The current meritocratic system began as an effort to open up a hereditary WASP elite to outsiders — and for a while, as immigrants, minorities, and women earned their way into America’s legacy campuses, writes Markovits, it looked like it was working more or less as intended. In the last few decades, however, the system has morphed into a do-or-die tournament for the prize of an Ivy League degree and a bonus-rich job at a swanky address. Instead of being democracies of talent, Harvard and Yale and their elite cronies are now quasi-exclusive clubs for the children of wealth. Money gives rich parents the means to groom their kids for these clubs as early as infancy with classes, books, and trips to museums meant to enhance kids’ development. They move to wealthy neighborhoods, where schools offer a vast array of (ahem) “enrichment” activities, including test prep and college-essay tutoring. Alternatively, they put their kids through 12 years of $40,000-a-year-plus private schools, whose administrators just happen to be chummy with Princeton admission officers.

Their efforts pay off for their progeny, but in the harsh competition that is the contemporary economy, they leave everyone else in the dust. Nourished in the hothouse of elite homes and communities, rich children have pulled away from their middle-class counterparts when it comes to academic performance, outscoring them on the SAT by twice as much as middle-class kids outscore poor students. The most elite colleges enroll more students from households in the top 1 percent than from the entire bottom half of the income scale. Those students are first in the pipeline to elite jobs. Top banks go only to the Ivy League, MIT, and Stanford for their recruiting. Top Five law schools are the training grounds for partners at the poshest firms. Meantime, middle-class kids are not only a rare sight on elite campuses; they’re also far less likely to get any college degree. Poor kids do worse still.

The result, says Markovits, is precisely the sort of dynastic elite that the putatively unbiased SAT was supposed to put out of business. To the dismay of his critics on the left, Markovits is not entirely unsympathetic to the winners of the tournament. The rich used to be indolent, he reminds us. The whole point of wealth was to be freed from toil, while peasants sweated in fields and manor kitchens to serve their betters and eke out a living for their undernourished families. These days, by contrast, the rich work 16-hour days and weekends under immense competitive pressure to close the deal, make partner, and take a conference call with Japanese businessmen. “No prior elite has ever been as capable or as industrious as the meritocratic elite that such training produces. None comes close,” Markovits asserts. Yes, a few actresses and real estate barons try to bribe and cheat their children into the palaces of learning, but most Ivy Leaguers have used their privileged upbringing to make their way into these bastions according to the rules of achievement. Given the expensive grooming required to make it to the top campuses, he implies, a squeaky-clean meritocracy would still favor the rich.

Kay S. Hymowitz, “Meritocrats versus Meritocracy”, City Journal, 2019-10-11.

January 25, 2024

QotD: How Meritocracy morphed into “Meritocracy”

January 5, 2024

The value of college degrees

Ted Gioia isn’t a college dropout, but he’s seen enough to realize that given how his career has gone, he might well have saved himself a lot of time and money by not going to university in the first place:

I spent almost a decade and huge sums of money — much of it borrowed in the form of student loans — to earn multiple degrees from elite institutions.

But I don’t have a degree in music — the field that became my vocation. And I never took a single course or lesson in jazz (my specialty) during my entire life.

I wasn’t a dropout, not even close. But it’s sobering to consider my life in retrospect, and see how much it relied on what I taught myself outside of the classroom. So I now have a very different view of college than I did back when I was a student.

My more mature view is as follows:

(1) A college degree is more about signaling your worth than about learning.

This is hardly a brilliant insight — many are now saying this. But when you’ve lived it yourself, it changes your perspective on everything.[…]

(2) College provides inspiring role models — but they also exist in other settings.

I was blessed with a small number of teachers and mentors who taught me by example — and most of this happened at high school and college. There is no substitute for seeing greatness in the flesh at close hand.But this can happen outside of college — my wife, for example, had those experiences working as a dancer and choreographer in New York. She learned more from her mentor Erick Hawkins than from any college professor.

[…]

(3) Dropping out is a real option with genuine upside, but it’s not for everybody.

Let me put it as simply as possible: Many successes are dropouts, but few dropouts are successes.I would advise against abandoning your education for simple reasons of avoidance — because classes are a hassle, tests are a bummer, etc. But if you have a genuine vision of your life and the skills to achieve it, college is purely optional. And perhaps even hazardous.

