After the riots were over, the government appointed a commission to enquire into their causes. The members of this commission were appointed by all three major political parties, and it required no great powers of prediction to know what they would find: lack of opportunity, dissatisfaction with the police, bla-bla-bla.

Official enquiries these days do not impress me, certainly not by comparison with those of our Victorian forefathers. No one who reads the Blue Books of Victorian Britain, for example, can fail to be impressed by the sheer intellectual honesty of them, their complete absence of any attempt to disguise an often appalling reality by means of euphemistic language, and their diligence in collecting the most disturbing information. (Marx himself paid tribute to the compilers of these reports.)

I was once asked to join an enquiry myself. It was into an unusual spate of disasters in a hospital. It was clear to me that, although they had all been caused differently, there was an underlying unity to them: they were all caused by the laziness or stupidity of the staff, or both. By the time the report was written, however (and not by me), my findings were so wrapped in opaque verbiage that they were quite invisible. You could have read the report without realising that the staff of the hospital had been lazy and stupid; in fact, the report would have left you none the wiser as to what had actually happened, and therefore what to do to ensure that it never happened again. The purpose of the report was not, as I had naively supposed, to find the truth and express it clearly, but to deflect curiosity and incisive criticism in which it might have resulted if translated into plain language.

Theodore Dalrymple, “It’s a riot”, New English Review, 2012-04.

April 13, 2023

QotD: The real purpose of modern-day official commissions

April 12, 2023

Institutional Review Boards … trying to balance harm vs health, allegedly

At Astral Codex Ten Scott Alexander reviews From Oversight to Overkill by Simon N. Whitley, in light of his own experience with an Institutional Review Board’s demands:

Dr. Rob Knight studies how skin bacteria jump from person to person. In one 2009 study, meant to simulate human contact, he used a Q-tip to cotton swab first one subject’s mouth (or skin), then another’s, to see how many bacteria traveled over. On the consent forms, he said risks were near zero — it was the equivalent of kissing another person’s hand.

His IRB — ie Institutional Review Board, the committee charged with keeping experiments ethical — disagreed. They worried the study would give patients AIDS. Dr. Knight tried to explain that you can’t get AIDS from skin contact. The IRB refused to listen. Finally Dr. Knight found some kind of diversity coordinator person who offered to explain that claiming you can get AIDS from skin contact is offensive. The IRB backed down, and Dr. Knight completed his study successfully.

Just kidding! The IRB demanded that he give his patients consent forms warning that they could get smallpox. Dr. Knight tried to explain that smallpox had been extinct in the wild since the 1970s, the only remaining samples in US and Russian biosecurity labs. Here there was no diversity coordinator to swoop in and save him, although after months of delay and argument he did eventually get his study approved.

Most IRB experiences aren’t this bad, right? Mine was worse. When I worked in a psych ward, we used to use a short questionnaire to screen for bipolar disorder. I suspected the questionnaire didn’t work, and wanted to record how often the questionnaire’s opinion matched that of expert doctors. This didn’t require doing anything different — it just required keeping records of what we were already doing. “Of people who the questionnaire said had bipolar, 25%/50%/whatever later got full bipolar diagnoses” — that kind of thing. But because we were recording data, it qualified as a study; because it qualified as a study, we needed to go through the IRB. After about fifty hours of training, paperwork, and back and forth arguments — including one where the IRB demanded patients sign consent forms in pen (not pencil) but the psychiatric ward would only allow patients to have pencils (not pen) — what had originally been intended as a quick record-keeping had expanded into an additional part-time job for a team of ~4 doctors. We made a tiny bit of progress over a few months before the IRB decided to re-evaluate all projects including ours and told us to change twenty-seven things, including re-litigating the pen vs. pencil issue (they also told us that our project was unusually good; most got >27 demands). Our team of four doctors considered the hundreds of hours it would take to document compliance and agreed to give up. As far as I know that hospital is still using the same bipolar questionnaire. They still don’t know if it works.

