Why, despite China’s prodigious lead in science, technology, population, and economic activity, did the scientific revolution and then the industrial revolution happen in Europe? Why did they fall so far behind after being so far ahead?

There are all kinds of answers given to this question, from ones based around the concept of “agricultural involution” (which I briefly surveyed in my review of Energy and Civilization), to ones that blame the complexity of the Chinese system of writing and other more outlandish theories. But would you know it, this question is commonly referred to within Sinology as the “Needham puzzle” or the “Needham question”, so what does the man himself think? Needham got the credit for posing the question, not for answering it, but in the final chapter of this book, “Attitudes Towards Time and Change”, he drops some fascinating hints.

A belief common to the great civilizations of the Axial Age was that time itself was somehow unreal. Greek philosophers from the pre-Socratics to the Neo-Platonists all expressed it in very different ways, but all agreed that in some sense the world of mutability and change was an illusion, and that outside of it stood an eternal, absolute reality sufficient in itself, unchanging in its perfection, αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων. The Buddhist civilizations include this under the doctrine of maya (illusion), and traditional Hinduism also exhibits time as a dreamlike and incidental quality of the world.

If time is somehow unreal and nothing can ever change, then it’s easy to see the attraction of a cyclic conception of history. And indeed, in the ancient world these cyclic theories predominate. The Babylonians had their Great Year, and Greek thinkers as diverse as Hesiod, Pythagoras, Plato, and Aristotle all speculated about the eternal repetition and recurrence of the ages of the world. In the Mahabharata the great yugas and kalpas, the Days of Brahma, follow one another in an inevitable fourfold cycle of world ages, the profusion of Hindu and Buddhist sects have promulgated a thousand interpretations and variations on this basic pattern. On the other side of the world, the Mayans had their own Great Year, and countless other peoples besides. This cosmology almost feels like a human universal (at least for civilizations at a particular stage of development), and why wouldn’t it be? We open our eyes and all we see are cycles within cycles — the cycle of the day, the cycle of the moon, the cycle of the seasons, the cycle of the generations. As sure as day follows night, why wouldn’t we expect that the universe too, a grand mechanism made by the gods, must eventually return to its starting point.

Various philosophers of science have asserted that this view of history makes scientific progress impossible, because of its fatalism and pessimism. If everything that happens has happened before and will happen again, then why bother trying to change anything? It’ll just get undone in the Kali Yuga anyway. But Needham points out another connection: if time is cyclic, or worse yet somehow unreal, then it makes no sense to stretch it out into an independent coordinate. In this way, the entire metaphysics of cyclical time resists the mathematization of physics. One can imagine the analytic geometry of Descartes being discovered in ancient Alexandria or Tikal or Harappa, but would it have been possible for one of the coordinate axes to represent time? A Descartes was possible, but a Newton or a Bernoulli was inconceivable.

All of this changes with the advent of Christianity, for which the most important fact about the world, the Incarnation, takes place at a particular moment in history, once and for all, κατὰ πάντα καὶ διὰ πάντα. The cosmos is fixed around this central point, and cannot curl back upon itself. Kairos transfigures chronos, and in so doing makes it real, gives it force and meaning. History is not a cycle, but a story of creation, separation, incarnation, and redemption, speeding towards its culmination as assuredly as a stone tracing a parabolic arc through the air. Or as Needham puts it:

[In the Indo-Hellenic world] space predominates over time, for time is cyclical and eternal, so that the temporal world is much less real than the world of timeless forms, and indeed has no ultimate value … The world eras go down to destruction one after the other, and the most appropriate religion is therefore either polytheism, the deification of particular spaces, or pantheism, the deification of all space … For the Judaeo-Christian, on the other hand, time predominates over space, for its movement is directed and meaningful … True being is immanent in becoming, and salvation is for the community in and through history. The world era is fixed upon a central point which gives meaning to the entire process, overcoming any self-destructive trend and creating something new which cannot be frustrated by cycles of time.

Some historians of science have argued that without this linear conception of time introduced by Christianity, we lack the conceptual vocabulary for various things ranging from analytic methods in physics to the idea of causality itself. So is that the answer? Is the solution to the Needham Puzzle that China progressed as far as it could until, weighed down by the fatalism of cyclic history and the impoverished mathematical vocabulary of timeless metaphysics, it ground to a halt?

