seangabb

Published 28 Aug 2024The Roman Empire had a geographical logic, but was an endlessly diverse patchwork of linguistic, ethnic and religious groups. In this lecture, Sean Gabb describes the diversity:

Geographical Logic – 00:00:00

Linguistic Diversity – 00:06:57

Italy – 00:12:46

Greece – 00:17:23

Greeks and Romans – 00:21:01

Egypt – 00:28:24

Greeks, Romans, Egyptians – 00:33:00

North Africa – 00:37:27

The Jews – 00:41:20

Greeks, Romans, Jews – 00:44:10

Gaul – 00:50:36

Britain – 00:52:26

Greeks, Romans, Britons – 00:54:58

The East – 00:59:22

Bibliography – 01:01:20

(more…)

February 28, 2025

Everyday Life in the Roman Empire – An Empire of Peoples

January 9, 2025

“Starmer is a banshee of a prime minister; he makes a terrible noise but is completely lacking in substance”

The extent of active disinterest to ongoing criminal activity in British towns and cities over a period of several years passes belief. The fear of being accused of racism metastasized to the extent that the authorities may even have colluded with criminals to hide the crimes to preserve politicians’ and senior bureaucrats’ careers. It’s now broken through the conspiracy of silence to being actively discussed in British media and even on the floor of the House of Commons. Even the Prime Minister may have to answer for past actions (or inactions):

It’s very easy to judge the past, particularly when you’re on the “right side of history”. What supreme confidence it must take to assume that all previous generations had got it so wrong, and that humanity was simply waiting for you to turn up and set them straight.

And yet isn’t it curious that so many who like to judge the values and behaviour of people in the past are also rarely willing to turn that critical eye on other cultures that exist today? According to the principle of cultural relativism, all societies and ways of life are equal. So we must not assert that we are morally better to a culture that permits the genital mutilation of children or that denies women an education, but we may assume that we are highly superior to the Ancient Greeks.

This debate has become particularly relevant with the recent explosion of interest in the rape gangs scandal. A report by Professor Alexis Jay in 2022 determined that more than 1,400 young girls were raped and abused in the period between 1997 and 2013 by what became known as the “grooming gangs”, so called because of the manipulative tactics that were employed to gain the victims’ trust. These groups comprised mostly of men of Pakistani heritage, which led many authorities to overlook the severity of the crimes.

Consider this example from a speech delivered by Andrew Norfolk, reporter for the Times. When police discovered a 13-year-old girl, drunk and mostly naked in the company of seven Pakistani men, they arrested her and failed to question any of the adults.

Police have admitted that such failures to investigate were largely down to a desire to avoid allegations of racism. The Jay report noted that several members of local council staff “described their nervousness about identifying the ethnic origins of perpetrators for fear of being thought as racist; others remembered clear direction from their managers not to do so”. Politicians and media commentators were more concerned with maintaining the fantasy that multiculturalism has been a success, rather than taking seriously their obligation to safeguard children. When Julie Bindel — the first journalist to investigate the grooming gangs — tried to publish her findings, she faced resistance ‘because some editors feared an accusation of racism’.

The Labour government has shown itself incapable of making amends. Jess Phillips has rejected a request for a public inquiry into child sexual exploitation in Oldham. And Keir Starmer has stated that anyone interested in a full-scale inquiry into these failings is jumping “on a bandwagon of the far right”.

This acute form of tone-deafness would, in any sound political climate, be cause for immediate resignation. While it is true that racists will be quick to weaponise the criminal behaviour of a minority, there is nothing remotely “far right” in taking an interest in the wellbeing of children and wishing to see those who abuse them held to account. But Starmer is a banshee of a prime minister; he makes a terrible noise but is completely lacking in substance.

Something may change with the release this week of crime league tables according to nationality. Up until now, there has been tremendous political resistance to releasing such statistics, with police in many European countries not recording such details at all in order to preserve the daydream of multiculturalism. And yet those that do keep such records have revealed a clear trend. Data from the Danish government, for instance, has shown that although non-Western immigrants constitute only 9% of the population, they account for 25% of convictions for violent crime. According to the Telegraph, in Sweden immigrants are “three times more likely to be registered as a suspect for assault than the native population – which grows to four times for robbery, and five times for rape”.

By happenstance, I posted this to social media the other day, which seems apposite:

January 6, 2025

The rape gangs in Britain were enabled and protected by “good people” who didn’t want to be accused of racism

Tom at The Last Ditch confesses his early complicity with the official culture of silence that protected and encouraged the exploitation of girls and young women in Britain for decades:

Everyone who ever participated in the leftist orthodoxy of identity-politics is to blame for the near-total impunity of the Muslim rape gangs in Britain. As I reported here, when I was a young solicitor in Nottingham, a police sergeant told me I was “part of the problem.” I had a choice between believing what he told me about “honour killings” in that city or preserving my good standing as an anti-racist liberal. I chose the latter. I feared my career prospects and social standing would be jeopardised (they would have been) if I accepted his honest account. I called a good man a racist (mentally equating him with the likes of Nick Griffin and recoiling in fear from the association) when he was just horrified (as any decent human should be) by young women being murdered.

In that moment, I very much was “part of the problem” and I am profoundly ashamed of that. It is fortunate that – unlike the politicians, local councillors, social-workers and police officers who should have brought the rape gangs or the “honour” killers to justice (or prevented both phenomena altogether) – I had no occasion ever to make any real life choices on the matter. I believe – faced with actual evidence – I would have made better ones, but the way I failed the good sergeant’s test that long-ago day in the early 1980s proves I would have wanted to look the other way, just as they actually did.

I am not still playing the stupid rainbows and unicorns game of cultural moral equivalence (still less the foul Critical Race Theory game of cultural moral hierarchy) when I make the point that the young white working class girls in our cities have not been the only victims of multiculturalism. Those murdered Muslim girls who (so the sergeant told me) had paraffin poured over them and were burned to death were victims too. It was racist to refuse to consider that their Muslim dads, uncles and brothers might murder them because of their primitive religious and cultural notions. It was racist for our authorities to treat Muslim men who gang-raped white girls differently than they would have treated others. It was racist to cover up these horrors in order to protect the myth – shamefully repeated just days ago in his annual Christmas message by His Majesty the King – that multiculturalism has been an overall benefit to Britain.

Some of us have been making these points as best we can for a long time. Many of us had given up, if we’re honest. It was clear that the official narrative that we were racists and that these stories were disinformation – a “moral panic” as Wikipedia puts it – was going to prevail. Until recently the key social media market of ideas – Twitter – was controlled by the Left and attempts to raise the issue were likely to be memory-holed by their private sector woke equivalent of Orwell’s MiniTru.

