seangabb

Published 12 Sept 2024Part seven in a series on Everyday Life in the Roman Empire, this lecture discusses demography and life chances during the Imperial period. Here is what it covers:

Introduction – 00:00:00

Our Statistical Civilisation – 00:00:24

Ancient “Statistics” – 00:08:05

How Many Roman Citizens? – 00:18:04

Population of the Empire – 00:21:36

City Populations – 00:27:45

Average Incomes – 00:36:27

Life Expectancy – 00:35:37

Country Life – 00:52:06

Population of Rome – 00:54:39

Feeding Rome – 00:57:40

Roman Water Supply – 01:00:44

Bathing and Sanitation – 01:04:16

Hygienic Value – 01:04:16

Bibliography – 01:06:17

(more…)

March 20, 2025

Everyday Life in the Roman Empire – Demography, Income, Life Expectancy

February 16, 2025

QotD: Why we’re stagnating

I won’t attempt to recap here the many arguments that have been made recently about whether and how our society is stagnating. You could read this book or this book or this book. Or you could look at how economic productivity has stalled since 1971. Or you could puzzle over what else happened in 1971. Or you could read Patrick Collison’s list of how fast things used to happen, or ponder how practically every new movie these days is a sequel, or stare in shock at declines in scientific productivity. This new book by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber starts with a survey of the most damning indicators of stagnation, moves on to suggest some underlying causes, and then suggests an unexpected way out.

Their explanation for our doldrums is simple: we’re more risk averse, and we don’t care as much about the future. Risk aversion means stagnation, because any attempt to make things better involves risk: it could also make things worse, or it could fail and turn out to be a waste of time and money. Trying to invent a crazy new technology is risky, going into consulting or finance is safe. Investing in unproven startups or speculative bets is risky, investing in index funds is safe. Trying to overturn the scientific consensus is risky, keeping your head down and publishing papers that don’t say anything is safe. Producing challenging new art is risky, spewing an endless stream of Marvel superhero capeshit is safe. Even if, in every case, the safe option is the “rational” choice for an individual actor in maximin expected value terms, the sum total of these individually rational choices is a catastrophe for society.

So far this is a lame, almost tautological, explanation. Even if it’s all true, we still haven’t explained why people are so much more fearful of failure than they used to be. In fact, we would naively assume the opposite — society is much richer now, social safety nets much more robust, and in the industrialized world even the very poor needn’t fear starvation. In a very real sense, it’s never been safer to take risks. Failing as a startup founder or academic means you experience slightly lower lifetime earnings,1 while, in the great speculative excursions of the past, failure (and sometimes even success) meant death, scurvy, amputations, destitution, children sold into slavery or raised in poorhouses — basically unbounded personal catastrophe. And yet we do it less and less. Why?

Well, for starters, we aren’t the same people. Biologically, that is. We’re old, and old people tend to be more risk-averse in every way. Old people have more to lose. Old people also have less testosterone in their bloodstream. The population structure of our society has shifted drastically older because we aren’t having any children. This not only increases the relative number (and hence relative power) of older people, it also has direct effects on risk-aversion and future-orientation. People with fewer children have all their eggs in fewer baskets. They counsel those kids to go into safe professions and train them from birth to be organization kids. People with no children at all are disconnected from the far future, reinforcing the natural tendency of the elderly to favor consumption in the here and now over investment in a future they may never get to enjoy.

Old age isn’t the only thing that reduces testosterone levels. So does just living in the 21st century. The declines are broad-based, severe, and mysterious. Very plausibly they are downstream of microplastics and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals. The same chemicals may have feminizing effects beyond declines in serum testosterone. They could also be affecting the birth rate, one of many ways that these explanations all swirl around and flow into one another. Or maybe we don’t even need to invoke old age and microplastics to explain the decline in average testosterone of decisionmakers in our society. Many more of those decisionmakers are women, and women are vastly more risk-averse on average.2

John Psmith, “REVIEW: Boom, by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2024-11-11.

1. And given the logarithmic hedonic utility of additional money and fame, that hurts even less than it sounds like it would.

2. If you’re too lazy to read Jane’s review of Bronze Age Mindset but just want the evidence that women are more cautious and consensus-seeking than men on average, try this and this and this for starters.

February 9, 2025

A “certain niche Canadian’s” prophetic look at Western demography

Mark Steyn reminds us that it’s twenty years since he published America Alone: The End of the World as We Know It, which has become more and more accurate every year:

~As some readers may be aware, next year marks the twentieth anniversary of a certain “niche Canadian”‘s boffo international bestseller on demography. So the other day I was musing on whether it was too soon to mark the occasion — only to find I’d been beaten to the punch by the Nigerian media bigfoot Azu Ishiekwene:

It’s nearly 20 years since Mark Steyn wrote a non-fiction book, America Alone: The End of the World as We Know It.

Steyn, a Canadian newspaper columnist, could not have known that the kicker of this book title, which extolled America as the last bastion of civilisation as we know it, would become the metaphor for a wrecking ball.

Steyn thought demographic shifts, cultural decline, and Islam would ruin Western civilisation. The only redeeming grace was American exceptionalism. Nineteen years after his book, America Alone is remembered not for the threats Steyn feared or the grace of American exceptionalism but for an erratic president almost alone in his insanity.

The joke is on Steyn.

Oh, well. It was good while it lasted — which wasn’t as long as it should have, thanks to the dirty stinkin’ rotten corrupt American “justice” system (see below).

~But I thank Mr Ishiekwene for reminding me of the twin theses of my book: on the one hand, “demographic shifts, cultural decline, and Islam” and, on the other, “American exceptionalism”. The first half is undeniable: At one point last year, there were no Anglo-Celtic heads of government anywhere in the British Isles except for Northern Ireland. Nobody even talks about “demographic shifts”, with even “conservative” politicians preferring to focus on “British values” or “French values” or “[Your Country Here] values”, even as those “values”, not least freedom of speech, are remorselessly surrendered. The UK’s “Deputy Prime Minister”, Angela Rayner, is proposing as the state’s reaction to the Southport stabbings, about which the most intemperate Tweeters were less inaccurate than the state propaganda, to restrict free expression even further. Islam? In Britain, Germany, France, the Netherlands, we would rather our children be stabbed and gang-raped than do anything about it, especially if it risks being damned as “Islamophobic”. The delightful Ms Rayner, who once boasted about flashing her soi-disant “ginger growler” across the Commons to Boris Johnson at Question Time, will be keeping it under wraps in the years ahead.

