… note that this is also a bit of a rebuke to the dominant strain of prepper fantasies, such as those I began this review with. Prepper fantasies are most fundamentally fantasies of agency, dreams that in the right crisis the actions you take could actually matter, and that in the wake of that crisis you could return to a Rousseauian condition of autonomous activity freed from the internal conflicts engendered by societal oppression (whether that oppression takes the form of stifling social convention or HRified bureaucratic fiat). It’s obvious how the prepper fantasies relate to the great survival stories like Robinson Crusoe, or to the pioneer dramas of the American Westward expansion. It’s a little less obvious, but just as deeply true, that they’re connected to stories of rogues, rascals, and reavers like those by Robert E. Howard or Bronze Age Pervert. All of these stories, fundamentally, are about how a man freed from external restraint and internal conflict can apply himself to better his condition.

The thing is these stories are totally ahistorical — the best that solitary survivors have ever managed was to survive, none of them have rebuilt civilization. As Jane notes in her review of BAP, the sandal-clad barbarians have generally been subjected to a “tyranny of the cousins” even more intrusive and meticulous than the gynocratic safetyism that Bronze Age Lifestyle offers an imaginative escape from. And as for the pioneers, Tanner Greer notes that:

Many imagine the great American man of the past as a prototypical rugged individual, neither tamed nor tameable, bestriding the wilderness and dealing out justice in lonesome silence. But this is a false myth. It bears little resemblance to the actual behavior of the American pioneer, nor to the kinds of behaviors and norms that an agentic culture would need to cultivate today. Instead, the primary ideal enshrined and ritualized as the mark of manhood was “publick usefuleness”, similar, if not quite identical, to the classical concept of virtus. American civilization was built not by rugged individuals but by rugged communities. Manhood was understood as the leadership of and service to these communities.

It would be too easy to end the review here, with the implication that the prepper identity is a fantasy of radical individualism and like all such fantasies, kinda dumb. But the thing is, the prepper world has by and large absorbed this critique and incorporated it into its theorizing. In contrast to the libertarian fantasies of the 1970s, second-wave prepperism (reformed prepperism?) is constantly talking about community, the importance of having friends you can trust, of cultivating deep social bonds with your neighbors, etc.

What Yu Gun reminds us is that this is still totally ahistorical, but this time in a way that indicts not only the preppers, but also a much broader swathe of our society. A man without a community is unnatural, but so is a community without leadership, hierarchy, and order. The prepper version of community is a vision of freely contracting individuals respecting each others’ autonomy while cooperating because it’s in their best interests. This is also the folk version of community that motivates much of our economic and legal regime. Scratch an American “communitarian”, and underneath it’s just another individualist.

If you hang out on prepper forums, a recurrent mantra is to “practice your preps”, that is to start living on the margin as if the apocalypse had already occurred. The purpose of this is to gain experience in the skills you’ll need after the end, and to work out the kinks in your routine now, while it’s still easy to make adjustments. Originally this meant practicing getting lost in the woods, using and maintaining your weapon of choice, eating some of your food stockpile, or whatever. In second-wave prepperism it means all that, plus a bunch of new stuff like hanging out with your neighbors, attending community barbecues, and whatever else it is that freely contracting individuals like to autonomously do while temporarily occupying the same space.

But for we third-wave preppers, it has to take on a very different meaning. Greer’s essay that I quoted above is mainly about how leadership and service in local-scale organizations served as training for leadership and service in much larger groups aimed at problems with much higher stakes. In other words, they were practicing their preps. One of the great secrets of leadership is that following and leading are actually closely related skills, and that practice at one of them transfers well to the other. This is difficult for we Americans to see, because an aversion to hierarchy is built into our national character, and consequently we operate with impoverished models of what it means to be in a position of authority or of subordination.

Long ago I read an article contrasting Western and Korean massively-multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs). Even if you know nothing about computer games, you probably know that in most of them you are the hero, the chosen one, the child of destiny. Talk about fantasies of agency! MMORPGs thus have a tricky needle to thread — somehow all the thousands and thousands of players need to simultaneously be the chosen one, the child of destiny, etc., etc. And they mostly accomplish this by just rolling with it and asking everybody to suspend disbelief. But this article claimed that Korean MMORPGs are different — when players join these games, they’re randomly assigned a role. A tiny fraction might become kings or generals or children of destiny, with the power to decide the fates of peoples and kingdoms, but most are given a role as ordinary soldiers or porters or blacksmiths, and toil away at their in-game mundane tasks, without much ability to affect anything at all.

