Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 5 Aug 2022Curb your Crusading – the artwork, literature, and scholarship are far more interesting.

SOURCES & Further Reading: China: A History by John Keay, Byzantium & Sicily & Venice by John Julius Norwich, Great Courses Lecture series Foundations of Western Civilization by Thomas F. X. Noble lectures 27 through 38: “The Emergence of the Catholic Church”, “Christian Culture in Late Antiquity”, “Muhammad and Islam”, “The Birth of Byzantium”, “Barbarian Kingdoms in the West”, “The World of Charlemagne”, “The Carolingian Renaissance”, “The Expansion of Europe”, “The Chivalrous Society”, “Medieval Political Traditions I”, “Medieval Political Traditions II”, and “Scholastic Culture”.

(more…)

December 10, 2022

The “Dark” Ages were fine, actually — History Hijinks

QotD: The Western Roman Empire – “decline and fall” or “change and continuity”?

So who are our [academic] combatants? To understand this, we have to lay out a bit of the “history of the history” – what is called historiography in technical parlance. Here I am also going to note the rather artificial but importance field distinction here between ancient (Mediterranean) history and medieval European history. As we’ll see, viewing this as the end of the Roman period gives quite a different impression than viewing it as the beginning of a new European Middle Ages. The two fields “connect” in Late Antiquity (the term for this transitional period, broadly the 4th to 8th centuries), but most programs and publications are either ancient or medieval and where scholars hail from can lead to different (not bad, different) perspectives.

With that out of the way, the old view, that of Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) and indeed largely the view of the sources themselves, was that the disintegration of the western half of the Roman polity was an unmitigated catastrophe, a view that held largely unchallenged into the last century; Gibbon’s great work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1789) gives this school its name, “decline and fall“. While I am going at points to gesture to Gibbon’s thinking, we’re not going to debate him; he is the “old man” of our title. Gibbon himself largely exists only in historiographical footnotes and intellectual histories; he is not at this point seriously defended nor seriously attacked but discussed as the venerable, but now out of date, origin point for all of this bickering.

The real break with that view came with the work of Peter Brown, initially in his The World of Late Antiquity (1971) and more or less canonically in The Rise of Western Christendom (1st ed. 1996; 2nd ed. 2003, 3rd ed. 2013). The normal way to refer to the Peter Brown school of thought is “change and continuity” (in contrast to the traditional “decline and fall”), though I rather like James O’Donnell’s description of it as the Reformation in late antique studies.

Among medievalists this reformed view, which focuses on continuity of culture and institutions from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages, remains essentially the orthodoxy, to the point that, for instance, the very recent (and quite excellent) The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe (2021) can present this vision as an uncomplicated fact, describing the “so-called Fall of Rome” and noting that “there was never a moment in the next thousand years in which at least one European or Mediterranean ruler didn’t claim political legitimacy through a credible connection to the empire of the Romans” and that “the idea that Rome ‘fell’ on the other hand, relies upon a conception of homogeneity – of historical stasis … things changed. But things always change” (3-4, 12-3). As we’ll see, I don’t entirely disagree with those statements, but they are absolute to a degree that suggests there is no real challenge to the position. There have been a few cracks in this orthodoxy among medievalists, particularly the work of Robin Flemming (a revision, not a clear break, to be sure), to which we’ll return, but the cracks have been relatively few.

While some ancient historians also bought into this view, purchase there has always been uneven and seems, to me at least, now to be waning further. Instead, a process of what James O’Donnell describes as a “counter-reformation” (which he stoutly resists with his own The Ruin of the Roman Empire; O’Donnell is a declared reformer) is well underway, a response to the “change and continuity” narrative which seeks to update and defend the notion that there really was a fall of Rome and that it really was quite bad actually. This is not, I should note, an effort to revive Gibbon per se; it does not typically accept his understanding of the cause of this decline (and often characterizes exactly what is declining differently). Nevertheless, this position too is sometimes termed the “decline and fall” school. My own sense of the field is that while nearly all ancient historians will feel the need to concede at least some validity to the reformed “change and continuity” vision, that the counter-reformation school is the majority view among ancient historians at this point (in a way that is particularly evident in overview treatments like textbooks or the Cambridge Ancient History (second edition)). We’ll meet many of the core works of this revised “decline and fall” school as we go.

