toldinstone

Published 10 Sep 2022In this episode, Dr. Bret Devereaux (the blogger behind “A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry”) discusses the relationships between fantasy and ancient history – and why historical accuracy matters, even in fiction.

(more…)

September 12, 2022

The Lord of the Rings and Ancient Rome (with Bret Devereaux)

The art of the constitutional monarchy

At The Ruffian, Ian Leslie considers the form of government nobody set out to design, but has proven to be one of the most stable forms of government we’ve had:

The royal family at Buckingham Palace for the Trooping of the Colour, 30 June, 2015.

Photo by Robert Payne via Wikimedia Commons.

When I said that nobody would design this system, that is not a criticism. Evolved systems tend to work better than designed ones, even if they can seem maddeningly irrational to those who presume to know better. Yesterday somebody posted extracts from an essay by Clement Attlee. As a socialist, Attlee might have been expected to oppose or at least be sceptical of constitutional monarchy, but he was a strong believer in it. Attlee was writing in 1952, a year after the end of his term as Prime Minister, and the same year that Queen Elizabeth came to the throne. When he refers to the monarch, he refers to her – one of those examples of how the Queen’s longevity stretches our perception of time. “You will find the greatest enthusiasm for the monarch in the meanest streets,” he writes. After qualifying as a lawyer, Attlee ran a club in the East End of London for teenage boys raised in dire poverty. He remembers one of them saying, “Some people say as how the King and Queen are different from us. They aren’t. The only difference is that they can have a relish with their tea every day.”

Attlee notes that Norway, Sweden, and Denmark — countries in which there is “the highest equality of well-being” — have royal families. That’s still true and we might add the Netherlands to that list. While it’s impossible to disentangle the many historical factors that make for a decent and successful society, it is at the very least tough to make the case, on evidence alone, that democratic monarchies are inherently bad. Indeed, they seem to work pretty well versus other forms of government. As the left-wing American blogger Matt Yglesias remarked yesterday, “It’s hard to defend constitutional monarchy in terms of first principles, but the empirical track record seems good.”

If this is so, I’m interested in why (let’s agree, by the way, that there isn’t one definitively superior way of running a country, and that every system has flaws). My guess is that it’s because constitutional monarchies do a better job than more “rational” forms of government of accommodating the full spectrum of human nature. They speak to the heart as well as the head. Attlee puts it succinctly: “The monarchy attracts to itself the kind of sentimental loyalty which otherwise might to the leader of a faction. There is, therefore, far less danger under a constitutional monarchy of the people being carried away by a Hitler, a Mussolini or even a de Gaulle.” (I need hardly add that for Attlee, these were not merely historical figures.) Martin Amis, in the closing paragraph of his 2002 piece about the Queen for the New Yorker, expresses the same idea with characteristic flair:

“A princely marriage is the brilliant edition of a universal fact,” Bagehot wrote, “and as such, it rivets mankind.” The same could be said of a princely funeral — or, nowadays, of a princely divorce. The Royal Family is just a family, writ inordinately large. They are the glory, not the power; and it would clearly be far more grownup to do without them. But riveted mankind is hopelessly addicted to the irrational, with reliably disastrous results, planetwide. The monarchy allows us to take a holiday from reason; and on that holiday we do no harm.

Yes, there is something deeply sentimental and even loopy about placing a family at the centre of national life, and ritually celebrating them, not for what they’ve done but for who they are. But here’s the thing: humans are sentimental and yes, a bit loopy. Constitutional monarchies accept this, and separate the locus of sentiment from the locus of power. They divert our loopiness into a safe space.

In republics, the sentimentality doesn’t go away but becomes fused with politics, often to dangerous effect. Russia, despite having killed off its monarchy long ago, retains an ever more desperate hankering after grandeur, the consequences of which are now being suffered by the Ukrainians. America’s more “rational” system has given us President Donald Trump, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that their political culture is more viciously, irrationally polarised than ours.

Monarchy, in its democratic form, can also be a conduit for our better natures. It gives people a way to express their affection for the people with whom they share a country, by proxy. Think about that boy in Limehouse: it’s not that he wouldn’t have preferred to have relish with his tea – to be rich, or at least richer. But he recognised that, as different as human lives can be, they are always in some fundamental ways the same. People have mothers and fathers (present or absent, kind or cruel), brothers and sisters, hopes, fears, joys and anxieties. That’s why one family can stand in for all of us, even if that family lives in a very privileged and singular manner.