Miraculously, Elon Musk – a modern Edison, with plenty to occupy him besides our concerns about free speech – bought Twitter and (in one of history’s greatest acts of philanthropy) set it free at his own personal expense. He told advertisers who sought to maintain its old Newspeak regime to “go fuck themselves.” Miraculously he got involved in the issue not just in America (where the Constitution gives him some basis for hope) but in Britain too.

My British Constitution textbook at law school illustrated the supremacy of our Parliament by jokingly saying that it could – in law – make a man into a woman. Little did its authors know that dimwit politicians would later prove the educational point of their joke by making it real. Our constitution – as a result of centuries of struggle with the monarchy, which Parliament decisively won – can be summarised in just three words – “Parliament is supreme”

November 18, 2024

“The Great Canadian Lie is the claim that we’ve ‘always been multicultural'”

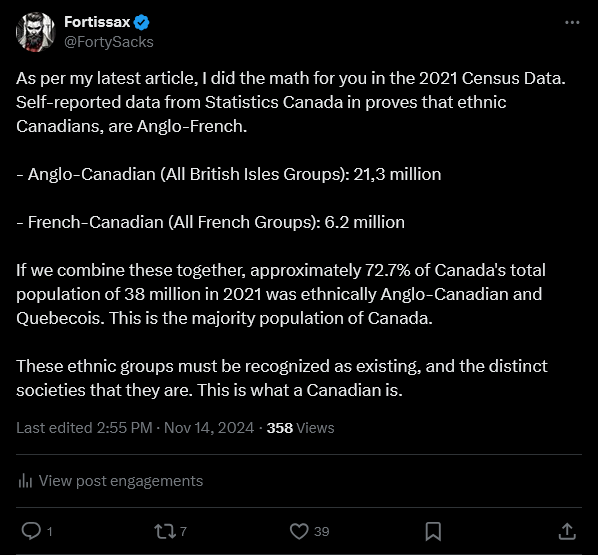

Fortissax thinks that the rest of Canada has lessons to be learned from Quebec:

If you are a Canadian born at any point in the Post-WWII era, you have been subjected to varying degrees of liberal “Cultural Mosaic” propaganda. This narrative exploits the historic presence of three British Isles ethnic groups (which had already been intermixing for millennia) and the predominantly Norman French settlers to justify the unprecedented mass migration of people from the Third World into Canada. This process only began in earnest in the 1990s before accelerating rapidly in the 2010s.

The Great Canadian Lie is the claim that we’ve “always been multicultural”, as though the extremely small and inconsequential presence of “Black Loyalists” or the historically hostile Indigenous groups (making up only 1% of the population at Canada’s founding in 1867) played any serious role in shaping the Canadian nation, its identity, institutions, or culture. Inspired by Dr. Ricardo Duchesne’s book Canada in Decay: Mass Immigration, Diversity, and the Ethnocide of Euro-Canadians (2017), which chronicled the emergence of two ethnic groups uniquely born of the New World, I delved into the 2021 Census data collected by the Canadian government to explore the ethnic breakdown of White Canadians in greater detail

The evidence is clear. In 2021, just four years ago, 72.7% of the entire Canadian population was not just White, but Anglo-Canadian and French-Canadian, representing an overwhelming presence compared to visible minorities and other White ethnic groups, such as the small populations of Germans and Ukrainians.

In the space last night, I highlighted this historical fact and explained to the audience the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Canadian and its significance. While we all recognize that the Québécois are a homogeneous group descended predominantly from Norman French settlers — such as the Filles du Roi and Samuel de Champlain’s 1608 expedition, which established Quebec City with a single-minded purpose — the Anglo-Canadian story also deserves similar recognition for its role in shaping Canada’s identity.

But what is less known is that Anglo-Canadians are just as ethnically homogeneous as the Québécois, from Nova Scotia to British Columbia. Anglo-Canadian identity emerged from Loyalist Americans in the 1750s, beginning with the New England Planters in Nova Scotia — “continentals” with a culture distinct from both England and the emergent Americans. After the American Revolutionary War, they marched north with indomitable purpose, like Aeneas and the Trojans, to rebuild their Dominion. Author Carl Berger, in his influential work The Sense of Power: Studies in the Ideas of Canadian Imperialism, demonstrates that the descendants of Loyalists were the one ethnic group that nurtured “an indigenous British Canadian feeling.” The following passage from Berger’s work is worth citing:

The centennial arrival of the loyalists in Ontario coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of the incorporation of the City of Toronto and, during a week filled with various exhibitions, July 3 was set aside as “Loyalist Day”. On the morning of that day the platform erected at the Horticultural Pavilion was crowded with civic and ecclesiastical dignitaries and on one wall hung the old flag presented in 1813 to the York Militia by the ladies of the county. Between stirring orations on the significance of the loyalist legacy, injunctions to remain faithful to their principles, and tirades against the ancient foe, patriotic anthems were sung and nationalist poetry recited. “Rule Britannia” and “If England to Herself Be True” were rendered “in splendid style” and evoked “great enthusiasm”. “A Loyalist Song”, “Loyalist Days”, and “The Maple Leaf Forever”, were all beautifully sung

The 60,000 Loyalist Americans, who arrived in two significant waves, were soon bolstered by mass settlement from the British Isles. However, British settlers assimilated into the Loyalist American culture rather than imposing a British identity on the new Canadians. The first major wave of British settlers after the Loyalists primarily consisted of the Irish. Before Confederation in 1867, approximately 850,000 Irish immigrants settled in Canada. Between 1790 and 1815, an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 settlers, mainly from the Scottish Highlands and Ireland, also made their way to Canada.

Another large-scale migration occurred between 1815 and 1867, bringing approximately 1 million settlers from Britain to Canada, specifically to Ontario, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. New Brunswick was carved out from the larger province of Nova Scotia to make room for the influx of Loyalists. During this time, settlers from England, Scotland, and Ireland intermingled and assimilated into the growing Anglo-Canadian culture. Scottish immigrants, who constituted 10–15% of this wave, primarily spoke Gaelic upon arrival but adopted English as they integrated.

All settlers from the British Isles spoke English (small numbers spoke Gaelic in case of Scots), were ethnically and culturally similar, and had much more in common with each other than with their continental European counterparts.

Settlement would slow down in the years immediately preceding Confederation in 1867 but surged again during the period between 1896 and 1914, with an estimated 1.25 million settlers yet again from Britain moving to Canada as part of internal migration within the British Empire. These settlers predominantly also [went] to Ontario and the Maritimes, further forging the Anglo-Canadian identity.

A common misconception among Canadians is that Canada “was a colony” of Britain, subordinate to, or a “vassal state”. This is wrong. Canadians were the British, in North America. There were no restrictions on what Canadians could or could not do in their own Dominion. From the first wave of Loyalists onward, Canadians were regularly involved in politics and governance, actively participating in shaping the nation.