As O’Donnell noted in a 2005 review for the BMCR, the reformed school tends to be strongest in the study of the imperial east rather than the west (something that will make a lot of sense in a moment), and in religious and cultural history; the counter-reformation school is stronger in the west than the east and in military and political history, though as we’ll see, to that list must at this point now be added archaeology along with demographic and economic history, at which point the weight of fields tends to get more than a little lopsided.

Those are our two knights – the “change and continuity” knight and the “decline and fall” knight (and our old man Gibbon, long out of his dueling days). To this we must add the nitwit: a popular vision, held by functionally no modern scholars, which represents the Middle Ages in their entirety as a retreat from a position of progress during the Roman period which was only regained during the “Renaissance” (generally represented as a distinct period from the Middle Ages) which then proceeded into the upward trajectory of the early modern period. Intellectually, this vision traces back to what Renaissance thinkers thought about themselves and their own disdain for “medieval” scholastic thinking (that is, to be clear, the thinking of their older teachers), a late Medieval version of “this ain’t your daddy’s rock and roll!”

But almost every intellectual movement represents itself as a radical break with the past (including, amusingly, many of the scholastics! Let me tell you about Peter Abelard sometime); as historians we do not generally accept such claims uncritically at face value. For a long time, well into the 19th century, the Renaissance’s cultural cachet in Europe (and the cachet of the classical period where it drew its inspiration) shielded that Renaissance claim from critique; that patina now having worn thin, most scholars now reject it, positioning the Renaissance as a continuation (with variations on the theme) of the Middle Ages, a smooth transition rather than a hard break. At the same time, knowledge of developments within the Middle Ages have made the image of one unbroken “Dark Age” untenable and made clear that the “upswing” of the early modern period was already well underway in the later Middle Ages and in turn had its roots stretching even deeper into the period. It is also worth noting here, that the term “Dark Age” has to do with the survival of evidence, not living conditions: the age was not dark because it was grim, it was dark because we cannot see it as clearly.

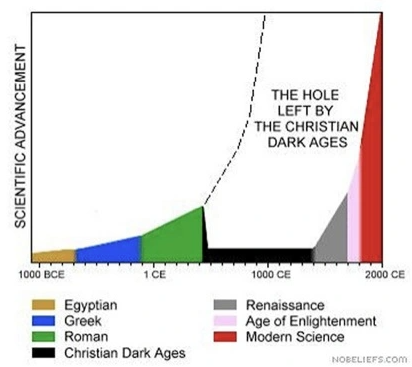

The popular version of this idea continues, however, to have a lot of sway in the popular conception of the Middle Ages, encouraged by popular culture that mistakes the excesses of the early modern period for “medieval” superstition and exaggerates the poverty of the medieval period (itself essentialized to its worst elements despite being approximately a millennia long), all summed up in this graph:

We are mostly going to just dunk relentlessly on this graph and yet we will not cover even half of the necessary dunking this graph demands. We may begin by noting that in its last century, the Roman Empire was Christian, a point apparently missed here.

While that sort of vision is not seriously debated by scholars, it needs to be addressed here too, in part because I suspect a lot of the energy behind the “change and continuity” position is in fact to counter some of the worst excesses of this thesis, which for simplicity, we’ll just refer to as “The Dung Ages” argument, but also because assessing how bad the fall of the Roman Empire in the West was demands that we consider how long-lasting any negative ramifications were.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Rome: Decline and Fall? Part I: Words”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-01-14.

