“You’re in a heap o’ trouble, boy.” Or girl. What follows are the reasons — or at least the big ones — why you’re so thoroughly screwed, along with some suggestions for self-help at the end.

You tend to loathe Boomers and Generation X, I know. I don’t actually blame you for that, at least not entirely. Some of you, though, the Millennials who lump all the above together, without exception, strike me as singularly stupid and ignorant.

Moreover, the reasons you have for loathing them are somewhat misplaced. You tend to think — not without some reason — that the Boomers, especially, robbed their future, which is to say you, personally, to pay for largesse for themselves in the present.

It’s true enough, but it is neither the really awful thing they did to you nor does the complaint portray you in any particularly favorable light. “Those damned Boomers; they took everything and now there’s nothing left for us.” Yeah … you know what that sounds like? It sounds like the whining of one group of thieves over the success of a better or, in this case, merely luckier group of thieves who got to the big haul first. Yes, it really does.

Sorry, but the damage the Boomers and Xers did to you wasn’t primarily fiscal. No, no, the damage they did – or allowed – was to you, as a person. That’s the real crime. They didn’t just rob you of some money in advance. They didn’t just vote for a series of politicians and political programs and giveaways that ran the economy into the ground.

No, they stole from you — or allowed others to steal from you — some key elements of personhood, especially the ability to engage in critical, logical thinking. That’s right, you were not educated, whether in kindergarten or in the kindergartenesque, safe space segregated, snowflake sanctuary schools we call colleges and universities. Yes, these institutions of miseducation were supposed to teach you how to think. Instead, they taught you what to think and stunted your native ability to think. If you ever start to spout bright green feathers? Yes, this is the reason why; your teachers demanded that you become a parrot.

Tom Kratman, “It’s Up to You, Millennials. Deflect or Be Doomed”, Milo, 2017-12-06.

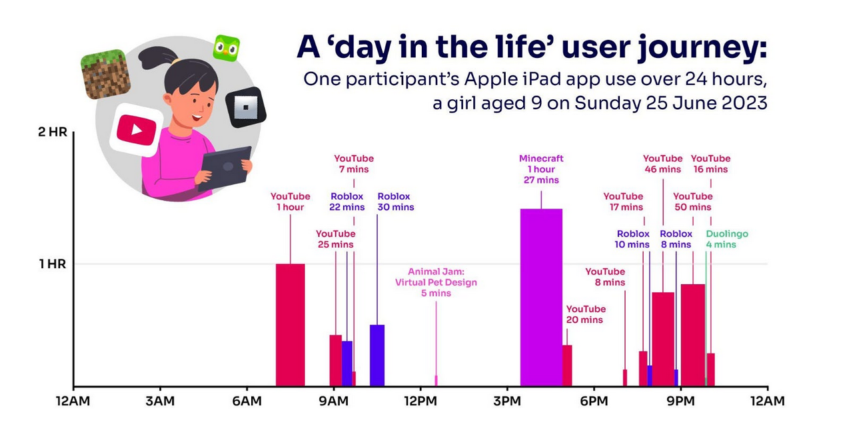

May 2, 2024

QotD: Fomenting inter-generational hatred

May 1, 2024

The Supreme Court of Canada has created “Charter-free zones” in Canada

A recent Supreme Court of Canada decision to allow the Charter of Rights and Freedoms to be overridden in cases where First Nations’ laws conflict with the rights guaranteed to all Canadians by the Charter:

Governments of the over 600 First Nations bands and self-governing Indigenous communities across Canada have been given the green light by the Supreme Court to, in their laws, legally abrogate and override the civil liberties of their band members and citizens.

In its Dickson v. Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation decision the Court ruled that so long as an Indigenous government law “protects Indigenous difference — understood by the collective as interests connected to Aboriginal cultural difference, Aboriginal prior occupancy, Aboriginal prior sovereignty or Aboriginal participation in the treaty process” — then, despite the fact that the law infringes the Charter rights of its citizens, those Charter rights cannot have any application or be given any effect to.

