Consider the Reformation. I’m in no way qualified to walk you through all the various doctrinal issues, but in this case a superficial analysis is not only sufficient, it’s actually better. Instead of getting lost in the theological weeds, I want to focus on the process. So let’s stipulate for the sake of argument that nothing Luther said was all that original, theologically — you can find pretty much any tenet of “Lutherism” (as it then was) somewhere in the past, often among the Church Fathers (the “double predestination” that drove Calvinists insane is straight out of St. Augustine, for example). Wyclif, Hus, Nicholas of Cusa, Marsilius of Padua, all those guys were proto-Luthers, at least in part.

The thing about Luther, then, wasn’t what he said, so much as how he said it.

Martin Luther was the world’s first spin doctor. Though he insisted for a long time that his famous 95 Theses were, and were always intended to be, a scholastic debate between clergymen, Luther mastered the use of printed propaganda. His opponents soon followed, or tried to, in an ever-increasing spiral of printed viciousness. Mutatis mutandis, the exchanges between Luther, Erasmus, Thomas More (to say nothing of a thousand lesser lights) and their opponents all sound shockingly Current Year. They’re snarky and waspish at best, grotesque ad hominem at worst. Modern flame wars have nothing on the way Thomas More and William Tyndale tore into each other, for instance, and More and Tyndale were rank amateurs compared to Luther.

As with the Current Year, where being first on social media is the only criterion that matters, so the printing press injected something very like “hot takes” into the late-Medieval intellectual atmosphere. If you tried to respond to your opponents the old-fashioned way — with closely reasoned, heavily cited arguments, on parchment, hand-copied by monks — you might win the intellectual battle … 500 years later, among historians who thank you for providing such a useful glimpse into late-Medieval mentalités, but in your own time you’d get fired at best, get burned at the stake at worst, if you didn’t respond instantly, in kind.

The printing press, in other words, represented a quantum leap in the velocity of information. Those who grasped its fundamentals prospered, while those who fell behind perished. King Henry VIII, for instance, fatally damaged his cherished intellectual reputation when he deigned to attack to Luther in person. Luther hit back with a tirade that wouldn’t be out of place on Twitter1, and Henry responded in kind, and now the king, who was hip-deep in self-inflicted shit by that point, had to drop the fight. Having been publicly abused by a mere ex-monk, he had to quit the field with his tail between his legs.

Severian, “Velocity of Information”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-08-10.

1. Again, mutatis mutandis. Though this sounds to modern ears like an abject apology on Luther’s part (“especially as I am the offscouring of the world, a mere worm who ought only to live in contemptuous neglect”, etc.), in context it’s a vicious attack. For one thing, what’s a great king like Henry doing responding to a “mere worm”? And Henry had to know, since Wolsey did nothing without his master’s orders … except everyone had heard the rumors that Henry was just a dimwitted playboy, and Cardinal Wolsey was really the king in all but name, so maybe he didn’t know. Either way Henry, who prided himself on being an intellectual, was a fool. That’s the kind of thing that would get you executed in the 16th century, and here’s this “mere worm” publishing it, for all the world to see, with no possibility of reprisal from a supposedly puissant monarch.

August 20, 2024

August 19, 2024

Bret Devereaux on Nathan Rosenstein’s Rome at War (2004)

Although Dr. Devereaux is taking a bit of time away from the more typical blogging topics he usually covers on A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, he still discusses books related to his area of specialty:

For this week’s book recommendation, I want to recommend N. Rosenstein, Rome at War: Farms, Families and Death in the Middle Republic (2004). This is something of a variation from my normal recommendations, so I want to lead with a necessary caveat: this book is not a light or easy read. It was written for specialists and expects the reader to do some work to fully understand its arguments. That said, it isn’t written in impenetrable “academese” – indeed, the ideas here are very concrete, dealing with food production, family formation, mortality and military service. But they’re also fairly technical and Rosenstein doesn’t always stop to recap what he has said and draw fully the conclusions he has reached and so a bit of that work is left to the reader.

That said, this is probably in the top ten or so books that have shaped me as a scholar and influenced my own thinking – as attentive readers can no doubt recall seeing this book show up a lot in my footnotes and citations. And much like another book I’ve recommended, Landers, The Field and the Forge: Population, Production and Power in the Pre-Industrial West (2003), this is the sort of book that moves you beyond the generalizations about ancient societies you might get in a more general treatment (“low productivity, high mortality, youth-shifted age profile, etc.”) down to the actual evidence and methods we have to estimate and understand that.