~As for the second part of my book’s arguments — “American exceptionalism” — well, it’s been a rough twenty years. But, to cast Azu Mr Ishiekwene’s contempt for an “an erratic president almost alone in his insanity” in a more generous light, the last three weeks have been a useful reminder that America is still different — or, at any rate, retains the capacity to be different. In his first days in office Trump 47 yanked the US from the World “Health” Organisation and the Paris “climate” accord and the UN “Human Rights” Council. If I have been insufficient in my praise for this energy, it is only because I held out hopes that a man “alone in his insanity” might have simply nuked the WHO. But, such disappointments aside, in Britain (and in the EU it has yet to leave in any meaningful sense), no such decisive acts in the here-and-now can even be contemplated.

And just because I’ve been including a fair bit of USAID-related stuff this week, he comments on Elon Musk’s epic sidequests investigations into US government waste and corruption:

~That’s the good news — and it’s very heartening. The bad news is that almost everything the national government (it is no longer really “federal”) of the United States touches is a racket.

The United States Agency for International Development is so-called in order that gullible rubes who listen to NPR think that it’s something to do with helping starving children in Africa. The cynical rubes who follow Conservative Inc think it’s something to do with helping African dictators’ Swiss bank accounts and endlessly regurgitate the old line about “international aid” taking money from poor people in rich countries to give to rich people in poor countries. But this is the cynicism of the terminally naïve and does a great injustice to the average blood-drenched Somali warlord. As Elon Musk has pointed out, ninety per cent of USAid funds are disbursed in the Washington, DC area. Opponents of that line say, ah, yes, but that’s misleading because some of it then gets passed on outside the Beltway eventually to reach some emaciated Congolese laddie.

Well, I would doubt it. There is no legitimate reason for Bill Kristol and Mona Charen to be receiving any funds from an agency for “international development” — and they surely know it. The least we should expect from them is that they come by their Never Trumpery honestly.

But I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that that 90-10 ratio is pretty standard. The US armed forces account for forty per cent of the planet’s total military spending. Does ninety per cent of that also get disbursed in the District of Columbia? On Thoroughly Modern Milley’s ribbon budget? It’s as good an explanation as any for the failure to win anything since VJ Day. The rube right’s antipathy to foreigners shouldn’t blind us to the fact that the overwhelming majority of the corruption is domestic — and it’s a very bipartisan sewer.

So I wish Trump, Musk et al the best of luck. But, notwithstanding that every rinky-dink District Court judge seems to be labouring under the misapprehension that he’s head of the executive branch of government, Trump has spent the last three weeks doing things. There is no sign that that is even possible in the rest of the west, where the Dutch model seems to prevail: Geert Wilders wins the election, but then gets neutered.

So, in a sense, Azu Ishiekwene is right. There is a yawning chasm between Trump and the poseur attitude-flaunting rest of the west. And yet Mr Ishiekwene is wrong on this: an erratic president is not almost alone in his insanity. In case you haven’t noticed, Panama won’t be renewing its Chinese deal on the Belt & Road Initiative, and El Salvador is happy to gaol anybody Trump sends them. It turns out that the quickest way to solve any international dispute is to threaten the recalcitrant with twenty-five per cent tariffs starting at midnight. If the forty-seventh president doesn’t seem interested in “winning hearts and minds”, it’s because he’s found something more effective.

January 31, 2025

Canada – sovereign nation or “post-national state” with “no core identity”?

In The Line, Andrew Potter retraces Canada’s history from British colony to self-governing Dominion to proud mover-and-shaker in the postwar world to whatever the heck it is today:

There is a map that shows up on social media from time to time, and it looks like this.

Sometimes it is followed by this one:

And then maybe this one:

What’s the point of these maps? Apart from noting the obvious, which is that Canada is sparsely populated, and much of the population is gathered in cities very close to the border with the United States, they raise important questions about the exercise of political power and its legitimacy, forms of governance, and, ultimately, sovereignty. By what methods did Canada come to be, and by what right does a small and relatively concentrated group of people, most of whom live down by the Great Lakes or along the St. Lawrence River, lay claim to almost ten million square kilometres of the Earth’s landmass?

It is easy to draw lines on maps. Anyone can do it. If you want those lines to represent some sort of generally accepted reality, two things must be true. First, the people inside the lines need to see those lines as legitimate, and be willing to take the necessary steps, up to and including the use of force, to assert them against outsiders. And second, enough outsiders of sufficient global importance also need to recognize those lines.

Any student of Canadian history knows that the borders of Canada are highly contingent. Rewind the tape of the past, and there are any number of moments where things could have turned out differently. In some scenarios, Canada ends up smaller than it currently is; in others, Canada ends up larger, perhaps substantially so. And in some alternative histories, Canada does not exist at all — or if it does, we’re all speaking French.

There’s nothing that is either sinister or celebratory in pointing this out. History is a bunch of stuff that happened, and in some cases, things might have turned out differently. But again, if you know your Canadian history, you know that the process by which Canada went from a French fur trading outpost to a collection of British mercantile colonies to a continent-spanning multinational federation and parliamentary democracy was made possible only through a rough admixture of ambition, cunning, scheming, coercion, violence, strong foreign support, and, between 1812 and 1814, war.

To get to the point: Canada’s sovereignty wasn’t something we just stumbled upon, nor is it something we were happily given. It was a thing we did. We did not do it alone, though; for most of the 19th century, the main ongoing threat to Canada’s sovereignty was the United States, while the ultimate guarantor of that sovereignty was Great Britain.

That dynamic shifted over the first half of the 20th century, when the British Empire went into decline, and the United States became the dominant world power. There was a short period after 1931, while British influence was ebbing and that of the Americans was flowing, in which Canada stood more or less independent and autonomous. This largely ended in 1940; Britain was on the ropes against Nazi Germany, Canada was in Hitler’s sights, and an increasingly anxious Franklin Roosevelt invited Mackenzie King down to Ogdensburg, New York, for a friendly chat about continental security.

December 11, 2024

Canada’s current situation, as viewed by Fortissax

Fortissax recently spoke to an audience in Toronto. This is part of the transcript of his speech:

No doubt, many of you already have an idea.

The fact of the matter is this: 25% of the people in this country are, or soon will be, foreigners. Most of them are not the children of immigrants but fresh-off-the-boat migrants.

The economy? It’s in the dumps. Canada has the lowest upward mobility in the OECD for young people. One of the lowest fertility rates in the Western world. And the fastest-changing demographics in the Western world — as I’m sure you’ve all noticed here in the streets of Toronto, the old capital of Anglo-Canadians.

Think about this: approximately 4.9 million foreigners are classified as “temporary migrants.” Combine that with permanent residents, refugees, and immigrants, and that number swells to 6.2 million in just four years.

And it doesn’t stop there.

Crime is reportedly the highest it’s ever been. We have no military. The Canadian Armed Forces has faced retention issues for two decades. And what is command preoccupied with? Men’s bathrooms stocked with tampons and servicemen being “radicalized” by wearing extremist clothing like MAGA hats.

Let’s not forget foreign influence.