(4) As the college experience becomes more expensive and close-minded, the appeal of alternatives increases exponentially.

At what price does college become a bad deal? I don’t have an answer to that, but we must be close to a tipping point.If I tried to replicate my formal education today, it would cost ten times as much. I would have student loans as large as the national debt of a mid-sized country. That’s just ridiculous.

But this kind of irrational endpoint results when a bloated bureaucracy increases tuition at more than the inflation rate every year — and continues doing so for a half century. The people running our major universities think they can get away with this because customers want impressive diplomas, and can be squeezed to an infinite degree.

But infinity doesn’t actually exist in human affairs. And unsustainable trends eventually prove just that, namely that they are unsustainable.

(5) The smartest people will increasingly bypass the system.

I can’t emphasize this enough. My advice to young people today is very different from what I would have said just 5 years ago.I now tell them to find ways to work outside of bureaucratic legacy institutions.

[…]

(6) Dropouts really do change society.

As someone who invested so much time and money in big-ticket credentials, that’s painful to admit. But I’ve seen too much to ignore the facts. I now grasp that people who are genuine visionaries know at an early stage that they can teach themselves, think for themselves, and manage themselves. Those are more valuable skills than any degree.So maybe I didn’t drop out like my friend’s buddy at Harvard, back in the mid-1970s. But I wouldn’t laugh at the idea nowadays, the way I did back then. And if I had everything to do over again, I might drop out myself.

Qatar’s Aggies

In The Free Press, Eli Lake discusses the deal between Texas A&M and the Qatari government that gives the Qatar Foundation — run by the Qatari royal family — full ownership of any intellectual property developed at the Qatari campus of the university:

What does Qatar get for its investment in U.S. universities? The answer may surprise you. In addition to the prestige and the influence of affiliating one’s national philanthropy with elite schools, Qatar is also accumulating the kind of technical research that was once the prize of American universities.

Consider Texas A&M University, one of the best places in the country to study nuclear engineering. Last month, The Free Press obtained exclusive access to a copy of the latest contract between Texas A&M and the Qatar Foundation that shows all of the intellectual property developed at the university’s campus in Doha belongs to the Qatar Foundation, a national philanthropy owned by the country’s royal family.

“The Qatar Foundation shall own the entire right, title, and interest in all Technology and Intellectual Property developed at (Texas A&M University Qatar) or under the auspices of its Research Program, other than those developed by non-TAMUQ employees and without financial support from the Qatar Foundation or any of its affiliates,” says the contract, dated May 25, 2021.

This kind of arrangement is common for large research universities in America. But TAMUQ is not your ordinary university. It is entirely funded by the Qatar Foundation. Kelly Brown, a spokeswoman for Texas A&M, told me that Qatar “pays for all faculty and staff salaries” as well as the physical campus, labs and equipment, housing, transportation, and travel allowances for professors.

It’s no small matter. The intellectual property generated by Texas A&M University in Qatar, or TAMUQ, includes highly sensitive research in a variety of fields ranging from computer science to bioengineering. Last year, TAMUQ inked an agreement to develop projects with a subsidiary of Barzan Holdings, Qatar’s largest arms manufacturer.

Andre Conradie, the CEO of the joint venture between Barzan and Germany’s Rheinmetall, said at the time, “This partnership will encourage the development of technological and operational capabilities to enhance military protection.”

As one of the country’s premier schools in nuclear engineering, Texas A&M has access to two nuclear reactors in Texas not affiliated with the U.S. government. In December, the National Nuclear Security Administration renewed a contract for the university, along with the University of California and Battelle Memorial Institute, to manage the Los Alamos National Laboratory, which involves oversight of teams who design and maintain nuclear weapons for the U.S. government.

January 4, 2024

“Missing from Gay’s note was some important … context”

Oliver Wiseman and Bari Weiss consider the resignation-under-pressure of Harvard President Claudine Gay:

Why did Claudine Gay step down yesterday as president of Harvard? In a letter announcing the bombshell decision, Gay wrote that it was in “the best interests of Harvard for me to resign so that our community can navigate this moment of extraordinary challenge with a focus on the institution rather than any individual.”

She also blamed racism: “It has been distressing to have doubt cast on my commitments to confronting hate and to upholding scholarly rigor — two bedrock values that are fundamental to who I am — and frightening to be subjected to personal attacks and threats fueled by racial animus,” Gay wrote in her email Tuesday.