We like to imagine that after the bombs fall and the smoke clears we will emerge as the new Yu Gun, apportioning merit and assigning tasks. And perhaps you will indeed be called upon to do that, so you should prepare yourself to step up and do it. That preparation will involve some practice commanding others and some practice obeying others’ commands, because the two are inextricably bound together. But in life as in Korean video games, there’s isn’t very much room at the top. Far more likely, when the stage of history is set, we will be cast in a supporting role, like the Korean gamer assigned to role-play as a peasant or like Yu’s followers standing in orderly ranks. Let us not turn our noses up at this vocation, the poorly-behaved seldom make history.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900 by David A. Graff”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-06-05.

April 12, 2024

QotD: Prepper fantasy versus prepper reality

April 7, 2024

Instructions for American Servicemen in Britain (1942)

Henry Getley on the US War Department publication Instructions for American Servicemen in Britain produced for incoming GIs on arrival in Britain from early in 1942:

[W]ith their troops pouring into this country from 1942 onwards to prepare for D-Day, officials at the US War Department did their best to make the culture clash as trouble-free as possible. One of their main efforts was issuing GIs with a seven-page foolscap leaflet called Instructions for American Servicemen in Britain.

It’s available in reprint as a booklet and makes fascinating reading, not least for its straightforward, jargon-free writing style and its overriding message – telling the Yanks to use “plain common horse sense” in their dealings with the British.

In parts, it now seems clumsy and condescending. But its purpose was praiseworthy – to try to get American troops to damp down the impression that they were overpaid, oversexed and over here. Many GIs qualified in all three aspects, of course, but you couldn’t blame the top brass for trying.

The leaflet paints a sympathetic (some would say patronising) picture for the incoming Americans of a Britain – “a small crowded island of forty-five million people” – that had been at war for three years, having initially stood alone against Hitler and braved the Blitz. Hence this “cradle of democracy” was now a “shop-worn and grimy” land of rationing, the blackout, shortages and austerity. But beneath the shabbiness, there was steel.

The British are tough. Don’t be misled by the British tendency to be soft-spoken and polite. If need be, they can be plenty tough. The English language didn’t spread across the oceans and over the mountains and jungles and swamps of the world because these people were panty-waists.

There were helpful hints about cricket, football, darts, pounds, shillings and pence, warm beer and badly-made coffee. And because we are two nations divided by a common language, the Yanks were urged to listen to the BBC.

In England the “upper crust” speak pretty much alike. You will hear the newscaster for the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation). He is a good example, because he has been trained to talk with the “cultured” accent. He will drop the letter “r” (as people do in some sections of our own country) and will say “hyah” instead of “here”. He will use the broad “a”, pronouncing all the a’s in “banana” like the “a” in father.

However funny you may think this is, you will be able to understand people who talk this way and they will be able to understand you. And you will soon get over thinking it’s funny. You will have more difficulty with some of the local accents. It may comfort you to know that a farmer or villager from Cornwall very often can’t understand a farmer or villager in Yorkshire or Lancashire.

The GIs were warned against bravado and bragging, being told that the British were reserved but not unfriendly. “They will welcome you as friends and allies, but remember that crossing the ocean doesn’t automatically make you a hero. There are housewives in aprons and youngsters in knee pants in Britain who have lived through more high explosives in air raids than many soldiers saw in first-class barrages during the last war.”

April 5, 2024

April 2, 2024

Rob Henderson reviews Noise by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony & Cass R. Sunstein

Rob Henderson reviews the last published work of Nobel prize winner Daniel Kahneman and his co-authors Olivier Sibony and Cass R. Sunstein:

Are crowds smart or dumb? You may have heard the terms “wisdom of the crowds” and the “madness of crowds”. The former idea is that the collective opinion of a group of people is often more accurate than any individual person, and that gathering input from many individuals averages out the errors of each person and produces a more accurate answer. In contrast, the “madness of crowds” captures the idea that, relative to a single individual, large numbers of people are more likely to indulge their passions and get carried away by impulsive or destructive behaviors. So, which concept more accurately reflects reality?

Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgement by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass R. Sunstein provides the answer. The authors share research indicating that “independence is a prerequisite for the wisdom of crowds”. That is, if you want to use crowdsourcing to produce accurate information, you have to ensure that people make their judgments in private. If people provide their answers in a public setting where they can see everyone else’s answers, then the crowd can transform wisdom into madness.

Relatedly, Wharton organizational psychologist Adam Grant has stated that “you get more and better ideas if people are working alone in separate rooms than if they are brainstorming in a group. When people generate ideas together, many of the best ones never get shared. Some members dominate the conversation, others hold back to avoid looking foolish, and the whole group tends to conform to the majority’s taste.” People converge on ideas they believe are held by the majority, when often they are simply acquiescing to the most assertive and strident members of the group. Grant suggests that the best way to sidestep this problem is to have people think up ideas on their own before the group evaluates them.

In Noise, Kahneman and his colleagues report findings indicating that, in tasks involving estimation, such as the number of crimes in a city or geographic distances, crowds are wise as long as they registered their views independently. But if people learn what others estimated, then crowds do worse than individuals. The book states that, “while multiple independent opinions, properly aggregated, can be strikingly accurate, even a little social influence can produce a kind of herding that undermines the wisdom of the crowds”.

There are many reasons why Kahneman’s 2011 book Thinking, Fast and Slow became a groundbreaking hit, while Noise did not reach quite the same heights (Kahneman and his statistically savvy co-authors might cite regression toward the mean). One reason for the difference may be the years in which the books were published. In 2011, the educated class generally favored meritocratic and objective measures for judgment and decision-making. They found the message that we should challenge the role of bias in our everyday judgments appealing, and believed that we should rid ourselves of habits that lead us to judge other people or situations unfairly. Today, however, much of intellectual culture has changed. Now that luxury beliefs are ascendant, relying on objective measures is no longer fashionable.

Publishing and the AI menace

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte fiddles around a bit with some of the current AI large language models and tries to decide how much he and other publishers should be worried about it:

The literary world, and authors in particular, have been freaking out about artificial intelligence since ChatGPT burst on the scene sixteen months ago. Hands have been wrung and class-action lawsuits filed, none of them off to auspicious starts.

The principal concern, according to the Authors Guild, is that AI technologies have been “built using vast amounts of copyrighted works without the permission of or compensation to authors and creators,” and that they have the potential to “cheaply and easily produce works that compete with — and displace — human-authored books, journalism, and other works”.

Some of my own work was among the tens of thousands of volumes in the Books3 data set used without permission to train the large language models that generate artificial intelligence. I didn’t know whether to be flattered or disturbed. In fact, I’ve not been able to make up my mind about anything AI. I’ve been playing around with ChatGPT, DALL-E, and other models to see how they might be useful to our business. I’ve found them interesting, impressive in some respects, underwhelming in others.

Unable to generate a newsletter out of my indecision, I called up my friend Thad McIlroy — author, publishing consultant, and all-around smart guy — to get his perspective. Thad has been tightly focused on artificial intelligence for the last couple of years. In fact, he’s probably the world’s leading authority on AI as it pertains to book publishing. As expected, he had a lot of interesting things to say. Here are some of the highlights, loosely categorized.

THE TOOLS

I described to Thad my efforts to use AI to edit copy, proofread, typeset, design covers, do research, write promotional copy, marketing briefs, and grant applications, etc. Some of it has been a waste of time. Here’s what I got when I asked DALL-E for a cartoon on the future of book publishing:

In fairness, I didn’t give the machine enough prompts to produce anything decent. Like everything else, you get out of AI what you put into it. Prompts are crucial.

For the most part, I’ve found the tools to be useful, whether for coughing up information or generating ideas or suggesting language, although everything I tried required a good deal of human intervention to bring it up to scratch.

I had hoped, at minimum, that AI would be able to proofread copy. Proofreading is a fairly technical activity, based on rules of grammar, punctuation, spelling, etc. AI is supposed to be good at following rules. Yet it is far from competent as a proofreader. It misses a lot. The more nuanced the copy, the more it struggles.

