It has become popular of late to associate strategy with a “theory of victory”. Many policy pieces and journal articles define this as a narrative explanation of why a particular strategy will work — something every strategy must contain, if only implicitly. Others go so far as to insist that a strategy is nothing more than a theory of victory. […]

Strategy itself is a slippery term, used in slightly different ways in different contexts. In everyday usage, it is simply a plan to accomplish some task, whereas formal military definitions tend to specify the particular end. The US joint doctrinal definition, for instance, is: “A prudent idea or set of ideas for employing the instruments of national power in a synchronized and integrated fashion to achieve theater, national, and/or multinational objectives”. If strategy is not quite a theory for victory, the connection between them is apparent.

There is a subtle problem with this definition, however. Victories are rarely won in precisely the way the victors anticipate. Few commanders can call their own shots, as Napoleon did in Italy or William Slim in Burma. Wars are complex and messy things, and good strategy requires constant adaptation to circumstance — a system of expedients, as Moltke put it. Even with the benefit of hindsight, the cause of a war’s outcome is not always perfectly clear, as the ongoing debate over strategic bombing bears witness.

Indeed, the very idea that strategy represents a plan is very recent. From the first adoption of the word into modern languages,1 strategy was defined more as an art: of “commanding and of skilfully employing the means [the commander] has available”, of “campaigning”, of “effectively directing masses in the theater of war”. The emphasis was decidedly on execution, not planning. As recently as 2001, the US Army’s FM 3-0 Operations defined strategy as: “the art and science of developing and employing armed forces and other instruments of national power in a synchronized fashion to secure national or multinational objectives”. Something one does, not something one thinks.

This is best understood by analogy to tactics, a realm less given to formalism and abstraction. What makes a good tactician? Devising a good plan is certainly part of it, but most tactical concepts are not especially unique — there are only so many tools in the tactical toolkit. The real challenge lies in execution: providing for comms and logistics, ensuring subordinates understand the plan, going through rehearsals, making sure that everyone is doing their job correctly, then putting oneself at the point where things are likely to go wrong and dealing with the unexpected.

Ben Duval, “Is Strategy Just a Theory of Victory? Notes on an Annoying Buzzword”, The Bazaar of War, 2024-12-01.

1. This was before Clausewitz’s inadvertent redefinition of strategy, when the term still referred to what we now call “operational art”.

March 15, 2025

QotD: Strategy

March 13, 2025

Leadership of HMCS Harry DeWolf take a TOUR of HMCS Haida National Historic Site, Parks Canada

Royal Canadian Navy / Marine Royale Canadienne

Published 10 Nov 2024Canada’s “most fightingest ship” served in our Navy for 20 years between 1943 and 1963. The last Tribal Class Destroyer in the world, it and its company persevered through the Second World War, Korean War and Cold War.

The ceremonial flagship of our Navy, HMCS Haida was saved from the scrapyards and now rests in Hamilton as a museum ship, a Parks Canada National Historic Site.

One of HMCS Haida‘s Captains was the Naval hero Harry DeWolf — the namesake of the Harry DeWolf Class of ships. The grandson of a Veteran who served on the ship recently took the leadership of HMCS Harry DeWolf for a tour after arriving alongside, showing the stark differences between the newest vessels of our fleet and this vintage destroyer showing the many differences between life in the Navy then and now.

#CanadaRemembers #HelpLeadFight

March 12, 2025

The Korean War 038 – The US President is Angry! – March 11, 1951

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 11 Mar 2025Operation Ripper kicks off this week, and gains plenty of ground … but the enemy is almost nowhere to be found. Douglas MacArthur gives what becomes known as his “die for a tie” speech, which could have a serious negative effect on UN troop morale. But the Chinese are building up their forces for an eventual counterstrike, and the North Koreans even have a new Chief of Staff.