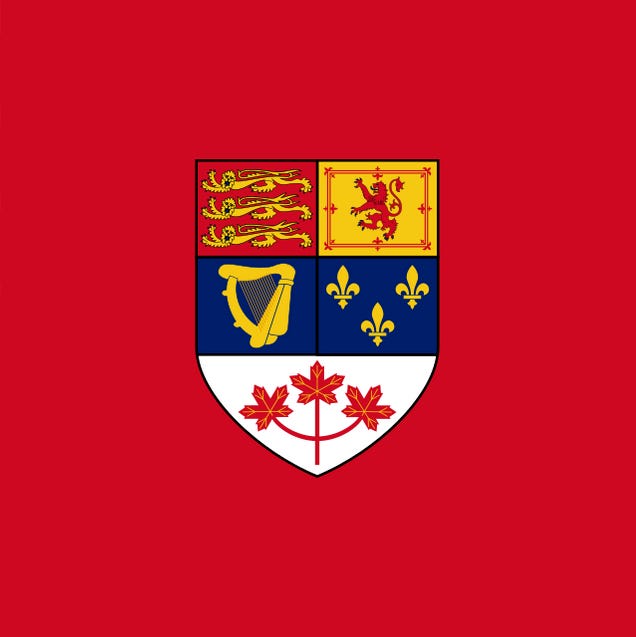

Like the ethnogenesis of the English, which saw Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians converge into a new people and ethnicity (the Anglo-Saxons), Anglo-Canadians are a combination of 1.9 million English, 850,000 Irish (from both Northern and Southern Ireland), and 200,000 Scots, converging with 60,000 Loyalist Americans from the 13 Colonies. These distinct yet similar ethnic groups no longer exist as separate peoples in Canada. Anglo-Canadians are the fusion of the entire British Isles. The Arms of Canada, the favourite symbol of Canadian nationalists today, represents this new ethnic group with the inclusion of the French:

It’s no coincidence that, once rediscovered, the Arms of Canada exploded in popularity as the emblem of Canadian nationalists. Unlike more controversial symbols that appeal to pan-White racial unity, such as the Sonnenrad or Celtic cross, the Arms of Canada resonate as a distinctly Canadian icon, deeply rooted in the nation’s true heritage and history — a heritage that cannot be bought, sold, or traded away. This is an immutable bloodline stretching into the ancient past. If culture is downstream from race, and deeper still, ethnicity, then Canadian culture, values, and identity are fundamentally tied not just its race, but its ethnic composition. The ethnos defines the ethos. Canadians are not as receptive to the abstract idea of White nationalism for the same reason Europeans aren’t — because they possess a cohesive ethnic identity, unlike most White Americans.

October 29, 2024

QotD: The Roman Republic after the Social War

The Social War coincided with the beginning of Rome’s wars with Mithridates VI of Pontus – the last real competitor Rome had in the Mediterranean world, whose defeat and death in 63 BC marked the end of the last large state resisting Rome and the last real presence of any anti-Roman power on the Mediterranean littoral. Rome was not out of enemies, of course, but Rome’s wars in the decades that followed were either civil wars (the in-fighting between Rome’s aristocrats spiraling into civil war beginning in 87 and ending in 31) or wars of conquest by Rome against substantially weaker powers, like Caesar’s conquests in Gaul.

Mithridates’ effort against the Romans, begun in 89 relied on the assumption that the chaos of the Social War would make it possible for Mithridates to absorb Roman territory (in particular the province of Asia, which corresponds to modern western Turkey) and eventually rival Rome itself (or whatever post-Social War Italic power replaced it). That plan collapsed precisely because Rome moved so quickly to offer citizenship to their disgruntled socii; it is not hard to imagine a more stubborn Rome perhaps still winning the Social War, but at such cost that it would have had few soldiers left to send East. As it was, by 87, Mithridates was effectively doomed, poised to be assailed by one Roman army after another until his kingdom was chipped away and exhausted by Rome’s far greater resources. It was only because of Rome’s continuing domestic political dysfunction (which to be clear had been going on since at least 133 and was not a product of the expansion of citizenship) that Mithridates lasted as long as he did.

More than that, Rome’s success in this period is clearly and directly attributable to the Roman willingness to bring a wildly diverse range of Italic peoples, covering at least three religious systems, five languages and around two dozen different ethnic or tribal identities and forge that into a single cohesive military force and eventually into a single identity and citizen body. Rome’s ability to effectively manage and lead an extremely diverse coalition provided it with the resources that made the Roman Empire possible. And we should be clear here: Rome granted citizenship to the allies first; cultural assimilation only came afterwards.

Rome’s achievement in this regard stands in stark contrast to the failure of Rome’s rivals to effectively do the same. Carthage was quite good at employing large numbers of battle-hardened Iberian and Gallic mercenaries, but the speed with which Carthage’s subject states in North Africa (most notably its client kingdom, Numidia) jumped ship and joined the Romans at the first real opportunity speaks to a failure to achieve the same level of buy-in. Hannibal spent a decade and a half trying to incite a widespread revolt among Rome’s Italian allies and largely failed; the Romans managed a far more consequential revolt in Carthage’s North African territory in a single year.

And yet Carthage did still far better than Rome’s Hellenistic rivals in the East. As Taylor (op. cit.) documents, despite the vast wealth and population of the Ptolemaic and Seleucid states, they were never able to mobilize men on the scale that Rome did and whereas Rome’s allies stuck by them when the going got tough, the non-Macedonian subjects of the Ptolemies and Seleucids always had at least one eye on the door. Still worse were the Antigonids, whose core territory was larger and probably somewhat more populous than the ager Romanus (that is, the territory directly controlled by Rome), but who, despite decades of acting as the hegemon of Greece, were singularly incapable of directing the Greeks or drawing any sort of military resources or investment from them. Lest we attribute this to fractious Greeks, it seems worth noting that the Latin speaking Romans were far better at getting their Greeks (in Southern Italy and Campania) to furnish troops, ships and supplies than the Greek speaking (though ethnically Macedonian) Antigonids ever were.

In short, the Roman Republic, with its integrated communities of socii and relatively welcoming and expansionist citizenship regime (and yes, the word “relatively” there carries a lot of weight) had faced down a collection of imperial powers bent on maintaining the culture and ethnic homogeneity of their ruling class. Far from being a weakness, Rome’s opportunistic embrace of diversity had given it a decisive edge; diversity turned out to be the Romans’ “killer app”. And I should note it was not merely the Roman use of the allies as “warm bodies” or “cannon fodder” – the Romans relied on those allied communities to provide leadership (both junior officers of their own units, but also after citizenship was granted, leadership at Rome too; Gaius Marius, Cicero and Gnaeus Pompey were all from communities of former socii) and technical expertise (the Roman navy, for instance, seems to have relied quite heavily on the experienced mariners of the Greek communities in Southern Italy).