Most IRB experiences can’t be that bad, right? Maybe not, but a lot of people have horror stories. A survey of how researchers feel about IRBs did include one person who said “I hope all those at OHRP [the bureaucracy in charge of IRBs] and the ethicists die of diseases that we could have made significant progress on if we had [the research materials IRBs are banning us from using]”.

Dr. Simon Whitney, author of From Oversight To Overkill, doesn’t wish death upon IRBs. He’s a former Stanford IRB member himself, with impeccable research-ethicist credentials — MD + JD, bioethics fellowship, served on the Stanford IRB for two years. He thought he was doing good work at Stanford; he did do good work. Still, his worldview gradually started to crack:

In 1999, I moved to Houston and joined the faculty at Baylor College of Medicine, where my new colleagues were scientists. I began going to medical conferences, where people in the hallways told stories about IRBs they considered arrogant that were abusing scientists who were powerless. As I listened, I knew the defenses the IRBs themselves would offer: Scientists cannot judge their own research objectively, and there is no better second opinion than a thoughtful committee of their peers. But these rationales began to feel flimsy as I gradually discovered how often IRB review hobbles low-risk research. I saw how IRBs inflate the hazards of research in bizarre ways, and how they insist on consent processes that appear designed to help the institution dodge liability or litigation. The committees’ admirable goals, in short, have become disconnected from their actual operations. A system that began as a noble defense of the vulnerable is now an ignoble defense of the powerful.

So Oversight is a mix of attacking and defending IRBs. It attacks them insofar as it admits they do a bad job; the stricter IRB system in place since the ‘90s probably only prevents a single-digit number of deaths per decade, but causes tens of thousands more by preventing life-saving studies. It defends them insofar as it argues this isn’t the fault of the board members themselves. They’re caught up in a network of lawyers, regulators, cynical Congressmen, sensationalist reporters, and hospital administrators gone out of control. Oversight is Whitney’s attempt to demystify this network, explain how we got here, and plan our escape.

French Onion Soup from 1651

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 11 Apr 2023

(more…)

Omnipolitization, the scourge of the western world

Theophilus Chilton, reposting from 2018 (!), explains why the inexorable spread of government everywhere in the west has led us to a situation where every election is “the most important election in history”, and every government decision can infringe upon or even ruin the lives of millions of people as mere side-effect:

The western front of the United States Capitol. The Neoclassical style building is located in Washington, D.C., on top of Capitol Hill at the east end of the National Mall. The Capitol was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Politics in the United States have become an all-encompassing nightmare from which the average American cannot hope to escape. As American democracy (you know, the “freedom” form of government) expands the reach of the managerial state into every area of modern life, the stakes involved in the political process have mushroomed, with control over the lives of hundreds of millions of people hanging in the balance. It’s little surprise that each election season stretches out over a year, and (as Florida and Georgia recently showed us) doesn’t end once the voting is “officially” over.

It’s reached the point where literally everything is involved in some way with politics. Your choice of restaurant now signals your political inclinations, and thus who will harass you while eating there. Businesses themselves feel compelled to virtue signal, usually in a leftward direction, lest they bring upon themselves threats of boycott, bad publicity, or worse. It has escalated to the point where being the public face of the “wrong” side earns you harassment and menace to your physical health, as Tucker Carlson and several Republican members of Congress have found out. Expressing the “wrong” opinions in the workplace or online can get you reprimanded or fired.

How did we reach that point?

It hearkens back to something I wrote about earlier concerning the tyranny of the technical society. In our particular case, we are seeing a situation playing out in real time whereby “political techniques” first pioneered by Lenin in establishing and maintaining Soviet control over Russia are being used to bring every facet of modern life into the political realm. Every action and attitude has a political ramification which can affect your employment, your access to social amenities, and even (eventually) your freedom from the gulag.

This omnipolitisation leads inevitably into a dichotomy between formal and informal power in the US governing system. Formal power is exactly as it sounds – the “constitutional” (written or otherwise) distribution of decision and policy-making authority in a government, i.e. which entity or body gets to legally do what. This usually involves theoretical limits on the roles or extent of governing authority, which sets it in opposition to the principle of omnipolitics. Conversely, informal power is also exactly as it sounds – it is power wielded extra-constitutionally (yet in a very real sense) by those who “shouldn’t” be exercising it, but nevertheless are.

