In City Journal, Nicholas Wade discusses the technical side of the ongoing attempts to read one of the Herculaneum scrolls:

A computer scientist has labored for 21 years to read carbonized ancient scrolls that are too brittle to open. His efforts stand at last on the brink of unlocking a vast new vista into the world of ancient Greece and Rome.

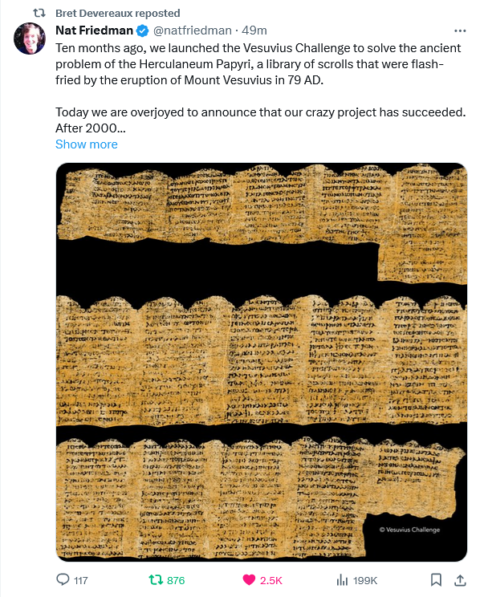

Brent Seales, of the University of Kentucky, has developed methods for scanning scrolls with computer tomography, unwrapping them virtually with computer software, and visualizing the ink with artificial intelligence. Building on his methods, contestants recently vied for a $700,000 prize to generate readable sections of a scroll from Herculaneum, the Roman town buried in hot volcanic mud from the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D.

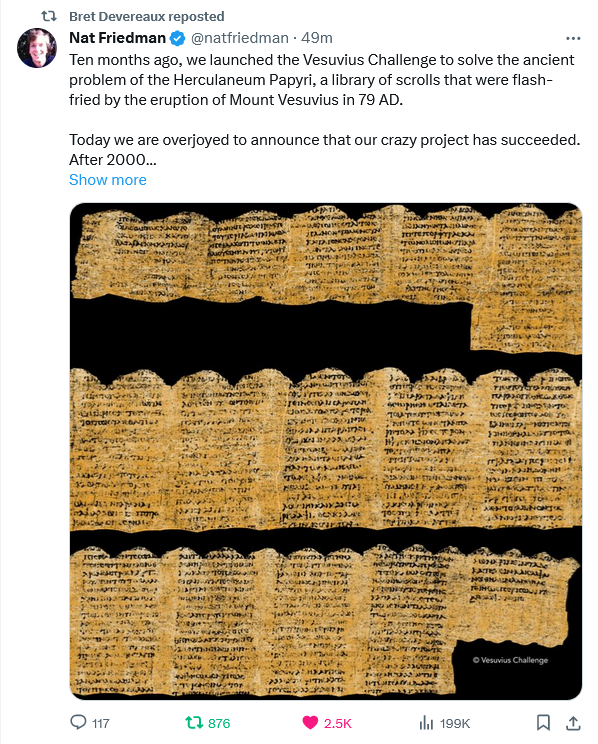

The last 15 columns — about 5 percent—of the unwrapped scroll can now be read and are being translated by a team of classical scholars. Their work is hard, as many words are missing and many letters are too faint to be read. “I have a translation but I’m not happy with it,” says a member of the team, Richard Janko of the University of Michigan. The scholars recently spent a session debating whether a letter in the ancient Greek manuscript was an omicron or a pi.

[…]

Seales has had to overcome daunting obstacles to reach this point, not all of them technical. The Italian authorities declined to make any of the scrolls available, especially to a lone computer scientist with no standing in the field. Seales realized that he had to build a coalition of papyrologists and conservationists to acquire the necessary standing to gain access to the scrolls. He was eventually able to x-ray a Herculaneum scroll in Paris, one of six that had been given to Napoleon. To find an x-ray source powerful enough to image the scroll without heating it, he had to buy time on the Diamond particle accelerator at Harwell, England.

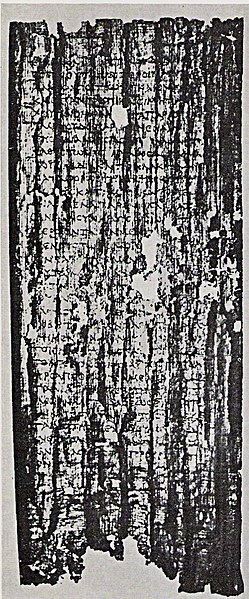

In 2009, his x-rays showed for the first time the internal structure of a scroll, a daunting topography of a once-flat surface tugged and twisted in every direction. Then came the task of writing software that would trace the crumpled spiral of the scroll, follow its warped path around the central axis, assign each segment to its right position on the papyrus strip, and virtually flatten the entire surface. But this prodigious labor only brought to light a more formidable problem: no letters were visible on the x-rayed surface.

Seales and his colleagues achieved their first notable success in 2016, not with Napoleon’s Herculaneum scroll but with a small, charred fragment from a synagogue at the En-Gedi excavation site on the shore of the Dead Sea. Virtually unwrapped by the Seales software, the En-Gedi scroll turned out to contain the first two chapters of Leviticus. The text was identical to that of the Masoretic text, the authoritative version of the Hebrew Bible — and, at nearly 2,000 years old, its earliest instance.

The ink used by the Hebrew scribes was presumably laden with metal, and the letters stood out clearly against their parchment background. But the Herculaneum scroll was proving far harder to read. Its ink is carbon-based and almost impossible for x-rays to distinguish from the carbonized papyrus on which it is written. The Seales team developed machine-learning programs — a type of artificial intelligence — that scanned the unrolled surface looking for patterns that might relate to letters. It was here that Seales found use for the fragments from scrolls that earlier scholars had destroyed in trying to open them. The machine-learning programs were trained to compare a fragment holding written text with an x-ray scan of the same fragment, so that from the statistical properties of the papyrus fibers they could estimate the probability of the presence of ink.