Like the famous Appian Way, Rome’s road to empire had run through not merely Romans, but Latins, Oscan-speaking Campanians, upland Samnites, Messapic-speaking Apulians and coastal Greeks. The Romans had not intended to forge a pan-Italic super-identity or to spread the Latin language or Roman culture to anyone; they had intended to set up systems to get the resources and manpower to win wars. And win wars they did. Diversity had won Rome an empire. And as we’ll see, diversity was how they would keep it.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-25.

September 28, 2024

The rise in niqab and hijab use among Muslim women in Britain

In The Conservative Woman, Gillian Dymond discusses the cultural significance of Muslim women’s distinctive styles of clothing in modern Britain:

AS I WENT to the shops the other day in Whitley Bay, a strangely incongruous figure passed me. It was a woman in a niqab. In a recent article on his Substack, Joshua Trevino wrote an elegy for London: “I had not seen this many women in hijabs since a brief stint working in Jordan decades ago, and I had never seen this many women in a niqab, ever.” Up here on the north-east coast of England, it is different. True, even in Newcastle hijabs proliferate, but I had never before encountered the full niqab there, let alone in the small seaside town where I live.

The Government, I understand, are considering bringing in a law which would criminalise Islamophobia, as defined by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims. “Islamophobia,” this states, “is rooted in racism and is a type of racism that targets expressions of Muslimness or perceived Muslimness“.

This, as Andrew Doyle points out here, is nonsense, incorrectly conflating a belief-system with racial identity. Let’s be accurate: Muslims can be of any race, English included. Moreover, different Muslims exhibit different kinds and degrees of “Muslimness”, from the Sufi, mystically seeking the divine, through the undogmatic, many of whom happily dispense with headscarf and hijab and the more bellicose interpretations of the holy books, to the kind of male fanatic who, on seeing a female co-religionist wearing Western dress and sporting lipstick, seizes her by the hair and slams her head on the dashboard of the car she has been shamelessly driving.

There is a variety of “Muslimness”, in short, whose intolerance cannot be tolerated in a tolerant society, and whose existence requires not protective legislation, but public acknowledgement of its incompatibility with the British way of life.

I do not know how the woman whose eyes peered through the slit in her black draperies felt about parading her glaring lack of integration on a street in north-east England. Did she go proudly and self-righteously into the alien throng, or had she been forced out of the house, heart pounding, to run the gauntlet of raised eyebrows in her eye-catching gear? What did she think of the women around her, hair and faces exposed, arms bare to soak up every last ray of autumnal sunshine, some of them, fresh from the beach, wearing shorts? Did she despise their “immodesty”? Did she envy them?

Who knows? There can be no casual breaching of the niqab’s anonymity, no spontaneous communication, when confronted by a garment which puts up barricades against the usual signals and responses of easy human intercourse.

On the other hand, the mentality of the men who insist on enveloping their wives and daughters head-to-foot in long black shrouds before they are allowed out in public is very clear indeed. These men have been taught to view women as assets to be protected, and they no doubt believe that the heavy-handed protection they impose is necessary, because they take it for granted that no man is able, or should be expected, to control his sexual urges in the face of female allurements. As for any woman who does not remain decently covered in deference to the male’s helpless susceptibility, she should know the consequences, and deserves everything coming to her.

August 9, 2024

Domicidal maniacs in charge

Lorenzo Warby provides an oh-so-useful word to accurately capture what the diversity-at-all-costs elites running most western countries these days are actually up to:

Domicide is the destruction of home. It comes in the “hard” version — the physical destruction of houses and infrastructure.

Domicide also comes in a “soft” version — flooding localities with new people, separating people from, and otherwise degrading, their heritage. When folk say Britain is becoming “unrecognisable”, it is the domicidal effect of mass migration they are referring to.

The UK is suffering from a domicidal elite, one that uses mass migration to break up working-class communities; asymmetric multiculturalism to elevate incoming cultures over those of native English (the Celtic fringe get minority brownie points); favours non-“white” faces in advertising; asymmetric race-swapping in entertainment against the native English; denigration of British history as racist, white supremacist, imperialist, colonialist, etc.

Much of this is insulting virtue-signalling allied to, or presenting, cartoonish (simplified) and caricature (distorted) history. It all undermines social cohesion. But it is the use of migration policy as a systematic weapon against the resident working class which does the most damage. Though two-tier policing — obviously treating Muslims in particular with a deference not shown to the natives, especially when it comes to policing speech — is also highly corrosive of social cohesion.

Many working-class communities in Britain were already fairly dysfunctional — though the British state is not innocent in those dysfunctions1 — and sections of the British working class are very far from admirable. None of this justifies the use of mass migration to make things worse for such folk, however much it may help to explain the moralised class contempt that underlies so much of modern progressivism and modern managerialism.

To improve such things, to “level up”, requires a strong sense of how to create and maintain social order. Modern progressivism is strongly antipathetic to such understanding. To “level up” also requires a strong sense of custodianship, which managerialism typically lacks: particularly progressivist managerialism.

Indeed, modern feminist, progressivist, managerialism—in its lack of custodianship; lack of social solidarity;2 in its antipathy to taking the problems of social order seriously — is running the British state into the ground. The post-medieval British aristocratic and mercantile elite did a much better job of state management. But those elites had mechanisms — such as duelling, that forced men to defend their reputation at the risk of their life, and grand country houses, that turned into expensive investments in social isolation if you behaved badly — that selected for character.

Nowadays, the British elite only selects for capacity and even that is being degraded by DEI undermining the signals of competence. It turns out, over the longer term, character matters more than capacity. For capacity without character selects for manipulative, anti-social personalities that degrade institutions over time.

1. For a particularly brutal depiction in fiction of the dysfunctional British welfare state — especially its school system — see Christopher Nuttall’s Mystic Albion series, especially the first book.

2. Feminisation of institutions and discourse has tended to degrade social solidarity, see Benenson et al, 2009. The most conspicuous example of this in the UK is how uncouth it is in elite circles to mention the systematic rape and sexual exploitation of underage working class girls by overwhelmingly Muslim gangs.

August 3, 2024

“Multiculturalism is when yummy food”

Fortissax pours scorn on the defenders of multiculturalism-at-all-costs for one of the most common arguments in favour:

“Multiculturalism is when yummy food” is a real position people take. If you ask them what benefits of multiculturalism are, they’re going to say food and nothing else. Westerners don’t watch Bollywood films, they don’t listen to Desi music, they don’t watch cartoonishly bad Latin American dramas, usually for Hispanic abuelas still living in Mexico where every actor is suspiciously fairer-featured than everyone in their whole family. People can’t say “I love the food, the music, the culture” because they don’t engage in any of this. Salsa isn’t even popular; it hit its peak at the end of the 1990s because white boomer Americans approached an intensely Anglicised, sanitised form of Latin-American culture as introduced to them through the likes of Enrique Iglesias and other English-speaking Latin pop artists.