The Chinese Communist Party exploited the Hong Kong handover in the 1990s to infiltrate Canada, using British Columbia as their foothold. As Sam Cooper exposes in Claws of the Panda and Willful Blindness, they established a stronghold in Metro Vancouver, taking over the business community.

This “Vancouver Model”, as we Canadians ironically call it, normalizes our capitulation to foreign hostiles. Triads, working hand-in-glove with the Chinese communists, built a global drug empire. Fentanyl, mass-produced in football field-sized factories in China, is shipped to Vancouver and distributed across the entire Western Hemisphere.

Let this sink in: more Canadians have died from this economic warfare than all our soldiers lost in the Second World War.

And now, there’s India.

Intelligence agencies from the Republic of India have demonstrated their ability to conduct assassinations on Canadian soil. Recently, a Khalistani nationalist and separatist was killed — a figure I’ll leave to your sympathies or judgments. Regardless, this marks a disturbing shift.

India weaponizes its diaspora against the international community. In exchange for non-alignment with China, the West — particularly the Anglosphere — uses Indian migrants as wage-slave labor to suppress costs.

The result? A disaster.

In Canada, Australia, the U.K., and increasingly the United States, we see Indians climbing the ladders of power, pursuing their own interests — often brazenly. In Brampton, part of Greater Toronto, a 50-foot statue of the Hindu god Hanuman looms.

And let’s not forget the Punjabi Sikh population. They openly support an independent Khalistan — or remain at best indifferent to the cause. They have infiltrated Canada’s state apparatus, even reaching the Ministry of National Defense, where Harjit Sajjan prioritized rescuing Afghan Sikhs during Kabul operations over broader Canadian interests.

In Surrey, British Columbia, the trucking industry is effectively controlled by Sikhs. In online spaces, Sikh nationalists demand Brampton be recognized as a province, seemingly aware that their homeland exists more abroad than in Punjab itself. The leader of the NDP, Jagmeet Singh, serves as yet another example — barred from entering India due to his sympathies for separatism.

But foreign influence is only half the story. Among our own lies another problem: disintegration.

Decades of Western alienation and economic parasitism by the federal government are fueling separatist movements in places like Alberta and Saskatchewan. In Quebec, the Parti Québécois is polling higher than the ruling CAQ, openly advocating for secession from Confederation.

Meanwhile, the federal Conservatives court immigrant voters, alienating native Canadians and abandoning their base.

And then there’s the economic misery.

The average Canadian home costs $700,000. The median income? Just $48,000. Upward mobility is nonexistent. The managerial regime hoards wealth and power, gatekeeping opportunity through credentialism, exorbitant tuition, and crushing taxes.

55% of Canadians have post-secondary education, and yet most have nothing to show for it. The regime is not run by titans of intelligence or visionaries. It’s run by ideologues — loyal to their cause, not to competence or merit.

The final insult: demographics.

Over the next six years, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba will become majority non-Canadian. The 50% threshold will be breached, with profound consequences for local politics.

Ontario will hover just above 50%, while Quebec and the Maritime provinces will remain over 70% and 80% Canadian, respectively. This is not a death sentence, but it is a profound transformation for Western Canada, which has historically been more propositional and less identitarian than the East.

This is where we are.

Our sovereignty is compromised. Our identity is eroded. But we are not yet defeated. What happens next depends entirely on us.

November 10, 2024

Post-election thoughts from Andrew Sullivan

Given how … anguished … Andrew Sullivan seemed to be during the run-up to voting day, he’s either calmed down dramatically or he’s renounced the over-the-top hysterics for the moment:

You can always spot a fool, for he is the man who will tell you he knows who is going to win an election. But an election is a living thing — you might almost say, the most vigorously alive thing there is — with thousands upon thousands of brains and limbs and eyes and thoughts and desires, and it will wriggle and turn and run off in directions no one ever predicted, sometimes just for the joy of proving the wiseacres wrong

Robert Harris in his novel Imperium (2006).This last decade or so, we’ve heard an awful lot about the new fragility of American democracy. So it bears noting that, after much angst, we somehow pulled this election off. Kudos to the election workers. Kudos to the voters for providing a clear and decisive result. Kudos to Harris for the graceful concession (in stark contrast to Trump in 2020). We have not lurched into another crisis of democratic legitimacy. No windows are being smashed; no statues are being torn down.

And there is, yes, a mandate. When one party wins the presidency, Senate, and probably the House, that’s usually the case. But this year, the policy divides were particularly clear, and the shift so clear and in one direction everywhere. Americans have voted for much tighter control of immigration, fewer wars, more protectionism, lower taxes, and an emphatic repudiation of identity politics. In the immortal words of Mencken: “Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.” We’ll soon see how that pans out.

But the good news is that we have become less tribal. The president whom Ta-Nehisi Coates derided as whiteness personified just won more non-white votes than any Republican since Nixon. The allegedly xenophobic campaigner against illegal immigration gained massively among various Spanish-speaking constituencies and many legal immigrants, especially men. The champion of rural whites somehow also made his biggest electoral gains in the big, non-white cities, and among Hispanic voters in Texas border counties. A Republican whom the left and the legacy media called a “white supremacist” won about 24 percent of the black male vote and 47 percent of the Latino male vote.

What about the huge impact of enraged women we were told about, especially in the wake of the Selzer poll in Iowa? Again: a nothingburger. Biden won women by 12 points; Harris — a woman candidate after the end of Roe — won by only 7 points. Ruy Teixeira runs through the other demos here. Gen Z? Biden won women under 30 by 32 points, and Harris by a mere 18. Meanwhile, men under 30 went from +15 for Biden to +14 for Trump — a truly staggering swing! Trump gained among Jews and Muslims! Harris was the candidate of the Upper West Side. The Bronx moved massively to Trump.

How could an entire left-liberal worldview be more comprehensibly dismantled by reality? And yet, the primary response among my own liberal friends was rage at the electorate. They texted me to insist that Harris lost because of white people — white women, in particular, their favorite bêtes blanches. The NYT’s resident race-baiter, Nikole Hannah-Jones, made her usual point:

Since this nation’s inception large swaths of white Americans — including white women — have claimed a belief in democracy while actually enforcing a white ethnocracy.

In fact, among the few demos where Harris did better than Biden were white people earning over $100,000 a year, white women, white men, and “LGBT” voters — most of whom are now young, bi, white women in straight relationships. Warming to her racism, NHJ went after “the anti-Blackness … in Latino cultures as well.” Here’s how Joan Walsh put it:

[Biden]’s got a couple things that my girl Kamala didn’t have. A penis, and that nice white skin.

But more whites went for Kamala than Biden! If you want proof that critical race, gender and queer theory is unfalsifiable, you just got it. The Dems and most of the legacy media have literally no frame of reference outside “white-bad/black-and-brown-good” and “men-bad/women-good”.