Four of the seven Judges who ruled on the case ruled that the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms prima facie applies to Indigenous government laws, but notwithstanding that, if the law is to “protect Indigenous difference”, and the exercise of a Charter right would have the effect of diminishing that “Indigenous difference”, then section 25 of the Constitution Act “shields” the law from Charter application.

A fifth Judge ruled that section 25 meant that the Charter didn’t apply at all to Indigenous government laws, not even prima facie.

Two of the seven judges dissented, one of whom very significantly was Madame Justice O’Bonsawin, the Indigenous person appointed to the Supreme Court supposedly to import an “Indigenous perspective” into its judgments. These two dissenting Justices wrote correctly that the majority opinion creates “Charter-free zones” in Canada. They further wrote:

Minorities with Indigenous communities (will) not be protected from the actions of their own governments. All Canadians, including Indigenous people, need constitutional tools to hold their governments accountable for breaches of their entrenched rights and freedoms. It is against the purposes of the Charter and s. 25, as well as being profoundly inequitable, to deny members of self-governing Indigenous nations similar, rights, remedies and recourse.

There are more than 1.8 million Indigenous Canadians, two-thirds of whom live “off-reserve” in Canada’s towns and cities. The Supreme Court of Canada has deprived all these Canadians of the protections afforded by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms on their home reserves and territories.

The Court employed cloud castle reasoning to bring about this illiberal and un-Canadian result, heavy on empty verbal assertions and abstractions with little relation to practical life.

Cloud castles are pleasant and charming to conjure up, even more so because they have no foundations.

The factual foundations of the Court’s decision, such as they, like those of cloud castles, are mainly imaginary. To the extent that may exist in reality, they are wrong.

In an earlier article the writer wrote on this case Cindy Dickson discussed the discriminatory, black sheep treatment she faced when trying to run for office in Vuntut Gwitchin.

The article pointed out other negative, First Nations realities ignored by the majority of the Supreme Court of Canada in its judgement: the “banana republic” nature of small Indigenous governments, and alpha-type band chiefs and councils — “colonizers of their own people” — overseeing a conflicted, family-based system of self-dealing and crony capitalism.

Indigenous Justice O’Bonsawin, as part of her “Indigenous perspective”, expressly acknowledged these entrenched negatives and listed other illiberal aspects of the “Indigenous difference” that the Charter exists to prevent or remedy: the unequal role given men in debating constitutional reforms, band membership rules that excluded some women and their children, election codes that prevent individuals from running for office on the basis of their gender, marital status or sexual orientation, and warrantless searches of homes.

The Death of Adolf Hitler – WW2 – Week 296B – April 30, 1945

World War Two

Published 30 Apr 2024Europe is broken, its cities in ruins, and millions have died in war and genocide. The world has risen against the Nazi threat, and now the Nazi leader cowers in his bunker under Berlin — this is how Adolf Hitler’s last 15 weeks unfold, and why he ultimately chooses suicide to escape responsibility for his actions.

Watch the Führerbunker special here:

Lobscouse, Hardtack & Navy Sea Cooks

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Jan 23, 2024Hearty meat and potato stew thickened with crushed hardtack (clack clack)