Unfortunately, the answer is no. This theory sounds great, but it’s totally wrong.

There’s a bad habit among Western historians and philosophers of engaging in a shallow sort of Orientalism that aggregates all of the exotic East into a single entity.1 But when it comes to attitudes towards time, change, and history; the traditional Chinese attitude is much closer to that of Christendom than it is to the Hindu or Buddhist view. Needham does a good job summarizing the basic Chinese outlook, but includes a lot of details I didn’t know, including that the view of civilizations as ascending through distinct historical stages (e.g. the Stone Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age, etc.) is of Chinese origin! Needham also discusses the veneration, sometimes deification, of great inventors that saturates Chinese folk religion. All in all, the picture is one of China as a progress-obsessed society almost from its earliest moments, and as a society that was steadily progressing right up until it was suddenly and dramatically eclipsed by European science.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: Science in Traditional China, by Joseph Needham”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-08-14.

1. I am infuriated by restaurants that advertise “Asian food”. There’s more culinary diversity inside some regions of China than there is in most of Europe.

October 10, 2024

QotD: Why did ancient China lose its early lead in science and technology?

October 6, 2024

Look at Life – The Big Takeoff (1966)

Classic Vehicle Channel

Published Apr 19, 2020The 1966 airshow. Prince Phillip attends via helicopter.

October 4, 2024

You know the jig is up for “renewables” when even Silicon Valley techbros turn against it

JoNova on the remarkably quick change of opinion among the big tech companies on the whole renewable energy question:

Google, Oracle, Microsoft were all raving fans of renewable energy, but all of them have given up trying to reach “net zero” with wind and solar power. In the rush to feed the baby AI gargoyle, instead of lining the streets with wind turbines and battery packs, they’re all suddenly buying, building and talking about nuclear power. For some reason, when running $100 billion dollar data centres, no one seems to want to use random electricity and turn them on and off when the wind stops. Probably because without electricity AI is a dumb rock.

In a sense, AI is a form of energy. The guy with the biggest gigawatts has a head start, and the guy with unreliable generators isn’t in the race.

It’s all turned on a dime. It was only in May that Microsoft was making the “biggest ever renewable energy agreement” in order to power AI and be carbon neutral. Ten minutes later and it’s resurrecting the old Three Mile Island nuclear plant. Lucky Americans don’t blow up their old power plants.

Oracle is building the world’s largest datacentre and wants to power it with three small modular reactors. Amazon Web Services has bought a data centre next to a nuclear plant, and is running job ads for a nuclear engineer. Recently, Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai, spoke about small modular reactors. The chief of Open AI also happens to chair the boards of two nuclear start-ups.

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

QotD: Compound eyes as models of how the surveillance state operates

Compound eyes, common with insects and crustaceans, are made up of thousands of individual visual receptors, called ommatidia. Each ommatidium is a fully functioning eye in itself. The insect’s “eye” is thousands of ommatidium that together create a broad field of vision. Every ommatidium has its own nerve fiber connecting to the optic nerve, which relays information to the brain. The brain then processes these inputs to create a three-dimensional understanding the surrounding space.

The compound eye is a good way to imagine how the surveillance state will keep tabs on the subjects in the near future. Unlike the dystopian future imagined by science fiction, it will not be one eye focusing on one heretic, following him around as he goes about his business. Instead it will be tens of millions of eyes obtaining various bits of information, sending it back to the data-centers run by Big Tech. That information will be assembled into the broad mosaic that is daily life.

For example, rather than use informants and undercover operatives to flesh out conspiracies against the state, the surveillance state will use community detection to model the network of heretics. Since everyone is hooked into the grid in some fashion and everyone addresses nodes of the grid on a regular basis, keeping track of someone is now something that can be done from a cubicle. There is no need to actually follow someone around as they go about their life.

For example, everyone has a mobile phone. At every point, the phone is tracking its location, which means it is tracking your location. It also knows the time and day when you go into various businesses. Most people use cards to pay miscellaneous items, so just that information would tell the curious a lot about you. Combine that information with the same information from other phones that come into close proximity with your phone and figuring out the community structure is simple.

