Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published Jul 17, 2024Episode Three: Now that Caesar has crossed the Rubicon, the Civil War has begun and the series gathers pace.

Vidcaps taken from the dvd collection and copyright belongs to the respective makers and channels.

Transcript

November 18, 2024

HBO’s Rome Ep. 3 “The owl in a thorn bush” – History and Story

November 17, 2024

Contrasting origin stories – the 13 Colonies versus the “Peaceful Dominion”

At Postcards From Barsoom, John Carter outlines some of the perceived (and real) differences in the origin stories of the United States and Canada and how they’ve shaped the respective nations’ self-images:

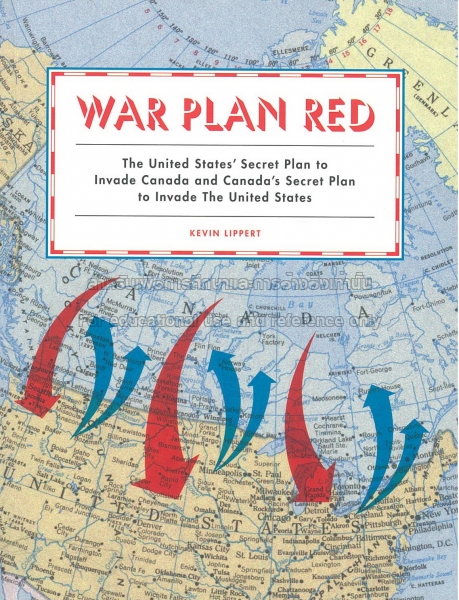

The US had plans to invade Canada that were updated as recently as the 1930s (“War Plan Crimson”, a subset of the larger “War Plan Red” for conflict with the British Empire). Canada also had a plan for conflict with the US, although it fell far short of a full-blooded invasion to conquer the US, designated as “Defence Scheme No. 1”, developed in the early 1920s.

In perennial contrast to its tumultuous southern neighbour, Canada has the reputation of being an extremely boring country.

America’s seeds were planted by grim Puritans seeking a blank slate on which to inscribe the New Jerusalem, and by aristocratic cavaliers who wanted to live the good life while their slaves worked the plantations growing cash crops for the European drug trade. The seeds of America’s hat were planted by fur traders gathering raw materials for funny hats.

America was born in the bloody historical rupture of the Revolutionary War, casting off the yoke of monarchical tyranny in an idealistic struggle for liberty. Canada gained its independence by politely asking mummy dearest if it could be its own country, now, pretty please with some maple syrup on top.

America was split apart in a Civil War that shook the continent, drowning it in an ocean of blood over the question of whether the liberties on which it was founded ought to be extended as a matter of basic principle to the negro. Canada has never had a civil war, just a perennial, passive-aggressive verbal squabble over Quebec sovereignty.1

America’s western expansion was known for its ungovernable violence – cowboys, cattle rustlers, gunslingers, and Indian wars. Canada’s was careful, systematic, and peaceful – disciplined mounties, stout Ukrainian peasants, and equitable Indian treaties.

Once its conquest of the Western frontier was wrapped up, America burst onto the world stage as a vigorous imperial power, snatching islands from the Spanish Empire, crushing Japan and Germany beneath the spurred heel of its cowboy boot, and staring down the Soviet Union in the world’s longest high-stakes game of Texas Hold’Em. Canada, ever dutiful, did some stuff because the British asked nicely, and then they went home to play hockey.

America gave the world jazz music, rock and roll, and hip-hop; Canada contributed Celine Dion and Stan Rogers. America has Hollywood; Canada, the National Film Board and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. America dressed the world in blue jeans and leather jackets; Canadians, flannel and toques. America fattened the people with McDonald’s; Canada burnt their tongues with Tim Horton’s, eh.2

The national stereotypes and mythologies of the preceding paragraphs aren’t deceptive, per se. Stereotypes are always based in reality; national mythologies, as with any successful mythology, need to be true at some level in order to resonate with the nations that they’re intended to knit together. Of course, national mythologies usually leave a few things out, emphasizing or exaggerating some elements at the expense of others in the interests of telling a good story. Revisionists, malcontents, and subversives love to pick at the little blind spots and inconsistencies that result in order to spin their own anti-narratives, intended as a rule to dissolve rather than fortify national cohesion and will. Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States is a good example of this kind of thing, as is Nikole Hannah-Jones’ tendentious 1619 Project.

