So who are our [academic] combatants? To understand this, we have to lay out a bit of the “history of the history” – what is called historiography in technical parlance. Here I am also going to note the rather artificial but importance field distinction here between ancient (Mediterranean) history and medieval European history. As we’ll see, viewing this as the end of the Roman period gives quite a different impression than viewing it as the beginning of a new European Middle Ages. The two fields “connect” in Late Antiquity (the term for this transitional period, broadly the 4th to 8th centuries), but most programs and publications are either ancient or medieval and where scholars hail from can lead to different (not bad, different) perspectives.

So who are our [academic] combatants? To understand this, we have to lay out a bit of the “history of the history” – what is called historiography in technical parlance. Here I am also going to note the rather artificial but importance field distinction here between ancient (Mediterranean) history and medieval European history. As we’ll see, viewing this as the end of the Roman period gives quite a different impression than viewing it as the beginning of a new European Middle Ages. The two fields “connect” in Late Antiquity (the term for this transitional period, broadly the 4th to 8th centuries), but most programs and publications are either ancient or medieval and where scholars hail from can lead to different (not bad, different) perspectives.

With that out of the way, the old view, that of Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) and indeed largely the view of the sources themselves, was that the disintegration of the western half of the Roman polity was an unmitigated catastrophe, a view that held largely unchallenged into the last century; Gibbon’s great work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1789) gives this school its name, “decline and fall“. While I am going at points to gesture to Gibbon’s thinking, we’re not going to debate him; he is the “old man” of our title. Gibbon himself largely exists only in historiographical footnotes and intellectual histories; he is not at this point seriously defended nor seriously attacked but discussed as the venerable, but now out of date, origin point for all of this bickering.

The real break with that view came with the work of Peter Brown, initially in his The World of Late Antiquity (1971) and more or less canonically in The Rise of Western Christendom (1st ed. 1996; 2nd ed. 2003, 3rd ed. 2013). The normal way to refer to the Peter Brown school of thought is “change and continuity” (in contrast to the traditional “decline and fall”), though I rather like James O’Donnell’s description of it as the Reformation in late antique studies.

Among medievalists this reformed view, which focuses on continuity of culture and institutions from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages, remains essentially the orthodoxy, to the point that, for instance, the very recent (and quite excellent) The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe (2021) can present this vision as an uncomplicated fact, describing the “so-called Fall of Rome” and noting that “there was never a moment in the next thousand years in which at least one European or Mediterranean ruler didn’t claim political legitimacy through a credible connection to the empire of the Romans” and that “the idea that Rome ‘fell’ on the other hand, relies upon a conception of homogeneity – of historical stasis … things changed. But things always change” (3-4, 12-3). As we’ll see, I don’t entirely disagree with those statements, but they are absolute to a degree that suggests there is no real challenge to the position. There have been a few cracks in this orthodoxy among medievalists, particularly the work of Robin Flemming (a revision, not a clear break, to be sure), to which we’ll return, but the cracks have been relatively few.

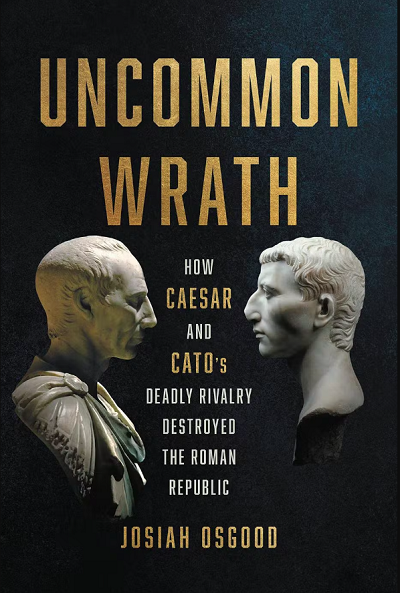

While some ancient historians also bought into this view, purchase there has always been uneven and seems, to me at least, now to be waning further. Instead, a process of what James O’Donnell describes as a “counter-reformation” (which he stoutly resists with his own The Ruin of the Roman Empire; O’Donnell is a declared reformer) is well underway, a response to the “change and continuity” narrative which seeks to update and defend the notion that there really was a fall of Rome and that it really was quite bad actually. This is not, I should note, an effort to revive Gibbon per se; it does not typically accept his understanding of the cause of this decline (and often characterizes exactly what is declining differently). Nevertheless, this position too is sometimes termed the “decline and fall” school. My own sense of the field is that while nearly all ancient historians will feel the need to concede at least some validity to the reformed “change and continuity” vision, that the counter-reformation school is the majority view among ancient historians at this point (in a way that is particularly evident in overview treatments like textbooks or the Cambridge Ancient History (second edition)). We’ll meet many of the core works of this revised “decline and fall” school as we go.