Of course, the mobile phone is not the only input device. Over Christmas, millions of Americans were encouraged to install surveillance devices in their homes by friends and family. Maybe it was an Alexa listening device from Amazon or a Nest Doorbell surveillance device from Google. All of these gadgets are collecting data on your life inside and around your home. It is then fed to the same data-centers that have all of your movements and associations collected from your phone.

The Z Man, “The Compound Eye”, The Z Blog, 2020-01-08.

September 29, 2024

This Bridge Should Have Been Closed Years Before It Collapsed

Practical Engineering

Published Jun 18, 2024Why Fern Hollow Bridge collapsed.

This is a crazy case study of how common sense can fall through the cracks of strained budgets and rigid oversight from federal, state, and city staff. And the lessons that came out of it aren’t just relevant to people who work on bridges. It’s a story of how numerous small mistakes by individuals can collectively lead to a tragedy.

(more…)

September 21, 2024

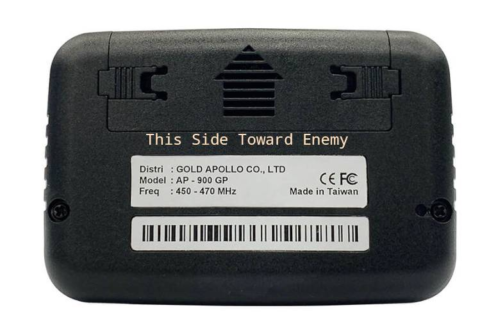

“This might be the greatest asymmetrical attack in human history”

Terrorist organizations in the Middle East always have to be aware of the risk of coming to the attention of Israel accidentally, and they’ve suffered losses whenever their operations have been prematurely exposed. The attack on Hezbollah’s communications infrastructure is, as Phil A. McBride says in The Line, “something genuinely new in warfare”:

The attack on Hezbollah’s communications through exploding pagers, radios, and other electronic devices triggered a cascade of instant memes.

Detonating the pagers and other devices would have been a relatively easy thing to do (to the extent that any of this was easy!), since it’s obvious that Israel had already penetrated the pager network, and Hezbollah’s communications generally, before the devices were even deployed. Once Israel was confident that they’d put all the devices into the right hands, they simply sent a message — remember, these devices are all intended to receive telecommunications — that somehow triggered the explosions we saw. I don’t know if the explosives did all the damage, or if the batteries were somehow overloaded as well. What is clear is that the explosions were enough to kill, injure and maim people who were directly holding the devices, but not much more. Videos posted online show people suddenly dropping to the ground in agony after their device explodes in their hands, pockets or backpacks, but people in their immediate vicinity are unharmed.

Again, none of this is easy, but if one is looking to remotely detonate a bomb, it helps when the bomb it intended to literally receive incoming communications.

[…]

That covers the pagers and two-way radios, but what about the other various items that exploded? While almost everything electronic you can buy these days has internet/wireless capability, Hezbollah went through a lot of trouble to be as disconnected from the internet as possible. I can only assume they wouldn’t have connected a device meant to read the fingerprints of terrorists trying to enter a safe house to the internet, where a Mossad hack is a constant threat. This means that any other device that exploded not only had explosive charges installed, but also a radio capable of receiving a remote detonation command. The most efficient approach would have been to tune those radios to the same frequencies used by Hezbollah’s two-way radios to minimize the infrastructure needed to pull off what was already an insanely complex operation, but we will need more information to even begin to understand that part of Israel’s plan.

And let’s talk about the plan. The level of sophistication for such an operation cannot be understated. Everything that we’ve seen over the last few days indicates a complete and total breakdown of Hezbollah’s internal security. Israel managed to intercept and infiltrate both their primary and backup communications networks before they were even deployed, as well as a swath of other electronic equipment, and turn them into bombs.

It has been said that communication is the most important component of any military system, but I don’t think anyone had ever thought of actually weaponizing the opposition’s communications infrastructure itself before now. This is something genuinely new in warfare.