Fundamentally, Rome at War is an exercise in “modeling” – creating (fairly simple) statistical models to simulate things for which we do not have vast amounts of hard data, but for which we can more or less estimate. For instance, we do not have the complete financial records for a statistically significant sample of Roman small farmers; indeed, we do not have such for any Roman small farmers. So instead, Rosenstein begins with some evidence-informed estimates about typical family size and construction and combines them with some equally evidence-informed estimates about the productivity of ancient farms and their size and then “simulates” that household. That sort of approach informs the entire book.

Fundamentally, Rosenstein is seeking to examine the causes of a key Roman political event: the agrarian land-reform program of Tiberius Gracchus in 133, but the road he takes getting there is equally interesting. He begins by demonstrating that based on what we know the issue with the structure of agriculture in Roman Italy was not, strictly speaking “low productivity” so much as inefficient labor allocation (a note you will have seen me come back to a lot): farms too small for the families – as units of labor – which farmed them. That is a very interesting observation generally, but his point in reaching it is to show that this is why Roman can conscript these fellows so aggressively: this is mostly surplus labor so pulling it out of the countryside does not undermine these households (usually). But that pulls a major pillar – that heavy Roman conscription undermined small freeholders in Italy in the Second Century – out of the traditional reading of the land reforms.

Instead, Rosenstein then moves on to modeling Roman military mortality, arguing that, based on what we know, the real problem is that Rome spends the second century winning a lot. As a result, lots of young men who normally might have died in war – certainly in the massive wars of the third century (Pyrrhic and Punic) – survived their military service, but remained surplus to the labor needs of the countryside and thus a strain on their small households. These fellows then started to accumulate. Meanwhile, the nature of the Roman census (self-reported on the honor system) and late second century Roman military service (often unprofitable and dangerous in Spain, but not with the sort of massive armies of the previous centuries which might cause demographically significant losses) meant that more Romans might have been dodging the draft by under-reporting in the census. Which leads to his conclusion: when Tiberius Gracchus looks out, he sees both large numbers of landless Romans accumulating in Rome (and angry) and also falling census rolls for the Roman smallholder class and assumes that the Roman peasantry is being economically devastated by expanding slave estates and his solution is land reform. But what is actually happening is population growth combined with falling census registration, which in turn explains why the land reform program doesn’t produce nearly as much change as you’d expect, despite being more or less implemented.

Those conclusions remain both important and contested. What I think will be more valuable for most readers is instead the path Rosenstein takes to reach them, which walks through so much of the nuts-and-bolts of Roman life: marriage patterns, childbearing patterns, agricultural productivity, military service rates, mortality rates and so on. These are, invariably, estimates built on estimates of estimates and so exist with fairly large “error bars” and uncertainty, but they are, for the most part, the best the evidence will support and serve to put meat on the bones of those standard generalizing descriptions of ancient society.

If you’ve never worked in the private sector, you have no idea how regulations impact businesses

In the National Post, J.D. Tuccille explain why Democratic candidates like Kamala Harris and Tim Walz who have spent little or no time in the non-government world have such rosy views of the benefits of government control with no concept of the costs such control imposes:

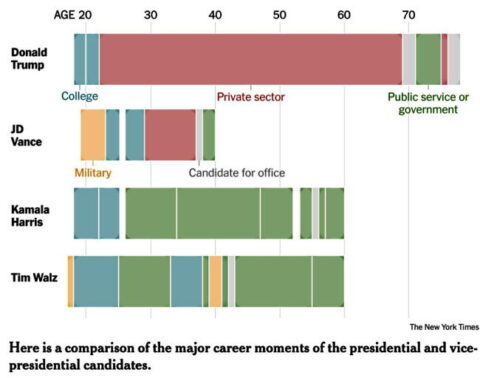

The respective public versus private sector experiences of the 2024 Presidential/Vice Presidential candidates.

New York Times

In broad terms, Democrats have faith in government while the GOP is skeptical — though a lot of Republicans are willing to suspend disbelief when their party controls the executive branch.

The contrast between the two parties can be seen in stark terms in the resumes of the two presidential and vice-presidential tickets. The New York Times made it easier to compare them earlier this month when it ran charts of the career timelines of Trump, J.D. Vance, Kamala Harris and Tim Walz. Their roles at any given age were colour-coded for college, military, private sector, public service or politics, federal government and candidate for federal office.