I don’t believe all leftists say this out of sincerity. It’s a knee-jerk reaction to any criticism of multiculturalism. They don’t put a lot of thought into it. The justification is usually related to how “bad” that “white people food” is. This follows the same thread of accusations that “white people can’t dance”, “white people can’t jump”, “white people can’t fight”, and “white people can’t fuck”. It’s another lib-coded tract to bash English-speaking white Americans over the head with, to justify demographic displacement by portraying them as boring, ugly, weird, or uncool. On some level, they probably know food isn’t worth human lives, but they have to reinforce their moral view or the whole thing collapses, and they have to admit fault for doing things and promoting ideas that are so destructive that people would want to unalive them. If they give up now, it’s over. It’s sunk cost fallacy.

For the rest who’re wholly sincere: it’s just straight up bullshit. Foreign restaurants serve you a Westernized version of their slop. Their bulk food suppliers are Western, the ingredients are Western-derived, but they sell it as “authentic” when it isn’t. That crab rangoon you just spent $40 on Doordash was bulk bought at Costco during a last ditch grocery run. They’re selling you the experience. A sampling of the real thing, deliberately fitted to your people’s general dietary preferences. All of these “ethnic”, “exotic” restaurants do this. Everyone knows about “secret menus” at Chinese or Indian restaurants. Anybody who works in culinary, hell, anybody whose watched the UK version of Hell’s Kitchen where Gordan Ramsay tries to rescue failing restaurants owned by small business owners can tell you most of these people aren’t using fresh or original ingredients. You go to any “Japanese” restaurant in North America, the staff are a random assortment of Asian, or sometimes Korean or Chinese, or maybe even Filipino but it doesn’t matter because they look Asian enough to boomers, correctly guessing people can’t tell the difference at a passing glance.

July 30, 2024

QotD: The Roman Republic and the Social War

Rome’s tremendous run of victories from 264 to 168 (and beyond) fundamentally changed the nature of the Roman state. The end of the First Punic War (in 241) brought Rome its first overseas province, Sicily which wasn’t integrated into the socii-system that prevailed in Italy. Part of what made the socii-system work is that while Etruscans, Romans, Latins, Samnites, Sabines, S. Italian Greeks and so on had very different languages, religions and cultures, centuries of Italian conflict (and then decades of service in Rome’s armies) had left them with fairly similar military systems, making it relatively easy to plug them in to the Roman army. Moreover, being in Rome’s Italian neighborhood meant that Rome could simply inform the socii of how many troops they were expected to supply that year and the socii could simply show up at the muster at the appointed time (which is how it worked, Plb. 6.21.4). Communities on Sicily (or other far-away places) couldn’t simply walk to the point of muster and might be more difficult to integrate into core Roman army. Moreover, because they were far away and information moves slowly in antiquity, Rome was going to need some sort of permanent representative present in these places anyway, in a way that was simply unnecessary for Italian communities.

Consequently, instead of being added to the system of the socii, these new territories were organized as provinces (which is to say they were assigned to the oversight of a magistrate, that’s what a provincia is, a job, not a place). Instead of contributing troops, they contributed taxes (in money and grain) and the subordination of these communities was much more direct, since communities within a province were still under the command of a magistrate.

We’ll get to the provinces and their role in shaping Roman attitudes towards identity and culture a bit later, but for the various peoples of Roman Italy, the main impact of this shift was to change the balance of rewards for military service. Whereas before most of the gains of conquest were in loot and land – which the socii shared in – now Roman conquests outside of Italy created permanent revenue streams (taxes!) which flowed to Rome only. Roman politicians began attempting to use those revenue streams to provide public goods to the people – land distribution, free military equipment, cheap grain – but these benefits, provided by Rome to its citizens, were unavailable to the socii.

At the same time, as the close of the second century approached, it became clear that the opportunity to march up the ladder of status was breaking down, consumed by the increasingly tense maelstrom of the politics of the Republic. In essence while it was obvious as early as the 120s (and perhaps earlier) that a major citizenship overhaul was needed which would extend some form of Roman citizenship to many of the socii, it seems that everyone in Rome’s political class was conscious that whoever actually did it would – by virtue of consolidating all of those new citizens behind them as a political bloc – gain immensely in the political system. Consequently, repeated efforts in the 120s, the 100s and the 90s failed, caught up in the intensifying gridlock and political dysfunction of Rome in the period.

Consequently, just as Rome’s expanding empire had made citizenship increasingly valuable, actually getting that citizenship was made almost impossible by the gridlock of Rome’s political system gumming up the works of the traditional stepwise march up the ladder of statuses in the Roman alliance.

Finally in 91, after one last effort by Livius Drusus, a tribune of the plebs, failed, the socii finally got fed up and decided to demand with force what decades of politics had denied them. It should be stressed that the motivations behind the resulting conflict, the Social War (91-87), were complex; some Italians revolted for citizenship, some to get rid of the Romans entirely. The sudden uprising by roughly half of the socii at last prompted Rome to act – in 90, the Romans offered citizenship to all of the communities of socii who had stayed loyal (as a way of keeping them so). That offer was quickly extended to rebellious socii who laid down arms and rejoined the Romans. The following year, the citizenship grant was extended to communities which had missed the first one. The willingness to finally extend citizenship won Rome the war, as the socii who had only wanted equality with the Romans, being offered it, switched sides to get it, leaving only a handful of the hardest cases (particularly the Samnites, who never missed an opportunity to rebel against Rome) isolated and vulnerable.

The consequence of the Social War was that the slow process of minting new citizens or of Italian communities slowly moving up the ladder of status was radically accelerated in just a few years. In 95 BC, out of perhaps five million Italians, perhaps one million were Roman citizens (including here men, women and children). By 85 BC, perhaps four million were (with the remainder being almost entirely enslaved persons); the number of Roman citizens had essentially quadrupled overnight. Over time, that momentous decision would lead to a steady cultural drift which would largely erase the differences in languages, religion and culture between the various Italic peoples, but that had not happened yet and so confronted with brutal military necessity, the Romans had once again chose victory through diversity, rather than defeat through homogeneity. The result was a Roman citizen body that was bewilderingly diverse, even by Roman standards.

(Please note that the demographic numbers here are very approximate and rounded. There is a robust debate about the population of Roman Italy, which it isn’t worth getting in to here. For anyone wanting the a recent survey of the questions, L. de Ligt, Peasants, Citizens and Soldiers: Studies in the Demographic History of Roman Italy 225 BC – AD 100 (2012) is the place to start, but be warned that Roman demography is pretty technical and detail oriented and functionally impossible to make beginner-friendly.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-25.

