Chris Bray is deeply concerned that a free society seems unable to produce even a mild array of differing political opinions these days:

I was at a small independent bookstore today, the exact kind of place that’s supposed to curate a culture of argument and criticism. The prominently displayed books about politics and current events were Timothy Snyder’s book about the terrifying rise of American fascism under that monster Trump, Jason Stanley’s book about the terrifying rise of American fascism under that monster Trump, Anne Applebaum’s book about the terrifying rise of American fascism under that monster Trump, and a bunch of other books by prominent journalists and professors about … okay, try to guess.

On the other side of that exchange, the books by public intellectuals offering a favorable or even neutral view of Trump and the Trump era were … not there? Maybe I just missed them. So every prominent figure moving to the cultural foreground from academia and “mainstream” journalism — every brave contrarian, every freethinking intellectual warrior rising against the prevailing fascist sentiment of the age to speak in his own voice as a free person — thinks and says the same things, the same ways, with the same evidence and the same framing and the same tone and in the same state of mind. They’re so free and brave and iconoclastic that they’re essentially identical, chanting in intellectual unison.

Forget Trump for a moment and answer this question in general: If you’re living through an era in which every prominent journalist and academic and artist says exactly the same fucking thing all the time, what kind of moment are you living in? Would you call people who all chant in unison the resistance?

Any engagement with these books reveals their emptiness. Snyder, Stanley, Applebaum, whatever: pick a book, then pick a page. See if it makes sense. Here, I spent a few nauseating minutes today with brave Jason Stanley’s book How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. Here’s a paragraph from the introduction to the paperback edition:

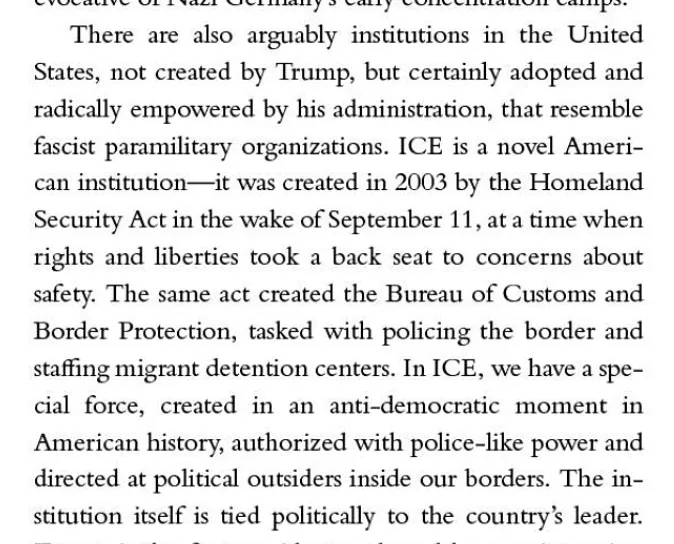

ICE is novel: It was created after 9/11, by the same law that created a bureau tasked with border protection: a “special force, created in an anti-democratic moment”.

I can’t calibrate the degree to which this person is a fool or a liar, but let’s go with both. The Border Patrol was created in 1924, and was itself the successor agency to a different organization that was created in 1904. You can read that history here. The post-9/11 organization that supposedly created this novel American institution merely reorganized a century-old American institution, making it not the least bit novel. Before ICE, we had INS. Yes, we had a border before 2003, and we policed it. This isn’t a novel concept at all, as it has operated in any form of practice.

You can go through that single amazing paragraph sentence by sentence and tear every last bit of it apart, at the lowest, simplest factual level. The argument isn’t wrong: all of it is wrong, every layer of fact and interpretation. This man is an absolutely enormous jackass. And he’s … important. An important public intellectual, you see.