And no, Harris did not run a “flawless campaign“. Please. She ran one with no coherent message. She picked a woke weirdo as veep. She embraced neocons like Liz Cheney while never breaking decisively with Biden or the left. She had no credible answers on immigration and inflation. She had nothing coherent to say on foreign policy. She thought Cardi B and Stephen Colbert were arguments.

On Trump as a potential dictator, Americans keep telling us they don’t really buy it. They may be wrong … and maybe they are. But if you are going to respect democracy, you also need to respect their judgment, and honor their choice. I suspect they think he will throw his weight around, but will be constrained as he was last time around by the ability of the American system to stymie most radical moves. But they want him to end mass illegal immigration, and I suspect they will give him some leeway to get there. The Dems had their chance to enforce the border and instead chose to open the floodgates. What Trump now does is therefore their responsibility too.

October 7, 2024

The demographic impact of modern cities

Lorenzo Warby touches on some of the social and demographic issues that David Friedman discussed the other day:

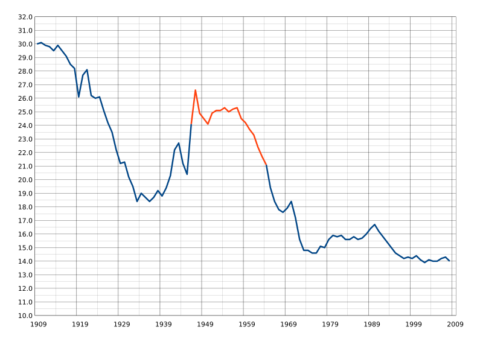

US Birth Rates from 1909-2008. The number of births per thousand people in the United States. The red segment is known as the Baby Boomer period. The drop in 1970 is due to excluding births to non-residents.

Graph by Saiarcot895 via Wikimedia Commons

Cities are demographic sinks. That is, cities have higher death rates than fertility rates.

For much of human history, cities have been unhealthy places to live. This is no longer true: cities have higher average life expectancies than rural areas. But they are still demographic sinks, for cities collapse fertility rates.

The problem is not that more women have no children, or only one child, making it to adulthood. Such women have always existed, though their share of the population has gone up across recent decades.

The key problem is the collapse in the demographic “tail” of large families. Cities are profoundly antipathetic to large families, and have always been so. This is particularly true of apartment cities — suburbs are somewhat more amenable to large families, though not enough to make up for the urbanisation effect.

While modern cities do not have slaves and household servants who were blocked from reproducing as ancient cities did, various aspects of modern technology have fertility-suppressing effects. Cars that presume a maximum of three children, for instance. An effect that is worsened by compulsory baby car-seats. Or ticketing and accommodation that presumes two children or less. There is also the deep problems of modern online dating. Plus the effects that endocrine disrupters and falling testosterone may be having.

These effects also extend to rural populations: falling fertility in rural populations is far more of a mystery than falling fertility in urban populations. How much declining metabolic health plays in all this is unclear. Indeed, futurist Samo Burja is correct, we do not really understand the “social technology” of human breeding.

Be that as it may, cities as demographic sinks is a continuation of patterns that go back to the first cities.

Matters at the margin

There are factors at the margin known to make a difference. Religious folk breed more than secular folk, though that is in part because rural people are more religious and city folk more secular.

Educating women reduces fertility. This is, in part, an urbanisation effect, as more education is available in cities. It is also an opportunity cost effect — there is more to do in cities, both paid and unpaid.

Education increases the general opportunity cost of motherhood, by expanding women’s opportunities. This also makes moving to cities more attractive. Women having more career opportunities reduces the relative attractiveness of men as marriage partners, reducing the marriage rate.

Strong cultural barriers against children outside marriage can reduce the fertility rate, by largely restricting motherhood to married women. This makes the fertility rate more dependant on the marriage rate.

Educating women makes children more expensive, as educated mothers have educated children. Part of the patterns that economist Gary Becker analysed.

October 5, 2024

David Friedman on falling birth rates

In the west, generally speaking, female employment and economic power has been rising and birth rates have been falling, except among religious minorities. David Friedman provides some explanations:

“Tetra Pak® – Housewife at the dairy counter in a Swedish shop” by Tetra Pak is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

One possible explanation is changes in norms and legal rules that make mate search more difficult. An example is a norm against dating fellow employees and a stronger norm against dating someone who has authority over you or you have some authority over.

For many people, their job is the only context in which they routinely interact with lots of other people, the best environment for mate search. The interaction often provides a way of evaluating someone for characteristics such as honesty and competence as well as compatibility, much harder to do in the context of dating, harder still in computer dating. It works better for people who not only are fellow employees but are actually working together, which often means one just above the other in the office hierarchy.

The same issue arises in the university context. Undergraduates are free to date each other — mate search is arguably one of the main functions of college. Junior faculty members, likely to be unmarried, are commonly not supposed to date students, even students not taking classes from them, certainly not students who are. I am not sure what current norms are for graduate student/undergraduate interaction, expect graduate student/faculty romance to be at least somewhat frowned upon, especially if the faculty member has some authority over the student which is likely if they are in the same field, the context in which they are most likely to get know each other.

Another cause for declining birth rates might be changing norms of courtship. I have not been part of that market for over forty years but I gather from what younger people say online that many men believe that making advances that do not turn out to be wanted is not only embarrassing but dangerous, that they risk being accused of harassment or some related offense. In the student context, many men believe that if a romantic partner changes her mind she can get him into a great deal of trouble by taking advantage of a college disciplinary process heavily biased against men. I do not know to what degree that belief is true but many men believe it is, which could be expected to discourage courtship.

Along related lines:

Also, when I was working for a big time international consulting firm, they tried to come out with a formal rule that said that you were allowed to ask out a co-worker, but only one time. If they said no, you could never ask again. Apparently the Italians howled with laughter and insisted that if this rule was enforced in Italy, no one would ever have kids, as the typical Italian courtship approach involves like a dozen rejections before ultimately the woman finally gives in. (GoneAnon)

That cannot be the full explanation since Italian birth rates are down too. Since birth rates are down in all or almost all developed countries and many less developed ones, it is worth investigating how widespread the relevant norms are.

Housewife Becoming a Low Status Profession

For a very long time, the default system for producing and rearing children was a married couple, with the husband producing income and the wife in charge of running the household and rearing the children. Over recent decades, the woman’s role in that division of labor has become a low status activity, lower status than making a living in the marketplace, much lower than professional success.1 Being an unmarried adult woman used to be, in most contexts, low status, on the presumption that if she could have caught a man she would have. At present, in much of western society, that has reversed — being a married housewife is lower status than being an employed single woman.