March 28, 2024

QotD: Honest scholarship … and whatever passes for scholarship these days

Although not one in ten thousand academics and other intellectuals would express dissent from what Bob says above [Bob Higgs’ post on Facebook], quite a few express their disregard for what he says through their actions. As Bob notes, an excellent example of this academic utter shoddiness or execrable dishonesty (you pick) is Duke University “historian” Nancy MacLean and her well-documented penchant for presenting fabrications as facts. Another example is Cornell University “historian” Ed Baptist.

Equally distressing as these (and an increasing number of other) examples of scholarly utter shoddiness or execrable dishonesty is the complete incredulity of many people in accepting the “findings” of such “scholars”.

A perverted form of amusement can be had by imagining what sort of “scholarly” output you might offer to the world were you to operate according to the standards used by “scholars” such as Nancy MacLean. Free to present fiction as fact, you might, say, claim that because Dr. MacLean studied at the University of Wisconsin, and because Wisconsin was once home to the serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer – and because in her book Democracy in Chains she did not explicitly denounce serial killing – that Dr. MacLean’s work is a surreptitious attempt to justify serial killing.

Of course, any such conclusion would be both preposterous and inexcusably unethical. Anyone who (unlike me here) seriously offered such a wacky, detached-from-all-reality, ideologically motivated thesis to the public should lose not only any claim to scholarly respect, but any claim to respect of any sort. And yet the bases for the conclusions reached by “scholars” such as Dr. MacLean are no more realistic than are those in my previous, satirical paragraph.

Don Boudreaux, “The Wisdom of Bob Higgs”, Café Hayek, 2019-08-29.

March 26, 2024

What Makes a Good Book

Lost Art Press

Published Nov 26, 2023✅ Read and subscribe to the Lost Art Press Blog: https://blog.lostartpress.com/

🏪 Visit Our Store: https://lostartpress.com

March 25, 2024

Vernor Vinge, RIP

Glenn Reynolds remember science fiction author Vernor Vinge, who died last week aged 79, reportedly from complications of Parkinson’s Disease:

Vernor Vinge has died, but even in his absence, the rest of us are living in his world. In particular, we’re living in a world that looks increasingly like the 2025 of his 2007 novel Rainbows End. For better or for worse.

[…]

Vinge is best known for coining the now-commonplace term “the singularity” to describe the epochal technological change that we’re in the middle of now. The thing about a singularity is that it’s not just a change in degree, but a change in kind. As he explained it, if you traveled back in time to explain modern technology to, say, Mark Twain – a technophile of the late 19th Century – he would have been able to basically understand it. He might have doubted some of what you told him, and he might have had trouble grasping the significance of some of it, but basically, he would have understood the outlines.

But a post-singularity world would be as incomprehensible to us as our modern world is to a flatworm. When you have artificial intelligence (and/or augmented human intelligence, which at some point may merge) of sufficient power, it’s not just smarter than contemporary humans. It’s smart to a degree, and in ways, that contemporary humans simply can’t get their minds around.

I said that we’re living in Vinge’s world even without him, and Rainbows End is the illustration. Rainbows End is set in 2025, a time when technology is developing increasingly fast, and the first glimmers of artificial intelligence are beginning to appear – some not so obviously.

Well, that’s where we are. The book opens with the spread of a new epidemic being first noticed not by officials but by hobbyists who aggregate and analyze publicly available data. We, of course, have just come off a pandemic in which hobbyists and amateurs have in many respects outperformed public health officialdom (which sadly turns out to have been a genuinely low bar to clear). Likewise, today we see people using networks of iPhones (with their built in accelerometers) to predict and observe earthquakes.

But the most troubling passage in Rainbows End is this one:

Every year, the civilized world grew and the reach of lawlessness and poverty shrank. Many people thought that the world was becoming a safer place … Nowadays Grand Terror technology was so cheap that cults and criminal gangs could acquire it. … In all innocence, the marvelous creativity of humankind continued to generate unintended consequences. There were a dozen research trends that could ultimately put world-killer weapons in the hands of anyone having a bad hair day.

Modern gene-editing techniques make it increasingly easy to create deadly pathogens, and that’s just one of the places where distributed technology is moving us toward this prediction.

But the big item in the book is the appearance of artificial intelligence, and how that appearance is not as obvious or clear as you might have thought it would be in 2005. That’s kind of where we are now. Large Language Models can certainly seem intelligent, and are increasingly good enough to pass a Turing Test with naïve readers, though those who have read a lot of Chat GPT’s output learn to spot it pretty well. (Expect that to change soon, though).

