There is no more evanescent quality than modernity, a rather obvious or even banal observation whose import those who take pride in their own modernity nevertheless contrive to ignore. Having reached the pinnacle of human achievement by living in the present rather than in the past, they assume that nothing will change after them; and they also assume that the latest is the best. It is difficult to think of a shallower outlook.

Of course, in certain fields the latest is inclined to be best. For example, no one would wish to be treated surgically using the methods of Sir Astley Cooper: but if we want modern treatment, it is not because it is modern but because it better as gauged by pretty obvious criteria. If it were worse (as very occasionally it is), we should not want it, however modern it were.

Alas, the idea of progress has infected important spheres in which it has no proper application, particularly the arts. It is difficult to overestimate the damage that the gimcrack notion of teleology inhering in artistic endeavour has inflicted on all the arts, exemplified by the use of the term avant-garde: as if artists were, or ought to be, soldiers marching in unison to a predetermined destination. If I had the power to expunge a single expression from the vocabulary art criticism, it would be avant-garde.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Architectural Dystopia: A Book Review”, New English Review, 2018-10-04.

January 16, 2023

QotD: The avant-garde

January 2, 2023

December 29, 2022

QotD: That foolish optimism of the early days of the internet

Thirty years ago, at the dawn of what we think of as the internet, no one imagined that this amazing new frontier in human interaction would become a tool of oppression wielded by massive corporations. In fact, it was assumed that the internet would break the grip of corporations, special interests, and even governments. People would be free of the gatekeepers who controlled public discourse.

Those we call the left were sure that the internet would help democratize American society by opening the floor to marginalized voices. The people we call the right were sure this new medium would follow the pattern of talk radio. Free of progressive control, normal people could challenge the opinions of the liberal media. The internet was going to be an open debating society that worked on democratic principles.

Thirty years on and people old enough to remember the before times think that maybe the internet was a mistake. Giving a platform to millions of talking meat sticks, banging away at their phones, has just made life noisy. Worse yet, the range of allowable opinion has become much narrower. We now live in an age of censorship that was unimaginable before the internet.

The Z Man, “Coercion and Consensus”, Taki’s Magazine, 2022-09-25.

December 27, 2022

Whatever government touches, it makes worse – book publishing as a prime example

The Canadian government has always claimed to want to encourage Canadian book publishers and many, many speeches and press conferences and announcements and gestures have been produced over the years (not just by the Liberals, but usually by the Liberals). The actual results of all that political performance? “Meh” at the very best:

Another of my favorite SHuSHs of 2022 was no. 168, “It Started as Polite Talk”, in which my colleague Dan Wells of Biblioasis complained of the dominance of foreign publishers in the Canadian book market. “I don’t think there’s a literate nation in the world whose native industry makes up a small percentage of its overall market”, he said. “This, perhaps, is the real crisis of Canadian publishing.”

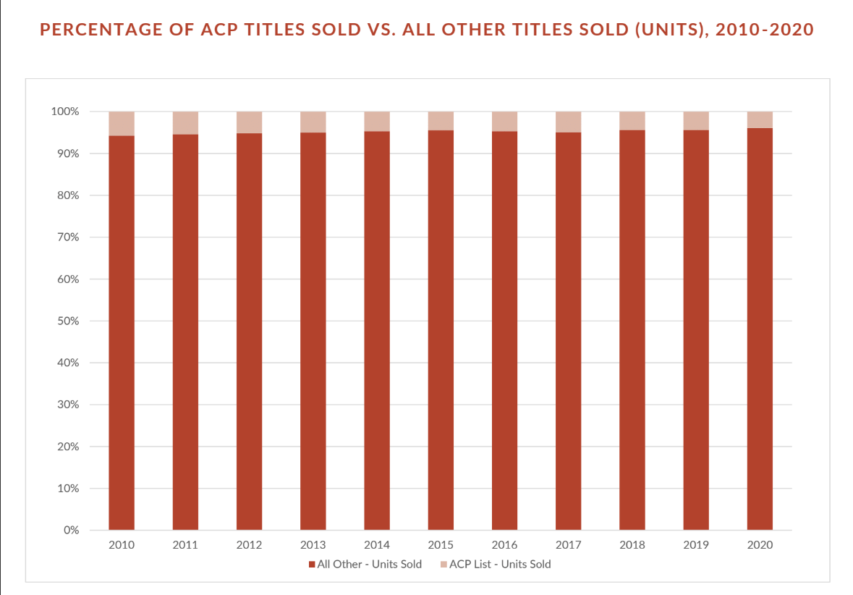

The astonishing thing to me is that the stated policy of the federal government for more than half a century has been to foster and protect a Canadian-owned publishing sector to avoid outsourcing our intellectual life to New York and London. Acres of policy written. Billions spent. The results are risible. Here’s a visual representation of Dan’s point. The 113 members of the Association of Canadian Publishers, representing the vast majority of English-language book publishers in Canada, produce $34 million in annual sales against the $1.1 billion of foreign firms:

If you read the self-congratulatory reports from the Department of Canadian Heritage and the Canada Council, everything is fine: “The Canadian book publishing industry consistently demonstrates a high degree of resilience.”