Missing from Gay’s note was some important … context.

In particular, there was no mention of the twin scandals that have plagued Gay and captured the attention of the country in recent weeks. The first: her handling of antisemitism and free expression on Harvard’s campus since October 7, including her appalling appearance before Congress in December.

The second: the ever-growing list of plagiarism allegations against Gay. On Monday night, the dogged journalists over at The Washington Free Beacon reported six more charges of plagiarism. That brought the number of allegations against Gay close to 50 and implicated half of her published works in the scandal. The next day, Gay was gone, making her the shortest-serving president in Harvard’s history: the Kevin McCarthy of higher ed.

Within minutes the crowing began. Major props went to Bill Ackman, the billionaire investor who has relentlessly criticized his alma mater since the attacks of October 7; to Chris Rufo, the Manhattan Institute senior fellow who was early on the story of plagiarism allegations against Gay; and to Free Beacon reporter Aaron Sibarium (more about him in a minute).

But does Gay’s resignation — and apparently she will remain on the faculty — actually change things?

Our sense — and recent events have only reinforced it — is that Claudine Gay is only the symptom of a deeper rot, both at Harvard and across higher education more generally.

One of the people who has been outspoken about that deeper crisis is Jeffrey Flier, who was the dean of Harvard Medical School from 2007 to 2016 and is a member of the Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard, a group founded by Harvard academics last year to fight the free speech crisis on their campus. (Harvard ranks dead last with a score of 0.00 in FIRE’s college free speech rankings.)

We spoke to Flier hours after Claudine Gay’s resignation. He said he sees the present crisis as a chance for the university to fix itself. “Her departure may have been necessary. But the university needs to do more than appoint a new president,” he explained.

“Before October 7, few people thought fixing problems at Harvard was a really urgent need. I am with a group that wanted real change, but relatively few people were listening. But now there is real opportunity for change,” explains Flier.

December 24, 2023

QotD: Dreaming of George Bailey’s world while living in Pottersville

George Bailey, the hero of It’s a Wonderful Life, missed the two events that made the ideal man of his time, place, and social class: going to college and serving (as an officer, of course) in the Second World War. Instead of doing those things, either of which would have sent him out into the world beyond the limits of Bedford Falls, he remained at home, taking care of his family, his business, and his community. In other words, the hero of America’s favorite exercise in Yuletide nostalgia epitomized a way of life that, in the season of the film’s cinematic debut (the summer of 1946), was already on its way to the dustbin of history.

This, the most enduring of the many works of Frank Capra, became the Atlantis myth of post-war America. That is, those who, over the course of the last half-century, saw It’s a Wonderful Life on television, knew well that the age of community and connection depicted on their screens had already passed into the realm of legend. Moreover, to add injury to insult, they also knew that, if they wished to enjoy the fruits of a middle-class existence, they would have to live in the manner of vagabonds.

In the movie, slum-lord Henry Potter tries, but fails, to turn the provincial paradise of Bedford Falls into a run-down haunt of spinsters, drunks, and floozies. In the real world, it was Franklin D. Roosevelt who put the kibosh on the original Main Street, USA. To be more precise, the principal achievements of America’s greatest tyrant, the Great Depression and the Second World War, undermined the financial, legal, and cultural foundations of the “wonderful life”. Thus, by the time this process had run its course, inflation had made a fool’s game of simple thrift, the replacement of law with regulation had hobbled private enterprise, and people who had left home for the sake of college, work, or military service found themselves lost in a sea of strangers.

In response to these changes, colleges and universities stepped up to the proverbial plate, happy to offer substitutes for the things that had been lost. They gave young people a chance to obtain certificates that would attest to both their suitability for service in the ranks of corporate minions and their social respectability. At the same time, these institutions gave older people a way to convert their value-losing cash into an asset that promised to pay dividends that would benefit their children (and, indeed, their grandchildren) for decades to come.

Thus arose the people I have come to call the MICE (Mobile, Individualistic, College Educated) people. Bereft of regional accents, productive property, and deep connections to friends and relations, they wandered the world, building networks, acquiring degrees, and padding resumés. However, after two generations of such peripatetic solipsism, the age of the MICE people is coming to an end.