Probably the most immediately obvious difference between Americans and Canadians is that Americans don’t suffer from a permanent identity crisis. Demographic dilution due to decades of mass immigration notwithstanding, Americans by and large know who they are, implicitly, without having to flagellate themselves with endless introspective navel-gazing about what it means to be an American. The result of this is that most American media isn’t self-consciously “American”; there are exceptions, of course, such as the occasional patriotic war movie, but for the most part the stories Americans tell are just stories about people who happen to be American doing things that happen to be set in America. Except when the characters aren’t American at all, as in a historical epic set in ancient Rome, or aren’t set in America, as in a science fiction or fantasy movie. That basic American self-assurance in their identity means that Americans effortlessly possess the confidence to tell stories that aren’t about America or Americans at all, as a result of which Hollywood quietly swallowed the entire history of the human species … making it all American.

As Rammstein lamented, We’re All Living in Amerika …

Since we’re all living in Amerika, the basic background assumptions of political and cultural reality that we all operate in are American to their very core. Democracy is good, because reasons, and therefore even de facto dictators hold sham elections in order to pretend that they are “presidents” or “prime ministers” and not czars, emperors, kings, or warlords. Insofar as other countries compete with America, it’s by trying to be more American than the Americans: respecting human rights more; having freer markets; making Hollywood movies better than Hollywood can make them; playing heavy metal louder than boys from Houston can play it. It’s America’s world, and we’re all just along for the ride.

America’s hat, by contrast, is absolutely culturally paralyzed by its own self-consciousness … as a paradoxical result of which, its consciousness of itself has been almost obliterated.

Canada’s origin – the origin of Anglo-Canada, that is – was with the United Empire Loyalists who migrated into the harsh country of Upper Canada in the aftermath of the Revolutionary War. As their name implies, they defined themselves by their near-feudal loyalty to the British Crown. Where America was inspired by Enlightenment liberalism, Canada was founded on the basis of tradition and reaction – Canada explicitly rejected liberalism, offering the promise of “peace, order, and good government” in contrast to the American dream of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”.

1. Quebec very nearly left the country in a narrow 1995 referendum in which 49.5% of the province’s population voted to separate. It is widely believed in Anglo Canada that had the rest of the country been able to vote on the issue, Quebec would be its own country now.

2. Well actually a Brazilian investment firm has Timmies, but anyhow.

November 10, 2024

The Sixties, Cicero, Catiline, Cato and Caesar – The Conquered and the Proud Episode 9

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published Jul 3, 2024Continuing our series on the the history of Rome from 200 BC to AD 200, this time we look at the turbulent decade following the consulship of Pompey and Crassus in 70 BC. These years saw Pompey being given major commands against the pirates and Mithridates. Men like Cicero, Caesar and Cato were on the ascendant. Cicero’s letters can make the decade seem calm, but further consideration reveals the threat and reality of political violence, seen most of all in Catiline’s conspiracy which led to a brief civil war.

In this talk we explore the themes we have already considered and consider how imperial expansion continued to change the Roman Republic.

This talk will be released in July — and as this is the month named after Julius Caesar, it seemed only appropriate to have a Caesar theme to most of the talks.

Next time we will look at the Fifties BC and the start of the Civil War in 49 BC.

October 27, 2024

QotD: Puritans, predestination, and the Ranters

The third problem with Puritan wokeness is that it sinister echoes in the history of predestination. When the creed reached its zenith in the seventeenth century, the logical hole at its centre became insanely obvious. If it does not matter to God how you behave, because your salvation was pre-determined at birth, why not behave however the hell you want to?

The outpourings of radical thought in the English Civil Wars included sects who came to exactly this conclusion. The Ranters, at least by reputation, advocated a lifestyle of Dionysiac excess. If orgies and boozing, gluttony and blasphemy did not have any material impact on whether you were going to heaven or hell, then why not shag, indulge and curse the Lord as much as you want?

The extent of their membership is disputed and the fear of the Ranters was strong among the Puritans, partly, I suspect, because the logical fallacy of the original tenet is so glaringly obvious. Many of the theological arguments espoused by the men who were labelled Ranters were more textured and complicated than a license to loucheness. But the essential point remains: if you are already damned, your actions and intent are irrelevant.

The Puritan response was a horrified recoil. If God has made you one of the elect, you have a responsibility to Him to behave as if you are elect. A rare few came to believe they were not elect, and tortured themselves with it. If this sounds familiar, you have probably met an apologetic white male ally of the woke.