September 20, 2024

The Me163 Komet – Rockets Are Dangerous

HardThrasher

Published Jun 3, 2024The story of the Me163 is a complex and multifaceted one, and I have attempted here to draw together a number of different sources into a narrative covering the political, structural, scientific and operational history. Necessarily I will have missed things and probably got things wrong. Where I know a mistake has been made, you’ll find it in the pinned comment marked “snagging” – one obvious example is Winkle Brown flew a “sharp” start after the war ended on an Me163 in Germany, and a towed flight in the UK, which I missed.

The below then is an extremely limited subset of the resources I’ve pulled on:

Me163 Rocket Interceptor – Stephen Ransom and Hans-Herman Cammann – not for the faint of heart, a book with brilliant nuggets, a drunken editor and a lot of very pretty pictures. This was my primary source.

Rocket Fighter – Marno Ziggler – Now out of print, this is a Hitler Jugend‘s Own Adventure story most of which has some truth in it but a lot of which is Marno wishing to be in his early 20s and flying for the Führer again. You can find it online fairly easily.

The kids probably haven’t got a clue what a video tape is, never mind Betamax https://legacybox.com/blogs/analog/vh… – Betamax vs VHS

Baxter, AD: Walter Rocket Motors for Aircraft, RAE Technote Aero 1668, September 1945 – a Technical note that’s incredibly hard to get hold of, but which I managed to find, quite by chance, in some papers I got years ago. Probably available from the UK National Archives still.

http://www.walterwerke.co.uk/walter/i… – a fantastic archive of all things Walter but it isn’t an https site as a warning.

https://hushkit.net/2019/03/29/the-li… – The coal powered bomber rammer P.13

https://donhollway.com/me-163/ – Bat out of Hell – great website for images of the Me163 as imagined in the Artists’ fever dreams

WW2 Gun Camera: 8th Air Force VS Mess… – Gun Cam Footage of the Me163 and Me262s being shot at and down by various USAAF pilots.

https://airandspace.si.edu/collection… – Air and Space Museum have their usual, brilliant photos and terrible descriptions.

September 19, 2024

“This is the Law of Unintended Consequences in action”

Tom Knighton provides a wonderful example of “be careful what you wish for”, especially in the rich virtue-signal territory of the “green transformation”:

“Artisanal cobalt miners in the Democratic Republic of Congo” by The International Institute for Environment and Development is licensed under CC BY 2.5 .

… it seems our glorious green future now comes with more child labor!

A new report from the Department of Labor raises tough questions about whether and to what extent forced labor and child labor are intertwined with climate-friendly technology.

The department released a report this month finding that several minerals that are key components of electric vehicles and solar panels may be produced through these unethical labor practices.

The findings point to major ethical quandaries surrounding the ongoing energy transition. Climate change, if not addressed, endangers many of the world’s most vulnerable people. At the same time, the report raises serious human rights concerns about the technology being used to address it.

[…]

Whoops.Here’s the thing, cobalt and nickel are kind of important for this sort of thing, so we have to get them from somewhere and the one attempt to mine cobalt here in the United States fell flat. Why? The price of cobalt dropped. It was no longer profitable to try to mine it in the United States.

But in poor countries, it was still plenty viable.

Yet while we view child labor as unethical, we have to remember that our society is rich enough that we can afford to hold that belief. Now, I share it and I’d rather kids be kids, and worry about things like school, video games, television, and that sort of thing, but the truth is that when you’re barely able to feed yourself, you need every penny you can get.

That means kids going out to work.

That means doing some grueling, back-breaking, nasty work like mining stuff like cobalt.

It means paying for dirty, nasty strip mining so you can convince yourself and your friends that you’re better than those of us who still prefer a gasoline- or diesel-powered car.

All around us, we tend to be oblivious to the reality of the rest of the world. We simply think something should be so and then just act like they are. We ignore what all might be required to make that something so.

This is the Law of Unintended Consequences in action.

September 16, 2024

Stephen Fry on artificial intelligence

On his Substack, Stephen Fry has posted the text of remarks he made last week in a speech for King’s College London’s Digital Futures Institute:

So many questions. The first and perhaps the most urgent is … by what right do I stand before you and presume to lecture an already distinguished and knowledgeable crowd on the subject of Ai and its meaning, its bright promise and/or/exclusiveOR its dark threat? Well, perhaps by no greater right than anyone else, but no lesser. We’ll come to whose voices are the most worthy of attention later.