Miniature Railway (1959)

British Pathé

Published 13 Apr 2014Romney, Kent.

L/S of a lovely looking train locomotive. A man stands next to it and one realises how small the train is. It is one third of an ordinary train size — says voiceover. However, this is not a toy but a regular public railway, smallest in the world. It is officially known as the Romney Hythe and Dymchurch Railway, it runs between Romney and Dungeness and its passengers are children. This tiny railway must conform to the same Ministry of Transport regulations as any other trains. M/S of a driver Mr Bill Hart, checking the train. C/U shot of a plaque reading “Winston Churchill”. This is the engine’s name. Several shots of Mr Hart checking the train. Mr Hart enters his cabin and starts shovelling coal into the boiler. C/U shot of the coal being thrown in and a little door closed. This train takes one third of the coal needed for a regular size train. The train starts moving.

L/S of the two men turning locomotive on turntable to place it on rails. M/S of a woman cleaning windows along the train. Children arrive and station master, Reg Marsh, directs them to their coaches. M/S of the group of girls entering the train. M/S of the station master Mr Marsh blowing a whistle as a sign that train leaves the station. M/S of an elderly man looking at a huge pocket watch on a chain, and afterwards, in direction of the train. He is Captain Howey, a man responsible for having the line built. C/U shot of the watch — Roman numerals. M/S of Mr Howey as he puts the watch in his pocket. C/U shot of Mr Howey’s face.

M/S of the little train moving. C/U shot of its little chimney with a smoke coming out. M/S of the Rose family from Sanderstead, Surrey with their dog Trixie enjoying the ride C/U shot of driver’s face with the smoke covering it up to the point it becomes invisible. Another little train passes it going in different direction. Several shots of the two little trains moving. A car stops to wait for the train to pass. L/S of the little train as it approaches the station.

Note: Another driver appearing in the film is Peter Catt. Combined print for this story is missing.

(more…)

QotD: Karen

Back in March, I was certain this whole thing [the pandemic] would blow over in a matter of weeks. It’s a Karen-driven phenomenon, I argued, but unlike everything everything else they do, this time Karen’s going to have to shoulder the burden herself. She’ll have fun berating the manager of the local Starbucks for not closing down … until she realizes there’s no place to get a half-caff, triple-foam, venti soy latte frappuccino. Nor is there any place to dump her

self-propelled lifestyle accessorieskids while she gets exalted at hot yoga and the nail salon, now that school’s out. Give her a week without Starbucks, I said, locked in her house with Kayden, Brayden, Jayden, and Khaleesi, and she’ll demand we never mention the word “flu” again.In other words, I misunderstood the essence of Karen. Karen is — first, foremost, and always — a victim. I of all people should’ve known better, because I was surrounded by Karens all the time in my personal and professional life. I’ve mentioned this story before, but bear with a quick repeat: At one of my first teaching gigs, at the big directional tech that makes up a lot of “Flyover State”, the department’s women got it into their vapid little heads that they — women — were being systematically excluded from positions of power. The fact that the department chair was a woman, and in fact the whole department, emeritus through first year grad student, was something like 65% female should’ve been their first clue, but nevertheless, they persisted. They got together a blue-ribbon commission, as one does, and studied the shit out of the problem. The much-ballyhooed report revealed …

… that all the positions of authority in the department, every blessed one, was held by a female. At which point, without missing a single fucking beat, they started complaining that being forced to hold all these positions of authority was keeping them from making adequate career progress.

I shit you not.

That’s Karen, my friends.

Severian, “The Civil War That Wasn’t”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-09-09.

April 11, 2023

Canada’s colonial past

Peter Shawn Taylor talks to Nigel Biggar, author of the recent book Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning:

C2C Journal: Explain what you mean by a “moral reckoning” for colonialism – and how does that differ from the now-standard historians’ view that it was a shameful era characterized by exploitation, racism and violence?