Young men of parts, who realize that college has nothing to do with either liberal learning or vocational training, are simultaneously taking up skilled trades and stocking their MP3 players with learned podcasts. At the same time, young women of quality are beginning to think that the traditional troika of Kirche, Küche, und Kinder offers better odds of deep satisfaction than life as a hormone-hobbled, Starbucks swilling, girl boss.

So, if you know young people like the ones I’ve just described, do posterity a favor, and put them in contact with each other. After all, they deserve a life as wonderful as that of George and Mary Bailey.

Bruce Ivar Gudmundsson, “College, Class, and Christmas”, Extra Muros, 2023-08-06.

December 13, 2023

December 12, 2023

La trahison des intellectuels modernes

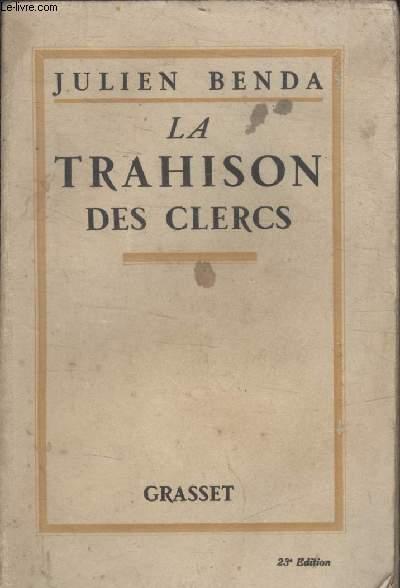

Niall Ferguson explains why the situation in Europe in the late 1920s persuaded Julien Benda to publish the famous La trahison des clercs … and how similar the situation in western academia is to a century ago:

In 1927 the French philosopher Julien Benda published La trahison des clercs — “The Treason of the Intellectuals” — which condemned the descent of European intellectuals into extreme nationalism and racism. By that point, although Benito Mussolini had been in power in Italy for five years, Adolf Hitler was still six years away from power in Germany and 13 years away from victory over France. But already Benda could see the pernicious role that many European academics were playing in politics.

Those who were meant to pursue the life of the mind, he wrote, had ushered in “the age of the intellectual organization of political hatreds”. And those hatreds were already moving from the realm of the ideas into the realm of violence — with results that would be catastrophic for all of Europe.

A century later, American academia has gone in the opposite political direction — leftward instead of rightward — but has ended up in much the same place. The question is whether we — unlike the Germans — can do something about it.

For nearly ten years, rather like Benda, I have marveled at the treason of my fellow intellectuals. I have also witnessed the willingness of trustees, donors, and alumni to tolerate the politicization of American universities by an illiberal coalition of “woke” progressives, adherents of “critical race theory”, and apologists for Islamist extremism.

Throughout that period, friends assured me that I was exaggerating. Who could possibly object to more diversity, equity, and inclusion on campus? In any case, weren’t American universities always left-leaning? Were my concerns perhaps just another sign that I was the kind of conservative who had no real future in the academy?

Such arguments fell apart after October 7, as the response of “radical” students and professors to the Hamas atrocities against Israel revealed the realities of contemporary campus life. That hostility to Israeli policy in Gaza regularly slides into antisemitism is now impossible to deny.

I cannot stop thinking of the son of a Jewish friend of mine, who is a graduate student at one of the Ivy League colleges. Just this week, he went to the desk assigned to him to find, carefully placed under his computer keyboard, a note with the words “ZIONIST KIKE!!!” in red and green letters.

Just as disturbing as such incidents — and there are too many to recount — has been the dismally confused responses of university leaders.

December 4, 2023

QotD: The “ivory gulag”

Looking at the cat ladies of both sexes and all 57 genders who ruined Trashcanistan, it seems obvious that they skipped sexual maturity – they jumped straight from “tween-ager” to “menopausal”. Even the young women in the “Social Justice” movement look – and, crucially, act – like they’re pushing fifty, while the young “men” are neotenous. Most of them are what bodybuilders call “skinny fat” – scrawny yet flabby, with no muscle tone – and the rest are morbidly obese. A crowd of college kids, again of both sexes and all however-many genders, looks like the mosh pit at the Lilith Fair. Without their exaggerated displays of secondary sex characteristics – ironic facial hair on the lads, pussy hats on the lassies – who could even tell them apart?