I have been interested in the subject of Artificial Intelligence since around the mid-80s when I was fortunate enough to encounter the so-called father of Ai, Marvin Minsky and to read his book The Society of Mind. Intrigued, I devoured as much as I could on the subject, learning about the expert systems and “bundles of agency” that were the vogue then, and I have followed the subject with enthusiasm and gaping wonder ever since. But, I promise you, that makes me neither expert, sage nor oracle. For if you are preparing yourselves to hear wisdom, to witness and receive insight this evening, to bask and bathe in the light of prophecy, clarity and truth, then it grieves me to tell you that you have come to the wrong shop. You will find little of that here, for you must know that you are being addressed this evening by nothing more than an ingenuous simpleton, a naive fool, a ninny-hammer, an addle-pated oaf, a dunce, a dullard and a double-dyed dolt. But before you streak for the exit, bear in mind that so are we all, all of us bird-brained half-wits when it comes to this subject, no matter what our degrees, doctorates and decades of experience. I can perhaps congratulate myself, or at least console myself, with the fact that I am at least aware of my idiocy. This is not fake modesty designed to make me come across as a Socrates. But that great Athenian did teach us that our first step to wisdom is to realise and confront our folly.

I’ll come to the proof of how and why I am so boneheaded in a moment, but before I go any further I’d like to paint some pictures. Think of them as tableaux vivants played onto a screen at the back of your mind. We’ll return to them from time to time. Of course I could have generated these images from Midjourney or Dall-E or similar and projected them behind me, but the small window of time in which it was amusing and instructive for speakers to use Ai as an entertaining trick for talks concerning Ai has thankfully closed. You’re actually going to have to use your brain’s own generative latent diffusion skills to summon these images.

[…]

An important and relevant point is this: it wasn’t so much the genius of Benz that created the internal combustion engine, as that of Vladimir Shukhov. In 1892, the Russian chemical engineer found a way of cracking and refining the spectrum of crude oil from methane to tar yielding amongst other useful products, gasoline. It was just three years after that that Benz’s contraption spluttered into life. Germans, in a bow to this, still call petrol Benzin. John D. Rockefeller built his refineries and surprisingly quickly there was plentiful fuel and an infrastructure to rival the stables and coaching inns; the grateful horse meanwhile could be happily retired to gymkhanas, polo and royal processions.

Benz’s contemporary Alexander Graham Bell once said of his invention, the telephone, “I don’t think I am being overconfident when I say that I truly believe that one day there will be a telephone in every town in America”. And I expect you all heard that Thomas Watson, the founding father of IBM, predicted that there might in the future be a world market for perhaps five digital computers.

Well, that story of Thomas Watson ever saying such a thing is almost certainly apocryphal. There’s no reliable record of it. Ditto the Alexander Graham Bell remark. But they circulate for a reason. The Italians have a phrase for that: se non e vero, e ben trovato. “If it’s not true, it’s well founded.” Those stories, like my scenario of that group of early investors and journalists clustering about the first motorcar, illustrate an important truth: that we are decidedly hopeless at guessing where technology is going to take us and what it’ll do to us.

You might adduce as a counterargument Gordon Moore of Intel expounding in 1965 his prediction that semiconductor design and manufacture would develop in such a way that every eighteen months or so they would be able to double the number of transistors that could fit in the same space on a microchip. “He got that right,” you might say, “Moore’s Law came true. He saw the future.” Yes … but. Where and when did Gordon Moore foresee Facebook, TikTok, YouTube, Bit Coin, OnlyFans and the Dark Web? It’s one thing to predict how technology changes, but quite another to predict how it changes us.

Technology is a verb, not a noun. It is a constant process, not a settled entity. It is what the philosopher-poet T. E. Hulme called a concrete flux of interpenetrating intensities; like a river it is ever cutting new banks, isolating new oxbow lakes, flooding new fields. And as far as the Thames of Artificial Intelligence is concerned, we are still in Gloucestershire, still a rivulet not yet a river. Very soon we will be asking round the dinner table, “Who remembers ChatGPT?” and everyone will laugh. Older people will add memories of dot matrix printers and SMS texting on the Nokia 3310. We’ll shake our heads in patronising wonder at the past and its primitive clunkiness. “How advanced it all seemed at the time …”

Those of us who can kindly be designated early adopters and less kindly called suckers remember those pioneering days with affection. The young internet was the All-Gifted, which in Greek is Pandora. Pandora in myth was sent down to earth having been given by the gods all the talents. Likewise the Pandora internet: a glorious compendium of public museum, library, gallery, theatre, concert hall, park, playground, sports field, post office and meeting hall.