Antonia Senior, “Identity politics is Christianity without the redemption”, UnHerd, 2020-01-20.

September 30, 2024

Sulla, civil war, and dictatorship

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published Jun 5, 2024The latest instalment of the Conquered and the Proud looks at the first few decades of the first century BC. We deal with the final days of Marius, the rise of Sulla, the escalating spiral of civil wars and massacres as Rome’s traditional political system starts breaking down.

Primary Sources – Plutarch, Marius, Sulla, Pompey, Crassus, Cicero and Caesar. Appian Civil Wars and Mithridatic Wars.

Secondary (a small selection) –

P. Brunt, Social Conflicts in the Roman Republic & The Fall of The Roman Republic

A. Keaveney, Sulla – the last Republican

R. Seager, Pompey the Great: A political Biography

September 1, 2024

QotD: “Yellow China” versus “Blue China”

This whole period often gets referred to as the “Chinese Middle Ages”, and unlike the European Middle Ages1 it’s been scandalously neglected by Western historians (with the exception of some of the Tang stuff). This is a shame, because so many of the most important themes of Chinese history got their start during this period, I’ll mention two of them here.

The first is the polarity between North and South or, if you want to sound pretentious, between “Yellow China” and “Blue China”. “Yellow” represents the sandy but fertile yellow loess soil of the North China Plain and the Yellow River valley, heartland of traditional Chinese civilization. But “yellow” is also the ripe ears of grain that grow in that soil, because the North is a land fed by wheat rather than rice. “Yellow” also, by extension, refers to the mass irrigation projects required to make the arid North bloom, to the taxation and slave labor required to dredge and maintain the canals and water conduits, to the sophisticated and officious bureaucracy that made it all happen. And since there is no despotism so perfect as a hydraulic empire, “yellow” is absolute monarchy, centralization, and militarism. But “yellow” is also the military virtues — plain-spokenness, honesty, physical courage, stubbornness, and directness — the traditional stereotypes of the Chinese Northerner.

Far away, across the wide blue expanse of the Yangtze, lay the wild and untamed South. A land of rugged mountains and dense rainforest, both of them inhabited by tribes that the waves of migrating Chinese settlers viewed as both physically and spiritually corrosive. So those intrepid colonists built their cities by the water — clinging to the river systems and to the thousands of bays and inlets that crinkle the Southern Chinese coast into a fractal puzzle of land and sea. And thus they became “blue”.

“Blue” are the blue waters of the ocean and the doorways to non-Chinese societies, blue also is the culture of entrepreneurship, industry, trade, and cunning that spread from those rocky harbors first across Asia and then across the world. The Chinese diaspora that runs the economies of Southeast Asia and populates the Chinatowns in the West is predominately made up of “blue” peoples — the Cantonese, the Hakka, the Teochew, the Hokkien. “Blue” is independent initiative and innovation, because beyond the mountains the Emperor’s power is greatly attenuated. But “blue” is also corruption of every sort — the financial corruption of opportunistic merchants and unscrupulous magistrates, and the spiritual corruption of the jungle tribes and other non-Chinese influences. “Blue” is pirates and freebooters who made their lairs amidst the countless straits and islands and seaside caves. “Blue” is also unfettered sensuality — opium came to China via the great blue door, and more than one Qing emperor took a grand tour of the South for the purpose of sampling its brothels (considered to be of vastly higher quality).2

If you know nothing else about the geography of China, know that this is the primary distinction: North and South, yellow and blue.3 But this neglected period, the “time of division” after the collapse of the Jin, is when that distinction really started. Settlement of the South began under the Han Dynasty in the first couple centuries AD, but it was still very much a sparsely-populated frontier. What changed in the Middle Ages was that after the collapse of central authority and the invasion of the North by nomadic barbarians, a vast swathe of the intelligentsia, literati, and military aristocracy of the North fled across the Yangtze and set up a capital-in-exile. For the first time the South became really “Chinese”, but the society that emerged was a hybrid one that retained a Southern inflection.

It wasn’t just courtiers and generals and poets who fled to the South: millions and millions of ordinary peasants did too, which finally displaced the jungle tribes, and also altered the balance of power between North and South. For the first time in Chinese history, the South had more population, more wealth, and an arguably better claim to dynastic legitimacy. So when the North emerged from its period of anarchy and foreign domination and looked to reassert its traditional supremacy, the South said: “no”. The Southern dynasties, chief among them the Chen Dynasty,4 were able to maintain an uneasy military stalemate for almost two hundred years, thanks to the formidable natural barrier of the Yangtze River, and to the fact that Southerners were better versed in naval warfare and thus able to prevent any amphibious operations on the part of the North.

