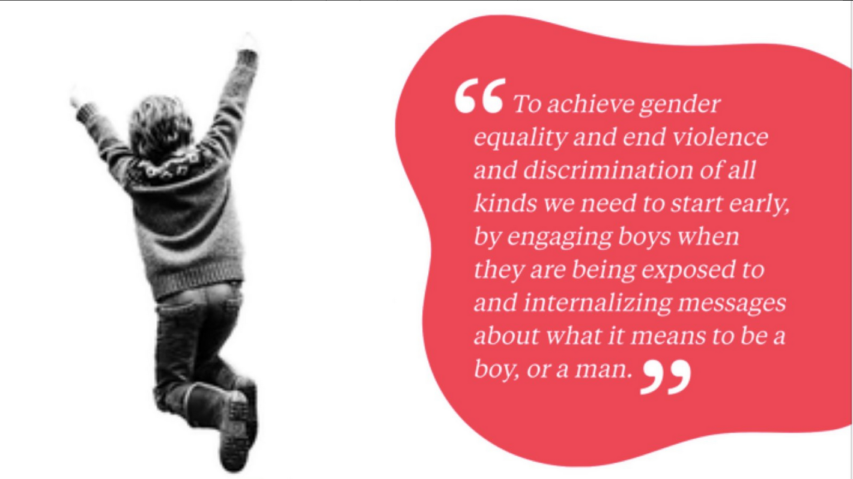

In case you doubt my characterization, take a look at the Global Boyhood Initiative’s report on The State of UK Boys: Understanding and Transforming Gender in the Lives of UK Boys, published in 2022. The report was written for “teachers, youth workers, early-years practitioners and other professionals” to achieve “gender equity and social justice”.

Incidentally, the report includes a section attacking an alleged “overemphasis” on research showing boys and men as victims of intimate partner violence by women. While the report enthusiastically promotes the end of “gender” through transgenderism and social constructivism, it emphatically does not support the end of gendered norms about which sex is violent. On this front, the report laments that “even young boys” now believe that male persons can be victimized by female persons, citing the case of Johnny Depp’s abuse by Amber Heard. Nothing could more clearly signal the report authors’ chagrined awareness of the difficulty of controlling boys’ thoughts in the internet age.

The rest of the report explores pathways to weaken masculinity. On a number of occasions, it takes aim at “simplistic notions that boys require male ‘role models'” because such notions “frame women as inadequate to parent and teach boys”. Taking for granted that “gender is not tied to sex organs, hormones, or biological traits” (one wonders, then, why trans persons elect to take hormones and to change their sex organs), the emphasis throughout the report is on “realigning” masculinity to highlight gender fluidity, transgenderism, and inclusion of girls. The document has absolutely nothing good to say about masculinity, which it describes, variously, as “a seductive form of power”, “hegemonic”, and “oppressive”. It even uses the derogatory term “boysplaining” to stigmatize boys’ alleged way of talking.

Even such seemingly benign behaviors as “laughter, banter, and entertaining one another” are said to be “laddish” and linked to the exclusion of women and homosexuals. Taking pleasure in being good at sport is also given a negative valence by being associated with bullying.

As in all such feminist propaganda, the report seeks the evacuation of all positive content from masculinity. “Realigned” boys are to anchor their sense of self mainly in not being what boys have always been. They are to shun the allegedly “hegemonic” characteristics of “physical, sexual, and mental prowess; being action-oriented; ‘knowing’; having autonomy […]; and being emotionally tough.” It is surely no coincidence that modern boys and young men have fallen well behind their female peers in educational attainment, economic status, and performance on the job market. “Prowess” is out, knowing is out, being active is out, toughness is out. No wonder so many boys feel lost, disaffected, and resentful, and no wonder some see Andrew Tate as a hero.

Growing an Ancient Roman Garden

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 23 Aug 2022

January 16, 2023

Paul Johnson on Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The book Paul Johnson may best be known for is Intellectuals, an essay collection highly critical of many of the “great men” of intellectual history. Birth of the Modern, the first Johnson book I read, was also skeptical of the bright lights of European intellectualism, but Intellectuals is where he concentrated on the biographical details of many of them. Ed West selected some of Johnson’s essay on Jean-Jacques Rousseau as part of his obituary post:

… Johnson is best known to many for his history books, one of the most entertaining being Intellectuals. Published in 1989 and structured as a series of – very critical – biographies of great philosophers, poets, playwrights and novelists, Johnson’s book got to the essence of the intellectual mindset in all its worst aspects: their intense selfishness and narcissism, their callousness towards friends and lovers, and their fondness for giving moral support to some of the worst ideas and regimes in history.