History Summarized: Classical Warfare (Feat. Shadiversity!)

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 22 Jul 2017How did people fight in ancient times? Well that’s a good question! Step right up and I’ll learn you a thing or two about history.

(more…)

September 11, 2022

“Learning is something we humans do, while schooling is something done to us”

Kerry McDonald refutes the “learning loss” narrative we’ve been inundated with:

“Abandoned Schoolhouse and Wheat Field 3443 B” by jim.choate59 is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

There are mounting concerns over profound learning loss due to prolonged school closures and remote learning. New data released last week by the US Department of Education reveal that fourth-grade reading and math scores dropped sharply over the past two years.

Fingers are waving regarding who is to blame, but the alleged “learning loss” now being exposed is more reflective of the nature of forced schooling rather than how children actually learn.

The current hullabaloo over pandemic learning loss mirrors the well-worn narrative regarding “summer slide”, in which children allegedly lose knowledge over summer vacation. In 2017, I wrote an article for Boston NPR stating that there’s no such thing as the summer slide.

Students may memorize and regurgitate information for a test or a teacher, but if it has no meaning for them, they quickly forget it. Come high school graduation, most of us forget most of what we supposedly learned in school.

In his New York Times opinion article this week, economist Bryan Caplan makes a related point: “I figure that most of the learning students lost in Zoom school is learning they would have lost by early adulthood even if schools had remained open. My claim is not that in the long run remote learning is almost as good as in-person learning. My claim is that in the long run in-person learning is almost as bad as remote learning.”

Learning and schooling are completely different. Learning is something we humans do, while schooling is something done to us. We need more learning and less schooling.

Yet, the solutions being proposed to deal with the identified learning loss over the past two years promise the opposite. Billions of dollars in federal COVID relief funds are being funneled into more schooling and school-like activities, including intensive tutoring, extended-day learning programs, longer school years, and more summer school. These efforts could raise test scores, as has been seen in Texas where students receive 30 hours of tutoring in each subject area in which they have failed a test, but do they really reflect true learning?

As we know from research on unschoolers and others who learn in self-directed education settings, non-coercive, interest-driven learning tends to be deep and authentic. When learning is individually-initiated and unforced, it is not a chore. It is absorbed and retained with enthusiasm because it is tied to personal passions and goals.

The Allies’ Latest Victory – WW2 – 211 – September 10, 1943

World War Two

Published 10 Sep 2022Dwight Eisenhower publicly announces the secret armistice signed last week, and Italy is now officially out of the war. The Italian fleet sails for Malta and Allied captivity. The Allies have landed in force in Southern Italy and they do face some heavy opposition from German forces — who have no intention of giving up Italy. In the USSR, though, the Soviets continue liberating territory all over Ukraine as they force the Germans back to the Dnieper River.

(more…)

Are we looking at a modern equivalent to the Bronze Age Collapse?

If you’re feeling happy and optimistic, Theophilus Chilton has a bucket of cold water to douse you with:

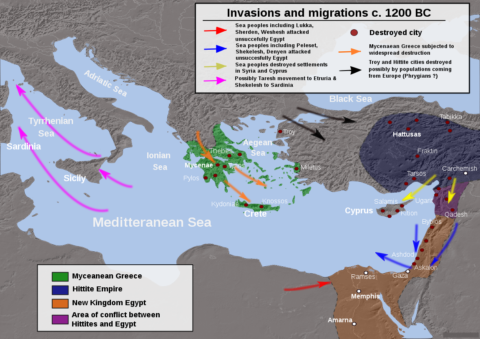

Migrations, invasions and destructions during the end of the Bronze Age (c. 1200 BC), based on public domain information from DEMIS Mapserver.

Map by Alexikoua via Wikimedia Commons.

Regular readers know that I’ve talked about collapse (as well as the implied regeneration that follows it) on here a lot. In nearly all cases, though, I’ve discussed it within a specifically American context – the collapse of the present American system and the potential for one or more post-American successor states arising in place of the present globohomo order. However, we should recognise that collapse is a general phenomenon that affects any and all large nations eventually. Just as America is not a special snowflake who is exempt from the laws of demographic-structural theory, so also is she not the only one subject to them.

Further in this vein, we should recognise that no major nation is isolated from its neighbours. No matter how self-sufficient, sooner or later everybody gets hooked up into trade networks. As trade networks expand, you develop world systems that display increased international interconnectedness and interdependency. From a demographic-structural perspective, the interconnectedness of these global systems acts to “synch up” the secular cycles of the nations involved as “information flows” increase. The upside to this is that when one part of the system prospers, everyone does. The downside, of course, is that when one part collapses, everyone does as well.