One major change in sexual behaviour since the mid-20th century

David Friedman usually blogs about economics, medieval cooking, or politics. His latest post carefully avoids (almost) all of that:

I didn’t have a convenient graphic to use for this post … but I know not to Google something like this.

My picture of sexual behavior now and in the past is based on a variety of readily observable sources — free online porn for the present, writing, both pornography and non-pornographic but explicit, for the past. On that imperfect and perhaps misleading evidence the pattern of when oral sex was or was not common in our society in recent centuries is the opposite of what one would, on straightforward economic grounds, expect.

Casanova’s memoirs provide a fascinating picture of eighteenth century Europe, including its sexual behavior. He mentions incest, male homosexuality, lesbianism, which he regards as normal for unmarried girls:

Marton told Nanette that I could not possibly be ignorant of what takes place between young girls sleeping together.

“There is no doubt,” I said, “that everybody knows those trifles …

I do not believe he ever mentions either fellatio or cunnilingus. Neither does Fanny Hill, published in London in 1748, when Casanova was twenty-three.

Frank Harris, writing in the early 20th century, is familiar with cunnilingus, uses it as a routine part of his seduction tactics, but treats it as something sufficiently exotic so that he had to be talked into trying it by a woman unwilling to risk pregnancy. I do not think he ever mentions fellatio.

Modern online porn in contrast treats both fellatio and cunnilingus as normal parts of foreplay, what routinely comes between erotic kissing and vaginal intercourse.

One online article on the history of fellatio that I found dated the change in attitudes to after the 1976 Hite Report, which found a strongly negative attitude among women to performing it. In contrast:

Today, the act is something more like bread before dinner: noteworthy only if it’s absent. (Fifty Shades of Grey and How One Sex Act Went Mainstream)

And from another, present behavior:

Oral sex precedes and often replaces sexual intercourse because it’s perceived to be noncommittal, quick and safe. For some kids it’s a cool thing to do; for others it’s a cheap thrill. Raised in a culture in which speed is valued, kids, not surprisingly, seek instant gratification through oral sex (the girl by instantly pleasing the boy, the boy by sitting back and enjoying the ride). A seemingly facile command over the sexual landscape of one’s partner is achieved without the encumbrances of clothes, coitus and the rest of the messy business. The blow job is, in essence, the new joystick of teen sexuality. (Salon)

Contrasted with:

When I was a teenager, in the bad-taste, disco-fangled ’70s, fellatio was something you graduated into. Rooted in the great American sport of baseball, the sexual metaphors of my generation put fellatio somewhere after home base, way off in the distant plains of the outfield. In fact, skipping all the bases and going directly to fellatio was the sort of home run reserved only for racy, borderline delinquents, who enjoyed a host of licentious and forbidden activities that made them stars in the firmament of teen recklessness.

March 22, 2024

Rome conquered Greece … militarily, anyway

In The Critic, Gavin McCormick reviews Charles Freeman’s new book The Children of Athena: Greek writers and thinkers in the age of Rome, 150BC – 400AD:

“To a wise man,” said the first-century wonderworker Apollonius of Tyana, “everywhere is Greece.” That is to say, Greece is not a mere place, but a special state of mind. For Apollonius, on his extensive travels around the Greco-Roman world, the purported truth of this maxim is seldom open to doubt.

The author of Apollonius’s colourful biography, Philostratus, depicts his hero as not just a philosopher but also an impossibly accomplished champion of culture — a confounder of logic and expectations who could vanish in plain sight, now fascinating Roman emperors and foreign sages, now inspiring whole towns into acts of celebration and renewal. The guiding ideology that drove this hero is a heady mix of philosophy, religion, magic and political insouciance — or, to give it another name, Hellenism.

In the context of the third-century world, where Christianity was an increasingly noteworthy presence in the towns and cities of the Roman empire, pagans such as Philostratus were keen to highlight what their own tradition had to offer.

In fact, he seems almost to present his hero as a pagan rival to Jesus. And, in turn, Apollonius — in his successful renewal of the shrines and local cults of Hellas — seems to hint at what Philostratus would like to see happen in his own contemporary context.

Despite living under Rome, Apollonius (and Philostratus) wants to celebrate an emphatically Greek form of culture. The celebration of Greek culture in the Roman world was, of course, nothing new, and it was something the Romans themselves had long enjoyed.