Does this look resilient to you?

I’ve never been much of a Canadian nationalist and, all things considered, I’d prefer less of a government presence in our arts sector, but government is now so deeply entrenched in book publishing and has made such a hash of the industry that there’s really no way out that doesn’t involve better government policy.

What, exactly, better policy might look like is next year’s project.

December 23, 2022

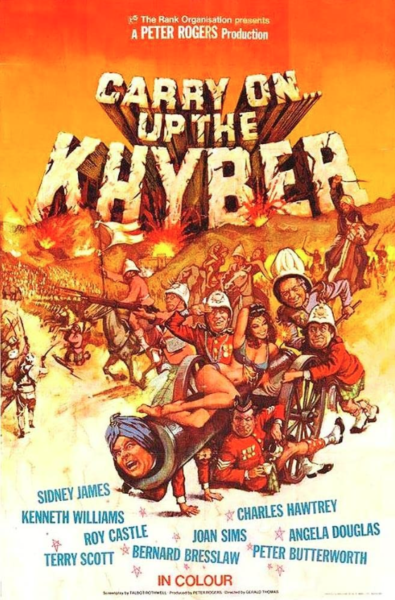

QotD: Wokeness as a lifestyle

The quick and dirty version is: Since the goddamn Boomers will never, ever retire — they’ll keep patting themselves on the back for Sticking It to the Man until they’re lowered into their tie-dyed, patchouli-reeking coffins, even though they’re all hedge fund managers and live in McMansions — the subsequent generations had to find a new area in which to compete for social status. Thus lifestyle striving for Gen X, and persona striving for the Millennials.

For Gen X, think of my personal candidate for “everything that’s wrong with the 90s, all in one place,” the 1994 movie Reality Bites. Don’t rent it unless you’re current on your blood pressure meds. It’s four of the 1990s’ most insufferable people (Winona Ryder, Ethan Hawke, Ben Stiller, Janeane Garofalo) quipping about being slackers. Well, except Stiller (also the director), who plays the grasping, uptight, sold-his-soul-to-The-Man yuppie foil to the other three. Stiller is the Gen Xer who chose to compete in the oversaturated career arena; he’s cartoonishly evil. The rest of them hang out in coffee houses, polishing their image. They’re lifestyle competitors.

For Millennials, and whatever we’re calling the upcoming generation (“The Lobotomized Snowflake Posse” is my suggestion, brevity be damned), well, just look at social media. Even lounging-around-Starbucks lifestyle competition is out of reach for people who went $100K in the hole for a Gender Studies degree. The only currency they’ve got is effort — hey, didn’t Karl Marx say something about that? — so Twitter becomes their full time job. Xzhe with the most followers wins.

Severian, “Why So #Woke?”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-01-07.

December 22, 2022

December 14, 2022

Point – “Society cannot be so radically changed”

Counterpoint – Western culture since 1960:

“The Pill” by starbooze is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0 .

The discussion of the causes of the problem is clear enough, whereas the discussion of possible solutions leaves much to be desired.

It seems to me rational to say that if the loss of family life was caused by the pill leading to abortion leading to the normalization of fornication, which in turn leads to ten percent of high-status males being sought by sixty percent of females, which in turn incentivizes fornication — because any woman unwilling to play the unpayed whore on the first date will be quickly replaced by one more willing — and if this in turn leads to a anti-child culture where the normal expectations and social support for mothers with children is lost, that therefore the solution is not to have maternal women try harder and made more sacrifices than the grandmothers were asked to make.

The solution is to normalize monogamy, which is impossible as long as contraception is not seen as the grave moral evil it is. Hence the solution, as soon as the culture atmosphere permits it, is to illegalize contraception.

After 1930 Lambeth Conference, the Anglicans spoke of contraception as permissible. The resolution, which passed 193 to 67 with 47 abstentions, is said to be the first instance where any responsible authority – not simply in Christendom but in any culture – had publicly supported, in any way at all, the use of artificial contraception.

Many other denominations followed suit and caved in on this issue.

The Roman Catholic Church teaches, and maintains, that contraception, in addition to being imprudent and damaging to the woman’s long-interests best interests, is a sin.

This is an ancient teaching which reaches back to the First Century. See, for example, the teaching manual of the Apostles, the Didache reads: “You shall not practice birth control, you shall not murder a child by abortion, nor kill what is begotten”. — Many scholars translate this as “practice sorcery” or “use potions” because the Greek word “pharmakon” (from which we get our word for pharmaceutical) sometimes has that meaning. However, it also means to use medicines, potions, or poisons, and the term was also used to refer to contraceptive measure, as it does here.