One of the most prominent Catholics in British journalism, Johnson saw secular intellectuals as modern successors to the theologians of the medieval Church, the difference being that, without the restraints of religious institutions, their egotism was uncontrolled.

Writers and artists are often incredibly selfish people, and this is true across the political spectrum, but of course it’s far more satisfying to read about those men who claimed to be the saviour of the poor and humble yet were so relentlessly horrible to actual people around them. That’s what makes the book – published just as the system imagined by one of its subjects came crashing down in eastern Europe – so satisfying.

One of the targets, er, I mean “subjects” of Intellectuals was Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was quite the piece of work indeed:

It begins with Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the “first of the modern intellectuals” and perhaps the subject of Johnson’s most intense vitriol.

“Older men like Voltaire had started the work of demolishing the altars and enthroning reason,” he wrote: “But Rousseau was the first to combine all the salient characteristics of the modern Promethean: the assertion of his right to reject the existing order in its entirety; confidence in his capacity to refashion it from the bottom in accordance with principles of his own devising belief that this could be achieved by the political process; and, not least, recognition of the huge part instinct, intuition and impulse play in human conduct.

“He believed he had a unique love for humanity and had been endowed with unprecedented gifts and insights to increase its felicity.” He was also an appalling human being.

[…]

Madame Louise d’Épinay, a lover who he treated terribly, said “I still feel moved by the simple and original way in which he recounted his misfortunes”. Another mistress, Madame de Warens, effectively supported him in hard times but, when she fell into destitution, he did nothing to prevent her dying of malnutrition.

Rousseau had a “pseudo-wedding” with his mistress Therese Levasseur where he gave a speech about himself, saying there would be statues erected to him one day and “it will then be no empty honour to have been a friend of Jean-Jacques Rousseau”. He later accused her brother of stealing his 42 fine shirts and when he had guests for dinner she was not allowed to sit down. He praised her as “a simple girl without flirtatiousness”, “timorous and easily dominated”.This easily-dominated woman gave birth to five of his children, whom he had sent to an orphanage where two-thirds of babies died within the first year and just one in 20 reached adulthood, usually becoming beggars. He made almost no attempt to ever track them down, and said having children was “an inconvenience”.

“How could I achieve the tranquillity of mind necessary for my work, my garret filled with domestic cares and the noise of children?” He would have been forced to do degrading work “to all those infamous acts which fill me with such justified horror”.

He was spared that horror and instead given time to develop his ideas, which were fashionable, attractive and completely unworkable. “The fruits of the earth belong to us all, the earth itself to none”, he said, and hoped that “the rich and the privileged would be replaced by the state which reflected the general will”.

What would this mean in practice? “The people making laws for itself cannot be unjust … The general will is always righteous”.

Despite his ideas veering between woeful naivety and sinister authoritarianism, they proved hugely popular, especially with the men and women who in 1789, just a decade after his death, would bring France’s old regime crashing down — with horrific consequences. As Thomas Carlyle famously said of Rousseau’s The Social Contract: “The second edition was bound in the skins of those who had laughed at the first.”

Rousseau was perhaps the most influential figure of the modern era. In particular his rejection of original sin would become far more popular in the late 20th century; indeed it is at the core of what we call the culture war, and its fundamental conflict over human nature.

The music industry fails to capitalize on the vinyl revival

It’s kind of hard to believe, but the companies that control the pressing of music into vinyl appear to have no clue about the business they’re in:

“Framed Vinyl Album Art: America ‘Homecoming’; Nick Gilder (Studio Copy of Singles From ‘City Lights’ Chosen for AOR); Climax Blues Band ‘FM Live’)” by JoeInSouthernCA is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

I’d heard so many grand claims for the vinyl resurgence, but the reality was tremendously disappointing. And I was a late adopter — the revival had been going on for a decade, but record labels still didn’t have their act together.

In my case, I ended up buying vinyl albums, but mostly used ones. I simply couldn’t find new pressings of the records I wanted. This was fine for me, but lousy for musicians and labels — who make no money on the sale of a secondhand vinyl album.

I have some experience in these matters — in my alternative career I worked with CEOs chasing after fast growth product categories. I know how they handle these situations. But, really, it’s no mystery. The strategies you use in this kind of business are very straightforward:

- You add manufacturing capacity aggressively — to make sure you have enough product to fuel growth.