Alongside their admiration for Greek literature, philosophy, art and architecture, there was the successful movement known as the “Second Sophistic” — whose parade of Greek-speaking intellectuals left a heavy imprint on the public life of the High Roman Empire.

But it is striking nonetheless that the virtues of Hellas — not Rome itself — were what many educated citizens of the empire turned to when they thought of cultural renewal. Indeed his was precisely the route taken later in the fourth century by the last pagan emperor of Rome, himself a champion of all things Greek, Julian the so-called Apostate.

Charles Freeman’s latest book, Children of Athena, is a highly readable tour through the lives and accomplishments of some of the great exponents of Greek culture under Rome. He introduces readers to a bracingly varied and energetic cast of characters — the geographers, doctors, polymaths, botanists, satirists, and orators are just part of the repertoire. In an early chapter, we meet the brilliant Greek historian Polybius, who wrote in the tradition of Herodotus and Thucydides, while training his sights on the rise of Rome in his own time.

March 18, 2024

Life among the WEIRD

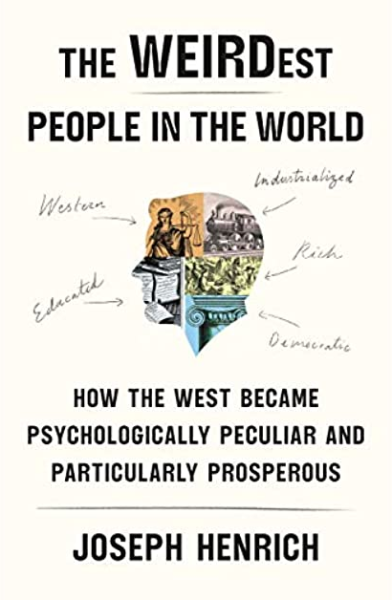

Rob Henderson reviews The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous by Joseph Henrich:

The word “WEIRD” stands for “Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic.” It is also a convenient way to communicate that people from such societies are psychologically different from most of the rest of the world and from most humans throughout history.

In short, the Western Church (Henrich’s term for the branch of Christianity that rose to power in medieval Europe) enacted a peculiar set of taboos, prohibitions, and prescriptions regarding marriage and family. This dissolved Europe’s kin-based institutions, and gave rise to a more individualistic psychology, which in turn spurred the creation of impersonal markets in which people grew used to interacting with and trusting unrelated strangers, and propelled the development of voluntary institutions, universally applicable laws, and innovation.

Characteristics of WEIRD people

WEIRD people are hyper-individualistic, self-obsessed, nonconformist, analytical, and value consistency. We try to be “ourselves” across social contexts and prize “authenticity”.

The book reviews research indicating that Americans rate those who show behavioral consistency during interactions in different contexts as more “socially skilled” and “likable” compared to those who are more behaviorally flexible. In contrast, non-WEIRD people view personal adjustments as reflecting social awareness and maturity.

In addition to valuing behavioral consistency, WEIRD people are more likely to feel guilt than shame. In contrast, non-WEIRD people are more likely to experience shame as opposed to guilt. Shame is the result of not living up to the expectations of one’s community. Guilt is a private emotion that results from falling short of our own expectations, rather than the community’s.

Relatedly, a recent study found that people can experience shame for being accused of actions they didn’t commit. The accusation alone was enough to elicit this powerful emotion. Shame is a reaction to others believing we did something bad rather than a reaction to actually doing something bad.

Delayed gratification also appears to be more prevalent in WEIRD societies. When researchers offered WEIRD people the choice between a smaller monetary payment up front, or a larger sum later, they tended to choose the larger sum. In contrast, most non-WEIRD people preferred the immediate, smaller, reward.

Interestingly Henrich relays data suggesting that greater patience is most strongly linked to positive economic outcomes in lower-income countries. Put differently, the tendency to defer gratification seems to be especially more important for economic prosperity in countries where formal institutions are less effective. This pattern holds within countries as well, such that patient people obtain higher incomes and more education. Patience is related to success after controlling for IQ and family income, and, even within the same families, more patient siblings obtain more education and higher earnings later in life.