So, too, with their mentalities. I spent many years toiling in the groves of academe, so obviously my social life (such as it was) contained a lot of post-menopausal lesbians. No creature is more solipsistic than this. Whatever maternal instincts she once might’ve had, have curdled into general naggy truculence, and since they have all the money and free time in the world in which to indulge their narcissism, if they can’t find any actual wrongthink around they’ll simply invent some. Before the Deplorables were driven to organize themselves for gaudy, suicidal, IRA-style violence, post-Oranzhevvy Trashcanistan felt, I imagine, a lot like a college campus …

… which the few people with normal serum hormone levels who were stuck there often called “the ivory gulag”. Make of that what you will.

Severian, “Hormones, or Lack Thereof”, Founding Questions, 2021-01-20.

December 3, 2023

November 29, 2023

Alfred the Great

Ed West‘s new book is about the only English king to be known as “the Great”:

There are no portraits of King Alfred from his time period, so representations like this 1905 stained glass window in Bristol Cathedral are all we have to visually represent him.

Photo by Charles Eamer Kempe via Wikimedia Commons.

History was once the story of heroes, and there is no greater figure in England’s history than the man who saved, and helped create, the nation itself. As I’ve written before, Alfred the Great is more than just a historical figure to me. I have an almost Victorian reverence for his memory.

Alfred is the subject of my short book Saxons versus Vikings, which was published in the US in 2017 as the first part of a young adult history of medieval England. The UK edition is published today, available on Amazon or through the publishers. (use the code SV20 on the publisher’s site, valid until 30 November, which gives 20% off). It’s very much a beginner’s introduction, aimed at conveying the message that history is just one long black comedy.

The book charts the story of Alfred and his equally impressive grandson Athelstan, who went on to unify England in 927. In the centuries that followed Athelstan may have been considered the greater king, something we can sort of guess at by the fact that Ethelred the Unready named his first son Athelstan, and only his eighth Alfred, and royal naming patterns tend to reflect the prestige of previous monarchs.

Yet while Athelstan’s star faded in the medieval period, Alfred’s rose, and so by the fifteenth century the feeble-minded Henry VI was trying to have him made a saint. This didn’t happen, but Alfred is today the only English king to be styled “the Great”, and it was a word attached to him from quite an early stage. Even in the twelfth century the gossipy chronicler Matthew Paris is using the epithet, and says it’s in common use.

However, much of what is recorded of him only became known in Tudor times, partly by accident. Henry VIII’s break from Rome was to have a huge influence on our understanding of history, chiefly because so many of England’s records were stored in monasteries.

Before the development of universities, these had been the main intellectual centres in Christendom, indeed from where universities would grow. Now, along with relics, huge amounts of them would be lost, destroyed, sold … or preserved.

It was lucky that Matthew Parker, the sixteenth-century Archbishop of Canterbury with a keen interest in history, had a particularly keen interest in Alfred. It was Parker who published Asser’s Life of Alfred in 1574, having found the manuscript after the dissolution of the monasteries, a book that found itself in the Ashburnham collection amassed by Sir Robert Cotton in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

Sadly, the original Life was burned in a famous fire at Ashburnham House in Westminster on October 23, 1731. Boys from nearby Westminster School had gone into the blaze alongside the owner and his son to rescue manuscripts, but much was lost, among them the only surviving manuscript of the Life of Alfred, as well as that of Beowulf. In fact the majority of recorded Anglo-Saxon history had gone up in smoke in minutes.

A copy of Beowulf had also been made, although the poem only became widely known in the nineteenth century after being translated into modern English. The fire also destroyed the oldest copy of the Burghal Hidage, a unique document listing towns of Saxon England and provisions for defence made during the reign of Alfred’s son Edward the Elder. An eighth-century illuminated gospel book from Northumbria was also lost.

So it is lucky that Parker had had The Life of Alfred printed, even if he had made alterations in his copy that to historians are infuriating because they cannot be sure if they are authentic. He probably added the story about the cakes, for instance, although this had come from a different Anglo-Saxon source.

We also know that Archbishop Parker was a bit confused, or possibly just lying; he claimed Alfred had founded his old university, Oxford, which was clearly untrue, and he was probably trying to make his alma mater sound grander than Cambridge. Oxford graduates down the years have been known to do this on one or two occasions.