Peach is the colour used by the Times to indicate employment in the private sector, which produces the opportunities and wealth that are mugged away (taxation is theft by another name, after all) to fund all other sectors. It appears under the headings of “businessman” and “television personality” for Trump and as “lawyer and venture capitalist” for Vance. But private-sector peach appears nowhere in the timelines for Harris and Walz. Besides, perhaps, some odd jobs when they were young, neither of the Democrats has worked in the private sector.

Now, not all private-sector jobs are created equal. Some of the Republican presidential candidate’s ventures, like Trump University, have been highly sketchy, as are some of his practices — he’s openly boasted about donating to politicians to gain favours (though try to do business in New York without greasing palms). I’m not sure I’d want The Apprentice on my resume. But there must be some value to working on the receiving end of the various regulations and taxes government officials foist on society rather than spending one’s career brainstorming more rules without ever suffering the consequences.

In 1992, former U.S. senator and 1972 Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern penned a column for the Wall Street Journal about the challenges he encountered investing in a hotel after many years in government.

“In retrospect, I … wish that during the years I was in public office, I had had this firsthand experience about the difficulties business people face every day,” he wrote. He bemoaned “federal, state and local rules” passed with seemingly good intentions but little thought to the burdens and costs they imposed.

The lack of private sector stints in the career timelines of Harris and Walz means that, like pre-hotel McGovern, they’ve never had to worry about what it’s like to suffer the policies of a large and intrusive government.

That said, it’s possible to overstate the lessons learned by Republicans and Democrats from their different experiences. Vance, despite having worked to fund and launch businesses, has, since being elected to the U.S. Senate, advocated capturing the regulatory state and repurposing it for political uses, including punishing enemies.

Not only does power corrupt, but it does so quickly.

The US Navy’s mis-managed decline continues

Niccolo Soldo from his weekend wrap-up of various news articles that caught his eye:

Artist’s rendering of the US Navy’s FFG(X) Constellation-class guided missile frigate. Initial contract awarded 30 April, 2020, but delivery of the first ship is not expected until 2029 due to design changes and other issues.

US Navy image via Wikimedia Commons.

One data point that works in favour of American Declinism is the US Navy’s inability to not just keep up with the Chinese in terms of the production of ships, but to also maintain its own production output. Many lightly-armed littoral combat ships have been retired, for example, with nothing to replace them.

These production setbacks have been pointed out to me, with one mutual on Twitter/X reiterating the point so that I get it (I do!). This is an actual problem that requires solving, and fast. It is partially to blame for the Americans effectively ceding the Red Sea to the Houthis (for now).

AP has done a partial deep-dive (horrible language here, I apologize) on this issue:

The labor shortage is one of myriad challenges that have led to backlogs in ship production and maintenance at a time when the Navy faces expanding global threats. Combined with shifting defense priorities, last-minute design changes and cost overruns, it has put the U.S. behind China in the number of ships at its disposal — and the gap is widening.

Navy shipbuilding is currently in “a terrible state” — the worst in a quarter century, says Eric Labs, a longtime naval analyst at the Congressional Budget Office. “I feel alarmed,” he said. “I don’t see a fast, easy way to get out of this problem. It’s taken us a long time to get into it.”

Marinette Marine is under contract to build six guided-missile frigates — the Navy’s newest surface warships — with options to build four more. But it only has enough workers to produce one frigate a year, according to Labs.

A lot of the guys who know how to do this work are retiring or have already retired. Sound familiar?

One of the industry’s chief problems is the struggle to hire and retain laborers for the challenging work of building new ships as graying veterans retire, taking decades of experience with them.

Shipyards across the country have created training academies and partnered with technical colleges to provide workers with the skills they need to construct high-tech warships. Submarine builders and the Navy formed an alliance to promote manufacturing careers, and shipyards are offering perks to retain workers once they’re hired.

Andreini trained for his job at Marinette through a program at Northeast Wisconsin Technical College. Prior to that, he spent several years as a production line welder, making components for garbage trucks. He said some of his buddies are held back by the stigma that shipbuilding is a “crappy work environment, and it’s unsafe.”

The problem:

Much of the blame for U.S. shipbuilding’s current woes lies with the Navy, which frequently changes requirements, requests upgrades and tweaks designs after shipbuilders have begun construction.