Moreover, WEIRD people are more likely to adhere to rules even in the absence of external sanctions. The book reports that until 2002, U.N. diplomats from other countries were immune from having to pay parking tickets in New York City. Diplomats from the UK, Sweden, Canada, and other countries received a total of zero parking tickets. But diplomats from Bulgaria, Egypt, and Chad, among other non-WEIRD countries accumulated more than 100 tickets per member of their respective delegations. When diplomatic immunity was lifted, parking violations declined, but the gap between countries persisted.

But while they may be patient and rule-following, WEIRD people are more likely to be fair-weather friends. Relative to other populations, WEIRD people assign higher value to impartiality and show less favoritism toward friends, family members, and co-ethnics. We are more likely to abhor nepotism and believe in universally applicable principles.

March 16, 2024

Orwell – The New Life (DJ Taylor in discussion with Les Hurst)

The Orwell Society

Published Jun 9, 2023DJ Taylor discusses his new biography of Orwell with Les Hurst

Part 2:

The Orwell Society

Published Jun 26, 2023DJ Taylor answers questions and discusses issues raised by Orwell Society members.

March 15, 2024

Peter Turchin’s notion of the “overproduction of elites”

Severian is on a mini-vacation at the moment, but still managed to find time to share some thoughts about Turchin’s “overproduction of elites”:

University graduation – a large crowd of students at a graduation ceremony in Ottawa, Ontario. This was the thumbnail image used on the “Elite overproduction” Wikimedia page, which seemed quite appropriate.

Photo by Faustin Tuyambaze via Wikimedia Commons.

Let us consider “the overproduction of elites”. Those who love Peter Turchin’s work love this phrase, as it finally gives a name to a phenomenon we’ve all noticed: The creation, promotion, and indeed valorization of what would more properly be called social barnacles — they don’t move, can’t change, and eventually bring whatever they infest to a complete halt. Those who dislike his work often haven’t read it, so they object to the use of the word “elite” — again, these are social barnacles; what’s elite about them?

Which is precisely Turchin’s point — “elite” is a descriptor of their lifestyle, and most importantly their self-image; it is almost perfectly opposed to their actual utility. The modern Ed Biz is set up to do little else but produce these (pseudo) elites, and therefore a kind of Say’s Law takes hold. Say’s Law, you’ll recall, is vulgarly summarized as “Supply creates its own demand,” and that’s what we see with the (pseudo) elites churned out by every college in the land — they expect, indeed they demand, “jobs” commensurate with their “education”, and thus make-work “jobs” in the Apparat are brought into being.

They take out massive student loans to get the “jobs”; they “work” the “jobs” to service the debt, and so on.

But that’s true of most “white-collar” “jobs” these days. What separates the “elites”, in Turchin’s usage, from the rest of them is not their utility, or lack thereof — the economy, such as it is, would function just as well (or not) with far fewer lawyers, accountants, insurance adjusters, and so on. The difference, comrades, is what we must call Revolutionary Class Consciousness,

stealingnationalizingsocializingliberating a phrase from Lenin.An accountant, I’d wager, views his work as a technical specialty. They’re “rude mechanicals” (that’s Shakespeare, darlin’; evidently Mr. Ringo is an educated man). Maybe not so “rude” — accountants make good scratch; they’re middle to upper-middle class, economically — but basically technicians. Accounting is a highly-trained, well-compensated job, but that’s all it is: A job. Accounting is what an accountant does; it’s not what an accountant IS. Contrast that to the overproduced “elites”, in Turchin’s sense, and you see what Turchin’s sense really means: An “elite” really IS his job title.

Note the shift: His job title. As we all know, so many of the overproduced “elite” do no meaningful work. How could they? We could easily do this for most any “job” in the Apparat, but one example will suffice. Consider “Journalist”. Formerly called “Reporter”, and back then it required some actual productive output. Some “shoe leather”, as the phrase was. To find out what they were up to at City Hall, you actually had to physically go down to City Hall and follow the Mayor around. These days — the days when Reporters are now Journalists — it’s just stenography. And not even real stenography, Claudine Gay-style stenography — the Mayor’s press secretary (who probably went to college with you) emails you a press release; you change a word or two and then reprint it, basically verbatim, under your byline.