There are several historical examples of this kind of interconnected system synching up and then collapsing. Probably one of the most well-known examples would be the Bronze Age collapse which occurred in the Mediterranean world system roughly between 1225-1150 BC. Likely due to several shocks to the system working in tandem (drought, volcanic eruptions, migrations into the Balkans from the north, etc.), a series of invasions of the Sea Peoples spread out across the entire eastern end of the Mediterranean, toppling Mycenaean Greece and the Hittite Empire, and nearly did the same to Egypt. From there, the shocks moved outward throughout the rest of Anatolia and Syro-Palestine and eastward into Mesopotamia, disrupting the entire interconnected trade network. The system was apparently already primed to be toppled by these jolts, however, due to the top-heavy political structures (elite overproduction) and overspecialisation in these empires that contributed to their fragility in the face of system shocks. When the first one fell, the effects spread out like dominoes falling in a row.

There is evidence that this collapse extended beyond the Mediterranean basin and disrupted the civilisation existing in the Nordic Bronze Age around the Baltic Sea. Right around the same time that Bronze Age Mediterranean society was collapsing, serious changes to society in the Baltic basin were also taking place, primarily due to the disruption of trade routes that connected the two regions, with amber flowing south and metals and prestige goods returning north. During this period, the population in the area transitioned from a society organised primarily around scattered villages and farms into one that became more heavily militarised and centred around fortified towns, indicating that there was a change in the region’s elite organisation, or at least a strong modification of it (remember that collapse phases are characterised by struggles between competing elite groups). A large battle that dates to this era has been archaeologically uncovered in the Tollense Valley of northeastern Germany which is thought to have involved over 5000 combatants — a huge number for this area at this time, indicating more centralised state-like organisational capacities than were previously thought to have existed in the region. All in all, the evidence seems to suggest that this culture underwent some type of collapse phase at this time, likely in tandem with that occurring further south.

Other times and places have also seen such world system collapses take place. for instance, when the western Roman Empire was falling in the 3rd-5th centuries AD, the entire Mediterranean basis (again) underwent a systemwide socioeconomic collapse and decentralisation. More recently, the entire Eurasian trade system, from England to China, underwent a synchronised collapse phase in the early 17th century AD that saw revolutions, elite conflict, decentralisation, and social simplification take place across the length of the continent.

The great irony of interconnectedness is that too much of it actually works to reduce resilience within a system. Because an intensively globalised world system entails a lot of specialisation as different parts begin to focus on the production of different commodities needed within the network, this makes each part of the system more dependent upon the others. This works to reduce the resiliency of each of these individual parts, and the greater interconnectedness allows failure in one part to be communicated more widely and rapidly to other parts than might otherwise be the case in less interconnected systems.

MAS-36: The Backup Rifle is Called to Action

Forgotten Weapons

Published 25 Sep 2017There is a common assumption that the MAS-36 was a fool’s errand from the outset — why would a country develop a brand new bolt-action rifle in the mid 1930s, when obviously semiautomatic combat rifles were just on the cusp of widespread adoption? Well, the answer is a simple one — the French were developing a semiautomatic rifle at the same time, and the MAS-36 was only intended to go to rear echelon and reserve troops. It would serve as a measure of economy, reducing the number of the more complex and expensive self-loaders necessary, while still providing sufficient arms to equip the whole reserve in case of a mobilization.

Well, the plan didn’t quite work out that way, because Germany invaded France before the semiauto rifle was ready for production (it was, at that point, the MAS-40 and was in trials). Not until 1949 would the self-loader go into mass production with the MAS-49 (discounting the short-lived MAS-44). With this in mind, the MAS-36 suddenly makes much more sense. It is a simple, economical, and entirely adequate rifle without extraneous niceties. In a word, it is a Russian rifle rather than a Swiss one.

Production began in the fall of 1937, and by the time of the German invasion there were about 205,000 in French stockpiles. They saw extensive use in the Battle of France, along with M34 Berthiers in 7.5x54mm. Some would escape to serve the Free French forces worldwide through the war, and others would be captured and used by German garrisons in France and along the Atlantic Wall. Production resumed upon the liberation of St Etienne in 1944, and by 1957 about 1.1 million had been made. They basically fall into two varieties, with several pre-war milled components changed to more economical stamped designs after the war.