Nigel Biggar: My first degree from Oxford is in history but professionally I am a theologian and ethicist. An ethicist is in the business of thinking about rights and wrongs and complicated moral issues. As I have previously written about the morality of war, I wanted to bring that ethical expertise to the very complicated historical phenomenon of empire.

And while my critics claim I am not an historian, they are not ethicists. My book is not a chronology. Each chapter deals with a different moral issue: motives, violence, racism, slavery, et cetera. Then I try to bring it to a conclusion with an overall view of the record of British imperialism, morally speaking. There are the evils of the British Empire, and there are its benefits as well.

[…]

C2C: One of your chapters takes a close look at Canada’s Indian Residential Schools. Take us through an ethicist’s view of a topic that has come to be considered this country’s greatest sin.

NB: The motivation for establishing residential schools was basically humanitarian. That is, they were meant to enable pupils to survive in a world that was changing radically. Notwithstanding any abuses and deficiencies that may have come later, we have to deal with the fact that native Canadians were asking for these schools in the beginning. They lobbied for them in treaties. And this was because they recognized that for their people to survive, they needed to adapt. They wanted their young people to learn English or French and how to farm. They recognized that the old ways could not be sustained any longer.

A lot of people today have a hard time coming to grips with the fact that the past was a very different place. For most people, the 19th century was pretty damn brutal. When we consider the conditions in residential schools today, we are horrified. But what is horrifying are the conditions in which most people of that time had to live. It is true mortality among native kids in these schools was generally higher and conditions were poorer. Sexual abuse was also a problem, but mostly by fellow pupils. I don’t want to sweep any of that under the table. Maybe the Canadian government should have spent more money on residential schools. But to make that case you need to identify what the government of the day should have spent less on. And I haven’t seen that argument made anywhere.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has many lurid tales about kids being seized from their parents. No doubt that, after education became compulsory in the 1920s, some children were distressed at being taken away. But this too has to be understood in light of the fact that the idea all children must have a certain level of education was gaining tremendous traction in Canada, Britain and throughout Europe at this time. So compulsory education for native children must be considered in that regard. And what might people say today if the Government of Canada had refused to educate Indigenous children?

Again, I don’t want to downplay the defects of residential schools. But we need to provide context in order to understand these things in proportion. It must also be considered significant that since the early 1990s, Canadian media have declined to give voice to many natives who want to offer positive expressions of residential schools, as J.R. Miller points out in his authoritative history of the residential school system, Shingwauk’s Vision. According to Miller, the verdict for the schools must be given in “muted and equivocal terms”. The wholesale damnation of residential schools is overwrought and unfair.

The amplifier may have been the key technological innovation that let vocalists and guitarists become stars

Chris Dalla Riva, guest-posting at Ted Gioia’s Honest Broker, considers how instrumental hits used to be far more popular before (among other factors) microphone technology let vocalists compete with orchestras and guitar amplifiers let the strings dominate the pop music market:

Clarinet players aren’t sex symbols. I say this with no disrespect for those that play the single-reeded woodwind. But if you asked a random person on the street to name a clarinet player, I suspect most people couldn’t come up with one, let alone one known for their good looks. Then again, this isn’t a particular indictment of clarinetists. If you asked that same person to name a sexy musician, I’d bet a large sum of money they’d name a vocalist.

This wasn’t always the case, though. In Kelly Schrum’s book Some Wore Bobby Sox: The Emergence of Teenage Girls’ Culture, 1920-1945, she notes that in high school yearbooks in the 1930s some students expressed a passion for “Benny Goodman while other girls had a ‘weakness’ for Artie Shaw or were classified as Glenn Miller ‘fanatics’, faithful fans of Tommy Dorsey, or ‘Happy while listening to Kay Kyser’. Cab Calloway, Xavier Cugat, and Harry James were also popular favorites.” Of those musicians, only Calloway was a singer. Goodman, Shaw, and Kyser played the clarinet. Miller and Dorsey played the trombone. Cugat played violin. James played trumpet.