November 26, 2023

QotD: From Industrial Revolution labour surplus to modern era academic surplus

Back in Early Modern England, enclosure led to a massive over-supply of labor. The urge to explore and colonize was driven, to an unknowable but certainly large extent, by the effort to find something for all those excess people to DO. The fact that they’d take on the brutal terms of indenture in the New World tells you all you need to know about how bad that labor over-supply made life back home. The same with “industrial innovation”. The first Industrial Revolution never lacked for workers, and indeed, Marxism appealed back in its day because the so-called “Iron Law of Wages” seemed to apply — given that there were always more workers than jobs …

The great thing about industrial work, though, is that you don’t have to be particularly bright to do it. There’s always going to be a fraction of the population that fails the IQ test, no matter how low you set the bar, but in the early Industrial Revolution that bar was pretty low indeed. So much so, in fact, that pretty soon places like America were experiencing drastic labor shortages, and there’s your history of 19th century immigration. The problem, though, isn’t the low IQ guys. It’s the high-IQ guys whose high IQs don’t line up with remunerative skills.

My academic colleagues were a great example, which is why they were all Marxists. I make fun of their stupidity all the time, but the truth is, they’re most of them bright enough, IQ-wise. Not geniuses by any means, but let’s say 120 IQ on average. Alas, as we all know, 120-with-verbal-dexterity is a very different thing from 120-and-good-with-a-slide-rule. Academics are the former, and any society that wants to remain stable HAS to find something for those people to do. Trust me on this: You do not want to be the obviously smartest guy in the room when everyone else in the room is, say, a plumber. This is no knock on plumbers, who by and large are cool guys, but it IS a knock on the high-IQ guy’s ego. Yeah, maybe I can write you a mean sonnet, or a nifty essay on the problems of labor over-supply in 16th century England, but those guys build stuff. And they get paid.

Those guys — the non-STEM smart guys — used to go into academia, and that used to be enough. Alas, soon enough we had an oversupply of them, too, which is why academia soon became the academic-industrial complex. 90% of what goes on at a modern university is just make-work. It’s either bullshit nobody needs, like “education” majors, or it’s basically just degrees in “activism”. It’s like Say’s Law for retards — supply creates its own demand, in this case subsidized by a trillion-dollar student loan industry. Better, much better, that it should all be plowed under, and the fields salted.

Any society digging itself out of the rubble of the future should always remember: No overproduction of elites!

Severian, “The Academic-Industrial Complex”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-05-30.

November 22, 2023

QotD: American universities, “sportsball”, and wealthy alumni

It is, or at least used to be, a truth universally acknowledged, that the Athletic Department was the only bastion of sanity left in higher “education”. I love watching Marxists squirm, so the start of football season was always my favorite time back in my professin’ days. Every year, the doofus Marxoid faculty would write their annual complaint about sportsball — “not germane to the purpose of a university”; “takes away too many resources from academics”; “toxic masculinity” and so forth — and every year, the President and Board of Trustees would tell the eggheads to go pound sand.

NOT, I hasten to add, because the Prez and the Trustees (hereafter: The Administration) were some kind of normal folks. Oh God no — quite the opposite, in fact. No open conservative has been hired to any position in academia for the past thirty, forty years; to make it into the ranks of The Administration, you have to be #woker than #woke. Rather, it was because The Administration were among the few mortals privy to the college’s balance sheet. Seriously, those things are more closely guarded than our nuclear launch codes … but The Administration sees them, and draws the only possible conclusion: Without sportsball, the whole university system is toast.

But alas for the bottom line, Intersectionality is a jealous god, and xzhey will have none before xzhem. The Administration knows — they must know, they can’t not know — that all the stuff that makes big league college football go comes from “boosters”, i.e. rich idiots with way more money than sense, and their corporations. But since The Administration is full of even dumber Marxists than the faculty — yeah yeah, I know, I didn’t think it was possible either — they’ve apparently decided to assume, in true Leftist style, that since the money has always just kinda, you know, been there, it will continue to, you know, somehow, someway, continue to be there.

I mean, what are those rich oilmen from Texas gonna do, not watch football?

Severian, “Ludicrous Speed Update: The NCAA”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-04-14.

November 18, 2023

QotD: Teaching Marx’s Labour Theory of Value in university

You have to deal with Marx and Marxists in every nook and cranny of the ivory tower, of course, but when you teach anything in modern history you have to confront him head on. Since Marx was a shit-flinging nihilist pretending to be a philosopher while masquerading as an economist, economics is the easiest entry point to his thought. So I’d go at him head-on.