July 18, 2024

An elite luxury belief – “Diversity Is Our Strength”

In a guest-post at Postcards from Barsoom, Spaceman Spiff lists some of the cargo cult notions that have captured the imagination of many “elites” in western nations, like “Diversity Is Our Strength“:

Multiculturalism is pursued in Western countries with a religious mania. It is difficult to imagine anything closer to a belief system for today’s upwardly mobile professional than advocating for diversity and inclusion.

Most of the world views ethnic and cultural mixing as a dangerous, civilization ending activity. A threat to be guarded against, not an opportunity to be embraced. This has been the conventional view throughout history in almost every society.

The modern Western formulation has challenged this. Mixing cultures, especially those hostile to assimilation, is not just to be tolerated but encouraged. Alien peoples must be sought out and imported to increase the ethnic and cultural mix. We must extend every courtesy to those fundamentally incompatible with us in customs and manners. The ultimate expression of this ambition is open borders, a concept viewed with deep hostility by almost all non-Western countries.

Whatever the origins of such policies, the implementers of these ideas are everywhere. They work in corporations, public sector bodies, and NGOs. We find them in Starbucks and Walmart. Diversity is everywhere even though it makes little sense as an end in itself.

How do we explain the enthusiasm with which middle managers and HR workers have embraced such a destructive idea, including its corporate version of job and education quotas?

Competency itself can be hard to find even in ideal conditions, so why hobble your chances like this? Why intentionally seek to create brittle heterogeneous environments that reduce productivity and increase strife?

The simple answer is that sophisticates don’t succumb to primitive notions like preferring their own. These are urges to be resisted, like hunger while dieting. Racism is old hat and any noticing of differences is racism. After all, our elites do not behave like this, so the goal is to be observably anti-racist, just like them.

Some look at our globalist elites and see them mixing with an international set. As they hobnob around the world they certainly socialize with foreigners. Indian elites, Arab elites, and Chinese elites all mix with their Western equivalents. We see them at events like Davos or the global climate change meetings. A multicoloured constellation of traitors from every country, all getting along with each other because they are nothing like their fellow countrymen, and everything like each other.

What the dullards in the corporate HR world miss is that this is not a celebration of diversity. Most of those elites are nearly identical. Many attended the same universities. All speak English, the international language. They have similar views, including contempt for their respective compatriots.

There is no diversity at the very top, just an elitist outlook most of them share, and contempt for the peasants who surround them. White, brown, or black, we all look the same from the cultural stratosphere. Cannon fodder for their Olympian ideas, but nothing more. The elite view of mass migration is indifference, not enthusiasm.

The street-level version takes the superficial aspects of this phenomenon and worships it as the end goal since the underlying homogeneity of the elites is largely absent. Their goal is not to seek out that which we have in common with others but the less sophisticated observation of what makes us different, what makes us more “diverse.”

The midrange talent in the West have therefore convinced themselves celebrating overt differences in the form of multiculturalism is modernity. It is the future promised by Star Trek and other communist dreams. Colour won’t matter, just like Martin Luther King promised, so long as we overlook the long predicted consequences of their dream, the lowered wages, the erosion of trust and the eventual polarization of competing groups within our own nations we once kept at bay with more considered immigration policies.

June 18, 2024

QotD: The peoples incorporated or “allied” to Rome in the Republic’s Italian expansion

In one way, pre-Roman Italy was quite a lot like Greece: it consisted of a bunch of independent urban communities situated on the decent farming land (that is the lowlands), with a number of less-urban tribal polities stretching over the less-farming-friendly uplands. While pre-Roman urban communities weren’t exactly like the Greek polis, they were fairly similar. Greek colonization beginning in the eighth century added actual Greek poleis to the Italian mix and frankly they fit in just fine. On the flip side, there were the Samnites, a confederation of tribal communities with some smaller towns occupying mostly rough uplands not all that dissimilar to the Greek Aetolians, a confederation of tribal communities and smaller towns occupying mostly rough uplands.

In one very important way, pre-Roman Italy was very much not like Greece: whereas in Greece all of those communities shared a single language, religion and broad cultural context, Roman Italy was a much more culturally complex place. Consequently, as the Romans slowly absorbed pre-Roman Italy into the Roman Italy of the Republic, that meant managing the truly wild variety of different peoples in their alliance system. Let’s quickly go through them all, moving from North to South.

The Romans called the region south of the Alps but north of the Rubicon River Cisalpine Gaul and while we think of it as part of Italy, the Romans did not. That said, Gallic peoples had pushed into Italy before and a branch of the Senones occupied the lands between Ariminum and Ancona. Although Gallic peoples were always a factor in Italy, the Romans don’t seem to have incorporated their communities as socii; indeed the Romans were generally at their most ruthless when it came to interactions with Gallic peoples (despite the tendency to locate the “unassimilable” people on the Eastern edge of Rome’s empire, it was in fact the Gauls that the Romans most often considered in this way, though as we will see, wrongly so). That’s not to say that there was no cultural contact, of course; the Romans ended up adopting almost all of the Gallic military equipment set, for instance. In any event, it wouldn’t be until the late first century BCE that Cisalpine Gaul was merged into Italy proper, so we won’t deal too much with the Gauls just yet. I do want to note that, when we are thinking about the diversity of the place, even to speak of “the Gauls” is to be terribly reductive, as we are really thinking of at least half a dozen different Gallic peoples (Senones, Boii, Inubres, Lingones, etc) along with the Ligures and the Veneti, who may have been blends of Gallic and Italic peoples (though we are more poorly informed about both than we’d like).

Moving south then, we first meet the Etruscans, who we’ve already discussed, their communities – independent cities joined together in defensive confederations before being converted into allies of the Romans – clustered on north-western coast of Italy. They had a language entirely unrelated to Latin – or indeed, any other known language – and their own unique religion and culture. The Romans adopted some portions of that culture (in particular the religious practices) but the Etruscans remained distinct well into the first century. While a number of Etruscan communities backed the Samnites in the Third Samnite War (298-290 BC) culminating in the Battle of Sentinum (295) as a last-ditch effort to prevent Roman hegemony over the peninsula, the Etruscans subsequently remained quite loyal to Rome, holding with the Romans in both the Second Punic and Social Wars. It is important to keep in mind that while we tend to talk about “the Etruscans” (as the Romans sometimes do) they would have thought of themselves first through their civic identity, as Perusines, Clusians, Populinians and so on (much like their Greek contemporaries).