Chapters

00:00 Intro

00:50 Recap

01:15 Plans for Operation Ripper

04:45 Die for a Tie

06:34 MacArthur Won’t Toe the Line

08:17 The KPA Build-Up

10:38 Nam Il

12:31 The Chinese Build-Up

14:01 Ripper Begins

15:33 Summary

15:45 Conclusion

(more…)

Colt Sidehammer “Root” Dragoon Prototype

Forgotten Weapons

Published 17 Nov 2016During the development of the 1860 Army revolver, Colt did consider mechanical options other than simply scaling up the 1851 Navy pattern. One of these, as evidenced by this Colt prototype, was an enlarged version of the 1855 Pocket, aka “Root”, revolver. That 1855 design used a solid frame and had been the basis for Colt’s revolving rifles and shotguns, and so it would be natural to consider it for use in a .44-caliber Army revolver. How extensive the experimentation was is not known, and I believe this is the only known surviving prototype of a Dragoon-size 1855 pistol. It survives in excellent shape, and is a really neat glimpse at what might have been …

March 10, 2025

Chinese Civil War Part 1 – W2W 11 – Q1 1947

TimeGhost History

Published 9 Mar 2025After WWII, China is plunged into chaos as Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Mao Zedong’s Communists reignite a decades-old conflict. This episode traces the roots of the Chinese Civil War — from the guerrilla strategies honed in Yan’an to the shifting power dynamics after Japanese occupation. Discover how ideological fervor, battle-hardened tactics, and the struggle for legitimacy set China on a path that would redefine its future.

(more…)

March 9, 2025

Europe’s leaders start talking about rearmament

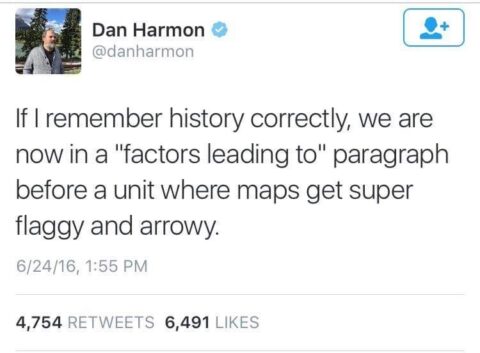

Yet another side-effect of the Trumpening has been a shift in attitude among European leaders on the issue of self-defence and military spending. eugyppius points out that the flashy new media campaign to drum up support for the new position has “borrowed” its design from an unfortunate donor:

For three years we have had war in Ukraine, masterminded on the NATO side by senile warmonger-in-chief Joe Biden. This war included bizarre moments, like direct attacks on German energy infrastructure, and also escalatory brinksmanship, as when Biden authorised long-range missile strikes within Russian territory, and the Russians responded with a not-so-subtle threat of nuclear retaliation. Throughout all of this madness, the Europeans slept, sparing hardly a single thought for their defence. Now that Donald Trump hopes to end the war in Ukraine, however, Continental political leaders are losing their minds. War: not scary at all. Peace: an existential threat.

The first way our leaders hope to dispel the disturbing spectre of peace, is via Ursula von der Leyen’s “ReArm Europe” initiative, which will permit member states to take on billions in debt to fund their rearmament. In this way, the clueless histrionic Brussels juggernaut hopes (in the words of Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk) to “join and win the arms race” with Russia, even if (in the words of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung – h/t the incomparable Roger Köppel) we must “avoid for the moment a confrontation with the new Washington”. Becoming a global superpower with a view towards confronting the hated Americans is all about spending and time, you don’t need strategy or a plan or anything like that.

Those of you wondering whether it might be a better idea to rearm first and then set about alienating our powerful geopolitical partners simply lack the Eurotardian vision. These are such serious people, that in the space of a few days they spun up this remarkable logo for their spending programme …

… which obviously portrays the EU member states smearing yellow warpaint on themselves and in no way evokes the most notorious obscene internet image of all time. Nations just do stuff, but the Eurotards cannot even take a shit without bizarre hamfisted branding campaigns.