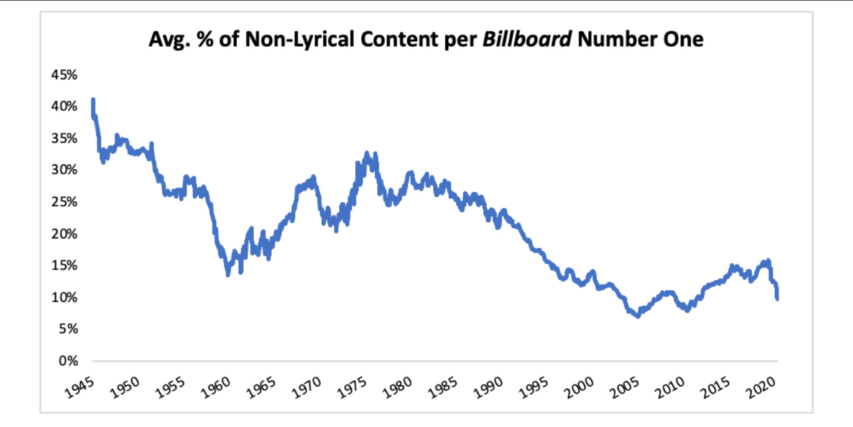

Given that our contemporary musical world is dominated by vocalists, this seems bizarre. It feels like if you have a musical group it must be centered around the vocalist. If we measure the average percent of instrumental content per Billboard number hit between 1940 and 2021, we see demonstrable evidence for not just the decline of the instrumental superstar but the instrumentalist generally, with the sharpest declines beginning in the 1950s and the 1990s.

NOTE: Data from July 1940 to August 1958 comes from Billboard‘s Best Sellers in Stores chart. After August 1958, Billboard deprecated that chart in favor of the Hot 100, which initially aggregated sales, jukebox, and radio data. The Hot 100 remains the premiere pop chart, though it has come to include many more sources, like streams and digital downloads. The above displays a 50-song rolling average.

What’s going on here? How could throngs of high schoolers long for the clarinet-wielding Artie Shaw 80 years ago when most teenagers today would struggle to name a musician who isn’t also a singer. I believe it comes down to four factors: improved technology, the 1942 musicians’ strike, WWII, television, and hip-hop.

Improved Technology

In the VH1-produced documentary The Brian Setzer Orchestra Story, Dave Kaplan, Setzer’s manager, recounts a conversation he had with Setzer before assembling a guitar-fronted big band in the 1990s: “Nobody had ever fronted a big band with an electric guitar … I asked Brian, ‘Why wouldn’t somebody have tried it?’ [Setzer replied,] ‘Well there weren’t amps.'” Albeit a simplification, Setzer’s quip is pretty accurate.

While there were some famous guitar players among the big bands of the first half of the 20th century, we don’t see the guitar become a driving force in popular music until amplification improved. This was not only a boon for the guitarists but also vocalists. Unlike brass and wind instruments, you can sing while you play the guitar. Thus, it’s not shocking that the rise of the guitar coincided with the rise of the vocalist.

But it wasn’t just guitar amplification technology that was vital. It was also microphone technology. Again, microphones had to improve so vocalists could compete with the cacophony of a loud band. On top of this, recording had to change to capture more subtlety in the human voice.

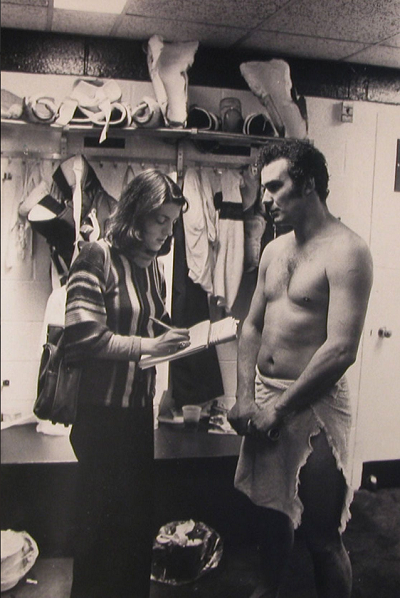

The end of single-sex spaces began in the 1970s, at least for men

Janice Fiamengo points out that the initial loss of single-sex spaces began a long time ago and for what — at the time — seemed sensible and egalitarian reasons:

Robin Herman of the New York Times was one of the first two female reporters ever allowed into NHL dressing rooms, starting with the 1975 NHL All-Star Game in Montreal.