Moving further south, we have the peoples of the Apennines (the mountain range that cuts down the center of Italy). The people of the northern Apennines were the Umbri (that is, Umbrian speakers), though this linguistic classification hides further cultural and political differences. We’ve met the Sabines – one such group, but there were also the Volsci and Marsi (the latter particularly well known for being hard fighters as allies to Rome; Appian reports that the Marsi had a saying prior to the Social War, “No Triumph against the Marsi nor without the Marsi”). Further south along the Apennines were the Oscan speakers, most notably the Samnites (who resisted the Romans most strongly) but also the Lucanians and Paelignians (the latter also get a reputation for being hard fighters, particularly in Livy). The Umbrian and Oscan language families are related (though about as different from each other as Italian from Spanish; they and Latin are not generally mutually intelligible) and there does seem to have been some cultural commonality between these two large groups, but also a lot of differences. Their religion included a number of practices and gods unknown to the Romans, some later adopted (Oscan Flosa adapted as Latin Flora, goddess of flowers) and some not (e.g. the “Sacred Spring” rite, Strabo 5.4.12).

Also Oscan speakers, the Campanians settled in Campania (surprise!) at some early point (perhaps around 1000-900 BC) and by the fifth century were living in urban communities politically more similar to Latium and Etruria (or Greece, which will make sense in a moment) than their fellow Oscan speakers in the hills above, to the point that the Campanians turned to Rome to aid them against the also-Oscan-speaking Samnites. The leading city of the Campanians was Capua, but as Fronda (op. cit.) notes, they were meaningful divisions among them; Capua’s very prominence meant that many of the other Campanians were aligned against it, a division the Romans exploited.

The Oscans struggled for territory in Southern Italy with the Greeks – told you we’d get to them. The Greeks founded colonies along the southern part of Italy, expelling or merging with the local inhabitants beginning in the seventh century. These Greek colonies have distinctive material culture (though the Italic peoples around them often adopted elements of it they found useful), their own language (Greek), and their own religion. I want to stress here that Greek religion is not equivalent to Roman religion, to the point that the Romans are sticklers about which gods are worshipped with Roman rites and which are worshipped with the ritus graecus (“Greek rites”) which, while not a point-for-point reconstruction of Greek rituals, did involve different dress, different interpretations of omens, and so on.

All of these peoples (except the Gauls) ended up in Rome’s alliance system, fighting as socii in Rome’s wars. The point of all of this is that this wasn’t an alliance between, say, the Romans and the “Italians” with the latter being really quite a lot like the Romans except not being from Rome. Rather, Rome had constructed a hegemony (an “alliance” in name only, as I hope we’ve made clear) over (::deep breath::) Latins, Romans, Etruscans, Sabines, Volsci, Marsi, Lucanians, Paelignians, Samnites, Campanians, and Greeks, along with some people we didn’t mention (the Falisci, Picenes – North and South, Opici, Aequi, Hernici, Vestini, etc.). Many of these groups can be further broken down – the Samnites consisted of five different tribes in a confederation, for instance.

In short, Roman Italy under the Republic was preposterously multicultural (in the literal meaning of that word) … and it turns out that’s why they won.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-06-25.

June 7, 2024

Nigel Farage’s challenge to the Conservatives

Ed West perhaps goes a bit far in comparing Nigel Farage and his Reform UK to Lenin’s Bolsheviks in the October Revolution, but he’s not wrong about what the rise of Farage’s party might mean to the already dim re-election hopes of Rishi Sunak’s bedraggled clown posse:

“Nigel Farage” by Michael Vadon is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

I imagine that the last remaining serotonin emptied from the bodies of the Tory election team when they heard that Nigel Farage was to return as leader of the Reform Party and stand at Clacton.

The likelihood is that Farage will win that seat, and the reception he received was certainly electric. And Clacton is not even among Reform’s top 20 targets, according to Matt Goodwin.

It’s possible that the party could overtake the Tories in some polls, although I doubt that they will beat them on election day. That is certainly Farage’s aim, and as he said on Monday: “I genuinely believe we can get more votes in this election than the Conservative Party. They are on the verge of total collapse … I’ve done it before. I’ll do it again. I will surprise everybody.”

Contrary to the jokes about Farage failing to get elected, or the criticism that he is a “serial loser“, he is arguably the most successful politician of the past decade. He built up a minuscule party of ‘fruitcakes and gadflies’ to win two successive European elections. He made Brexit happen, and then stood his candidates down in a number of seats to ensure the Leave alliance remained united in 2019, securing Boris Johnson a victory.

For which he didn’t get the thanks he felt was due, something he alluded to at Monday’s press conference. From what I understand the Tory establishment treated him with a snooty disdain which many an outsider has experienced with the British upper class. And for those making the old point that Farage’s private school background bars him from being a true outsider, that’s not how high society works. Populist movements claiming to represent the downtrodden or disenfranchised have invariably been led by people from highly educated or privileged backgrounds, whether of the Left or Right.

Farage’s targeted constituency certainly fits that bill. Clacton is the town that Matthew Parris called “Britain on crutches” in a piece warning the Tories not to desert their traditional middle-class voters. But the problem for the party is that, through a combination of authoritarian vibes and very liberal policies, they have managed to lose both. Rather than making moderate, soothing sounds while using the British executive’s immense power to shape the country around their will, they have done the exact opposite.

The Government’s disastrous polling figures are not some great mystery. Conservatives don’t tend to have the same emotional attachment to their party as the Labour family does. They vote Tory because they want them to do three things: cut immigration, put more criminals away, and lower taxes. It’s nothing more complicated than that, and they’ve failed on all three.

It is obviously the former that has provoked the most bitterness towards the party. I’m a great believer in Stephen Davies’s analysis of alignment in politics, and the central issue in British politics is immigration, multiculturalism and diversity. Labour are unquestionably on one side of this issue; the Tories are broadly pro-multiculturalism and, while issuing soundbites critical of high immigration, have raised it to record levels. If both main parties are seen to be on one side, something else will fill that gap in the market. Political parties are amoral bodies seeking voting coalitions, and the side which is most united in aligning its core groups around primary and secondary issues will win.

May 23, 2024

“[O]fficial justifications for mass migration often have a creepy, post-hoc flavour about them”

While it sometimes seems that there can’t possibly be mass migration issues other than here in Canada and along the US southern border, eugyppius reminds us that all of the Kakistocrats in western countries are fully in favour of more, and more, and even more inflow without restriction:

An asylum seeker, crossing the US-Canadian border illegally from the end of Roxham Road in Champlain, NY, is directed to the nearby processing centre by a Mountie on 14 August, 2017.

Photo by Daniel Case via Wikimedia Commons.

You might have noticed that mass migration to the West is a huge problem.