That’s seen in cost overruns, technological challenges and delays in the Navy’s newest aircraft carrier, the USS Ford; the spiking of a gun system for a stealth destroyer program after its rocket-assisted projectiles became too costly; and the early retirement of some of the Navy’s lightly armored littoral combat ships, which were prone to breaking down.

The Navy vowed to learn from those past lessons with the new frigates they are building at Marinette Marine. The frigates are prized because they’re less costly to produce than larger destroyers but have similar weapon systems.

Now check this out:

The Navy chose a ship design already in use by navies in France and Italy instead of starting from scratch. The idea was that 15% of the vessel would be updated to meet U.S. Navy specifications, while 85% would remain unchanged, reducing costs and speeding construction.

Instead, the opposite happened: The Navy redesigned 85% of the ship, resulting in cost increases and construction delays, said Bryan Clark, an analyst at the Washington-based think tank Hudson Institute. Construction of the first-in-class Constellation warship, which began in August 2022, is now three years behind schedule, with delivery pushed back to 2029.

The final design still isn’t completed.

Shifting threats:

Throughout its history, the Navy has had to adapt to varying perils, whether it be the Cold War of past decades or current threats including war in the Middle East, growing competition from Chinese and Russian navies, piracy off the coast of Somalia and persistent attacks on commercial ships by Houthi rebels in Yemen.

And that’s not all. The consolidation of shipyards and funding uncertainties have disrupted the cadence of ship construction and stymied long-term investments and planning, says Matthew Paxton of the Shipbuilders Council of America, a national trade association.

“We’ve been dealing with inconsistent shipbuilding plans for years,” Paxton said. “When we finally start ramping up, the Navy is shocked that we lost members of our workforce.”

How is the US Navy supposed to protect Taiwan from a potential Chinese invasion?

Evolution of WW2 German Tank Destroyers

The Tank Museum

Published May 3, 2024 19 productsUsed extensively by the German army of World War Two, the “tank destroyer” was developed to counter the increasing dominance of the tank on the battlefield.

Germany would field a massive 18 different types of tank destroyer in World War Two – compared with the 7 or 8 different types used by US, British and Commonwealth forces. One of these in particular, Sturmgeschütz III, would destroy more tanks than any other AFV in the entire conflict.

In this video we look at the development, strengths and weaknesses of German tank destroyers: from the 17 tonne Hetzer to the massive 70 tonne Jagdtiger — the heaviest tracked vehicle of the War.

00:00 | Introduction

00:59 | The First Tank Destroyers

04:14 | Avoiding Close Combat

06:59 | Jagdpanther

12:05 | Jagdtiger

15:31 | Hetzer

18:01 | Stug III

22:51 | ConclusionThis video features archive footage courtesy of British Pathé.

#tankmuseum #jagdpanther #stugiii #hetzer #jagdtiger

QotD: Government efficiency

Our greatest threat today comes from government’s involvement in things that are not government’s proper province. And in those things government has a magnificent record of failure.

Ronald Reagan, quoted in “Inside Ronald Reagan”, Reason, 1975-07.

August 18, 2024

Hirohito Announces Surrender – War Continues – WW2 – Week 312 – August 17, 1945

World War Two

Published 17 Aug 2024Hirohito broadcasts Japan’s surrender to the world- despite an attempted to coup to prevent it from happening, and much of the world celebrates, but the war isn’t really over. The Soviets are busy invading Manchuria, and there’s revolution in Vietnam and Indonesia.

00:00 Intro

00:22 Recap

00:49 Attempted Coup In Japan

04:12 Hirohito Surrenders

08:54 Japanese Surrender In China

12:05 Soviets In Manchuria

17:52 Revolution In Vietnam

20:33 Summary

21:07 Conclusion

(more…)

A view of the near future – “What if calling someone stupid was illegal?”

Christopher Gage suspects that Lionel Shriver’s new book Mania didn’t require a lot of deep thinking about possible future trends, just a few glances at the headlines in British newspapers would provide all the inspiration necessary:

Lionel Shriver’s novel, Mania, asks “What if calling someone stupid was illegal?”

Set in an alternate timeline eerily flirtatious with our own, Mania depicts a world in which intelligence and competence, those oppressive agents of the modern bête noire — contrast — provoke outraged mobs.

