Kulak takes on politics and violence:

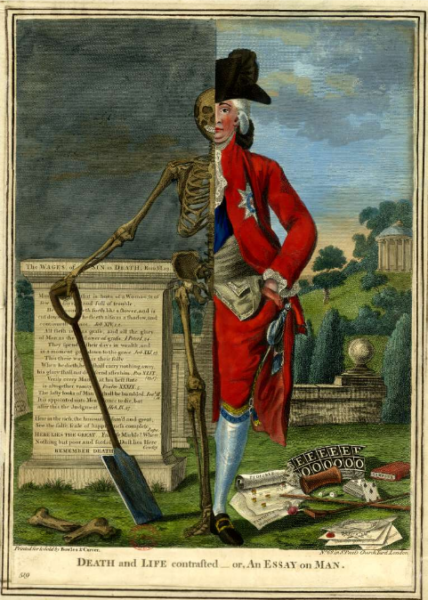

“Death and Life constrasted … or, an Essay on Man” by Robert Dighton, 1784.

British Museum number 1935,0522.3.55.

The power of any law comes from the fact that armed men stand ready to commit an escalating series of violence against those who do not comply. And even the lightest touch, subtlest “Nudge” laws gain their power via subtly manipulating the circumstances in which violence by state is already applied. (When you fill out the tax form you must fill out or be dragged to prison, this new law will let you fill in a box to receive $200 back if you have a dog … whom the IRS would shoot before taking you to prison if you had not surrendered the money to them in the first place)

To say someone has political power whether a voter, an activist, or a politician … is to say they can effect political outcomes such that they can make violence more or less likely to be exercised against someone.

If your political activism and activity is not connected to any mechanism to commit violence, whether through the states agents, or through an illegal organization … you are not a political actor. You are a “citizen”, “voter”, “activist”, “politician” in the same way the madman at the asylum is “Napoleon”, you may play-act with the symbols of power … but you do not interact with it.

All Political Discussion Terminates in Violence

All discussions of politics is inevitably, and CAN ONLY BE, a conspiracy to commit violence, whether legally through the state, illegally through some form of direct action or “terrorism”, or Stochastically through some impact on the culture or wider discussion which will make the prior two more likely or effect their nature.

If your supposedly political speaking’s have no connection to state or non-state “policy” Ie. Violence … then they are not political. You are engaged in fantasy at best, grovelling at worst.

This is why so many in the safety brigade and regime are not incorrect when they call the political speech of their opponents “Dangerous” or a form of “violence” all political speech is necessarily, by the nature of being political, directed to altering the atmosphere, calculus, mechanisms, and willing committal of state and non-state violence.

.

None of this should be shocking

Clausewitz observed “War is politics by other means”

Vladimir Lenin observed the inverse: “Politics is warfare by other means”

In both they merely restated Hobbes: The state of nature is a state of war and peace is merely an artifice mutually consented to by all sides under a sovereign … which can be unilaterally terminated at will by any party, and rationally must be terminated in any one of a thousand circumstances.

That Rights and Liberties are “Given by God” is a euphemism for the violence and threat implicit in the claims of free men.

The founders saying their rights were “endowed by God”, was no different than Carolus Rex declaring he was “Chosen by Heaven” … It was a euphemism and a flex that their violence and dominance of fate had left them masters of their domain, and that they’d meet any challenge with as much violence as a crusader or Inquisitor would visit upon a heretic challenger.