(more…)

QotD: De-institutionalization

[In Desperate Remedies: Psychiatry’s Turbulent Quest to Cure Mental Illness, Andrew] Scull stresses the degree to which external pressures have shaped psychiatry. “Community psychiatry” supplanted “institutional psychiatry” in part because of professional insecurity. Psychiatrists needed a new model for dealing with mental diseases to keep pace with the advances that mainstream health care was making with other diseases. Fiscal conservatives viewed the practice of confining hundreds of thousands of Americans to long-term commitment as overly expensive, and civil libertarians viewed it as unjust.

Deinstitutionalization began slowly at first, in the 1950s, but the pace accelerated around 1970, despite signs that all was not going according to plan. On the ground, psychiatrists noticed earlier than anyone else that the most obvious question — where are these people going to go when they leave the mental institutions? — had no clear answers. Whatever misgivings psychiatrists voiced over the system’s abandonment of the mentally ill to streets, slums, and jails was too little and too late.

That modern psychiatry is mostly practiced outside of mental institutions is not its only difference from premodern psychiatry. Scull devotes extensive coverage to two equally decisive developments: the rise and fall of Freudianism, and psychopharmacology.

The Freudians normalized therapy in America and provided crucial intellectual support for the idea that mental health care is for everyone, not just the deranged. Around the same time as deinstitutionalization, Freud’s reputation, especially in elite circles, was on a level with Newton and Copernicus. Since then, Freudianism has mostly gone the way of phlogiston and leeches. That happened not just because people decided the psychoanalysts’ approach to therapy didn’t work but also because insurance wouldn’t pay for it. Insurance would, however, pay for modes of therapy that were less open-ended than the “reconstruction of personality that psychoanalysis proclaimed as its mission”, more targeted to a specific psychological symptom, and, most crucially of all, performed by non-M.D.s. Therapy was on the rise, but psychiatrists found themselves doing less and less of it.

As psychiatry cast aside Freudian concepts such as the “refrigerator mother”, which rooted mental illness in psychodynamic tensions, it increasingly trained its focus on biology. Drugs contributed to, and gained a boost from, this reorientation. Scull loathes the drug industry and only grudgingly allows that it has made improvements in the lives of mentally ill Americans. He divides up the vast American drug-taking public into three groups: those for whom they work, those for whom they don’t work, and those for whom they may work, but not enough to counter the unpleasant side effects. He argues that the last two groups are insupportably large.

Stephen Eide, “Soul Doctors”, City Journal, 2022-05-18.

September 10, 2022

Magical Monetary Theory (MMT) – You’re soaking in it

At the Foundation for Economic Education, Kellen McGovern Jones outlines the rapid rise of MMT as “the answer to everyone’s problems” in the last few years and all the predictable problems it has sown in its wake:

“Inflation & Gold” by Paolo Camera is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) was the “Mumble Rap” of politics and economics in the late 2010s. The theory was incoherent, unsubstantial, and — before the pandemic, you could not avoid it if you wanted to.

People across the country celebrated MMT. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the Democrat Congresswoman from New York heralded MMT by proclaiming it “absolutely [must be] … a larger part of our conversation [on government spending].” The New York Times and other old-guard news sources authored countless articles raising the profile of MMT, while universities scrambled to hold guest lectures with prominent MMT economists like Dr. L. Randall Wray. Senator Bernie Sanders went as far as to hire MMT economists to his economic advisory team.

The most fundamental principle of MMT is that our government does not have to watch its wallet like everyday Joes. MMT contends that the government can spend as much as it wants on various projects because it can always print more money to pay for its agenda.

Soon after MMT became fashionable in the media, the once dissident economic theory leapt from being the obscure fascination of tweedy professors smoking pipes in universities to the seemingly deliberate policy of the United States government. When the Pandemic Hit, many argued that MMT was the solution to the pandemics problems. Books like The Deficit Myth by Dr. Stephanie Kelton became New York Times bestsellers, and the United States embarked on a massive spending spree without raising taxes or interest rates.

Attempting to stop the spread of Covid, state and federal governments coordinated to shut down nearly every business in the United States. Then, following the model of MMT, the federal government decided to spend, and spend, and spend, to combat the shutdown it had just imposed. Both Republican and Democrat-controlled administrations and congresses enacted trillions of dollars in Covid spending.