- You bring down costs by getting scale advantages. But this only happens because unit costs drop as volume increases. So the single biggest goal is to grow sales as hard and fast as possible.

- You constantly reduce prices to keep demand building. In some cases, you even set prices below your costs to accelerate growth rates. When I originally saw companies do this I was skeptical — how can you make profits if you sell below your costs? But I soon learned that you eventually got a huge payback.

- You keep expanding the product line, so that you constantly have something new and exciting to sell to every potential buyer.

- You invest in R&D so that you eventually have a next generation technology to keep the growth going over the long haul.

None of this is easy to do, but it isn’t impossible. It just takes investment, focus, management commitment, and hard work. And later you reap the benefits. You turn a small business into a huge one, and enjoy a big payday.

The record labels could have done that with vinyl. It was taking off — unit sales doubled in just 5 years. And these sales were insanely profitable, because much of the demand was for old music. So labels didn’t even have to pay to sign artists, and cover the costs of recording sessions. The music was already there, with the fixed costs amortized long ago.

They just had to press the bloody album and ship it to the store. How hard is that?

But what did the music industry do?

- They hate running factories — which is hard work. So they tried to outsource manufacturing instead of building it themselves. Chronic shortages resulted.

- They refuse to spend money on R&D, so they stayed with the same vinyl technology from the 1950s. In other words, the record business became the only entertainment industry in the world with no plan for technological innovation. In the year 2023, even bowling alleys, bordellos, and bookies are more tech savvy than the major record labels.

- They want easy money, so they kept prices extremely high. That was bizarre because their R&D and catalog acquisition costs were essentially zero, and they could have priced vinyl aggressively. Instead they treated vinyl as a luxury product, even as they dreamed of it also becoming a mass market option. But you can’t do both without a careful market segmentation strategy — which the labels never even started thinking about.

- They love hype, so they focused on high visibility vinyl reissues, which look good in press releases, but couldn’t be bothered to make back catalog albums available. After a decade of the vinyl revival, they still hadn’t taken even basic steps in offering a wide product line.

This is a lazy strategy — and the exact opposite of what they should have done. And the results are, of course, predictable.

“The Commission has no power to find liability. Its report will not bind the government”

Donna Laframboise continues to cover the Emergencies Act inquiry submissions, including one from Queen’s University law professor Bruce Pardy:

A screenshot from a YouTube video showing the protest in front of Parliament in Ottawa on 30 January, 2022.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Shortly after the Emergencies Act commission finished listening to witnesses, he authored a grim opinion piece in the Toronto Sun.

His expectations are exceedingly low. In his words, the commission’s

mandate is not to rule on the legality of the government’s actions but to inquire into “the circumstances that led to the declaration being issued and the measures taken for dealing with the emergency”. The Commission has no power to find liability. Its report will not bind the government. The Commission is ritual, and the purpose of ritual is performance not outcome – to make it appear that there is accountability without having to provide it. [bold added]

Let us hope he’s mistaken, and that Commissioner Paul Rouleau has a pleasant surprise in store for us. Whatever happens, Pardy’s article provides a useful history lesson. It describes the series of events that prompted the use of similar legislation the last time around:

Between 1963 and 1970, the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) committed hundreds of bombings and several robberies, killing six people, including Quebec deputy premier Pierre Laporte. In response, Pierre Trudeau’s government invoked the War Measures Act.

Six murders – including the politically motivated kidnapping and execution of a deputy premier. Seven years of violence. Hundreds of bombings. Compare and contrast to the three-week festive, bouncy-castle, hot-tub trucker protest in which not a single person was robbed, bombed, or murdered.

Times sure have changed. Today, the same Canadian federal government that talks constantly about equity, diversity, and inclusion failed to do a single thing to make the protesting truckers feel as though their concerns, perspectives, or lives mattered. Diversity is something the government preaches, but doesn’t practice. Disagree with the Prime Minister and you’re a fringe minority with unacceptable views. Inclusion is a fancy word that makes politicians feel good about themselves, but it isn’t a principle that informs their actual behavour.

I thought the treadmill crane was fictional

Tom Scott

Published 26 Sep 2022The treadwheel crane, or treadmill crane, sounds like something from Astérix or the Flintstones. But at Guédelon in France, not only do they have one: they’re using it to help build their brand new castle.

▪ More about Guédelon: https://www.guedelon.fr/

(more…)