April 30, 2024

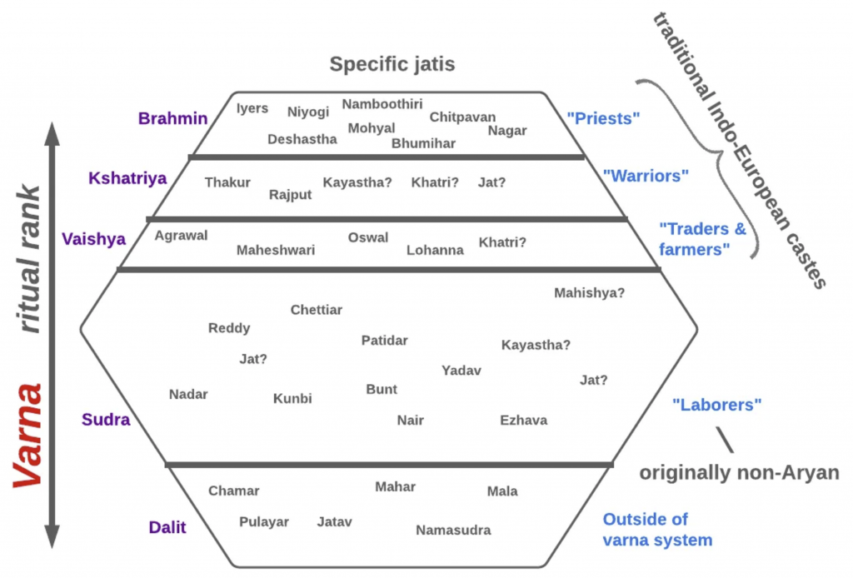

DNA and India’s caste system

Earlier this month, Palladium published Razib Khan‘s look at the genetic components of India’s Caste System:

Though the caste system dominates much of Indian life, it does not dominate Indian American life. At slightly over 1% of the U.S. population, only about half of Indian Americans identify as Hindu, the religion from which the broader categories of caste, or varna, emerge. While caste endogamy — marrying within one’s caste — in India remains in the range of 90%, in the U.S. only 65% of American-born Indians even marry other people of subcontinental heritage, and of these, a quick inspection of The New York Times weddings pages shows that inter-caste marriages are the norm. While tensions between the upper-caste minority and middle and lower castes dominate Indian social and political life, 85% of Indian Americans are upper-caste, broadly defined, and only about 1% are truly lower-caste. Ultimately, the minor moral panic over caste discrimination among a small minority of Americans is more a function of our nation’s current neuroses than the reality of caste in the United States.

But this does not mean that caste is not an important phenomenon to understand. In various ways, caste impacts the lives of the more than 1.4 billion citizens of India — 18% of humans alive today — whatever their religion. While the American system of racial slavery is four centuries old at most, India’s caste system was recorded by the Greek diplomat Megasthenes in 300 BC, and is likely far more ancient, perhaps as old as the Indus Valley Civilization more than 4,000 years ago. Indian caste has a deep pedigree as a social technology, and it illustrates the outer boundary of our species’ ability to organize itself into interconnected but discrete subcultures. And unlike many social institutions, caste is imprinted in the very genes of Indians today.

Of Memes and Genes

Beginning about twenty-five years ago, geneticists finally began to look at the variation within the Indian subcontinent, and were shocked by what they found. In small villages in India, Dalits, formerly called “outcastes,” were as genetically distinct from their Brahmin neighbors as Swedes were from Sicilians. In fact, a Brahmin from the far southern state of Tamil Nadu was genetically closer to a Brahmin from the northern state of Punjab then they were to their fellow non-Brahmin Tamils. Dalits from the north were similar to Dalits from the south, while the three upper castes, Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas, tended to cluster together against the Sudras.

Some scholars, like Nicholas Dirks, the former chancellor of UC Berkeley, argued for the mobility and dynamism of the caste system in their scholarship. But the genetic evidence seemed to indicate a level of social stratification that echoes through millennia. Across the subcontinent, Dalit castes engaged in menial and unsanitary labor and therefore were considered ritually impure. Meanwhile, Brahmins were the custodians of the Hindu Vedic tradition that ultimately bound the Indic cultures together with other Indo-European traditions, like that of the ancient Iranians or Greeks. Other castes also had their occupations: Kshatriyas were the warriors, while Vaishyas were merchants and other economically productive occupations.

Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas were traditionally the three “twice-born” castes, allowing them to study the Hindu scriptures after an initiatory ritual. The majority of the population were Sudras (or Shudras), India’s peasant and laboring majority. Shudras could not study the scriptures, and might be excluded from some temples and festivals, but they were integrated into the Hindu fold, and served by Brahmin priests. A traditional ethnohistory posits that elite Brahmin priests and Kshatriya rulers combined with Vaishya commoners formed the core of the early Aryan society in the subcontinent, with Shudras integrated into their tribes as indigenous subalterns. Outcastes were tribes and other assorted latecomers who were assimilated at the very bottom of the social system, performing the most degrading and impure tasks.

The caste system as a layered varna system with five classes and numerous integrated jati communities.

Razib KhanThis was the theory. Reality is always more complex. In India, the caste system combines two different social categories: varna and jati. Varna derives from the tripartite Indo-European system, in India represented by Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas. It literally translates as “color”, white for Brahmin purity, red for Kshatriya power, and yellow for Vaishya fertility. But India also has Shudras, black for labor. In contrast to the simplicity of varna, with its four classes, jati is fractured into thousands of localized communities. If varna is connected to the deep history of Indo-Aryans and is freighted with religious significance, jati is the concrete expression of Indian communitarianism in local places and times.

3 Chisel Mortise Method | Paul Sellers

Paul Sellers

Published Jan 19, 2024Sometimes, we avoid simple joinery because we believe it cannot be done well, and efficiently by hand. This mortise, 4″ long and 1 1/2″ deep by half an inch, took me around seven minutes.

In any hardwood, oak, for instance, it might take a minute longer, but no more. I did this video to show a technique using my mortise guide and a strategic way using three standard chisels and a method.

I am making a bed with eight mortise and tenon joints, and the mortise I chopped here is one of them.

Enjoy real woodworking with me; it doesn’t always need to be called work!

(more…)

QotD: The ambitious Roman’s path to glory and riches

The Romans, for one, admitted all the time that they screwed up … to themselves, in private (what passed for “private” in the ancient world, anyway). A big reason an ambitious man (a redundancy in ancient Rome) wanted to climb the cursus honorum was because that was the easiest way to get a field command, which was the easiest way to start a war with someone, which was the easiest route to riches and glory … provided you didn’t fuck it up. But if you did, the best thing to do was to go down fighting with your legions, because the minute you got back to Rome, there’d be ambitious men (again: redundant in context) lined up from here to Sicily waiting to prosecute your ass for something, anything — “losing a war” wasn’t a crime in itself, but whatever the official charge (usually “corruption” or “misuse of public funds” or something), everyone knew you were really getting punished for losing.

At no point, however, did the putative justification for war come into play. Picking a war with the Parthians wasn’t bad in itself. Nor was “picking a war with the Parthians because you gots to get paid”. Certainly picking a war with, say, the Gauls wasn’t bad in itself, and “picking a war with the Gauls because I need to capture and sell a few thousand slaves to cover my debts” was so far from being bad, guys like Caesar, if I recall my Gallic Wars correctly, openly declared it from jump street. And though Caesar surely would’ve been prosecuted if he’d lost, and Crassus if he’d lived, suggesting that anyone owed an apology to the Gauls or Parthians would’ve gotten you locked up as a dangerous lunatic.

A confident, manly power might lose a war or two. Hell, they might lose a bunch — the Romans got beat all the time, and so did the British. But no matter how bad the loss, or how embarrassing the peace treaty, they shrugged it off. You win some, you lose some, and when it’s clear you’re going to lose — or when it becomes clear that there’s no possible way “victory” will ever be worth the cost — you cut your losses and came home. HM forces, for instance, lost no less than three wars in Afghanistan. And so what? Great Britain was still the world’s preeminent power. They never even dreamed of apologizing — that’s the Great Game, old sock.

Severian, “Friday Mailbag / Grab Bag”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-07-23.