…arguments from the stay-at-home moms I know, who say people are constantly giving them grief about it, and who are often looking for some part-time make-work job they can take just so people will stop giving them grief about being a stay-at-home mother (Scott Alexander)

It is possible for a married woman to have both a job and children or for an unmarried woman to have children, but the former is more difficult than for a full time housewife, the latter much more difficult.

1. For a much more detailed presentation of this explanation, along with arguments against a variety of alternatives, see It’s embarrassing to be a stay-at-home mom.

August 19, 2024

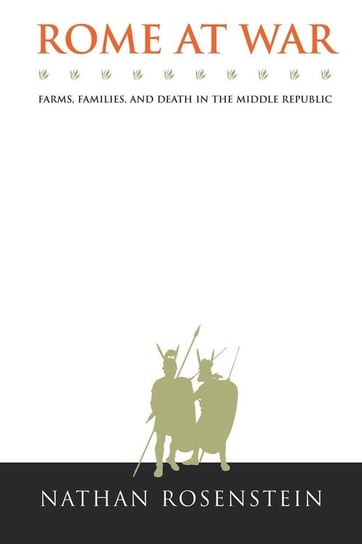

Bret Devereaux on Nathan Rosenstein’s Rome at War (2004)

Although Dr. Devereaux is taking a bit of time away from the more typical blogging topics he usually covers on A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, he still discusses books related to his area of specialty:

For this week’s book recommendation, I want to recommend N. Rosenstein, Rome at War: Farms, Families and Death in the Middle Republic (2004). This is something of a variation from my normal recommendations, so I want to lead with a necessary caveat: this book is not a light or easy read. It was written for specialists and expects the reader to do some work to fully understand its arguments. That said, it isn’t written in impenetrable “academese” – indeed, the ideas here are very concrete, dealing with food production, family formation, mortality and military service. But they’re also fairly technical and Rosenstein doesn’t always stop to recap what he has said and draw fully the conclusions he has reached and so a bit of that work is left to the reader.

That said, this is probably in the top ten or so books that have shaped me as a scholar and influenced my own thinking – as attentive readers can no doubt recall seeing this book show up a lot in my footnotes and citations. And much like another book I’ve recommended, Landers, The Field and the Forge: Population, Production and Power in the Pre-Industrial West (2003), this is the sort of book that moves you beyond the generalizations about ancient societies you might get in a more general treatment (“low productivity, high mortality, youth-shifted age profile, etc.”) down to the actual evidence and methods we have to estimate and understand that.

Fundamentally, Rome at War is an exercise in “modeling” – creating (fairly simple) statistical models to simulate things for which we do not have vast amounts of hard data, but for which we can more or less estimate. For instance, we do not have the complete financial records for a statistically significant sample of Roman small farmers; indeed, we do not have such for any Roman small farmers. So instead, Rosenstein begins with some evidence-informed estimates about typical family size and construction and combines them with some equally evidence-informed estimates about the productivity of ancient farms and their size and then “simulates” that household. That sort of approach informs the entire book.

Fundamentally, Rosenstein is seeking to examine the causes of a key Roman political event: the agrarian land-reform program of Tiberius Gracchus in 133, but the road he takes getting there is equally interesting. He begins by demonstrating that based on what we know the issue with the structure of agriculture in Roman Italy was not, strictly speaking “low productivity” so much as inefficient labor allocation (a note you will have seen me come back to a lot): farms too small for the families – as units of labor – which farmed them. That is a very interesting observation generally, but his point in reaching it is to show that this is why Roman can conscript these fellows so aggressively: this is mostly surplus labor so pulling it out of the countryside does not undermine these households (usually). But that pulls a major pillar – that heavy Roman conscription undermined small freeholders in Italy in the Second Century – out of the traditional reading of the land reforms.

Instead, Rosenstein then moves on to modeling Roman military mortality, arguing that, based on what we know, the real problem is that Rome spends the second century winning a lot. As a result, lots of young men who normally might have died in war – certainly in the massive wars of the third century (Pyrrhic and Punic) – survived their military service, but remained surplus to the labor needs of the countryside and thus a strain on their small households. These fellows then started to accumulate. Meanwhile, the nature of the Roman census (self-reported on the honor system) and late second century Roman military service (often unprofitable and dangerous in Spain, but not with the sort of massive armies of the previous centuries which might cause demographically significant losses) meant that more Romans might have been dodging the draft by under-reporting in the census. Which leads to his conclusion: when Tiberius Gracchus looks out, he sees both large numbers of landless Romans accumulating in Rome (and angry) and also falling census rolls for the Roman smallholder class and assumes that the Roman peasantry is being economically devastated by expanding slave estates and his solution is land reform. But what is actually happening is population growth combined with falling census registration, which in turn explains why the land reform program doesn’t produce nearly as much change as you’d expect, despite being more or less implemented.

Those conclusions remain both important and contested. What I think will be more valuable for most readers is instead the path Rosenstein takes to reach them, which walks through so much of the nuts-and-bolts of Roman life: marriage patterns, childbearing patterns, agricultural productivity, military service rates, mortality rates and so on. These are, invariably, estimates built on estimates of estimates and so exist with fairly large “error bars” and uncertainty, but they are, for the most part, the best the evidence will support and serve to put meat on the bones of those standard generalizing descriptions of ancient society.

June 16, 2024

“What the hell is going on in Canada?”

If you’re not Canadian or have any Canadian friends, you may not understand just how badly broken the country is — and the federal government is still desperately pretending that we’re all onboard with the Net Zero/Carbon Tax/”you’ll own nothing” bullshit and piling on the long-term debt:

One of Canada’s intelligence agencies, a couple of months ago, sent a memo to the Liberal federal government informing them that, in the near-future years to come, they are worried about revolutionary activity. I believe Canada is a good case study because it seems the country has been a sociological testing ground for the powers that be to see what happens. Canada is a surreal twilight zone where it feels like every psyop known to man is hurled its way. Canada unquestionably has the worst demographic and immigration issues, the worst housing issues, the worst social stability, and upwards mobility issues, all adjusted and proportional to its population and size, of course. For our purposes, I believe Canada serves as the worst-case scenario of how bad the dating market can be, and how bad it will continue to get.

Canada has some of the lowest upward social mobility among developed nations, especially for young people, particularly within the OECD and G8. This means that young people in Canada find it relatively difficult to move up the economic ladder compared to their parents.