September 10, 2024

“The world has gone mad. But nothing is as crazy as the AI news”

Ted Gioia is covering the AI beat like nobody else. In this post he shares several near-term predictions involving AI development and deployment:

The world has gone mad. But nothing is as crazy as the AI news.

Every day those AI bots and their human posse of true believers get wilder and bolder — and recently they’ve been flexing like body builders on Muscle Beach.

The results are sometimes hard to believe. But all this is true:

- The movie trailer for Francis Ford Coppola’s new film got pulled from theaters because “the studio had been duped by an AI bot“.

- Just one person in North Carolina was able to steal $10 million in royalties from human musicians with AI-generated songs. They got billions of streams.

- The promoters of National Novel Writing Month angrily declared that opposition to AI books is classist and ableist.

- Children are now routinely using AI to make nude photos of other youngsters.

- Nearly half of the safety team at OpenAI left their jobs — and almost nobody seems to care or notice.

- AI tech titan Nvidia lost a half trillion in market capitalization over the course of just a few days — including the largest daily decline in the history of capitalism.

- By pure coincidence, Nvidia’s CEO sold $633 million worth of stock in the weeks leading up to the current decline.

We truly live in interesting times — which is one of the three apocryphal Chinese curses.

(The other two, according to Terry Pratchett, are: “May you come to the attention of those in authority” and “May the gods give you everything you ask for”. By tradition, the last is the most dangerous of all.)

I get some credit for anticipating this. On August 4, I made the following prediction:

But it’s going to get even more interesting, and very soon. That’s because the next step in AI has arrived — the unleashing of AI agents.

And like the gods, these AI agents will give us everything we ask for.

Up until now, AI was all talk and no action. These charming bots answered your questions, and spewed out text, but were easy to ignore.

That’s now changing. AI agents will go out in the world and do things. That’s their new mission.

It’s like giving unreliable teens the keys to the family car. Up until now we’ve just had to deal with these resident deadbeats talking back, but now they are going to smash up everything in their path.

But AI agents will be even worse than the most foolhardy teen. That’s because there will be millions of these unruly bots on our digital highways.

September 8, 2024

Ancient sources

In writing history from the early modern period onward, it’s a common problem to have too many sources for a given event so that it’s the job of the historian to (carefully, one hopes) select the ones that hew closer to the objective truth. In ancient history, on the other hand, we have so few sources to rely upon that it’s a luxury to have multiple accounts of a given event from which to choose:

Unrolled papyrus scroll recovered from the Villa of the Papyri.

Picture published in a pamphlet called “Herculaneum and the Villa of the Papyri” by Amedeo Maiuri in 1974. (Wikimedia Commons)

We used to play this game in graduate school: find one, lose one. Find one referred to finding a lost ancient text, something that we know existed at one time because other ancient sources talk about it, but which has been lost to the ages. What if someone was digging somewhere in Egypt and found an ancient Greco-Roman trash dump with a complete copy of a precious text – which one would we wish into survival? Lose one referred to some ancient text we have, but we would give up in some Faustian bargain to resurrect the former text from the dead. Of course there is a bit of the butterfly effect; that’s what made it fun. As budding classicists, we grew up in an academic world where we didn’t have A, but did have B. How different would classical scholarship be if that switched? If we had had A all along, but never had B? For me, the text I always chose to find was a little-known pamphlet circulated in the late fourth century by a deposed Spartan king named Pausanias. It’s one of the few texts about Sparta written by a Spartan while Sparta was still hegemonic. I always lost the Gospel of Matthew. It’s basically a copy of Mark, right down to the grammar and syntax. Do we really need two?