The Labor Theory of Value makes intuitive sense, especially to college kids, who consider themselves both idealists and socially sophisticated. So, I’d tell them, we all agree: Nike’s sneakers cost $2 to make, but sell for $200; therefore, the other $198 must be capitalist exploitation, right? In a socially-just world, sneakers would never cost more than $2, since that’s the amount of “socially useful” labor that went into making them.

To really get them thinking, at that point I’d offer to trade them my shoes, which were of course the butt-ugliest things I could find, bought special at the local Salvation Army just for that purpose. “These cost $2,” I’d tell them. “They’re my social justice shoes. Who’s willing to trade? Oh, nobody? Why ever not?” Or I’d come to class in a plain Wal-Mart t-shirt, on which I’d written “I Heart [This University]” in Magic Marker. Same deal, I’d tell them. “The stuff you guys are wearing sends the same message, but I’ve been in the bookstore, I know for a fact that the hoodie you’re wearing [pointing to the most dolled-up Basic Becky I could find] costs $75. My shirt only cost $2. We’re both telling the world that we love [this university], but yours cost a whole lot more. You, Becky, are taking like $73 out of the mouths of poor people by wearing that … right?”

Repeat as often as needed, until they get the idea that “price” isn’t the same thing as “cost”. This isn’t physics class, I’d tell them, where we can assume away important real-world stuff like friction. Out here in the real world, we have to take stuff like “overhead” and “taxes” into account, such that even if those ugly sneakers or that crappy college-logo t-shirt only “cost” $2 at the point of manufacture, getting them onto the shelves at the the store here in College Town adds a whole bunch more. And then there’s demand, which we’ve already covered. I offered to trade y’all my shoes. Hell, I offered to give away my homemade t-shirt, and nobody took me up on it. You might change your tune if you were naked – and here we will note that this was the kind of situation Karl Marx was putatively addressing – but if you have any choice at all you’ll stick with what you have, because nobody in his right mind wants to wander around campus in a homemade t-shirt …

In short, I’d tell them, price is information. Done right – in an absolutely free market, the capital-L Libertarian paradise, which is of course as bong-addled a fantasy as Marx’s – price is perfect information. Nike’s sneakers don’t sell for $200 because that’s what it cost to make them. The $200 is the aggregate of all those costs we talked about before – cost of materials, labor, transportation, taxes, and, as we’ve seen by the fact that y’all still won’t trade me shoes, the most important piece of information, demand.

Severian, “Velocity of Information (I)”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-26.

November 13, 2023

Carefully trained and shaped hollow people

At Ricochet, David Foster talks about how today’s university students have become … hollow:

I’ve been writing for years about the rise of toxic ideologies on America’s college campuses – totalitarian, anti-Israel, outright anti-Semitic – but still have been surprised by what has happened in these places since October 7. We need to discuss the reasons why it’s gotten so bad.

A few days ago, someone republished an essay, written in 2016, by a professor who has taught at several “elite” colleges. Excerpt:

My students are know-nothings. They are exceedingly nice, pleasant, trustworthy, mostly honest, well-intentioned, and utterly decent. But their brains are largely empty, devoid of any substantial knowledge that might be the fruits of an education in an inheritance and a gift of a previous generation. They are the culmination of western civilization, a civilization that has forgotten nearly everything about itself, and as a result, has achieved near-perfect indifference to its own culture. It’s difficult to gain admissions to the schools where I’ve taught – Princeton, Georgetown, and now Notre Dame. Students at these institutions have done what has been demanded of them: they are superb test-takers, they know exactly what is needed to get an A in every class (meaning that they rarely allow themselves to become passionate and invested in any one subject); they build superb resumes. They are respectful and cordial to their elders, though easy-going if crude with their peers. They respect diversity (without having the slightest clue what diversity is) and they are experts in the arts of non-judgmentalism (at least publically). They are the cream of their generation, the masters of the universe, a generation-in-waiting to run America and the world.

And when someone has devoted the first 18 years of their lives in large part to jumping through hoops in hopes of making a good impression on some future college admissions officers … and then, in many cases, having to get good ratings from professors whose criteria are largely subjective … that someone is unlikely to develop into a person with a strong internal gyroscope. Quite likely, they are likely to be subject to social pressures and mass movements.