April 29, 2024

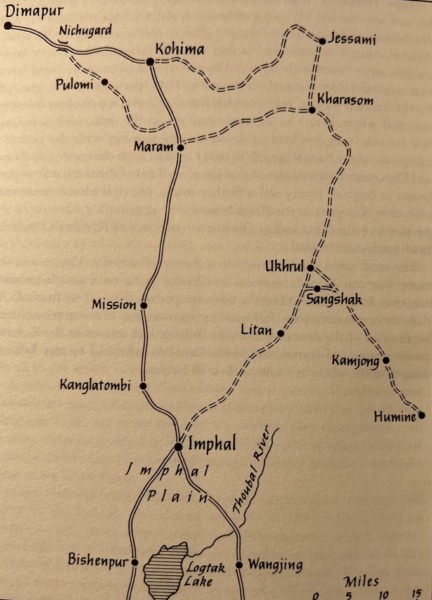

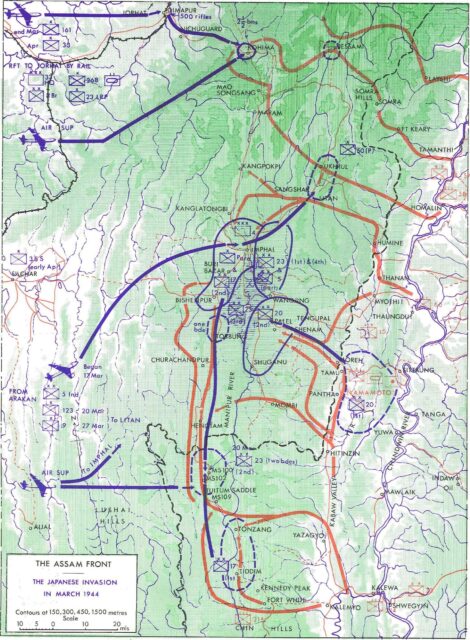

“The disaster at Imphal was perhaps the worst of its kind yet chronicled in the annals of war”

Dr. Robert Lyman makes the case for the Japanese defeat at the battles of Imphal and Kohima being one of the four great turning points in the Second World War:

It is clear to me that the great twin battle of Imphal & Kohima, which raged from March through to late July 1944, was one of four great turning-point battles in the Second World War, when the tide of war changed irreversibly and dramatically against those who initially held the upper hand.

The first great turning point was arguably at Midway in June 1942 when the US Navy successfully challenged Japanese dominance in the Pacific. The second was at Stalingrad between August 1942 and January 1943 when the seemingly unstoppable German juggernaut in the Soviet Union was finally halted in the winter bloodbath of that city, where only 94,000 of the original 300,000 German, Rumanian and Hungarian troops survived. The third was at El Alamein in October 1942 when the British Commonwealth triumphed against Rommel’s Afrika Korps in North Africa and began the process that led to the German surrender in Tunisia in May 1943. The fourth was this battle, that at Kohima and Imphal between March and July 1944 when the Japanese “March on Delhi” was brought to nothing at a huge cost in human life, and the start of their retreat from Asia began. Adjectives such as “climactic” and “titanic”, struggle to give proper impact to the reality and extent of the terrible war that raged across the jungle-clad hills during these fearsome months.

That the Japanese were contemplating an offensive against India in early 1944 was a surprise to Allied planners, who had given no thought to its possibility. By this time Japan had reached the apogee of its power, having extended the violent reach of its Empire across much of Asia since it launched its first surprise attacks in late 1941. Its initial surge in 1942 into what was briefly to be Japan’s “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” was as dramatic as it was rapid and two years further on several millions of peoples across Asia laboured under its heavy yoke. But by early 1944 the tide had turned decisively in the Pacific, the American island-hopping advance reaching steadily but surely towards Japan itself, its humiliated enemies fighting back with desperation, and with every ounce of energy they could muster. They were beginning to prevail in the fight although the struggle on the landmass of Asia was a strategic sideshow in the context of a global conflict: at this time the British and American High Commands were totally occupied with Europe and the Pacific. The British and Americans were preparing for D Day. The Soviets were advancing in Ukraine. There was a stalemate in Italy at Monte Cassino. The Americans were preparing to land in the Philippines. Germany and Japan were both in retreat, but not defeated. In this global context India and Burma appeared strategically peripheral, even inconsequential. Yet in this month, at a time when on every other front the Japanese were on the strategic defensive, Japan launched a vast, audacious offensive deep into India in an attack designed to destroy for ever Britain’s ability to challenge Japan’s hegemony in Burma.