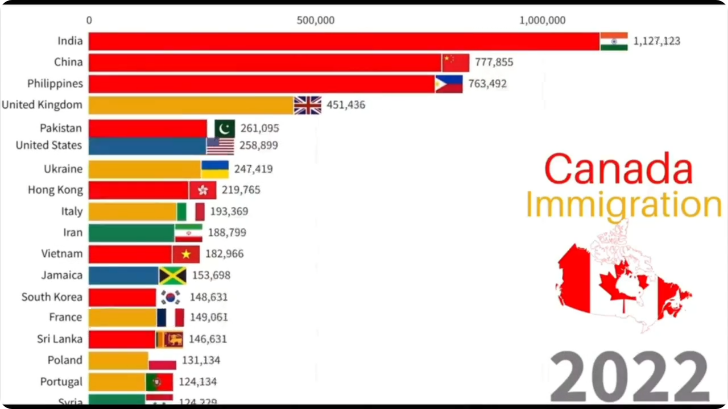

In 2022, Canada’s population growth was significantly driven by immigration. According to Statistics Canada, approximately 95% of the population growth in that year was attributed to immigration. This includes both permanent and temporary residents, with a notable influx of international students, temporary workers, and permanent residents. Only a meagre 5% of Canada’s population growth, including recent immigrants, was from organic growth and childbirth. Below are the national origins of immigrants over the last twenty-four years. The combined total number of people entering Canada per year, including international students, temporary foreign workers, legal immigrants, and refugee claimants, is approximately 1,133,770 individuals officially. In reality, the government over the last four years has lost count.

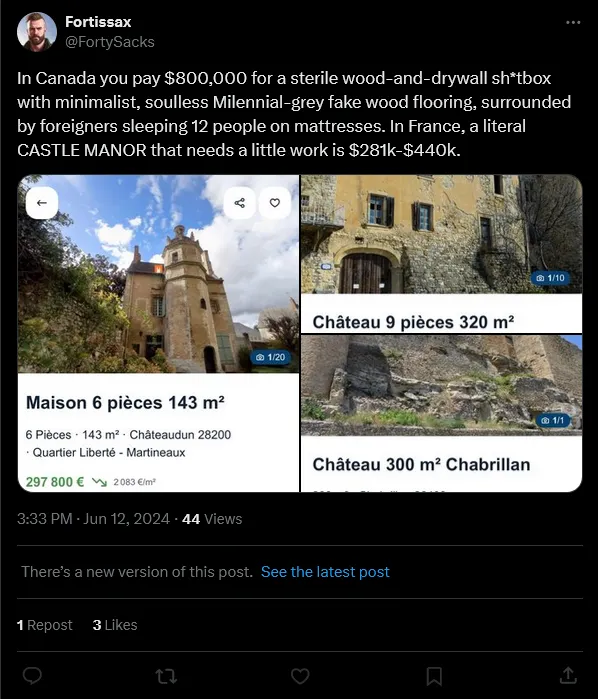

As of April 2024, the average home price in Canada is approximately CAD $703,446. This is €477,121.93 and USD $511,466.93. Would you like to see what $703k CAD can get you in France? Hint: a lot more than in Canada.

This has been noticed so much by Canadians that it is now a meme, with Conservative Party and opposition leader Pierre Poilievre pointing it out in the House of Commons. You can compare the price of homes and the cost of living with Canadian wages. You can also compare how far those meagre wages would go in other first-world countries like France, Germany, or Sweden. The answer is much farther. Much, much farther. There is currently no hope, short of radical action by the government unheard of in Canadian history, for this situation to be rectified. The only other option is best left unsaid.

“Educated” Women Lead

In Canada, among ethnic Canadians, a significant portion of the female population is more educated and makes more money than Canadian men. Canadian men make, on average, CAD $48,500, while women make CAD $42,000. However, only 56% of men have post-secondary education, while 68% of women do. Men have completed higher levels of high school, and women have completed higher levels of college or university. This has led to a massive gap in socioeconomic status between men and women. It gets worse when you include non-ethnic Canadians. Completed levels of post-secondary education for men remain at 56%, while women’s rise to 73%.

We know that in our post-industrial world, resources translate to money. Money and completed levels of education translate to status. Women are 50% more likely to divorce men when they make more money. When women are already the initiators of divorce 70% of the time, it starts looking pretty ugly, fast.

June 11, 2024

Mark Steyn on Nigel Farage

This is from his Friday round-up post at SteynOnline:

“Nigel Farage” by Michael Vadon is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

Demography is relentless. Douglas Murray notes that the BBC is always warning that the “far right” is “on the march“, but in the west it is demographic transformation that is truly on the march, quietly and unreported, picking up pace every month. By comparison, the wretched Sunak/Starmer dinner-theatre of the UK election campaign is completely irrelevant to Britain’s future. So I am glad to see that Nigel Farage has had a change of heart and opted to join the battle. Back in 2016, in the days after the Brexit vote, I said he was the most consequential figure in UK politics since Mrs Thatcher. Which was true. Alas, people most Britons have never heard of then set about subverting Brexit, and very effectively.

So here we are eight years later, with half-a-million Anglo-Celts abandoning the UK each year and a million Pushtun warlords and Sudanese clitoridectomists and Albanian sex-traffickers taking their place. Demography is relentless, and the hour is late.

Over a decade ago — in fact, closer to two, as I estimate it — Nigel Farage said to me that the first thing you have to do when you found a new political party on the right is to accept the burden of being its only member — at least for a while. Because the first 10,000 people who want to join are neo-Nazis and skinheads and the like. It was a clever insight, and he spread it around. So I had it told back to me many times over the years by populist politicians from all over the Continent, Danes and Dutch, Swedes and Spaniards alike.

Nigel took his gatekeeping seriously — and not just on the domestic front, “distancing” himself from Tommy Robinson and Tommy-associated issues such as Islam and the industrial-scale sex-slavery of thousands of English girls. As Gavin Mortimer reminds us, a decade ago Farage also rejected any Euro-collaboration with Marine Le Pen because her party had “anti-Semitism and general prejudice in its DNA“. Geert Wilders (for whose fine book I am proud to have written the introduction) was furious with Farage and attempted to broker a rapprochement. Nigel was having none of it.

So here we are a decade later:

* in the Netherlands, Wilders is currently the most powerful politician, leading the most popular party, and has helped move the electorate significantly;

* in France, Mme Le Pen’s party will, in just two days’ time, win the European elections. She is the de facto leader of the opposition, and her caucus in the National Assembly is the largest and most effective opponent to Macron. She has also helped move the electorate significantly;

* in the United Kingdom, by contrast, voters are about to elect a left-wing government led by a fellow, Sir Vics Starmer, who thinks men can have a cervix.

I think Nigel over-gatekept.

He has been very good at founding personal vehicles (Ukip, the Brexit Party) that deflate like punctured soufflés when he steps down as leader. Yes, he was very watchable in the jungle on “I’m a Celebrity — Get Me Out of Here”, and, in my GB News days, he certainly handed me a bigger audience at 8pm than any of his guest-hosts. But, as that station’s currently Farageless ratings reveal, you can’t build a sustained movement on one man. Nigel’s advice was clever twenty years ago. Wilders, LePen, Meloni et al were wise to recognise its limitations.

So I’m pleased Farage changed his mind on this election. He should change his mind on the over-gatekeeping, too.