December 9, 2022

Canada’s “historic” shift toward the Indo-Pacific is … more marketing than strategy

In The Line, retired Canadian Lieutenant General Mike Day distills down all the airy phrases to see just what the Canadian government is actually going to do in the Indo-Pacific as opposed to merely talking about it:

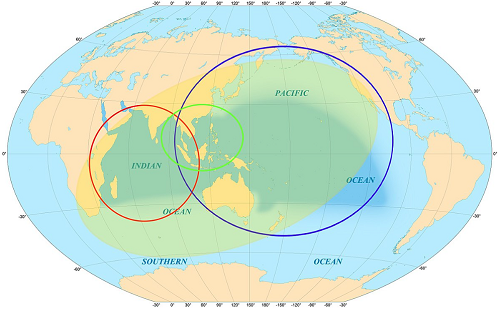

“Red circle/oval roughly depicts the Indian Ocean region. Blue circle/oval covers the Pacific region. Green oval covers ASEAN. Yellow overlay covers the Indo Pacific.”

Map annotation by Eric Gaba via Wikimedia Commons.

A formal public-policy statement from the Government of Canada is a rare thing. It is even rarer when it is not just a speech but a published written document. The rarest of these is undoubtedly when such a document focuses on foreign policy. When Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly recently pitched her “once-in-a-generation shift” toward the Indo-Pacific, much was made of why Canada was doing it and what it would achieve. No fewer than four cabinet ministers took part in the announcement. Canada will, they announced, step up naval patrols of the region, continue to expand trade with China while also tightening our protections of intellectual property and ownership rules for strategic industries, and use “Team Canada” trade missions to boost commercial links with other growing regional economic powers, including India. We seek also to expand our intelligence and cybersecurity links with allies and partners in the region.

Now that the dust on the rhetoric has settled, closer examination reveals that this might simply be an exercise of branding separate activities into a marketing-friendly bundle, as opposed to a coherent plan focused on achieving specific outcomes.

In examining the document two approaches are equally useful in assessing value: whether the content has some substance and whether the policy framework is sufficiently robust to hang various activities and plans on its body.

Three hints are provided as to why the new plan might not be the cornerstone of Canada’s foreign policy that it portends to be. Firstly, operating in the “National Interest”, a phrase used six separate times over the 26 pages, is given neither form nor function and lacks any definition. It is reminiscent of the Cheshire Cat talking to Alice asking her “where do you want to get to”. When Alice replies that “I don’t much care …” the Cheshire Cat wisely suggests that “Then it doesn’t matter which way you go.” With no definition of national interests pretty much anything can be hand waved as to being necessary and required, or not, for its achievement.

This leads in turn to the second hint that the plan might be more posturing than substance. Lacking the single aimpoint of operating in the national interest, the “objectives” supposedly fill that gap by providing a set of specific achievements which in combination would be a sufficiently clear aimpoint. But normally objectives can, and should, be thought of as something specific and measurable, allowing plans to be developed to achieve them. “Save 100 dollars this month” or perhaps, in more relevant terms, “Increase our trade in the Indo-Pacific region by 100 per cent over the five years of this policy enactment.” Plans can then be developed to achieve those objectives. But reviewing those objectives reveals that they are themselves actions, not end-states. It appears that the policy is based on “doing, not achieving”. I am reminded of my sons many years ago. When asked if their rooms were clean, they would reply, “I’m cleaning it.” The process was enduring but we most certainly disagreed on the value of the activity as opposed to achieving a measurable result. Under this construct the government can claim that as long as Canada is doing stuff the policy should be considered a success.

V-1: Hitler’s Deluded Revenge Plan – War Against Humanity 090

World War Two

Published 8 Dec 2022Japanese planes bomb Calcutta when it is still being crushed by the weight of the Bengali famine. Adolf Hitler and Albert Speer are obsessively trying to increase war production so Germany can begin launching its vengeance weapon against Britain. The wars of resistance continue across the Balkans with continued brutality and a new resistance force emerges in Italy.