The Japanese commander was General Mutaguchi Renya, a gutsy go-getter who had played a significant role in the collapse of Singapore in February 1942. His evaluation of the British position in northeast India revealed that the three key strategic targets in Assam and Manipur were Imphal; the mountain town of Kohima, and the huge supply base further back on the edge of the Brahmaputra Valley at Dimapur. If Kohima were captured, Imphal would be cut off from the rest of India by land. From the outset Mutaguchi believed that with a good wind Dimapur, in addition to Kohima, could and should be secured. He reasoned that capturing this massive depot would be a devastating, possibly terminal blow to the British ability to defend Imphal, supply the Americans in Northern Burma under Vinegar Joe Stilwell, support the Hump airlift into China and mount an offensive into Burma. It would also enable him to feed his own, conquering army, which would advance across the mountains from the Chindwin on the tightest imaginable supply chain. With Dimapur captured, the Japanese-led Indian National Army under the Bengali nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose could pour into Bengal, initiating the long-awaited anti-British uprising.

The essence of the battle for India in 1944 can be quickly told. Mutaguchi’s 15th Army advanced in four separate columns into Manipur. The Japanese made determined, even desperate, efforts to seize their objectives: in the north Kohima, with a scratch British and Indian garrison of 1,200 trained fighting soldiers – about two thirds of them Indian – was attacked by an entire division of about 15,000 men in early April. Surrounded and slowly forced back onto a single hill they were supplied by air until relief came on 20 April, although the battle to dislodge the Japanese from Kohima continued bloodily, in appalling weather and battlefield conditions – the annual monsoon was in full spate – through to early June. Further south the Japanese plan entailed attacking Imphal from north, east and south. The plan of the commander of the 14th Army, Lieutenant General Bill Slim, was to withdraw his forces into the hills and there to allow the Japanese to expend themselves fruitlessly against well-supplied and aggressive British bastions, equipped with tanks, artillery and supported by air. The battle for Imphal in Manipur and for Kohima to the north-west in the neighbouring Naga Hills settled down to a bloody hand-to-hand struggle as the Japanese tried to gain the foothold necessary for their survival. They travelled lightly, and reserves soon exhausted themselves and further supplies were almost non-existent. Just as the air situation was becoming critical for Slim through poor weather and shortages of aircraft the relieving division from Kohima – the British 2nd Infantry Division that had last seen action at Dunkirk – began fighting its way towards Imphal, and the four beleaguered divisions began to push out from the Imphal pocket. By 22 June the 2nd Division and the 5th Indian Division met north of Imphal and the road to the plain was open. Four weeks later the Japanese withdrawal to Burma began.

Of all the invading armies of history, it is hard to think of one that was repulsed more decisively, or more ignominiously, than the Japanese 15th Army launched against India in March 1944. Its defeat was not the fault of the Japanese soldiers, who fought courageously, tenaciously and fiercely, but of their commanders, who sacrificed the lives of their troops on the altar of their own hubris. The battle had provided the largest, most prolonged and most intense engagement with a Japanese army yet seen in the war. “It is the most important defeat the Japs have ever suffered in their military career” wrote Mountbatten exultantly to his wife on 22nd June 1944, “because the numbers involved are so much greater than any Pacific Island operation.” The extent of the disaster that befell the 15th Army is captured by a comment by Kase Toshikazu, a member of the wartime Japanese Foreign Office, who lamented: “Most of this force perished in battle or later of starvation. The disaster at Imphal was perhaps the worst of its kind yet chronicled in the annals of war.” The latter might better have included the caveat “Japanese” to avoid charges of exaggeration, but his comment captures something of the enormity of the human disaster that overwhelmed the 15th Army. It might more fairly be described as the greatest Japanese military disaster of all time. The Indian, Gurkha, African and British troops of this remarkably homogeneous organisation had also decisively removed any remaining notions of Japanese superiority on the battlefield.