This is a core Christian teaching, and always has been.

The medical knowledge that chemical contraception, aka “the pill”, meddles with female hormones and induces depression and other mental disorders apparently is an insufficient motivator to reverse this poisonous addiction by the whole society.

Does returning to a society that respects women, follows wisdom, and disapproves of sex desecrated to mere recreation, and forbids our womenfolk to be degraded to harlots, seem impossible? Look around you. The sexual grooming of gradeschoolers and the surgical mutilation of their genitals due to sexual neurosis is a direct result of the sexual revolution, as is the abomination and absurdity of Orwellian gay marriage.

It may not be as impossible to convince the public that the alternative of happy marriages is so much less desirable than the hell of sexual self-mutilation, pornography, and perversion seen around us. It is not as if the Left will be satisfied with castration and mastectomy performed on children, once this is normalized. They will move on to the next thing, and after that, the next.

There is no final level. Hell is bottomless.

December 12, 2022

“The reason that Canada’s arts do not resonate with 95% of Canadians is that they are products of socialist realism’

Elizabeth Nickson on the parasitic world of official “Canadian culture” with its gatekeepers, subsidies, and luxury beliefs:

When I say society, I don’t mean the upper reaches of the wealthy. While we do have the very rich in Canada, they are rigorous in their hiddenness because we have the worst lefties on the continent and that is saying something. The safe thing for any wealthy family is give $ to socialists, bow and scrape to the harpies at the CBC and hope they don’t notice your bank balance. Anyway, these dreadful people arrived post WW2 with their hideous Frankfurt School ideas and just preyed on the simplest most innocent well-meaning good white people you could ever imagine, and literally ate, ravenous and braying all the while, the country’s potential.

So the scandal took place among them, or rather the world they created, which is basically a clutch of 150,000 grifters located between Ottawa, Toronto and Quebec City, whose only mission is to divest the government of as much public money as possible. This is particularly true of their defensive line which consists of the arts and journalism. Theirs is a world where no stone is left unsubsidized by taxes on the hidden rich, waitresses at truck stops in Kamloops and anyone who dares to make money unapproved by the CBC. They are, as a former editor swore to me, the gatekeepers. That was before her circulation collapsed by 65%., but no doubt she still believes it.

The arts and media in Canada are constructed entirely for the 5%, consumed by those who live the lush subsidized life — or those who want to — whether in government or in semi-independent corporations or businesses who require government help and “seed” money etc. (There are a hundred terms for the grift.)

Books, if you look at their sales, are tragic. There have been a handful of impressive films, despite the literal billions thrown at filmmakers over the past 20 years. Most of them are catastrophically depressing, the books make you want to cut out your heart with a grapefruit spoon. Painters paint, if you subtract all the hectoring from minor artists, from forced inclusion, some of them are very good. We can create good art. But not with our current curators.

The reason that Canada’s arts do not resonate with 95% of Canadians is that they are products of socialist realism. They describe humans and human life as they either believe it to have been (dark and in need of enlightened beings like themselves) or as they feel it must be in the future (filled with people expressing their oppression and being paid for it). It’s basically fantasy, and no one likes it, watches it, reads it.

The rest of Canada is a centre-right country, a gut-it-out-and-build-it-kind of place. I know that is the exact opposite of the propaganda, but Conservatives win a majority of the votes in every election, yet still only amount to 40%. We have five parties, and four of them are leftie — their platforms are all “more money for us” — but the big party, the one that receives about 30% of the vote is so crafty, so embedded in our vast vast bureaucracy that fixing the game is child’s play. Informed by their Frankfurt School gurus, they have been in power 100 years, with brief Conservative interludes.

We take in about half a million immigrants a year, and most of them are from desperate places. Vote harvesting in those neighborhoods is done by leaders in each immigrant community. These men and women are the strongest, most educated and frankly from the ones I’ve met, thuggish, and through them comes all access to government programs, housing and education. Therefore, when they collect your vote, you know for whom your vote is meant. The thing about immigrants though is that they were coming for the old Canada, not the new Commie police state.

But for now? Easy. No one investigates this. Why not? Our media is subsidized. ALL of it.

December 10, 2022

Ed West finds nice-ish things to say about the French

It’s actually part two, which I’m sure would astonish many a Brit:

The Royal Standard of the King of France (and by default, the national flag), used between 1638 and 1790.

Wikimedia Commons.

“When, after their victory at Salamis, the generals of the various Greek states voted the prizes for distinguished individual merit, each assigned the first place of excellence to himself, but they all concurred in giving their second votes to Themistocles,” wrote the great 19th-century historian Edward Creasy. “This was looked on as a decisive proof that Themistocles ought to be ranked first of all. If we were to endeavour, by a similar test, to ascertain which European nation has contributed the most to the progress of European civilization, we should find Italy, Germany, England, and Spain, each claiming the first degree, but each also naming France as clearly next in merit. It is impossible to deny her paramount importance in history.”