(more…)

Caesar versus Cato

In The Critic, Daisy Dunn reviews Uncommon Wrath: How Caesar and Cato destroyed the Roman Republic by Josiah Osgood:

If there was one thing the Romans did well — aside from sanitation, irrigation and concrete — it was polemic. Cicero composed fourteen fiery Philippics against Mark Antony in the 40s BC, and Catullus jibed at Julius Caesar so profusely in his poems that he had to issue an apology. Less famous, but equally explosive, was Caesar’s own collection of vitriol. The Anticato survives today only in fragments, but according to an ancient satirist, it was originally so long that it took up two scrolls and almost outweighed the penis of Publius Clodius Pulcher, apparently among the best-endowed politicians in Rome.

Caesar wrote it shortly before he became dictator, with the intention of denigrating the memory of Marcus Porcius Cato, “Cato the Younger”. For years the two men had been locked in furious rivalry. Caesar blasted Cato as cold and miserly. Cato despaired at Caesar’s profligacy and tireless womanising. If Caesar was louche in his barely-belted toga and exotic unguents, Cato was positively austere — a prime hair-shirt candidate — with his bare feet, rustic diet, extreme exercise and strict sexual mores; it was most unusual for a Roman to make his wife the first woman he slept with.

Few would argue with Josiah Osgood, Professor of Classics at Georgetown, when he describes Caesar and Cato as opposites. Even Donald Trump and Joe Biden have more in common than they did. Caesar was the nephew of the wife of Gaius Marius, the populist enemy of Sulla, who as dictator had thousands of Italians proscribed and killed in his bid to restore the authority of the Senate. Cato could count Sulla as an old family friend. Caesar belonged to a well-established Roman family and claimed descent from Venus via her son Aeneas. Cato’s family was Sabine, and his most famous ancestor was a mere mortal in the shape of the plebeian writer and highly conservative statesman Cato the Elder.

The differences between Caesar’s and Cato’s personalities mattered because they reflected the differences in their visions for Rome. Osgood sums these up as “an empire wielding its power for the people” (Caesar) versus “a Senate protecting the people from the all-powerful empire builders” (Cato). It is little wonder they came to blows.

Osgood takes the tense relationship between Cato and Caesar as the central focus of his book. He argues that their feud has been overlooked as a contributing factor to the civil war that erupted in 49 BC and brought the Roman Republic crashing to the ground. Blame for this war has more usually been placed on the collapse of the First Triumvirate — an illegal alliance for power forged between Julius Caesar, Pompey the Great and Marcus Licinius Crassus in 60 BC — and the breakdown in relations between Caesar and Pompey in particular. But all wars have long-term and short-term causes. For Osgood, the dispute between Caesar and Cato was significant in at least the medium term.

Rod Bayonet Springfield 1903 (w/ Royalties and Heat Treat)

Forgotten Weapons

Published 20 Nov 2016(Note: I misspoke regarding Roosevelt’s letter; he was President at the time and writing to the Secretary of War)

The US military adopted the Model 1903 Springfield rifle in 1903, replacing the short-lived Krag-Jorgenson rifle. However, the 1903 would undergo some pretty substantial changes in 1905 and 1906 before becoming the rifle we recognize today. The piece in today’s video is an original Springfield produced in 1904, before any of these changes took place.

The most notable difference is the use of the rod bayonet. When the 1903 was in development, the Ordnance Department opined that the bayonet was largely obsolete, and that it was unnecessary to encumber soldiers with a long blade hanging from the belt. Instead, the new rifle would have a retractable spike bayonet that could double as cleaning rod and would be stored in the rifle stock, unobtrusive to the soldier. This ended in 1905 with a critical letter from Theodore Roosevelt (who was Secretary of War at the time). As the rod bayonet was replaced with a traditional blade bayonet, the cartridge would also be improved to a new style spitzer projectile at higher velocity, and the rifles’ stocks, hand guards, and sights were redesigned.