The importance of this victory was overshadowed at the time, and downplayed for decades afterwards, by the massive victories in 1945 which brought World War II to an end in Europe and the Pacific. But this lack of publicity and of awareness does not remove the fact that, objectively speaking, the battles in India in 1944, epitomized in the fulcrum battle at Kohima, were an epic comparable with Thermopylae, Gallipoli, Stalingrad, and other better known confrontational battles where the arrogant invader became, in time, the ignominious loser.

Greek History and Civilization, Part 7 – Alexander

seangabb

Published Apr 28, 2024This seventh lecture in the course covers the career of Alexander the Great and its consequences for the world.

(more…)

“The Earth goes around the Sun, or so they would have you believe …”

Colby Cosh on a recent “grand theory” from Andrea Matranga, an Italian economist who outlined his thoughts in a paper accepted by the Quarterly Journal of Economics, summarized in the sub-hed “Hunter-gatherers were better off than Neolithic farmers, diet-wise — until Earth was hit by seasonal extremes caused by Jupiter’s gravity”:

Reconstruction of a neolithic farmstead at the Irish National Heritage Park in Ferrycarrig.

Photo by Jo Turner via Wikimedia Commons.

Matranga’s own explanation for the invention of agriculture is: “Believe it or not, it is down to extraterrestrial forces”. Yes, that’s an actual quote from a cheeky Twitter thread in which Matranga summarizes his hypothesis colourfully. The real idea is that the period of the Neolithic Revolutions coincided with a time when seasonal temperature and rainfall differences were maximized by coinciding features of Earth’s orbit — features attributable mostly to Jupiter’s gravitational tug on us.

The Earth goes around the Sun, or so they would have you believe, and Earth’s rotational axis is tilted relative to the Sun, which creates the seasons. But the Earth’s motion has other subtle wobbles and shimmies caused by Jupiter: the eccentricity of its elliptical orbit grows and shrinks, and the rotational axis “precesses”, or wobbles, meaning that the face of the Earth pointing toward the Sun at our closest approach to it changes over time.

The implication of this is that over a period of millennia, and particularly in what we think of as the “temperate” zones, the magnitude of climate seasonality will itself change in a somewhat chaotic way. For some periods much longer than a human lifetime, seasonal changes might be almost beneath notice; a few millennia later, they become a dominant feature of human experience. And one hemisphere of the planet — say, the northern one — might end up with a lingering developmental advantage because it was favoured at the right moment by the precession of Earth’s axis.

Matranga pulls together a lot of math, astronomy and geography to show that the local Neolithic Revolutions coincide with maximum local seasonality, and then he builds some economic models of primitive society to suggest what effect this might have had on social organization and population evolution. Alfred Marshall would have told him to burn this part of his paper, but perhaps the equations are necessary for appearances. The crucial point is that Matranga has found a strong possible explanation for the Neolithic paradox — why, and when, humans in many places adopted a form of social organization that seems to have left most of them worse off on average.

For it’s not just the average that matters. In a world that was more or less the same year-round, hunter-gatherers didn’t have to worry about food storage: they could migrate cyclically within a small range, following wild game, to keep up with modest seasonal effects. But if the seasons then got more intense, food storage would become more important to the long-term survival of the group: one winter could now finish everyone off.

Battle Rifles of World War Two: Overview

Forgotten Weapons

Published Jan 26, 2024Today we are going to take a look at the three main battle rifles of World War Two — the M1 Garand, the SVT-40, and the Gewehr 43. We will also consider the SVT-38, Gewehr 41(W), and Gewehr 41(M). The United States, Soviet Union, and Germany were the three countries that fielded large numbers of semiautomatic full-power rifles in combat in WW2; how did they differ in their approaches to infantry firepower?

(more…)