What would you choose? Consider that Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey are only two of the poems that make up the eight-part Epic Cycle. Or that Aristotle wrote a lost treatise on comedy, not to mention his own Socratic dialogues that Cicero described as a “river of gold”. Or that only eight of Aeschylus’s estimated 70 plays survive. Even the Hebrew Old Testament refers to 20 ancient texts that no longer exist. There are literally lost texts that, if we had them, would in all likelihood have made it into the biblical canon.

The problem is more complex than the fact that many texts were lost to the annals of history. Most people just see the most recent translation of the Iliad or works of Cicero on the shelf at a bookstore, and assume that these texts have been handed down in a fairly predictable way generation after generation: scribes faithfully made copies from ancient Greece through the Middle Ages and eventually, with the advent of the printing press, reliable versions of these texts were made available in the vernacular of the time and place to everyone who wanted them. Onward and upward goes the intellectual arc of history! That’s what I thought, too.

But the fact is, many of even the most famous works we have from antiquity have a long and complicated history. Almost no text is decoded easily; the process of bringing readable translations of ancient texts into the hands of modern readers requires the cooperation of scholars across numerous disciplines. This means hours of hard work by those who find the texts, those who preserve the texts, and those who translate them, to name a few. Even with this commitment, many texts were lost – the usual estimate is 99 percent – so we have no copies of most of the works from antiquity.1 Despite this sobering statistic, every once in a while, something new is discovered. That promise, that some prominent text from the ancient world might be just under the next sand dune, is what has preserved scholars’ passion to keep searching in the hope of finding new sources that solve mysteries of the past.

And scholars’ suffering paid off! Consider the Villa of the Papyri, where in the eighteenth century hundreds, if not thousands, of scrolls were discovered carbonized in the wreckage of the Mount Vesuvius eruption (79 AD), in a town called Herculaneum near Pompeii. For over a century, scholars have hoped that future science might help them read these scrolls. Just in the last few months – through advances in computer imaging and digital unwrapping – we have read the first lines. This was due, in large part, to the hard work of Dr. Brent Seales, the support of the Vesuvius Challenge, and scholars who answered the call. We are now poised to read thousands of new ancient texts over the coming years.

[…]

Now let’s look at a text with a very different history, the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia. The Hellenica Oxyrhynchia is the name given to a group of papyrus fragments found in 1906 at the ancient city of Oxyrhynchus, modern Al-Bahnasa, Egypt (about a third of the way down the Nile from Cairo to the Aswan Dam). These fragments were found in an ancient trash heap. They cover Greek political and military history from the closing years of the Peloponnesian War into the middle of the fourth century BC. In his Hellenica, Xenophon covers the exact same time frame and many of the same events.2 Both accounts pick up where Thucydides, the leading historian of the Peloponnesian War (fought between Athens and Sparta in the fifth century BC), leaves off.

While no author has been identified for the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia, the grammar and style date the text to the era of the events it describes. This is a recovered text, meaning it was completely lost to history and only discovered in the early twentieth century. Here, the word discovered is appropriately used, as this was not a text that was renowned in ancient times. No ancient historians reference it, and it did not seem to have a lasting impact in its day. What is dismissible in the past is forgotten in the present. The text is written in Attic Greek. This implies that whoever wrote the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia must have been an elite familiar enough with the popular Attic style to replicate it, and likely intended for the history to equal those of Thucydides and Xenophon. There were other styles available to use at the time but Attic Greek was the style of both the aforementioned historians, as well as the writing style of the elite originating in Athens. Any history not written in Attic would have been seen as inferior. Given that the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia was lost for thousands of years, it would seem our author failed in his endeavor to mirror the great historians of classical Greece.

The Hellenica Oxyrhynchia serves as a reminder that the modern discovery of ancient texts continues. Many times, these are additional copies of texts we already have. This is not to say these copies are not important. Such was the case of the aforementioned Codex Siniaticus, discovered by biblical scholar Konstantin von Tischendorf in a trash basket, waiting to be burned, in a monastery near Mount Sinai in Egypt in 1844. Upon closer examination, Tischendorf discovered this “trash” was in fact a nearly complete copy of the Christian Bible, containing the earliest complete New Testament we have. One major discrepancy is that the famous story of Jesus and the woman taken in adultery – from which the oft-quoted passage “let he who is without sin cast the first stone” originates – is not found in the Codex Sinaiticus.