In this video I also discuss two often misunderstood elements of the Springfield’s history: heat treating and patent royalties. Are low serial number 1903 Springfields safe to shoot, and why or why not? And did the US government actually pay royalties to Germany for copying Mauser elements in the 1903?

(more…)

QotD: Computer models of “the future”

The problem with all “models of the world”, as the video puts it, is that they ignore two vitally important factors. First, models can only go so deep in terms of the scale of analysis to attempt. You can always add layers — and it is never clear when a layer that is completely unseen at one scale becomes vitally important at another. Predicting higher-order effects from lower scales is often impossible, and it is rarely clear when one can be discarded for another.

Second, the video ignores the fact that human behavior changes in response to circumstance, sometimes in radically unpredictable ways. I might predict that we will hit peak oil (or be extremely wealthy) if I extrapolate various trends. However, as oil becomes scarce, people discover new ways to obtain it or do without it. As people become wealthier, they become less interested in the pursuit of wealth and therefore become poorer. Both of those scenarios, however, assume that humanity will adopt a moral and optimistic stance. If humans become decadent and pessimistic, they might just start wars and end up feeding off the scraps.

So, interestingly, what the future looks like might be as much a function of the music we listen to, the books we read, and the movies we watch when we are young as of the resources that are available.

Note that the solution they propose to our problems is internationalization. The problem with internationalizing everything is that people have no one to appeal to. We are governed by a number of international laws, but when was the last time you voted in an international election? How do you effect change when international policies are not working out correctly? Who do you appeal to?

The importance of nationalism is that there are well-known and generally-accepted procedures for addressing grievances with the ruling class. These international clubs are generally impervious to the appeals (and common sense) of ordinary people and tend to promote virtue-signaling among the wealthy class over actual virtue or solutions to problems.

Jonathan Bartlett, quoted in “1973 Computer Program: The World Will End In 2040”, Mind Matters News, 2019-05-31.

December 8, 2022

Is the Luftwaffe Defeated in 1943? – WW2 Documentary Special

World War Two

Published 7 Dec 2022Outnumbered and outproduced, the once mighty Luftwaffe is battling to hold its own across three fronts. Every month brings new pain for the force. But the Luftwaffe still has a few tricks up its sleeves and can make the Allies bleed heavily. If only Hitler and the Nazi leadership weren’t sabotaging its chances …

(more…)

Meta (the artist formerly known as Facebook) moves to clamp down on political discussions in the workplace

Tom Knighton on an uncharacteristic corporate move by the artist formerly known as Facebook:

It seems there are certain words employees aren’t really supposed to bring up in the workplace.

Meta (formerly Facebook) has reportedly told its employees not to discuss sensitive issues like abortion, gun control, pending legislation and vaccine efficacy at workplace.

According to a report in Fortune, citing a leaked internal memo, Meta has banned employees from discussing “very disruptive” topics, including abortion, gun rights, and vaccines as part of new “community engagement expectations”.

“As Mark mentioned recently, we need to make a number of cultural shifts to help us deliver against our priorities,” read the company memo.

“We’re doing this to ensure that internal discussions remain respectful, productive, and allow us to focus. This comes with the trade-off that we’ll no longer allow for every type of expression at work, but we think this is the right thing to do for the long-term health of our internal community,” it added.

Unfortunately for Meta, employees hammered them on the fact that they could talk about Black Lives Matter, immigration, and trans rights.

Now, they’re not really wrong to call out the hypocrisy, but this sounds like just a first move, and it’s a step in the right direction.

What would have been a better move is simply prohibiting discussing politics with your coworkers unless it directly pertains to your job. For example, if you are responsible for content moderation and a new bill will impact how you conduct that moderation, that’s one thing.

But topics ranging from Black Lives Matter to gun control are all contentious issues, and while Meta might have allowed that discussion in the past, they probably won’t indefinitely.