Time and demography march on.

May 20, 2024

At what point did “quiet genocide” become the preferred option for the climate cultists to “save the planet”?

The Daily Sceptic‘s Chris Morrison on the not-so-subtle change in the opinions of the extreme climatistas that getting rid of the majority of the human race is now the preferred way to address their concerns:

The grisly streak of neo-Malthusianism that runs through the green movement reared its ugly head earlier this week when former United Nations contributing author and retired UCL Professor Bill McGuire tweeted that the only “realistic way” to avoid catastrophic climate breakdown was to cull the human population with a high fatality pandemic. The tweet was subsequently withdrawn by McGuire, “not because I regret it”, but people took it the wrong way. McGuire is the alarmists’ alarmist, suggesting for instance that human-caused climate change could lead to more earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The Daily Sceptic will not take his views the wrong way. They are an illuminating insight into environmental Malthusianism that does not get anything like the amount of publicity it deserves.

Every now and then Sir David Attenborough allows the genial TV presenter mask to slip to reveal a harder-edged Malthusian side. Speaking to BBC Breakfast in 2021, he suggested that the Earth would be better off without the human race, describing us as “intruders”. In 2009, Attenborough became the patron of the Optimum Population Trust and told the Guardian: “I’ve never seen a problem that wouldn’t be easier to solve with fewer people.” In 2013, he made the appalling remark that it was “barmy” for the United Nations to send bags of flour to famine-stricken Ethiopia. Too little land, too many people, was his considered judgement.

Any consideration of the refusal of food aid these days brings to mind the 19th century Malthusian Sir Charles Trevelyan, the British civil servant during the Irish famines who saw the starvation as retribution on the local population for their moral failings and tendency to have numerous children. He is said to have seen the great loss of life as a regrettable but unavoidable consequence of reform and regeneration.

Anti-human sentiment is riven through much green thinking. In 2019, Anglia Ruskin University Professor Patricia MacCormack wrote a book suggesting humans were already enslaved to the point of “zombiedom” because of capitalism, and “phasing out reproduction is the only way to repair the damage done to the world”. Green fanatics can be a joyless crowd – it is not enough to declare a climate crisis, now they want a “nookie” emergency. As the economist and philosopher Robert Boulding once remarked: “Is there any more single-minded, simple pleasure than viewing with alarm? At times it is even better than sex.”

May 17, 2024

“Once a mind is infected with Climate Change, bioweapons are just another kind of carbon credit”

Jo Nova presents evidence of a university professor — a vulcanologist — who perhaps has more sympathy for the volcanoes he studies than the human race:

Let’s just say, hypothetically, that someone wanted an excuse to reduce global population, or limit competing tribes and religions, there’s a scientific hat for that. Climate Change is the ultimate excuse for mass death — done in the nicest possible way and for the most honorable of reasons. But isn’t that what they all say: Jim Jones, the Branch Davidians, Heavens Gate — death makes the world a better place?

The cult that pretends it isn’t a cult sells itself as “science”. I mean, what the worst thing you can think of? Would that be one degree of warming, or the Black Death?

In Bill McQuire’s mind the catastrophe is not when billions of innocent people die.

One hundred years from now, what would our great grandchildren prefer: that the world was slightly cooler or they were never born at all? If you hate humans it’s a terrible dilemma …

Bill McGuire, vulcanologist, accidentally put his primal instincts in a tweet last weekend:

Thirty years of telling us that humans are bad has consequences. As Elon Musk said” They want a holocaust for humanity.” It turns out a televised diet of one-sided climate projection by mendicant B-Grade witchdoctors might be a dangerous thing for mental health. If only Bill McQuire had seen a skeptic on TV?

Predictably the McGuire tweet spread far, and got crushing replies so the Emeritus Professor deleted it, as all cowards do, yelling at us:

May 10, 2024

A different take on the Russo-Ukrainian War

Kulak suggests that far from being a model for future wars, the ongoing conflict in Ukraine may not prefigure anything at all about future wars:

Few weeks go by where I don’t read a piece on how Ukraine is the Future of warfare and armies and thinkers need to adjust to the reality that the warfare of the future will involve massive unaccountable amounts of artillery, trenches, conscription and grinding warfare.

While sometimes they point to relevant lessons: Yes the inability of the US to quickly reindustrialize and produce artillery shells at a rate comparable to Russia does speak to a profound rot in American governance, the military industrial complex, and American business regulation more generally,

Often times the conclusions drawn are dangerously delusional: A draft would be more likely to break the American nation than save it. As indeed conscription has resulted in Ukraine’s population collapsing with somewhere between 6 and 10 million Ukrainians (out of a pre-war 36 million) having fled the country, not to escape the mostly static war, but to escape the Totalitarian conditions the Zelensky regime has imposed in response to the war. (1.1 million of whom escaped INTO Russia, for any who deny this [is] largely an ethnic conflict between Western and Russian Ukrainians, as it has been since 2014).

And the thing is all of these discussions rest on a assumption that seems ludicrous the second you stop and think about it: Ukraine is not the future of Warfare, these conditions will be almost impossible to ever create again.

Ukraine had a pre-war Nominal GDP of 199 billion USD. Officially this only declined to 160 billion in 2022 as a result of the war, but there’s good reason to think its actual internal private sector economy collapsed far further [given] it had collapsed from 177 billion in 2013 to 90 billion in 2015 as a result of the US backed Coup/Revolution.

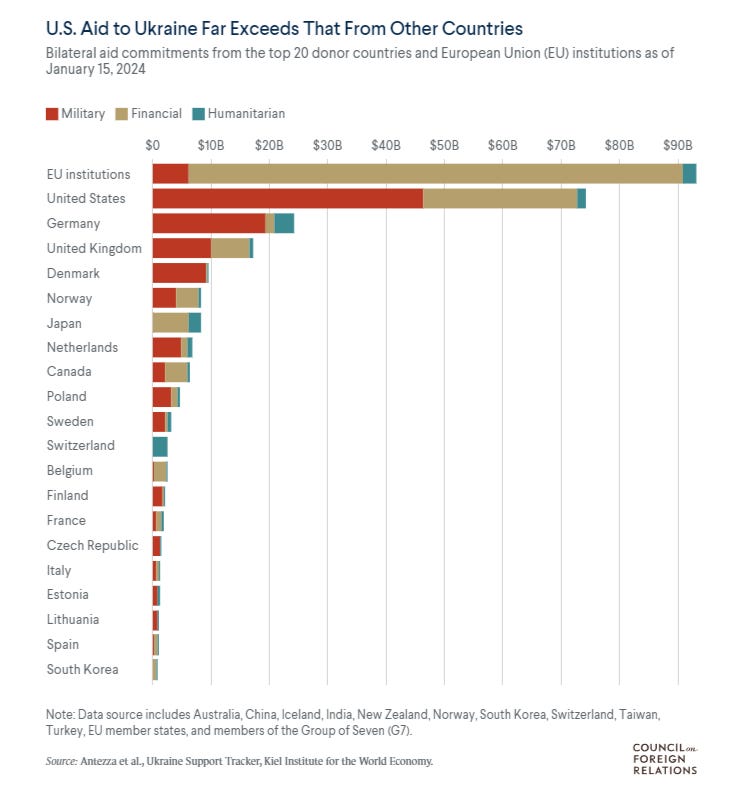

Indeed given the population flight, conscription, and impositions on the populace, it is very likely a SUPER-MAJORITY of that 160 billion GDP in 2022, was actually the result of US and NATO pouring hundreds of billions into the country. Where it was either used or siphoned off as corruption.