It is very bad for native Westerners, because it promises to transform our societies utterly, in permanent ways and not for the better. Curiously, it is also far from great for the centre-left political establishment responsible for promoting mass migration, because it has inspired a vast wave of popular opposition and filled the sails of right-leaning, migration restrictionist parties with new wind. Mass migration is also bad for taxpayers, for domestic security, for the welfare state, for many other aspects of the postwar liberal agenda and for our own future prospects. In short, mass migration is bad for almost everybody and everything.

There is a reason that nations have borders, and this is much the same reason that we have skin and that cells have membranes. You won’t survive for very long if you can’t control what enters you.

Despite the obvious fact that mass migration is bad, our rulers cling to migrationism like grim death. Given a choice between disincentivising asylees and intimidating, browbeating and harassing the millions of anti-migrationists among their own citizens, our governments generally choose the latter path, even though it is obviously the worse of the two.

Additionally unsettling, is the fact that official justifications for mass migration often have a creepy, post-hoc flavour about them. They sound much more like excuses dreamed up after the borders had already been opened, rather than any kind of reason mass migration must occur. When the migrationists really started to go crazy in 2015, for example, we were told that border security was simply impossible in the modern world and that infinity migrants were a force of nature we would have to deal with. That didn’t sound right even at the time, and since the pandemic border closures we no longer hear the inevitability narrative very much, although – and this is very bizarre to type – there is some evidence that high political figures like Angela Merkel believed it at the time. It is well worth thinking about why that might have been the case.

Another excuse that doesn’t make very much sense, is what I’ll call the refugee thesis. We’re told that millions of poor people are forced to endure terrible conditions in the developing world and that it is our moral burden to improve their lot by granting them residence in our countries. That might convince a few teenage girls, but it cannot withstand scrutiny among the rest of us. To begin with, the population of global unfortunates is enormous; the millions of refugees we have already accepted, and the millions that our politicians hope to welcome in the coming years, represent but a vanishing minority – a rounding error – compared to the vast sea of human suffering. It is like trying to solve homelessness by demanding that those in the wealthiest neighbourhoods make their spare bedrooms available to the indigent. Even more telling, however, is that the push to welcome migrants comes precisely as conditions in the developing world have dramatically improved. When things were much worse, we sealed our borders against the global south; now that they are much better, we hear all about how unacceptably inhumane it is to leave the migrants in their native lands.

Other post-hoc arguments, especially those falling in the yay-multiculturalism category, are even less serious. That we need more diversity to “spark innovation” (whatever that means) or that our local cuisines stand to benefit from the spices of the disadvantaged, are excuses of such towering stupidity, that you will lose brain cells thinking about them. As with the refugee narrative, nobody said crazy stuff like this until the migrants had already begun arriving on our shores. And there is another thing to notice about the multiculticult too. This is its blatant flippancy. The premise seems to be that migration is no big deal bro, but also too there are these cool exciting and totally random upsides, like improved local Ethiopian food offerings. It is the very definition of damning with faint praise.

The rest, sadly, is behind the paywall.

The “post-national” entity formerly known as “Canada”

You have to hand it to the Trudeau family (and all their sycophantic enablers in the legacy media, of course). What other Canadian family has had such an impact on the country? By the time Justin Trudeau’s successor is invited to form a government, Canada will have changed so much — to the point that he could describe us as the first “post-national” country thanks to his unceasing effort to destroy the nation. At The Hub, Eric Kaufmann points the finger at Trudeau’s “Liberal-left extremism” as the motivating factor in Trudeau’s career:

Justin Trudeau has always had a strong affinity for the symbolic gesture, especially when the media are around to record it.

Canada is currently suffering from left-liberal extremism the likes of which the world has never seen. This excess is not socialist or classically liberal, but specifically “left-liberal”. It is evident in everything from this country’s world record immigration and soaring rents to state-sanctioned racial discrimination in hiring and sentencing, to the government-led shredding of the country’s history and memory. Rowing back from this overreach will not be the work of voters in one election, but of generations of Canadians.

The task is especially difficult in Canada, because, after the 1960s, the country (outside of Quebec) transferred its soul from British loyalism to cultural left-liberalism. Its new national identity (multiculturalist, post-national, with no “core” identity) was based on a quest for moral superiority measured using a left-liberal yardstick. Canada was to be the most diverse, most equitable, most inclusive nation in world history. No rate of immigration, no degree of majority self-abasement, no level of minority sensitivity, would ever be too much.

In my new book The Third Awokening, I define woke as the making sacred of historically marginalized race, gender, and sexual identity groups. Woke cultural socialism, the idea of equal outcomes and emotional harm protection for totemic minorities, represents the ideological endpoint of these sacred values. Like economic socialism, the result of cultural socialism is immiserization and a decline in human flourishing. We must stand against this extremism in favour of moderation.

The woke sanctification of identity did not stem primarily from Marxism, which rejected identity talk as bourgeois, but from a fusion of liberal humanism with the New Left’s identitarian version of socialism. What it produced was a hybrid which is neither Marxism nor classical liberalism.

Left-liberalism is moderate on economics, favouring a mixed capitalism in which regulation and the welfare state ameliorate the excesses of the market, without strangling economic growth. Its suspicion of communist authoritarianism helped insulate it from the lure of Soviet Moscow.

On culture, however, left-liberalism has no guardrails. When it comes to group inequality and harm protection, its claims are open-ended, with institutions and the nation castigated as too male, pale, and stale. For believers, the only way forward is through an unrestricted increase in minority representation. They will not entertain the idea that the distribution of women and minorities across different occupations could reflect cultural or psychological diversity as opposed to “systemic” discrimination. This is the origin of the letters “D” and “E” in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI). Rather than seeking to optimize equity and diversity for maximal human flourishing, these are ends in themselves that brook no limits.

Left-liberals fail to ring-fence the degree of sensitivity that majority groups are supposed to display toward minority groups. Their emphasis on inclusivity through speech suppression rounds out the “I” in DEI. From racial sensitivity training (starting in the 1970s) to the “inclusive” avoidance of words like “Latino” or “mother” that offend and create a so-called hostile environment that silences subaltern groups, majorities are expected to police their speech.

March 30, 2024

QotD: Multiculturalism, in theory and practice

The creed of contemporary multiculturalism sought to establish that all societies were roughly equal and that the “other” was but a crude Western fiction. But we were reminded that people like the Taliban who did not vote, treated women as chattel, and whipped and stoned to death dissenters of their primordial world were different folk from citizens of democracy. A chief corollary to such cultural relativism was that Americans have wrongly embraced a belief in the innate humanity of the West largely out of ethnocentric ignorance. But surely the opposite has been proven true: the more Americans after September 11 learned about the world of the madrassas, the six or seven varieties of Islamic female coverings, the Dickensian Pakistani street, and the murderous gangs in Somalia, Sudan, and Afghanistan, then the more not less, they are appalled by societies that are so anti-Western.

Victor Davis Hanson, Ripples of Battle, 2003.