This is interesting to me, in part because we’ve seen the woke in the technology sector essentially bully employers into following along with the left’s agenda. Yet when they tried that with Netflix, the streaming giant basically told them to suck it up.

That was in May, but it may have triggered companies to realize that they didn’t have to play the woke game.

Last week, in the weekly wrap-up, I included this story about how Disney’s returning CEO Bob Iger is trying to have the company step back from the political ledge. Iger is far from a conservative, mind you, but he’s come to realize that his personal political agenda isn’t going to sell.

Granted, he started them along that path, but he’s recognized it’s not a great road to go down.

Now, we have Meta that may be venturing on a similar path to Netflix, setting the stage for what’s appropriate and what isn’t.

Byzantine Honey Fritters

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 26 Jul 2022

(more…)

QotD: Politicians’ public displays of sorrow

… our own politicians are increasingly given to hyperbole over the emotional impact upon them of accidents or disasters. They think that extravagant displays of emotion are required of them, and perhaps they are right. Any leader who doesn’t rush immediately to the scene of a disaster and utter heartfelt platitudes is regarded as a monster of coldheartedness who will lose the next election. We have forgotten that empty vessels make the most noise and demand not so much our pound of flesh as our flow of tears and outpouring of cliché.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Tears of a Tyrant”, Taki’s Magazine, 2018-04-28.

December 7, 2022

The Marie Antoinette Diet

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 6 Dec 2022

(more…)

The media: they hate you, they really hate you

In a follow-up to yesterday’s post at Thank You Truckers!, Donna Laframboise provides more details on one of the individual cases highlighted by Douglas Murray in the Munk Debates last week:

Collectively, those examples demonstrate three things: Egregious journalistic bias. A frightening inability to empathize with the working class. And a bizarre eagerness to slander and dismiss fellow human beings.

Because the examples cited by Murray are vile, I didn’t amplify them. But those of you who watched the three-minute clip heard about them. On further reflection, therefore, I’m going to highlight one of them. Simply to make the point that Murray wasn’t exaggerating. When he used the words rancid and corrupt to describe our current media environment, he was wholly on target. Here’s a small portion of Murray’s remarks, including some third party profanity:

You had a Toronto Star columnist saying, quote (sorry for the language), it’s a homegrown hate farm that was then jet-fuelled by an American right-funded rat-fucking operation …

Yup, that was a real tweet from Bruce Arthur, who earns his living as a sports writer, currently for the Toronto Star. Below is his full reply to comments made by another Canadian journalist, Jeet Heer, who writes for The Nation, a far-left US publication:

I worked with both these gentlemen 20 years ago, in the earliest days of the National Post. It was a large newsroom. I didn’t get to know either of them.

The day after they catapulted these deluded, venomous tweets into the world, I arrived in Ottawa. I spent a week there, taking photos and actually talking to people. The Freedom Convoy protesters I met were supremely decent human beings. Since then, I’ve formally interviewed many of them. I’ve learned about their lives, their triumphs, their troubles, their sorrow.

My conclusion? If I were stranded on a desert island — or if a nuclear bomb detonated anywhere near me — I’d be sticking close to folks like these. People who know how to fix things, how to build things, and how to get things done. People sufficiently concerned about right and wrong to put themselves at risk. People of faith, many of them, who show us religion at its finest — a stable, calming force. A source of courage, strength, and big picture perspective.

Those who protested in Ottawa were human beings, not saints. That’s true of every large gathering. But overwhelmingly, they were decent, salt-of-the-earth people.

Even the members of the Canadian media still trying to be more even-handed in their coverage felt obligated to go looking for the red-hatted Trump supporters, the “hard men”, and the potential trouble-makers to the point that those relatively few people seemed disproportionally represented in the published articles. Of course, all of them spent a lot of time and effort desperately searching for more idiots like that paid government agent who’d briefly been able to get on-camera waving his Nazi flag …