There has been a good deal of talk lately about women’s spaces being invaded by biologically male persons identifying as women. Some women’s campaigners claim that the trans phenomenon constitutes an attack on womanhood itself, an attempt to “erase” women and replace them with men who perform womanhood. Some even call it a new form of patriarchy.

But well before women had their single-sex spaces threatened, something similar had already happened to men. Beginning in the 1970s, men’s spaces were usurped, their maleness was denigrated, and policies and laws forced changes in male behavior that turned many workplaces into feminized fiefdoms in which men held their jobs only so long as women allowed them to. The very idea of an exclusively male workspace or club — especially if it was a space for socializing (not so much if it was a sewer, oil field, or shop floor in which men did unpleasant, dangerous work) — came to be seen as dangerous. In light of the recent furor over single-sex spaces for women, it is useful to consider the source of some men’s justifiable apathy and resentment.

At my new academic job in the late 1990s, a woman who had been the first female historian hired into her department used to tell a story she’d had passed on to her from a male colleague. After the decision had been made to hire her, one of the historians said to another somewhat dolefully, “I guess that’s the end of our meetings in the urinal.” The joke ruefully acknowledged, and good-naturedly accepted, the end of their all-male work environment.

Though this woman didn’t have any trouble with her male colleagues, who welcomed her civilly, she told the story with an edge of contempt. Even thoroughly modern men, the story suggested, held a foolish nostalgia for pre-feminist days.

But was it foolish — or did the men recognize something real?

No one thought seriously, then, about the disappearance of men’s single-sex spaces. The idea that men and boys need places where they can be with other men (defended, for example, in Jack Donovan’s The Way of Men) would have been cause, amongst the women I knew, for scornful laughter. In 2018, anti-male assumptions had become so deeply entrenched that the female author of a Guardian article titled “Men-only clubs and menace: how the establishment maintains male power” simply could not believe that any decent man could legitimately seek out male-only company.

Under the circumstances of mixed groups of reporters crowding into team locker rooms after games, it’s rather surprising how few “towel malfunction” incidents have been reported.

LeMat Centerfire Pistol and Carbine

Forgotten Weapons

Published 27 Nov 2014Colonel LeMat is best known for his 9-shot muzzleloading .42 caliber revolver with its 20 gauge shot barrel acting as cylinder axis pin — several thousand of these revolvers were imported and used in the field by Confederate officers during the US Civil War (and modern reproductions are available as well). What are less well-known are the pinfire and centerfire versions of LeMat’s revolver, and the carbine variants as well.

In this video I’m taking a look at a centerfire LeMat revolver and a centerfire LeMat carbine, both extremely rare guns. They use the same basic principles as the early muzzleloading guns, but look quite different. In these guns, the shotgun remains 20 gauge but uses a self-contained shell loaded from the rear, and the 9 rifles shots are designed for an 11mm (.44 caliber) cartridge very similar to that used in the French 1873 service revolver.

(more…)

QotD: Being the target of a death threat

It is now about fourteen months since, after receiving my second death threat, I started carrying a firearm almost constantly. This experience has taught me a few truths, some merely amusing but others with larger implications.

[…]

And about that security plan: carrying a firearm is nearly useless without very specific kinds of mental preparation. It’s not just that you have to think through large ethical issues about when to draw and when to fire (equivalently, when to threaten lethal force and when to use it). You also need good defensive habits of mind. Carrying a firearm is no good if an adversary wins the engagement before you have time to draw.

The most basic good habit of mind is maintaining awareness of your tactical environment. From what directions could you be attacked? Is there a way for an assailant to come up behind you for a hand-to-hand assault, or to line up a shooting position from beyond hand-to-hand range where you couldn’t see it? Are you exposed through nearby windows?