France is central to the story of Europe, and indeed of Britain. It is almost impossible to understand England’s history without appreciating the relationship with its closest continental neighbour. It is a love-hate affair originating in a grand inferiority complex, a long rivalry that continues tomorrow [Saturday] when England meet France in the World Cup quarter-finals.

In a piece last year I cited some of the most endearing/maddening things about the French, all of which contributed to a sense of amused frustration on our part:

Only in France would football fans protest that a local restaurant had lost a Michelin Star, as happened in Lyon two years ago. Only in France would an expedition to the Himalayas — of huge national importance — fail because it was weighed down by eight tonnes of supplies, including 36 bottles of champagne and “countless” tins of foie gras. And only in France would you get actual wine terrorists, the Comité Régional d’Action Viticole, who have bombed shops, wineries and other things responsible for importing foreign produce. This is a country which only reluctantly in the 1950s stopped giving school children a nutritious drink for their health, by which the French meant not milk but cider.

This is a country where mistresses are so much part of life that they can legally inherit, and where murder doesn’t really count if it’s done for love. One of France’s most famous socialites, Henriette Caillaux, shot dead the editor of Le Figaro just before the First World War and received just four months in jail because it was a crime passionnel. So that’s all right then.

But there are so many other things to love about our strange neighbours …

The Anglo-French relationship is a difficult one, reflected in the troubled history of royal marriages. Charles I’s Catholic wife Henrietta Maria was a drag on his popularity among excitable Protestant radicals, and turned out to be the last French consort; in the 14th century Edward II’s wife Isabella overthrew him and, perhaps, conspired to have him killed, after a rocky marriage that began badly when he brought his lover to the coronation and acted inappropriately affectionate towards him. But then, as Edith Cresson pointed out, this is to be expected when you marry an Englishman.

In 1514 Louis XII married an English bride, Henry VIII’s sister Mary; she was 18, he was 53, and had syphilis, so she must have been delighted about the whole thing; however, within weeks she had “danced him to death”, the sex apparently proving too exciting for his nervous system. Francesco Vettori, Florence’s ambassador to Rome, wrote that King Louis had a lady “so young, so beautiful and so swift that she had ridden him right out of the world”.

***

Perhaps not a terrible way for a Frenchman to go, and not the last French head of state to die in a similar manner. President Félix Faure expired in 1899 while with his mistress, after which his funeral featured this very understated carriage.

***

Numerous French presidents have had affairs, although Francois Mitterrand actually had a secret second family while in the Élysée Palace. Mitterrand’s last meal was also ultra-French: “He’d eaten oysters and foie gras and capon — all in copious quantities — the succulent, tender, sweet tastes flooding his parched mouth. And then there was the meal’s ultimate course: a small, yellow-throated songbird that was illegal to eat. Rare and seductive, the bird — ortolan — supposedly represented the French soul. And this old man, this ravenous president, had taken it whole — wings, feet, liver, heart. Swallowed it, bones and all. Consumed it beneath a white cloth so that God Himself couldn’t witness the barbaric act.”

***

The French are world outliers in their attitudes to adultery, the only country where a majority of people think it’s fine. Germany is number two in this index of permissiveness while the Americans, of course, are the most disapproving western nation.

December 3, 2022

The end of the old “WASP” upper class

Scott Alexander is reading Bobos in Paradise by David Brooks and summarized the first sixth of the book:

The daring thesis: a 1950s change in Harvard admissions policy destroyed one American aristocracy and created another. Everything else is downstream of the aristocracy, so this changed the whole character of the US.

The pre-1950s aristocracy went by various names; the Episcopacy, the Old Establishment, Boston Brahmins. David Brooks calls them WASPs, which is evocative but ambiguous. He doesn’t just mean Americans who happen to be white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant — there are tens of millions of those! He means old-money blue-blooded Great-Gatsby-villain WASPs who live in Connecticut, go sailing, play lacrosse, belong to country clubs, and have names like Thomas R. Newbury-Broxham III. Everyone in their family has gone to Yale for eight generations; if someone in the ninth generation got rejected, the family patriarch would invite the Chancellor of Yale to a nice game of golf and mention it in a very subtle way, and the Chancellor would very subtly apologize and say that of course a Newbury-Broxham must go to Yale, and whoever is responsible shall be very subtly fired forthwith.

The old-money WASPs were mostly descendants of people who made their fortunes in colonial times (or at worst the 1800s); they were a merchant aristocracy. As the descendants of merchants, they acted as standard-bearers for the bourgeois virtues: punctuality, hard work, self-sufficiency, rationality, pragmatism, conformity, ruthlessness, whatever made your factory out-earn its competitors.