The Mental Parity Movement demands a Khmer-Rouge-style Year Zero. To suggest the existence of differing abilities and competencies is to be “brain-vain”. In this final “great civil rights fight”, stupidity is euphemised as “alternative processing”. The mob cancels Frasier for brain vanity. After regulations prevent Pfizer from hiring qualified scientists, a toxic vaccine lays waste to millions.

The protagonist, a free-thinking academic named Pearson, cancels herself after she adds Dostoevsky’s The Idiot to her class syllabus. But the book is not the offending item. The word “idiot” is illegal. So too, is the “D-Word”. Pearson falls foul of social services after calling her seven-year-old daughter “dumb”. Her daughter grasses her up for this most heinous offence. For her crimes, Pearson endures a mandatory course entitled “Cerebral Acceptance and Semantic Sensitivity”.

Akin to our culture, mass neurosis devours that of Mania. The citizens scour the earth for evidence of the gravest offence: cognitive bigotry.

The Mental Parity Movement even renames “sage” — stripping the haughty herb of its sapiosexual swagger.

Mania imagines a world in which mediocrity is brilliance and where platitude is profundity. I suspect Shriver wasted little time on research. Turning on one’s television furnishes a commonplace book with a bottomless wealth of material.

This week, Harry and Meghan embarked on an unroyal tour of Colombia. On the agenda was a summit on misinformation and online harm. At this “responsible digital future” fandango, the former soap actress and the former royal spermatozoa relayed their fears. Essentially, hordes of toothless oiks with Wi-Fi often say nasty things online.

On stage, Harry adopted the pose of the modern soothsayer. His tieless open collar oozed Sicilian ease.

Speaking in Adverb English, Harry avoided anything as threatening or as harmful as a declarative sentence. Harry talks as if everything is a question as not to arouse predators. The Prince droned on, auditioning the Californication of his mother tongue. The same mother tongue Harry’s ancestors spread around the globe via what some may deign to be less than inclusive methods.

How can I put this in Mania-approved euphemism? Harry is minimally exceptional. Harry is to intelligent thought what lead pipes are to potable water.

.30-06 M1918 American Chauchat – Doughboys Go to France

Forgotten Weapons

Published May 4, 2024When the US entered World War One, the country had a grand total of 1,453 machine guns, split between four different models. This was not a useful inventory to equip even a single division headed for France, and so the US had to look to France for automatic weapons. In June 1917 Springfield Armory tested a French CSRG Chauchat automatic rifle, and found it good enough to inquire about making an American version chambered for the .30-06 cartridge. This happened quickly, and after testing in August 1917, a batch of 25,000 was ordered. Of these, 18,000 were delivered and they were used to arm several divisions of American troops on the Continent.

Unfortunately, the American Chauchat was beset by extraction problems. These have today be traced to incorrectly cut chambers, which were slightly too short and caused stuck cases when the guns got hot. It is unclear exactly what caused the problem, but the result was that most of the guns were restricted to training use (as best we can tell today), and exchanged for French 8mm Chauchats when units deployed to the front. Today, American Chauchats are extremely rare, but also very much underappreciated for their role as significant American WWI small arms.

(more…)

QotD: Cell phones on airplanes

The thought of people being able to use cell phones on airplanes during flight is almost too horrible to contemplate. But I understand why the airlines are considering it: They’ve run out of new ways to make flying unpleasant. Long lines, inexplicable delays, lost baggage, no food, filthy airplanes, unhappy workers (is anyone else worried about planes being flown by despondent pilots who’ve had their pensions stolen from them?) — allowing people to use their cell phones is the only way for the airlines to freshen up the hell they’ve created for us.

Andrew Sullivan, “Terror Cells”, AndrewSullivan.com, 2005-08-09.

August 17, 2024

Forgotten War Ep1 – Witness the Rising Sun

HardThrasher

Published Aug 14, 2024In January 1942 the Japanese Army poured over the border with Burma, and pushed back the Indian and British Armies to the border with Burma. Today we look at how that disaster came about, why and the first phase of the campaign

(more…)

“The notion of a pre-existing Palestinian state is a modern fabrication that ignores the region’s actual history”

Debunking some of the common talking points about the Arab-Israeli conflicts down to the present day:

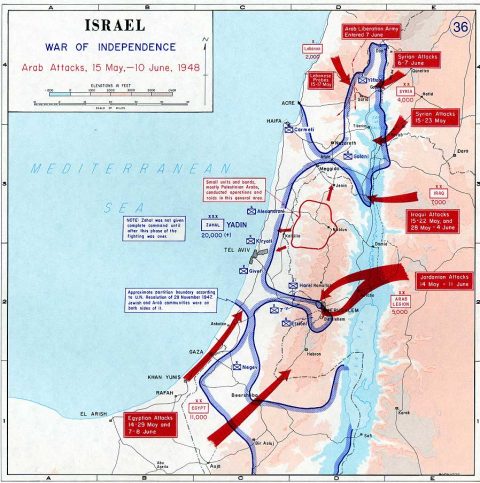

Arab attacks in May and June 1948.