A monkey could be trained to do it. Hell, a chatbot could be trained to do it, and that’s probably a good quick-and-dirty definition of a Turchin-style overproduced “elite”: If whatever “work” he does could easily be replaced by a chatbot, with no appreciable drop-off in either productivity or quality. Because that’s the key to understanding these people: They know damn good and well, at some almost-but-not-quite conscious level, that they’re social barnacles. That is the “base” upon which the “superstructure” — again stealing terms from Onkel Karl — of their Revolutionary Class Consciousness is built.

March 14, 2024

Book Reviews – Juno Beach and the Canadians

WW2TV

Published Dec 5, 2023A short live show where I talk about my favourite Juno Beach and Canadian focussed Normandy books

WW2TV Bookshop – where you can purchase copies of books featured in my YouTube shows. Any book listed here comes with the personal recommendation of Paul Woodadge, the host of WW2TV. For full disclosure, if you do buy a book through a link from this page WW2TV will earn a commission.

UK – https://uk.bookshop.org/shop/WW2TV

USA – https://bookshop.org/shop/WW2TV

March 12, 2024

QotD: Isaiah Berlin on Niccolò Machiavelli

When asked about Machiavelli’s reputation, people use terms like “amoral”, “cynical”, “unethical”, or “unprincipled”. But this is incorrect. Machiavelli did believe in moral virtues, just not Christian or Humanistic ones.

What did he actually believe?

In 1953, the British philosopher Isaiah Berlin delivered a lecture titled “The Originality of Machiavelli”.

Berlin began by posing a simple question: Why has Machiavelli unsettled so many people over the years?

Machiavelli believed that the Italy of his day was both materially and morally weak. He saw vice, corruption, weakness, and, as Berlin says, “lives unworthy of human beings”. It’s worth noting here that around the time that Machiavelli died in 1527, the Age of Exploration was just kicking off, and adventurers from Italy and elsewhere in Europe were in the process of transforming the world. Even the shrewdest individuals aren’t always the best judges of their own time.

So what did Machiavelli want? He wanted a strong and glorious society. Something akin to Athens at its height, or Sparta, or the kingdoms of David and Solomon. But really, Machiavelli’s ideal was the Roman Republic.

To build a good state, a well-governed state, men require “inner moral strength, magnanimity, vigour, vitality, generosity, loyalty, above all public spirit, civic sense, dedication to security, power, glory”.

According to Machiavelli, these are the Roman virtues.

In contrast, the ideals of Christianity are “charity, mercy, sacrifice, love of God, forgiveness of enemies, contempt for the goods of this world, faith in the hereafter”.

Machiavelli wrote that one must choose between Roman and Christian virtues. If you choose Christianity, you are selecting a moral framework that is not favorable to building and preserving a strong state.

Machiavelli does not say that humility, compassion, and kindness are bad or unimportant. He actually agrees that they are, in fact, good and righteous virtues. He simply says that if you adhere to them, then you will be overrun by more unscrupulous men.

In some instances, Machiavelli would say, rulers may have to commit war crimes in order to ensure the survival of their state. As one Machiavelli translator has put it: “Men cannot afford justice in any sense that transcends their own preservation”.

From Berlin’s lecture:

If you object to the political methods recommended because they seem to you morally detestable … Machiavelli has no answer, no argument … But you must not make yourself responsible for the lives of others or expect good fortune; you must expect to be ignored or destroyed.

In a famous passage, Machiavelli writes that Christianity has made men “weak”, easy prey to “wicked men”, since they “think more about enduring their injuries than about avenging them”. He compares Christianity (or Humanism) unfavorably with Paganism, which made men more “ferocious”.

“One can save one’s soul,” writes Berlin, “or one can found or maintain or service a great and glorious state; but not always both at once.”

Again, Machiavelli’s tone is descriptive. He is not making claims about how things should be, but rather how things are. Although it is clear what his preference is.

He writes that Christian virtues are “praiseworthy”. And that it is right to praise them. But he says they are dead ends when it comes to statecraft.

Machiavelli wrote:

Any man who under all conditions insists on making it his business to be good, will surely be destroyed among so many who are not good. Hence a prince … must acquire the power to be not good, and understand when to use it and when not to use it, in accord with necessity.

To create a strong state, one cannot hold delusions about human nature:

Everything that occurs in the world, in every epoch, has something that corresponds to it in the ancient times. The reason is that these things were done by men, who have and have always had the same passions.

Rob Henderson, “The Machiavellian Maze”, Rob Henderson’s Newsletter, 2023-12-09.