By the 1950s they were several generations removed from any actual hustling entrepreneur. Still, at their best the seed ran strong and they continued to embody some of these principles. Brooks tentatively admires the WASP aristocracy for their ethos of noblesse oblige — many become competent administrators, politicians, and generals. George H. W. Bush, scion of a rich WASP family, served with distinction in World War II — the modern equivalent would be Bill Gates’ or Charles Koch’s kids volunteering as front-line troops in Afghanistan.

At their worst, they mostly held ultra-expensive parties, drifted into alcoholism, and participated in endless “my money is older than your money” dick-measuring contests. And they were jocks — certainly good at lacrosse and crew, but their kids would be much less likely than modern elites’ to become a scientist, professor, doctor, or lawyer. Not only that, they were boring jocks — they stuck to a few standard rich people hobbies (yachting, horseback riding) and distrusted creativity or (God forbid) quirkiness. Their career choices were limited to the family business (probably a boring factory with a name like Newbury-Broxham Goods), becoming a competent civil service administrator, or other things along those lines.

The heart of the WASP aristocracy was the Ivy League. I don’t think there are good statistics, but until the early 1900s many (most?) Ivy League students were WASP aristocrats from a few well-known families. Around 1920 the Jews started doing really well on standardized tests, and the Ivies suspended standardized tests in favor of “holistic admissions” to keep them out and preserve the WASPishness of the elite. All the sons (and later, daughters) of the WASPs met each other in college, played lacrosse together, and forged the sort of bonds that make a well-connected and self-aware aristocracy.

Around 1955 (Brooks writes, building on an earlier book by Nicholas Lemann) Harvard changed their admission policy. Why? Partly a personal decision by Harvard presidents James Conant, and Nathan Pusey, who sincerely believed in meritocracy. And partly because Harvard’s Jewish quota was becoming unpopular, as increased awareness of the Holocaust made anti-Semitism déclassé. Conant and Pusey decided to admit based on academic merit (measured mostly by SAT scores). The thing where Harvard would always admit WASP aristocrats because that was the whole point of Harvard was relegated to occasional “legacy admissions”, a new term for something which was now the exception and not the rule. Other Ivies quickly followed.

Brooks on the consequences:

In 1952, most freshmen at Harvard were products of … the prep schools of New England (Andover and Exeter alone contributed 10% of the class), the East side of Manhattan, the Main Line of Philadelphia, Shaker Heights in Ohio, the Gold Coast of Chicago, Grosse Pointe of Detroit, Nob Hill in San Francisco, and so on. Two-thirds of all applicants were admitted. Applicants whose fathers had gone to Harvard had a 90% admission rate. The average verbal SAT score for the incoming men was 583, good but not stratospheric. The average score across the Ivy League was closer to 500 at the time.

Then came the change. By 1960 the average verbal SAT score for incoming freshman at Harvard was 678, and the math score was 695 — these are stratospheric scores. The average Harvard freshman in 1952 would have placed in the bottom 10% of the Harvard freshman class of 1960. Moreover, the 1960 class was drawn from a much wider socioeconomic pool. Smart kids from Queens or Iowa or California, who wouldn’t have thought of applying to Harvard a decade earlier, were applying and getting accepted … and this transformation was replicated in almost all elite schools. At Princeton in 1962, for example, only 10 members of the 62-man football team had attended private prep schools. Three decades earlier every member of the Princeton team was a prep school boy.

There was a one-or-two generation interregnum where the new meritocrats silently battled the old WASP aristocracy. This wasn’t a political or economic battle; as a war to occupy the highest position in the class hierarchy, it could only be won through cultural prestige. What was cool? What was out of bounds? What would get printed in the New York Times — previously the WASP aristocracy’s mouthpiece, but now increasingly infiltrated by the more educated newcomers?

November 26, 2022

Indigo vastly prefers selling pillows, candles, and tchotchkes of all kinds rather than – ugh! – books

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte explains why it’s becoming harder and harder to find actual books in Canada’s biggest bookstore chain … because they no longer want to be a bookstore chain:

“Indigo Books and Music” by Open Grid Scheduler / Grid Engine is licensed under CC0 1.0

We need to talk about Indigo. As you know, it’s Canada’s biggest bookstore chain, with 88 superstores and 85 small-format stores. It sells well over half the books that are bought in stores in Canada, with Walmart, Costco, and independent bookstores accounting for most of the rest.

One problem with Indigo is that it’s failing. The other problem is that it’s abandoning bookselling. Yes, that sounds like a Woody Allen joke, but it’s not funny from a publishing perspective. We depend on Indigo.

The company’s finances have been ugly for some time. It lost $37 million in 2019, $185 million in 2020, and $57 million in 2021. Things looked somewhat better in 2022 with a $3 million profit, but the first two quarters of 2023 are now in the books (it has a March 28 year end) and Indigo has already dropped $41.3 million.