Yet, sometimes something truly new to us, that no one has seen for thousands of years, is unearthed. In the case of the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia, no one seemingly had looked at this text for at least 1,500 years, maybe more. This demonstrates that there is always the possibility that buried in some ancient scrap heap in the desert might be a completely new text that, once published for wider scholarship, greatly increases our knowledge of the ancients.

How does this specific text increase our knowledge? Bear in mind that before this period of Greek history, we have just one historian per era. Herodotus is the only source we have for the Greco-Persian Wars (480–479), and the aforementioned Thucydides picks up from there and quickly covers the political climate before beginning his history proper with the advent of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC. But Thucydides’s history is unfinished – one ancient biography claims he was murdered on his way back to Athens around 404 BC. Many doubt this, citing evidence that he lived into the early fourth century BC. Either way, his narrative ends abruptly. Xenophon picks it up from there, and later we get a more brief history of this period from Diodorus, who wrote much later, between 60 and 30 BC. While describing the same time frame and many of the same events, these two sources vary widely in their descriptions of certain events. In some cases, they make mutually exclusive claims. One historian must have got it wrong.

For centuries, Xenophon’s account was the preferred text. That is not to say Diodorus’s history was dismissed, but when the two accounts were in conflict, Xenophon’s testimony got the nod. This was partially because Xenophon actually lived during the times he wrote about, whereas Diodorus lived 200 years after these events in Greek history. Consider if there were two conflicting accounts of the Battle of Gettysburg from two different historians: one actually lived during and participated in the war, while the other was a twenty-first century scholar living 150 years after the events he describes. They disagree on key elements of the battle. Who do you believe? This was precisely the case with Xenophon and Diodorus. Yet, once the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia was published, it corroborated Diodorus’s history far more than that of Xenophon, forcing historians to reconsider their bias toward the older of the two accounts.

1. You can find a list of texts we know that we have lost at the Wikipedia page “Lost literary work“.

2. “Oxyrhynchus Historian”, in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. MC Howatson (Oxford University Press, 2011).

August 29, 2024

Pavel Durov’s arrest isn’t for a clear crime, it’s for allowing everyone access to encrypted communications services

J.D. Tuccille explains the real reason the French government arrested Pavel Durov, the CEO of Telegram:

It’s appropriate that, days after the French government arrested Pavel Durov, CEO of the encrypted messaging app Telegram, for failing to monitor and restrict communications as demanded by officials in Paris, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg confirmed that his company, which owns Facebook, was subjected to censorship pressures by U.S. officials. Durov’s arrest, then, stands as less of a one-off than as part of a concerted effort by governments, including those of nominally free countries, to control speech.

“Telegram chief executive Pavel Durov is expected to appear in court Sunday after being arrested by French police at an airport near Paris for alleged offences related to his popular messaging app,” reported France24.

A separate story noted claims by Paris prosecutors that he was detained for “running an online platform that allows illicit transactions, child pornography, drug trafficking and fraud, as well as the refusal to communicate information to authorities, money laundering and providing cryptographic services to criminals”.

Freedom for Everybody or for Nobody

Durov’s alleged crime is offering encrypted communications services to everybody, including those who engage in illegality or just anger the powers that be. But secure communications are a feature, not a bug, for most people who live in a world in which “global freedom declined for the 18th consecutive year in 2023”, according to Freedom House. Fighting authoritarian regimes requires means of exchanging information that are resistant to penetration by various repressive police agencies.

“Telegram, and other encrypted messaging services, are crucial for those intending to organise protests in countries where there is a severe crackdown on free speech. Myanmar, Belarus and Hong Kong have all seen people relying on the services,” Index on Censorship noted in 2021.

And if bad people occasionally use encrypted apps such as Telegram, they use phones and postal services, too. The qualities that make communications systems useful to those battling authoritarianism are also helpful to those with less benign intentions. There’s no way to offer security to one group without offering it to everybody.

As I commented on a post on MeWe the other day, “Somehow the governments of the west are engaged in a competition to see who can be the most repressive. Canada and New Zealand had the early lead, but Australia, Britain, Germany, and France have all recently moved ahead in the standings. I’m not sure what the prizes might be, but I strongly suspect “a bloody revolution” is one of them (if not all of them).”