One advantage I had going in was reading Robert Heinlein as a child. This meant I soaked up some basic tactical doctrine through my pores. Like: when you go to a restaurant, sit with your back to a wall, preferably in a corner, in a place with good sightlines but not near a window. When you sit down, think about possible threat axes and which direction to bail out in if you have to.

Advice I’ve gotten from people with counterterrorism training includes this lesson: watch your environment and trust your instincts. Terrorists, criminals, and crazies don’t tend to blend in well even when they’re trying. If someone nearby looks or feels out of place in your surroundings, or behaves in a way not appropriate to the setting, pay attention to that; check your escape routes and make sure you can reach your weapons quickly.

How careful you have to be depends on the threat model you’re planning against. I’m not going to talk about mine in detail, because that might compromise my security by telling bad guys what expectations to game against. But I will say that it assigns a vanishingly small probability to professionals with scoped rifles; the background culture of both Iranian terrorists and their Arab proxies makes it extremely difficult for them to train or recruit snipers, and I am reliably informed that the Iranians couldn’t run professional hit teams in the U.S. anyway – too difficult to exfiltrate them, among other problems.

This, along with some other aspects of the threat model I won’t discuss, narrows the range of plausible threats to something an armed and trained individual with good backup from law enforcement has a reasonable hope to be able to counter. And the good backup from law enforcement is not a trivial detail; real life is not a Soldier of Fortune story or a running-man thriller, and a sane security plan uses all the resources available from your connections to the society around you.

Eric S. Raymond, “Fourteen months of carrying”, Armed and Dangerous, 2010-09-21.

April 10, 2023

It’s totally normal for a country to send troops overseas and neglect paying to feed them, right?

This week’s Dispatch post from The Line includes some commentary on the story I linked to last week from the Ottawa Citizen, reporting that Canadian soldiers sent to Poland to train Ukrainian troops are being stiffed by the Department of National Defence on their food bills:

Operation Unifier shoulder patch for Canadian troops in Ukraine.

Detail from a photo in the Operation Unifier image gallery

Here’s a totally normal story from a well-functioning country that isn’t at all broken: it turns out that processing per diems for a hundred or so folks is now beyond the capability of the federal government.

This story came to us courtesy the Ottawa Citizen, where David Pugliese reported that the company sized unit of Canadian military personnel operating in Poland has seen months worth of expense filings go unpaid. In some situations, a military unit sent abroad would include its own logistical support team, including cooks. In other situations, a relatively small unit sent to a place with functioning civilian infrastructure is told to feed themselves and keep the receipts for reimbursement. For our troops in Poland, there to provide logistical and training support to Ukrainian forces since October, the government went the latter route.

And that’s fine. Really. Frankly, we’re sure the troops are happier eating out at local places and enjoying delicious Polish food — really, it’s amazing — than getting three servings of military slop a day. The problem, though, as these poor troops discovered, is that the military and national defence bureaucracy no longer has the ability to process the expense payments. So these balances are just sitting on their personal credit cards. For months.

[…]

The mission began in October.

It seems almost pointless to add much actual insight and analysis here. This kind of dysfunction speaks for itself. We’ll limit ourselves to two comments: operational deployments are incredible stressful on military personnel and their families on the homefront. That’s uncontroversial, and unavoidable. That’s why military service is recognized as a sacrifice even during peacetime deployments. The basic bargain we make with our servicemembers is while they are serving their country abroad, their country will take care of their families at home. Leaving these families with high-interest credit-card balances they can’t pay off because the Canadian government is too broken to reimburse soldiers for expenses they were told to incur is an on-the-nose failure of Canada to honour its debt to the the military parents, spouses and children who have been, in effect, ordered to advance the Canadian government money to subsidize military deployments.

The second comment we’ll make, is that this isn’t just further evidence in support of the Canada-is-broken thesis — it’s a very specific kind of break. We’ve all known that Canadian governments, at all levels, have struggled to turn new policies into new programs. That’s not new. But even granting that failure, we’ve generally been able to keep doing the things we already do. There seemed to be enough residual muscle memory in our governments. Can we do new things? No, not really. But we’ll keep doing the stuff we already do.