[…]

Indigo hasn’t come right out and said we’re through with books. It can’t, given that Heather [Reisman] has spent the last twenty-five years building herself up as the queen of reading in Canada. Also, the Indigo brand is still associated with books in most people’s minds and that won’t change overnight no matter how many cheeseboards it stocks. So Heather talks about a gradual, natural transition: “We built a wonderful connection with our customers in the book business. Then, organically, certain products became less relevant and others were opportunities.”

To be clear, books are irrelevant; general merchandise is the opportunity. Heather recently appointed as CEO a guy named Peter Ruis who has no experience in books. He comes from fashion retail, most recently the Anthropologie chain, which sells clothing, shoes, accessories, home furnishings, furniture, and beauty products. Anthropologie was hot in 2008, and it seems to be where Indigo wants to go today.

Fair enough. You own a company, you can take it in any direction you want, so long as your shareholders will follow. I don’t blame Heather for having second thoughts about the book business. (I have them every week. It’s a tough business.) But where does that leave readers, writers, agents, publishers, and everyone else who remains committed to books?

You’ll recall that Indigo and Chapters, between them, decimated the independent bookselling sector in Canada in the nineties. They are the principal reason Canada has so few independent bookstores today. You could probably fit the combined stock of all our independents into a handful of Heather’s stores.

The federal government let Heather’s Indigo buy Larry Stevenson’s Chapters in 2001, which gave her a ridiculously large share of the market. That shouldn’t have happened.

At the same time, with the help of some lobbying by Heather, the federal government made it clear that the US chains, Borders and Barnes & Noble, weren’t welcome up here. The argument was that bookselling was a crucial part of our cultural sector and needed to be protected from foreign domination by the Canadian government.

In that spirit, Indigo also asked the federal government to prevent Amazon from opening warehouses in Canada. That request was denied in 2010, which is about when Indigo began its transition out of books.

One can see how Heather might feel betrayed by the federal government. Instead of protecting bookselling, it swung the door wide open for Amazon. You said I wouldn’t have to compete!

November 18, 2022

QotD: Therapism

Therapism has caused a decline in the quality of our culture. People are now engaged in a kind of arms race, feeling obliged to express their emotions ever more extravagantly to prove to themselves and other just how much and how deeply they feel. This leads to the peculiar shrillness, shallowness, and lack of subtlety of so much of our culture.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Bad counsel”, The New Criterion, 2005-06-23.

November 13, 2022

Carrying on about the Carry On movies

In The Critic, Alexander Larman looks back at one of the longest-running film series beginning with 1958’s Carry On Sergeant (not to be confused with the earlier — and reputedly terrible — interwar Canadian film of the same name) and continuing with many more until the filmic disaster of Carry On Emmanuelle in 1978 (there was also a 1992 attempt to revive the franchise, which failed):

In Alan Bennett’s The History Boys, it is decreed by the contrarian history master, Irwin, that “if George Orwell had lived, nothing is more certain than that he would have written an essay on the Carry On films”.

We are invited to take Irwin’s instructions that the Carry On films represent a valuable insight into British social history with suitable detachment. (The precise, suitably pompous quote is that “while they have no intrinsic merit, they acquire some of the permanence of art simply by persisting, and acquire an incremental significance if only as social history”.)

Yet Irwin (or Bennett) was almost certainly right that, had Orwell survived into the Sixties and Seventies, he would have found the Carry On film series both repellent and fascinating. It is literature’s, and history’s, loss that we do not have an account of Orwell’s thoughts on the antics of Charles Hawtrey, Kenneth Williams, Barbara Windsor et al.

In 1941, Orwell wrote of postcards by the cheerfully lowbrow artist Donald McGill that “your first impression is one of overpowering vulgarity” and that “what you are really looking at is something as traditional as Greek tragedy, a sort of sub-world of smacked bottoms and scrawny mothers-in-law which is a part of Western European consciousness”. He goes on to say that “jokes barely different from McGill’s could casually be uttered between the murders in Shakespeare’s tragedies”.

[…]

The joy of watching the Carry On films, then, is twofold. On the one hand, the hackneyed stories, two-dimensional characterisation and laboured puns and innuendo can be enjoyable, on a purely basic level, but hardly threaten to aspire to the levels of great art.

Yet on the other, the cheerfully Rabelaisian sentiments of the pictures — in which all men and women are defined purely in sexual and scatological terms — exist on a level of reductio ad absurdum.

It is no coincidence that the best Carry On films contain a vein of social satire in their mocking of great British institutions, whether it be the NHS, MI5, the army or the Raj, and the final set piece of Carry On Up The Khyber — in which the stiff-upper-lip British occupiers ignore the Afghan invaders while taking formal dinner in black tie — rises to a level of surrealist genius that would have made Buñuel proud.

There is occasional talk of making another Carry On film, but with all the principal cast (save the ever-sprightly Dale) now dead and with the world a very different place, it is impossible to imagine that we will ever see, say, Carry On Tweeting or the like.