This only ended when the founder of the Sui Dynasty learned to fight like a Southerner, and assembled a massive naval force in the Sichuan basin, then floated it down the Yangtze gorges destroying everything in his path. The backbone of this force were massive ships which “had five decks, were capable of accommodating 800 men, and were outfitted with six 50-foot-long, spike-bearing booms that could be dropped from the vertical to damage enemy vessels or pin them in positions where they would be raked by close-range missile fire.” After breaking Southern control of the great river, the Sui founder assembled an invasion force of over half a million men and crushed the Southern armies, burned their capital city to the ground, and forcibly returned the entire aristocracy to the North.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900 by David A. Graff”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-06-05.

1. The Chinese Middle Ages and the European Middle Ages aren’t actually contemporaneous — “Medieval China” generally denotes a period just before and after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

2. “Blue” China is also the origin of a different sort of disordered sensuality — the culinary sort. Almost from the dawn of Chinese history, Northerners have been horrified by the gusto with which Southerners will eat anything. Scorpions, animal brains and eyeballs, you name it, Southerners are constantly upping the ante with each other. Northerners have also generally been horrified by the sadism that attends some Southern culinary traditions, with many animals being eaten alive, or partially alive, or after prolonged and deliberate torture. One usually unstated Northern view is that a lot of these customs were picked up from the jungle tribes that lurk in the Chinese imaginarium like the decadent ancestor in an H.P. Lovecraft story.

3. Confusingly, in the context of modern Hong Kong politics, “yellow” and “blue” represent the pro-sovereignty and pro-China factions respectively. This split is almost totally orthogonal to the one I’m talking about in this book review, and to the extent they aren’t orthogonal, the sign is flipped.

4. “Chen” is the most quintessentially Southern surname, but I’ve never been able to figure out whether that came before or after it was the name of the most famous Southern dynasty.

August 17, 2024

Caesar Marches on Rome – Historia Civilis Reaction

Vlogging Through History

Published Apr 23, 2024See the original here –

• Caesar Marches on Rome (49 B.C.E.)

See “Caesar Crosses the Rubicon” here –

• Caesar Crosses the Rubicon – Historia…#history #reaction

August 4, 2024

Caesar Crosses the Rubicon – Historia Civilis Reaction

Vlogging Through History

Published Apr 22, 2024See the original here – Caesar Crosses the Rubicon (52 to 49 …

#history #reaction

July 11, 2024

QotD: Armchair generals

Why, it appears that we appointed all of our worst generals to command the armies and we appointed all of our best generals to edit the newspapers. I mean, I found by reading a newspaper that these editor generals saw all of the defects plainly from the start but didn’t tell me until it was too late. I’m willing to yield my place to these best generals and I’ll do my best for the cause by editing a newspaper.

Robert E. Lee, quoted at American Digest, 2005-08.

July 10, 2024

Two World Wars: Finnish C96 “Ukko-Mauser”

Forgotten Weapons

Published Mar 27, 2024A decent number of C96 Mauser pistols were present in Finland’s civil war, many of them coming into the country with the Finnish Jaegers, and others from a variety of sources, commercial and Russian. They were used by both the Reds and the Whites, and in both 9x19mm and 7.63x25mm. After the end of the civil war, when the military was standardizing, the C96s were handed over to the Civil Guard, where they generally remained until recalled to army inventories in 1939. They once again saw service in the Winter War and Continuation War, and went into military stores afterwards until eventually being surplussed as obsolete.

One of the interesting aspects of Finnish C96s is that many of them come from the so-called “Scandinavian Contract” batch (for which no contract has actually turned up). These appear to be guns made in 7.63mm that were numbered as part of the early production in the Prussian “Red 9” series, probably for delivery to specific German units or partner forces during World War One.