As O’Donnell noted in a 2005 review for the BMCR, the reformed school tends to be strongest in the study of the imperial east rather than the west (something that will make a lot of sense in a moment), and in religious and cultural history; the counter-reformation school is stronger in the west than the east and in military and political history, though as we’ll see, to that list must at this point now be added archaeology along with demographic and economic history, at which point the weight of fields tends to get more than a little lopsided.

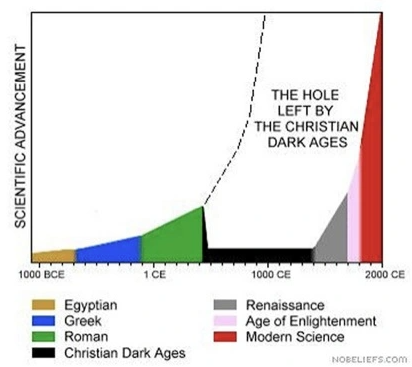

Those are our two knights – the “change and continuity” knight and the “decline and fall” knight (and our old man Gibbon, long out of his dueling days). To this we must add the nitwit: a popular vision, held by functionally no modern scholars, which represents the Middle Ages in their entirety as a retreat from a position of progress during the Roman period which was only regained during the “Renaissance” (generally represented as a distinct period from the Middle Ages) which then proceeded into the upward trajectory of the early modern period. Intellectually, this vision traces back to what Renaissance thinkers thought about themselves and their own disdain for “medieval” scholastic thinking (that is, to be clear, the thinking of their older teachers), a late Medieval version of “this ain’t your daddy’s rock and roll!”

But almost every intellectual movement represents itself as a radical break with the past (including, amusingly, many of the scholastics! Let me tell you about Peter Abelard sometime); as historians we do not generally accept such claims uncritically at face value. For a long time, well into the 19th century, the Renaissance’s cultural cachet in Europe (and the cachet of the classical period where it drew its inspiration) shielded that Renaissance claim from critique; that patina now having worn thin, most scholars now reject it, positioning the Renaissance as a continuation (with variations on the theme) of the Middle Ages, a smooth transition rather than a hard break. At the same time, knowledge of developments within the Middle Ages have made the image of one unbroken “Dark Age” untenable and made clear that the “upswing” of the early modern period was already well underway in the later Middle Ages and in turn had its roots stretching even deeper into the period. It is also worth noting here, that the term “Dark Age” has to do with the survival of evidence, not living conditions: the age was not dark because it was grim, it was dark because we cannot see it as clearly.

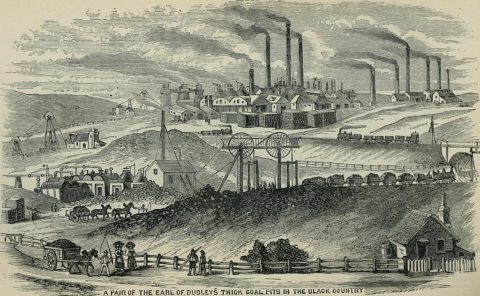

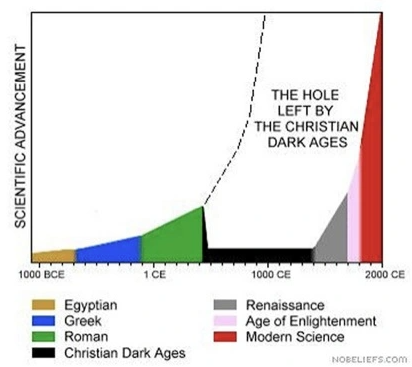

The popular version of this idea continues, however, to have a lot of sway in the popular conception of the Middle Ages, encouraged by popular culture that mistakes the excesses of the early modern period for “medieval” superstition and exaggerates the poverty of the medieval period (itself essentialized to its worst elements despite being approximately a millennia long), all summed up in this graph:

We are mostly going to just dunk relentlessly on this graph and yet we will not cover even half of the necessary dunking this graph demands. We may begin by noting that in its last century, the Roman Empire was Christian, a point apparently missed here.

While that sort of vision is not seriously debated by scholars, it needs to be addressed here too, in part because I suspect a lot of the energy behind the “change and continuity” position is in fact to counter some of the worst excesses of this thesis, which for simplicity, we’ll just refer to as “The Dung Ages” argument, but also because assessing how bad the fall of the Roman Empire in the West was demands that we consider how long-lasting any negative ramifications were.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Rome: Decline and Fall? Part I: Words”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-01-14.