There is every possibility that a really top-notch cast could be assembled, if there was any serious intent behind it — I would love to see Andrew Scott, for instance, offer a more dynamic take on the kind of roles that Williams essayed, because he would do so brilliantly, and if the script could be written by the award-winning likes of Patrick Marber or Richard Bean, it could be a thing of innuendo-heavy beauty.

But then the Carry On series never was a thing of beauty. In its grim and hilarious way, it took every British national stereotype, pulled its trousers down, and gave it a hearty slap on its bare buttocks. Some might find this offensive; others might mourn its loss from public life.

In either case, we shall not look upon its like again. Dr Nookey, Francis Bigger, Professor Inigo Tinkle, Vic Flange: your services are no longer required. To which unkind cut we must solemnly say: “Ooh, matron.”

October 24, 2022

The rise of “Queer Theory”

In City Journal, Christopher F. Rufo provides the background that has lead to the widespread phenomenon of “Drag Queen Story Hour”:

Start with queer theory, the academic discipline born in 1984 with the publication of Gayle S. Rubin’s essay “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality”. Beginning in the late 1970s, Rubin, a lesbian writer and activist, had immersed herself in the subcultures of leather, bondage, orgies, fisting, and sado-masochism in San Francisco, migrating through an ephemeral network of BDSM (bondage, domination, sadomasochism) clubs, literary societies, and New Age spiritualist gatherings. In “Thinking Sex”, Rubin sought to reconcile her experiences in the sexual underworld with the broader forces of American society. Following the work of the French theorist Michel Foucault, Rubin sought to expose the power dynamics that shaped and repressed human sexual experience.

“Modern Western societies appraise sex acts according to a hierarchical system of sexual value,” Rubin wrote. “Marital, reproductive heterosexuals are alone at the top erotic pyramid. Clamouring below are unmarried monogamous heterosexuals in couples, followed by most other heterosexuals. … Stable, long-term lesbian and gay male couples are verging on respectability, but bar dykes and promiscuous gay men are hovering just above the groups at the very bottom of the pyramid. The most despised sexual castes currently include transsexuals, transvestites, fetishists, sadomasochists, sex workers such as prostitutes and porn models, and the lowliest of all, those whose eroticism transgresses generational boundaries.”

Rubin’s project — and, by extension, that of queer theory — was to interrogate, deconstruct, and subvert this sexual hierarchy and usher in a world beyond limits, much like the one she had experienced in San Francisco. The key mechanism for achieving this turn was the thesis of social construction. “The new scholarship on sexual behaviour has given sex a history and created a constructivist alternative to” the view that sex is a natural and pre-political phenomenon, Rubin wrote. “Underlying this body of work is an assumption that sexuality is constituted in society and history, not biologically ordained. This does not mean the biological capacities are not prerequisites for human sexuality. It does mean that human sexuality is not comprehensible in purely biological terms.” In other words, traditional conceptions of sex, regarding it as a natural behavior that reflects an unchanging order, are pure mythology, designed to rationalize and justify systems of oppression. For Rubin and later queer theorists, sex and gender were infinitely malleable. There was nothing permanent about human sexuality, which was, after all, “political”. Through a revolution of values, they believed, the sexual hierarchy could be torn down and rebuilt in their image.

There was some reason to believe that Rubin might be right. The sexual revolution had been conquering territory for two decades: the birth-control pill, the liberalization of laws surrounding marriage and abortion, the intellectual movements of feminism and sex liberation, the culture that had emerged around Playboy magazine. By 1984, as Rubin acknowledged, stable homosexual couples had achieved a certain amount of respectability in society. But Rubin, the queer theorists, and the fetishists of the BDSM subculture wanted more. They believed that they were on the cusp of fundamentally transforming sexual norms. “There [are] historical periods in which sexuality is more sharply contested and more overtly politicized,” Rubin wrote. “In such periods, the domain of erotic life is, in effect, renegotiated.” And, following the practice of any good negotiator, they laid out their theory of the case and their maximum demands. As Rubin explained: “A radical theory of sex must identify, describe, explain, and denounce erotic injustice and sexual oppression. Such a theory needs refined conceptual tools which can grasp the subject and hold it in view. It must build rich descriptions of sexuality as it exists in society and history. It requires a convincing critical language that can convey the barbarity of sexual persecution.” Once the ground is softened and the conventions are demystified, the sexual revolutionaries could do the work of rehabilitating the figures at the bottom of the hierarchy — “transsexuals, transvestites, fetishists, sadomasochists, sex workers”.