Someone at X said that the Cornell student arrested for making threats against Jewish students was probably just trying too hard to fit in and win approval of his peers and took it a step too far. My view is that there’s no just about it … the desire to fit in and win approval is very often the reason why people commit evil acts. I’m reminded of something CS Lewis said: “Of all the passions, the passion for the Inner Ring is most skillful in making a man who is not yet a very bad man do very bad things“.

The above sentence is from a talk that Lewis gave at King’s College in 1944. Also from that address:

And the prophecy I make is this. To nine out of ten of you the choice which could lead to scoundrelism will come, when it does come, in no very dramatic colours. Obviously bad men, obviously threatening or bribing, will almost certainly not appear. Over a drink, or a cup of coffee, disguised as triviality and sandwiched between two jokes, from the lips of a man, or woman, whom you have recently been getting to know rather better and whom you hope to know better still — just at the moment when you are most anxious not to appear crude, or naïf or a prig — the hint will come. It will be the hint of something which the public, the ignorant, romantic public, would never understand: something which even the outsiders in your own profession are apt to make a fuss about: but something, says your new friend, which “we” — and at the word “we” you try not to blush for mere pleasure — something “we always do”.

And you will be drawn in, if you are drawn in, not by desire for gain or ease, but simply because at that moment, when the cup was so near your lips, you cannot bear to be thrust back again into the cold outer world. It would be so terrible to see the other man’s face — that genial, confidential, delightfully sophisticated face — turn suddenly cold and contemptuous, to know that you had been tried for the Inner Ring and rejected. And then, if you are drawn in, next week it will be something a little further from the rules, and next year something further still, but all in the jolliest, friendliest spirit. It may end in a crash, a scandal, and penal servitude; it may end in millions, a peerage and giving the prizes at your old school. But you will be a scoundrel.

So yes, the passion for approval has always existed. But I feel sure it is much stronger, or at least has fewer countervailing forces, among people who experience today’s college admissions race and its eventual fulfillment.

The students about whom the professor wrote in the essay linked above have not only been encouraged to devote their time to hoop-jumping, they have also been told again and again that their country and their society are evil – that their ancestors were evil, and their parents are probably evil as well. And that practically all aspects of culture more than five years old, whether traditional songs and folktales or classic movies, are harmful and certainly unworthy of study except for purposes of deconstructing their bad examples. And, of course, relatively few of these students are influenced by or have seriously studied any traditional religion.

November 7, 2023

Potentially killing off Quebec’s English-language universities isn’t a bug, it’s a feature

Chris Selley on the Quebec government’s vindictive decision to massively hike tuition rates for out-of-province students of the province’s three English-language universities:

“McGill University Montreal 3” by Laslovarga is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 .

McGill, Concordia and Bishop’s universities have begun to budget for the nightmare Quebec Premier François Legault’s government has imposed on the English-language schools by doubling out-of-province tuition fees — a way to keep socially corrosive anglophones out of Montreal, the premier has said in so many words.

In an open letter Thursday, McGill principal and vice-chancellor Deep Saini suggested the policy might lead to a $94-million annual shortfall in revenue, necessitating the layoff of 700 staff and closure of certain programs (notably the Schulich School of Music) and fewer athletics teams. It depends how many international students they can recruit to replace out-of-province Canadians unwilling to splash out $17,000 a year. (Yes, those international students would also speak English. No, Legault’s plan doesn’t make any sense whatsoever.)

Concordia president Graham Carr said much the same in an internal university memo on Tuesday, estimating the Coalition Avenir Québec’s latest attack on English could cost it 10 per cent of its total budget. As for Bishop’s, a small 180-year-old liberal-arts college near Sherbrooke: “I don’t believe that Bishop’s can survive under this policy,” former university principal Michael Goldbloom said bluntly this week.

Premier François Legault says he’s willing to meet with officials from all three universities. So they’ve got that going for them, which is nice. The provincial Liberals, what’s left of them, have spoken out against the tuition grab, as has Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante.

But opposition to this in Ottawa remains utterly pathetic. “Quebec makes its own decisions, but I don’t necessarily think this is the best one,” is still the best Pablo Rodriguez, the prime minister’s Quebec lieutenant, has managed to muster. Liberal Francis Scarpaleggia, who represents a riding on Montreal’s West Island, is the only MP to have mentioned it in the House of Commons, calling it “an improvised and populist policy that is not justified.”