This military fiasco is alarming because it’s a sign that our state-capacity issues are now extending into areas that previously worked. Not only are we struggling to do new things, we’re forgetting how to do things we used to be able to do. This goes beyond what our typical gripes about state capacity. This is something else. This is state atrophy, or rot.

Now that the public is paying attention, we suspect we’ll see some reasonably rapid progress. The government will throw bureaucrats and maybe consultants at the problem until it goes away. This is how they have reacted to similar issues: we hurled ground staff at airport delays until they cleared, and bureaucrats at passport offices until the backlogs eased.

But we have to ask why we now require exceptional redeployments of staff to maintain typical levels of service. And we don’t like the answers we can come up with. Ottawa has added tens of thousands of civil servants, at an annual cost of tens of billions, in recent years. During that time Ottawa has also sharply ramped up spending on consultants; the annual cost now surpasses $20 billion.

And yet.

What the hell is going on?

I’ve been saying for literally years now, the more the government tries to do the less well it does everything, and this fiasco is a perfect example of that sclerosis spreading further.

The ADL would like to warn you away from that dangerous source of information, Substack

Chris Bray doesn’t seem to be taking the ADL’s dire warnings seriously here:

The ADL has written a much-discussed hit piece about Substack …

Substack, a subscription-based online newsletter platform for independent writers, continues to attract extremists and conspiracy theorists who routinely use the site to profit from spreading antisemitism, misinformation, disinformation and hate speech.

… and I’m grateful. It’s gloriously stupid and clumsy, and shows how the braindead disinformation racket works. If you read Jacob Siegel’s important examination of the disinformation hoax in Tablet, and then read the ADL’s laugh-out-loud stupid article about Substack, you’ll be inoculated. You’ll be a dead end for this mind virus. See, this discussion is a vaccine, and that means it’s good and you can’t ever question it.

Start with the headline:

So the opening claim, the frame the headline establishes as you wade into the text, is that this is an exposé of antisemitism, of people — like Nazis! — who hate Jews. Substack is a Nuremberg rally, y’all, and Leni Riefenstahl has the film rights. The topic of the piece is hate and bigotry. And then the text says things like this:

1.) Antisemitism is on Substack!

2.) For example, Steve Kirsch criticizes Covid vaccines.

Pretty sure Steve Kirsch is Jewish, by the way, and listed alongside other monsters who publish on the Jew-hating platform Substack. Also a vicious hater writing on the antisemitic platform, as the ADL warns us: Chaya Raichik (of Libs Of TikTok fame), an orthodox Jew. I’m not a technical expert, but this may be poor form for antisemitic publishing. “Anti-Papist mob to publish G.K. Chesterton box set”.

The lumping in of this thing, this thing, and this entirely other thing is a way to dirty up a bunch of Not X by reference to X, warning about antisemitism at the top and then delivering text about people who criticize pharmaceutical products. This website hosts people who love terrorism, genocide, and baking. For example, cupcakes.

Second, and this amazes me, the ADL piece — in 2023! — runs on the premise that the line between good information and dangerous disinformation is perfectly clear and eternally unchanging. Steve Kirsch writes “anti-vaccine conspiracy theories”. See, and not one of those have ever proved to be true. What we think is true now about mRNA vaccines in the spring of 2023 is exactly what we believed in March of 2020. Truth never changes, and no ambiguity ever exists in any scientific question. No debate is ever real or reasoned. No skeptic has ever turned out to be right about anything, ever, on any topic in any field, like eugenics and phrenology. This narrative approach, the rhetorical equivalent of watching a writer hit himself in his own drooling face with a boot, is why every person of ordinary good sense sighs heavily at the first sign that someone claims status as a disinformation expert.

The Crimean Naval War at Sea – Battleships, Bombardments and the Black Sea

Drachinifel

Published 5 Apr 2023Today we take a look at most of the naval theaters of the Crimean War on conjunction with the fine people @realtimehistory find their video here: Last Crusade or F…

(more…)