Where does this process end? At its logical conclusion: the abolition of restrictions on the behavior at the bottom end of the moral spectrum — pedophilia. Though she uses euphemisms such as “boylovers” and “men who love underaged youth”, Rubin makes her case clearly and emphatically. In long passages throughout “Thinking Sex”, Rubin denounces fears of child sex abuse as “erotic hysteria”, rails against anti–child pornography laws, and argues for legalizing and normalizing the behavior of “those whose eroticism transgresses generational boundaries”. These men are not deviants, but victims, in Rubin’s telling. “Like communists and homosexuals in the 1950s, boylovers are so stigmatized that it is difficult to find defenders for their civil liberties, let alone for their erotic orientation,” she explains. “Consequently, the police have feasted on them. Local police, the FBI, and watchdog postal inspectors have joined to build a huge apparatus whose sole aim is to wipe out the community of men who love underaged youth. In twenty years or so, when some of the smoke has cleared, it will be much easier to show that these men have been the victims of a savage and undeserved witch hunt.” Rubin wrote fondly of those primitive hunter-gatherer tribes in New Guinea in which “boy-love” was practiced freely.

Such positions are hardly idiosyncratic within the discipline of queer theory. The father figure of the ideology, Foucault, whom Rubin relies upon for her philosophical grounding, was a notorious sadomasochist who once joined scores of other prominent intellectuals to sign a petition to legalize adult–child sexual relationships in France. Like Rubin, Foucault haunted the underground sex scene in the Western capitals and reveled in transgressive sexuality. “It could be that the child, with his own sexuality, may have desired that adult, he may even have consented, he may even have made the first moves,” Foucault once told an interviewer on the question of sex between adults and minors. “And to assume that a child is incapable of explaining what happened and was incapable of giving his consent are two abuses that are intolerable, quite unacceptable.”

Rubin’s American compatriots made the same argument even more explicitly. Longtime Rubin collaborator Pat Califia, who would later become a transgender man, claimed that American society had turned pedophiles into “the new communists, the new niggers, the new witches”. For Califia, age-of-consent laws, religious sexual mores, and families who police the sexuality of their children represented a thousand-pound bulwark against sexual freedom. “You can’t liberate children and adolescents without disrupting the entire hierarchy of adult power and coercion and challenging the hegemony of antisex fundamentalist religious values,” she lamented. All of it — the family, the law, the religion, the culture — was a vector of oppression, and all of it had to go.

October 18, 2022

“On average, a twenty-five year old man has the same level of impulse control as a 10 year old girl”

Rob Henderson considers how early humans managed to overcome violent tendencies as human communities got larger, and specifically considers the social role of young men, then and now:

One challenge to overcome involves the behavioral tendencies of young males.

[Oxford evolutionary psychologist Robin] Dunbar writes:

When males (and younger males, in particular) are deprived of social, economic, and mating opportunities, they are prone to behaving in ways that both stress other group members (especially reproductive females) and threaten the stability and cohesion of the group. This is as true of the more social primates as it is of humans, and is often associated with high mortality rates. Under these circumstances, males are also likely to indulge in raiding neighbouring groups, which can result in poor inter-community relations as well as retaliation. Managing male behaviour may, thus, be critical to maintaining an environment conducive to successful reproduction.

Young males are (unknowingly) experts at disrupting social cohesion. To be fair, they are also required to maintain and defend it. They’re a mixed bag.

Disputes that spill over into violence and homicide have been an ever-present risk in both contemporary and pre-modern small scale societies. Young men make up the overwhelming majority of such conflicts, both as perpetrators and as victims.

[…]

The vast majority of violence is carried out by young men.

Psychologically, a key reason for this is that women are more sensitive than men to penalties. Men are more inclined to take risks, oblivious to the punishments they may receive. Men also have lower levels of empathy and a higher tolerance for pain.

The psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen has posited the hypothesis of the “extreme male brain”, suggesting that males are at higher risk for a clinical diagnosis of autism because of the constellation of traits men tend to score higher on (e.g., systematizing over empathizing, favoring things over people, etc). It also implies that most males may be a little bit autistic. Of course, some women score highly on these traits, and there are girls and women who are diagnosed with autism. Just at much lower rates than males.

I have wondered if, in addition to autism, the idea of the “extreme male brain”, could just as easily apply to psychopathy.

For both psychopathy and autism, the ratio of males to females is about three to 1.

Men (especially young men) are more pronounced than women on just about every trait that characterizes psychopathy.

Relatively low impulse control, low empathy, low fear, high sensation seeking, relatively shallow emotions, need for stimulation, proneness to boredom, violent fantasies, desire for revenge, and increased likelihood of criminality. Of course, some women score highly on these traits, and there are women who are psychopaths. But far fewer than males.

The psychologist John Barry has pointed out that when he was a student, he learned he couldn’t use standard adult psychopathy tests to administer to teenage boys. The reason? Because adult tests might give teen males a false positive.

Just as (relative to women) most men might be a little bit autistic, most (young) men might be a little bit psychopathic.

On average, a twenty-five year old man has the same level of impulse control as a 10 year old girl.