As I said, these are deeply serious people, and they also speak very seriously, in declarative sentences that don’t mean anything. In a publicity statement, von der Leyen said that these are “extraordinary times” which are a “watershed moment” for Europe and also a “watershed moment for the Ukraine”. Such extraordinary watersheds require “special measures,” such as “peace through strength” and “defence” through “investment”. Top EU diplomat and leading Estonian crazy person Kaja Kallas for her part noted that “We have initiative on the table” and that she’s “looking forward to seeing Europe show unity and resolve”. Perhaps there will also be money in the ReArm Europe programme to outfit Brussels with an arsenal of thesauruses so we do not have to hear the same words all the time.

At Roots & Wings, Frank Furedi says that “Europe Has Just Become A More Dangerous Place” thanks to the shift to “military Keynsianism” where future economic growth is mortgaged to current military spending:

Of course, it is still early days, and wise counsel may well prevail over Europe’s jingoistic shift towards a war economy. The justification for opting for military Keynesianism is the supposed threat posed by Russia to European security and the necessity for defending the integrity of Ukraine. However, it is evident to all that even if all the billions earmarked for the defense of Europe are invested wisely it will have little bearing on developments on the battlefields of Ukraine. Converting Germany’s ailing automobile industry to produce military hardware will take years as will the process of transforming Western Europe’s existing security resources into a credible military force.

Just remember that Germany’s railway infrastructure is currently in too poor a state to transfer tanks and other military hardware across the country. Years of obsessing with Net Zero Green ideology have taken their toll on Germany’s once formidable economy.

It is an open secret that Europe has seriously neglected its defence infrastructure. It is also the case that initiatives led by the EU and other European institutions are implemented at a painfully slow pace. The failure of the EU to offer an effective Europe wide response to the Covid pandemic crisis exposed the sorry state of this institutions capacity to deal with an emergency. The EU is good at regulating but not at getting things done. The EU’s regulatory institutions are more interested in regulating than in implementing a complex plan designed to rearm the continent.

Nor is the problem of transforming European defense into a credible force simply an matter to do with military hardware. European armies – Britain and France included – are poorly prepared for a war. The nations of the EU have become estranged from the kind of patriotic values necessary to support a real military engagement with Russia. Keir Starmer’s “coalition of the willing” raises the question of “willing to do what?”. At a time when neither France nor Britain can secure their borders to prevent mass illegal migration their willingness to be willing will be truly tested.

Macron and his colleagues may well be good at acting the role of would-be Napoleon Bonapartes. But these windbags are not in a position seriously affect the outcome of the war in Ukraine. As matters stand only the United States has the resources and the military-technological capacity to significantly influence the outcome of this war.

While all the tough talk emanating from the Brussels Bubble has a distinct performative dimension it is important to take seriously the dangers of unleashing an explosive dynamic that has the potential of quickly escalating and getting out of control. As we head towards a world of increased protectionism and economic conflict there is a danger that European rearmament could inadvertently lead to an arms race. History shows that such a development inevitably has unpredictable consequences.

What’s really concerning about the decision taken by the European Council is not simply its “spend, spend” strategy or its wager on the economic benefits of the arms industry. What is really worrying is that Europe’s leading military hawks lack clarity about the continent’s future direction of travel. Afflicted by the disease of geopolitical illiteracy the leaders of Europe have failed to address the issue of how they can navigate a world where the three dominant powers – America, China, Russia – have a disproportionately strong influence on geopolitical matters.

Italy’s Italian Fiasco

World War Two

Published 8 Mar 2025Today Sebastian puts Indy and Sparty in the hot seat for questions about the war in China and North Africa. Just what is the deal with the Italian Army anyway? How much fighting did the CCP do against the Japanese? And what’s the most overlooked event of the first year of war?

(more…)

Sulla: bloodthirsty psycho or saviour of the Republic?