Simply put Ukraine has received military, financial and other aid most like in excess of what its entire internal economy produced in the same period, and as of writing it’s still losing territory.

When commentators say this is a war between NATO and Russia they are almost entirely correct. If you combine all the economies that are funding, arming, or fighting on one side or the other of this war you get a majority of the entire global economy.

And they have used all that money to pay off the Ukrainian regime to refuse any peace agreement, even ones their own negotiators had agreed to, and that were clearly in the best interest of the country … you know if you value hundreds of thousands of young men and not having your population collapse more than narrow stretches of land being bought up by Blackrock.

February 24, 2024

Never mind the unfunded liability … money printer go brrrr!

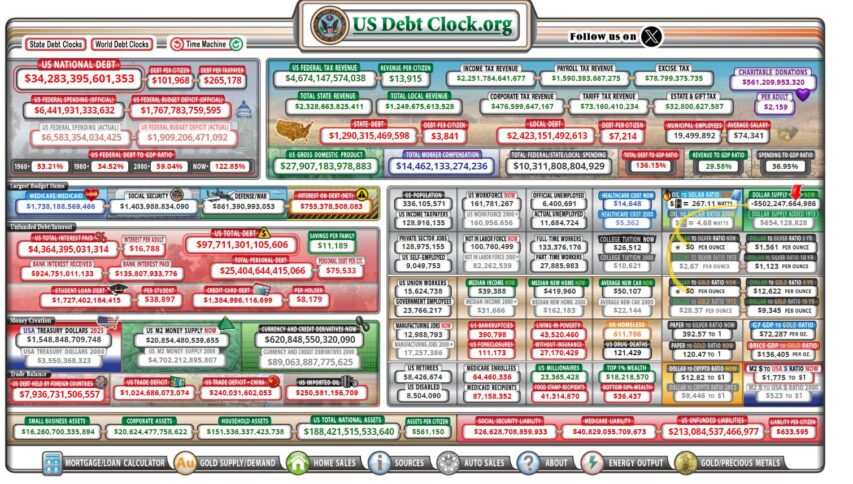

Kulak at Anarchonomicon points out that the US government’s debt situation — which was alarming 20 years ago — has continued to get worse every year:

Libertarian Economists have been predicting this collapse of the federal system would happen “By About 2030” since before 2008. I remember in high school in the early 2010s listening to Ron Paul lectures and visiting USDebtClock.com, this was a hot button issue after 2008 … (then of course there was no political will to do anything and everyone just stopped talking about it)

I honestly forget that everyone around me doesn’t already know this, this is so common and accepted in libertarian and economic circles, and everyone who knows it got bored of eyes glossing over when they tried to explain it (in an autistic panic) decades ago.

US Unfunded liabilities:

Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, US Debt, and Federal employee benefits and pensions, are all basically intergenerational ponzi schemes that require constant 1950s level population growth amongst the productive tax paying middle-class to maintain. By 2000 it was obvious this population growth was not happening, that population was beginning to age and collapse, and NO, the illegals at the border weren’t adequate replacements … (they weren’t adequate to prop up federal expenses in 2000 when they were still Mexican, now that they’re Guatemalan, Haitian, and Senegalese they’re almost certainly a net drain).

The Specter of Mass Boomer retirements with few to no children and grandchildren to replace them and pay for all the costs of their retirements and healthcare was maybe the slowest but most assured crisis ever to be seen in human history … Demographics is destiny.

This was a foreseen problem in 2000 when US Debt to GDP (just the portion that’s already been spent and interest has to be paid on) was 59% of GDP. Today the US Debt to GDP ratio is 122% of GDP whilst just in the past 24 years. Absolute US Federal Debt (not including state or local) has grown from 5.6 trillion dollars to 34 trillion dollars (102k per citizen: man, woman, and child). just the interest that has to be paid out of your tax dollars on that debt is set to eclipse ALL US Military spending sometime this year … And by 2028 Debt to GDP will be 150% (46.4 Trillion, 132k per citizen, 12 trillion more in 4 years, with no additional spending bills) and the Interest (at current estimates) will be over 2.5 trillion dollars, over a third of all Tax Dollars brought in will be spent on just interest, because dollar confidence has collapsed and the only way to keep inflation from destroying the dollar has been to radically raise the interest rates the Federal Reserve offers.

Now all that, That catastrophic state of things, is just the debt, the money that’s been spent … The real crisis is the Unfunded liabilities, all the promises the US has made to Boomers (who dominate the vote) and others about money they’re GOING to spend.

As of now total Unfunded liabilities stand at 213 trillion dollars, $633,000 per US Citizen (Man woman, and newborn babe)… These are all dollars the US has promised to pay to someone somewhere at some point: Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, Federal pensions, VA Benefits, etc. And cannot in any politically feasible way restructure or get out of.

If no one ever contributed another dime to social security, and in so doing was promised in turn significantly more than that dime (it’s a Ponzi scheme, it loses money in proportion to and at a greater rate than the money being contributed to it (every dollar you contribute you’re promised multiple dollars in return, and your dollar is not invested, it just pays off previous contributors)) … If everything froze and every young person was locked out of ever receiving Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid, the Unfunded Liability would be $633k per every man, woman, and child … that’d be the debt a newborn American would be born with.

However because it is NOT frozen and it will not be, by 2028 that number will Rise to $837k and an ordinary household of 4 will have seen their, politically unavoidable, family obligation in future tax payments to the federal government increase by $804,000 in just 4 years.

If your response is that your family doesn’t even make 804k in 4 years and there’s no way you could ever pay that much in 4 years given its just going to increase at a faster rate the next 4 years … CONGRATULATIONS! 90% of families don’t make that much, and less than 1% of families could ever afford to pay that much in taxes in a 4 year time.

This has been slowly growing for decades, and in the late 2000s and 2010s Ron Paul types were screaming that those Benefits needed to be reformed NOW (in 2008) or they’d drown America. But of course, cutting benefits is political Anathema to boomers, so nothing was done …