United States Military Academy Atlas, Link.

Before Israel declared independence in 1948, the region now known as Israel, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip was part of the British Mandate for Palestine, which was established by the League of Nations after the fall of the Ottoman Empire in the First World War.

Under Ottoman rule, the area was divided into various administrative districts, with no distinct political entity known as “Palestine”. The concept of a Palestinian national identity emerged in the 20th century, largely in response to the Zionist movement and increased Jewish immigration in the area.

However, there was never a Palestinian state, flag or anthem. The notion of a pre-existing Palestinian state is a modern fabrication that ignores the region’s actual history.

The modern State of Israel’s legitimacy is rooted in international law and global recognition. On Nov. 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 181, known as the “Partition Plan”, proposing two states — one Jewish and one Arab.

The Jewish community accepted the plan, demonstrating a willingness to compromise for peace. However, the Arab states rejected it, refusing to recognize any Jewish state, and instead launched a military assault on Israel following its declaration of independence on May 14, 1948.

Another pervasive myth is the “Nakba” or “catastrophe”, narrative, which claims that Palestinians were forcibly expelled by Israel in 1948. This version omits the critical context that it was the Arab nations that invaded Israel, causing many Arabs to be expelled or flee their homes.

Rather than absorbing the displaced population, the surrounding Arab countries kept them in refugee camps, using them as pawns to pressure Israel. Organizations like UNRWA perpetuated this situation, keeping Palestinians in limbo rather than encouraging their integration into their host countries. This contrasts sharply with how other refugee populations have been handled, where integration and resettlement are the norm.

The land referred to as “Palestine” has always been inherently Jewish. The Jewish people have maintained a continuous presence there for thousands of years, long before Islam or the Arab conquests.

Caesar Marches on Rome – Historia Civilis Reaction

Vlogging Through History

Published Apr 23, 2024See the original here –

• Caesar Marches on Rome (49 B.C.E.)

See “Caesar Crosses the Rubicon” here –

• Caesar Crosses the Rubicon – Historia…#history #reaction

QotD: Sheep and wool in the ancient and medieval world

Our second fiber, wool, as readers may already be aware, comes from sheep (although goat and horse-hair were used rarely for some applications; we’re going to stick to sheep’s wool here). The coat of a sheep (its fleece) has three kinds of fibers in it: wool, kemp and medullated fibers. Kemp fibers are fairly weak and brittle and won’t accept dye and so are generally undesirable, although some amount of kemp may end up in wool yarn. Likewise, medullated fibers are essentially hair (rather than wool) and lack elasticity. But the wool itself, composed mostly of the protein keratin along with some lipids, is crimped (meaning the fibers are not straight but very bendy, which is very valuable for making fine yarns) and it is also elastic. There are reasons for certain applications to want to leave some of the kemp in a wool yarn that we’ll get to later, but for the most part it is the actual wool fibers that are desirable.

Sheep themselves probably descend from the wild mouflon (Ovis orientalis) native to a belt of uplands bending over the northern edge of the fertile crescent from eastern Turkey through Armenia and Azerbaijan to Iran. The fleeces of these early sheep would have been mostly hair and kemp rather than wool, but by the 4th millennium BC (as early as c. 3700 BC), we see substantial evidence that selective breeding for more wool and thicker coats has begun to produce sheep as we know them. Domestication of course will have taken place quite a bit earlier (selective breeding is slow to produce such changes), perhaps around 10,000 BC in Mesopotamia, spreading to the Indus river valley by 7,000 BC and to southern France by 6,000 BC, while the replacement of many hair breeds of sheep with woolly sheep selectively bred for wool production in Northern Mesopotamia dates to the third century BC.1 That process of selective breeding has produced a wide variety of local breeds of sheep, which can vary based on the sort of wool they produce, but also fitness for local topography and conditions.