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 23 Oct 2024Today’s question asked about Lucius Cornelius Sulla, the first man to the march his legions against the city of Rome, starting the first — but far from the last — of Rome’s civil wars. He killed a lot of people, broke a lot of laws and conventions, but as dictator also introduced a very “conservative” programme of reforms. How should we judge Sulla, as a selfish, brutal murderer, or as a reluctant rebel and well-intentioned reformer?

March 8, 2025

Murder in the Name of Democracy – War Against Humanity 002

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 7 Mar 2025The battles on the Korean peninsula started long before 1950. Today Sparty looks back at the uprising and insurgency on Jeju Island in 1948, the threat of Communist revolt, and the harsh reaction of the Korean government. This really was the war before the war.

(more…)

Joslyn M1862 and M1864 Carbines

Forgotten Weapons

Published 15 Jun 2015While US infantry forces during the Civil War had only limited access to the newest rifle technology, cavalry units adopted a wide variety of new carbines in significant numbers. Among these were a design by Benjamin Joslyn. It first appeared in 1855 designed to use paper cartridges, but by the time the US Army showed an interest Joslyn had updated the weapon to use brass rimfire ammunition. The first version purchased by the government was the 1862 pattern carbine, of which about a thousand were obtained. Many more were ordered, but it took Joslyn a couple years to really get his manufacturing facility and processes worked out. By the time he had this all straightened out, the design had been updated again to the 1864 pattern, addressing several minor problems with the earlier version. Ultimately more than 11,000 of the 1864 pattern carbines were purchased by the Union, chambered for the same .56-.52 cartridge as the Spencer carbines also in service.

March 7, 2025

Soviet Invasion of Finland: Winter War 1939-40

Real Time History

Published 18 Oct 2024November 1939. Germany and the Soviet Union have conquered Poland, and Germany is at war with France and Britain. Moscow is free to do as it pleases in Eastern Europe and sets its sights on Finland – but the Winter War will be a nasty surprise for Stalin.

Corrections:

02:19 The dot marking Leningrad is about 80km too far east, it’s of course directly at the far eastern end of the Gulf of Finland.

(more…)

March 6, 2025

The Iron Curtain Descends – W2W 10 – News of 1946

TimeGhost History

Published 5 Mar 20251946 sees the world teetering on the brink of a new global conflict. George Kennan’s long telegram outlines Moscow’s fanatical drive against the capitalist West, while our panel covers escalating espionage, strategic disputes over Turkey, and the emerging ideological battle between the U.S. and the USSR. Tune in as we break down the news shaping the dawn of the Cold War.

(more…)

HMCS Bonaventure – The Pride of Canada’s Fleet

Skynea History

Published 22 Oct 2024For today’s video, we’ll be looking at the last of Canada’s aircraft carriers. Not typically a navy you associate with that kind of ship, but the Canadians actually operated three during the Cold War.

The third, HMCS Bonaventure, is an interesting one. A small ship, that operated aircraft at the very edge of her capability. And routinely baffled American pilots in the process.

Yet, she was also a ship that came to an end before her time. Decommissioned and scrapped, right after an expensive (and extensive) mid-life overhaul. In what is generally seen as a bad political move, more than anything to do with her capabilities.

(more…)

March 5, 2025

The Korean War 037 – Matt the Ripper! – March 4, 1951

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 4 Mar 2025This week is really a week of planning, as Matt Ridgway unveils the plans for Operation Ripper — to follow the somewhat disappointing Operation Killer, but there are South Korean spies involved, the blockade of Wonsan, and the continuing escalation of tensions between Douglas MacArthur and Harry Truman, with people in American High Command concerned that MacArthur is bent on starting World War 3.

Chapters

00:00 Intro

00:25 Recap

00:44 Killer and Ripper

04:14 Intel and Distractions

06:57 South Korean Spies

08:06 Truman and MacArthur (Again)

(more…)