(more…)

July 4, 2024

QotD: “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”

Memorial Day in America – or, if you’re a real old-timer, Decoration Day, a day for decorating the graves of the Civil War dead. The songs many of those soldiers marched to are still known today – “The Yellow Rose Of Texas”, “When Johnny Comes Marching Home”, “Dixie”. But this one belongs in a category all its own:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored…In 1861, the United States had nothing that was recognized as a national anthem, and, given that they were now at war, it was thought they ought to find one – a song “that would inspire Americans to patriotism and military ardor”. A 13-member committee was appointed and on May 17th they invited submissions of appropriate anthems, the eventual winner to receive $500, or medal of equal value. By the end of July, they had a thousand submissions, including some from Europe, but nothing with what they felt was real feeling. It’s hard to write a patriotic song to order.

At the time, Dr Samuel Howe was working with the Sanitary Commission of the Department of War, and one fall day he and Mrs Howe were taken to a camp a few miles from Washington for a review of General McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. That day, for the first time in her life, Julia Ward Howe heard soldiers singing:

John Brown’s body lies a-mould’ring in the grave

John Brown’s body lies a-mould’ring in the grave…Ah, yes. The famous song about the famous abolitionist hanged in 1859 in Charlestown, Virginia before a crowd including Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and John Wilkes Booth.

Well, no, not exactly. “By a strange quirk of history,” wrote Irwin Silber, the great musicologist of Civil War folk songs, “‘John Brown’s Body’ was not composed originally about the fiery Abolitionist at all. The namesake for the song, it turns out, was Sergeant John Brown, a Scotsman, a member of the Second Battalion, Boston Light Infantry Volunteer Militia.” This group enlisted with the Twelfth Massachusetts Regiment and formed a glee club at Fort Warren in Boston. Brown was second tenor, and the subject of a lot of good-natured joshing, including a song about him mould’ring in his grave, which at that time had just one verse, plus chorus:

Glory, glory, hallelujah

Glory, glory, hallelujah…They called it “The John Brown Song”. On July 18th 1861, at a regimental march past the Old State House in Boston, the boys sang the song and the crowd assumed, reasonably enough, that it was inspired by the life of John Brown the Kansas abolitionist, not John Brown the Scots tenor. Over the years in the “SteynOnline Song of the Week”, we’ve discussed lyrics featuring real people. But, as far as I know, this is the only song about a real person in which posterity has mistaken it for a song about a completely different person: “John Brown’s Body” is about some other fellow’s body, not John Brown the somebody but John Brown the comparative nobody. Later on, various other verses were written about the famous John Brown and the original John Brown found his comrades’ musical tribute to him gradually annexed by the other guy.

Mark Steyn, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”, Steyn Online, 2019-05-26.

June 24, 2024

History Summarized: Augustus Versus Antony

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published Apr 6, 2018Now that Caesar’s assassins are out of the picture, which would-be dictator will defeat the other to become the sole-ruler of Rome? In today’s episode of “How Long Before There’s Another Civil War?”: Not a lot … honestly not a very long time … BUT THEN WE GET THE ROMAN EMPIRE WOOOOOOOOO~~~

June 21, 2024

June 16, 2024

April 1, 2024

The most likely outcome of a 2nd US Civil War isn’t two successor states, but a modern version of the Holy Roman Empire

Kulak, at the start of a very long post on historical eras of centralization and decentralization, touches on the most likely outcome of a second US civil war, and it’s not a rump USA and a neo CSA:

Every time the subject of a possible US civil war or national divorce comes up I hear the same micron deep takes. America couldn’t break up because the division isn’t by state, its Urban Vs. Rural. Or that Urban vs. Rural isn’t the divide, even then people of different politics are mixed up together. Or that for every clear red or blue state there’s a purple state. None of which is in any way relevant to anything until you recognize the naïve mental model many of these people are working on …

These takes betray a belief that a second civil war would be some kind of conflict between coherent independent states who’ve started identifying with/against the idea of union such as happened in the 1860s … or that somehow there’d be a series of tidy Quebec style referendums resulting in a clean division such as exists in so many meme maps:

The truth is any post-breakup map of America would not resemble an electoral map following state lines, nor even a redrawing of state boundaries, such that the fantastical greater Idaho or Free State of Jefferson might exist as part of a wider Confederation of Constitutional Republics, or a Breakaway Philadelphia city-State join a Union of Progressive Democracies …

No. It’d be nothing so comprehensible or easily mapped to modern politics.

A post breakup America would probably look closer to this:

If you’re a sane person and your immediate reaction is: WHAT THE HELL AM I LOOKING AT!?

… Well that’s kinda the point.

(I really do apologize for all I’m going to have to digress)

For our purposes we can broadly divide history into 2 types of period … Periods of Centralizing trends, and periods of Decentralizing trends.