As we’ve already seen in our discussion on Steppe logistics, sheep are incredibly useful animals to raise as a herd of sheep can produce meat, milk, wool, hides and (in places where trees are scarce) dung for fuel. They also only require grass to survive and reproduce quickly; sheep gestate for just five months and then reach sexual maturity in just six months, allowing herds of sheep to reproduce to fill a pasture quickly, which is important especially if the intent is not merely to raise the sheep for wool but also for meat and hides. Since we’ve already been over the role that sheep fill in a nomadic, Eurasian context, I am instead going to focus on how sheep are raised in the agrarian context.

While it is possible to raise sheep via ranching (that is, by keeping them on a very large farm with enough pastureland to support them in that one expansive location) and indeed sheep are raised this way today (mostly in the Americas), this isn’t the dominant model for raising sheep in the pre-modern world or even in the modern world. Pre-modern societies generally operated under conditions where good farmland was scarce, so flat expanses of fertile land were likely to already be in use for traditional agriculture and thus unavailable for expansive ranching (though there does seem to be some exception to this in Britain in the late 1300s after the Black Death; the sudden increase in the cost of labor – due to so many of the laborers dying – seems to have incentivized turning farmland over to pasture since raising sheep was more labor efficient even if it was less land efficient and there was suddenly a shortage of labor and a surplus of land). Instead, for reasons we’ve already discussed, pastoralism tends to get pushed out of the best farmland and the areas nearest to towns by more intensive uses of the land like agriculture and horticulture, leaving most of the raising and herding of sheep to be done in the rougher more marginal lands, often in upland regions too rugged for farming but with enough grass to grow. The most common subsistence strategy for using this land is called transhumance.

Transhumant pastoralists are not “true” nomads; they maintain permanent dwellings. However, as the seasons change, the transhumant pastoralists will herd their flocks seasonally between different fixed pastures (typically a summer pasture and a winter pasture). Transhumance can be either vertical (going up or down hills or mountains) or horizontal (pastures at the same altitude are shifted between, to avoid exhausting the grass and sometimes to bring the herds closer to key markets at the appropriate time). In the settled, agrarian zone, vertical transhumance seems to be the most common by far, so that’s what we’re going to focus on, though much of what we’re going to talk about here is also applicable to systems of horizontal transhumance. This strategy could be practiced both over relatively short distances (often with relatively smaller flocks) and over large areas with significant transits (see the maps in this section; often very significant transits) between pastures; my impression is that the latter tends to also involve larger flocks and more workers in the operation. It generally seems to be the case that wool production tended towards the larger scale transhumance. The great advantage of this system is that it allows for disparate marginal (for agriculture) lands to be productively used to raise livestock.

This pattern of transhumant pastoralism has been dominant for a long time – long enough to leave permanent imprints on language. For instance, the Alps got that name from the Old High German alpa, alba meaning which indicated a mountain pasturage. And I should note that the success of this model of pastoralism is clearly conveyed by its durability; transhumant pastoralism is still practiced all over the world today, often in much the same way as it was centuries or millennia ago, with a dash of modern technology to make it a bit easier. That thought may seem strange to many Americans (for whom transhumance tends to seem very odd) but probably much less strange to readers almost anywhere else (including Europe) who may well have observed the continuing cycles of transhumant pastoralism (now often accomplished by moving the flocks by rail or truck rather than on the hoof) in their own countries.

For these pastoralists, home is a permanent dwelling, typically in a village in the valley or low-land area at the foot of the higher ground. That low-land will generally be where the winter pastures are. During the summer season, some of the shepherds – it does not generally require all of them as herds can be moved and watched with relatively few people – will drive the flocks of sheep up to the higher pastures, while the bulk of the population remains in the village below. This process of moving the sheep (or any livestock) over fairly long distances is called droving and such livestock is said to be moved “on the hoof” (assuming it isn’t, as in the modern world, transported by truck or rail). Sheep are fairly docile animals which herd together naturally and so a skilled drover can keep large flock of sheep together on their own, sometimes with the assistance of dogs bred and trained for the purpose, but just as frequently not. While cattle droving, especially in the United States, is often done from horseback, sheep and goats are generally moved with the drovers on foot.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part I: High Fiber”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-05.

1. On this, note E. Vila and D. Helmer, “The Expansion of Sheep Herding and the Development of Wool Production in the Ancient Near East” in Wool Economy in the Ancient Near East and the Aegean, eds. C. Breniquet and C. Michel (2014), which has the archaeozoological data).