It is not hard to see that this spray and pray mentality of shooting bundles of cash into the economy and hoping it does not have any negative consequences was ripe for massive inflation from the beginning. Despite what MMT proponents may want you to believe, there is no way to abolish the laws of supply and demand. When there is a lot of something, it is less valuable. Massively increasing the supply of money in the economy will decrease the value of said money.

MMT economists seemed woefully unaware of this reality prior to the pandemic. Lecturing at Stoney Brook University, Kelton attempted to soothe worries about inflation by explaining that (in the modern economy) the government simply instructs banks to increase the number of dollars in someone’s bank account rather than physically printing the US Dollar and putting it into circulation. Somehow — through means that were never entirely clear — this fact was supposed to make people feel better.

In reality, there is no difference between changing the number in someone’s bank account or printing money. In both cases, the result is the same, the supply of money has increased. Evidence of MMTs inflationary effects are now everywhere.

“Things have gone horribly wrong in American medicine; for example, ‘physicians are sharing ideas'”

Chris Bray on the American healthcare system’s descent into not just “rule by experts” — which you rather expect for a field like medicine — but the far worse “rule by government-approved experts”:

Our $3.7 trillion medical system is characterized by its fragility, the narrative says, with patients who can’t get treatment and doctors who can’t learn. So what’s gone wrong? Here’s the headline, with a whole universe of silly assumptions baked into every word:

Things have gone horribly wrong in American medicine; for example, “physicians are sharing ideas”.

I’m just taking a moment to stare at my own sentence. Be right back.

Anyway, medicine is broken — doctors are thinking. Sick people show up to see them, and they try to figure it out themselves by using, like, evidence and diagnostic practice and their medical knowledge. Lacking government directives, physicians are living with a horrible system in which they have to assess sick people and come up with their own answers about their illnesses and the best course of treatment. And so, Politico reports, networks of doctors are gathering to share data and work collaboratively, a sure sign that things have gone horribly wrong:

While the network is helping patients and doctors navigate the disease’s uncharted waters, long Covid doctors say there’s only so much they can do on their own. The federal government should be doing more, they say, to provide resources, coordinate information sharing and put out best practices. Without that, the doctors involved fear the condition, which has kept many of those afflicted out of the workforce, threatens to spiral.

Imagine what doctors will be like after two more generations shaped by the assumption that the federal government is the only proper source of “best practices”. The pathologization of socially and institutionally healthy behavior — professionals, confronted with a new problem, work together to gather evidence so they can analyze and apply it — speaks to the ruin inflicted by the pandemic, by the federal funding and steering of science, and by the Saint Anthonying of medicine: If government doesn’t tell you how, you can’t possibly know how. You expect your doctor to use a lifetime of education and experience to figure out what’s wrong with you; Politico expects your doctor to apply the government guidelines, but finds to its alarm that the government doesn’t offer any. How can you make a sandwich if the government hasn’t published a protocol on the application of condiments?

If you’ve felt rigidity and a lack of productive exchange in your conversations with your own doctor, we may have a suggestion here about the why part. I can’t assert that with total confidence, because the federal government hasn’t provided me with an analytical framework.

And so the debilitation of people who should have professional knowledge and competence becomes normal and expected. A scientist is someone who gets checks from the NIH, unless the scientist is one of the other kind and gets checks from the NSF, and ideological compliance is part of the deal. A doctor is someone who applies the government protocols. Federal agencies wear your doctors like a skin suit, and apply their medical solutions through the hands of others. If that’s not how it works — if your doctor works in creative and thoughtful ways to make sense of an illness and provide an effective treatment — something has gone wrong.

The Land Rover Defender Story

Big Car

Published 27 Dec 2019The Land Rover is Britain’s bullet-proof off-roader born out of Rover’s post-war desperation and became the indispensable go-anywhere vehicle. Like its famed bullet-proof ruggedness, Land Rover production kept going, and going, and going. But with a brief gap of 4 years, the Land Rover is still with us and looks like it’s not going away any time soon.

(more…)

QotD: “Working toward the Führer“

Sir Ian Kershaw was broadly right about how the Third Reich operated. He says Nazi functionaries were “working towards the Führer“. In other words, the Führer — the idealized, mythologized leader, not Adolf Hitler the individual — made it known that “National Socialism stands for X“. Hitler was famously averse to giving direct orders, so that’s often the only thing big, important parts of the government had to work from — the Führer‘s* pronouncement that “National Socialism means X“. It was up to them to put it into practice as best they could.

This had several big advantages. First, it’s in line with Nazi philosophy. The Nazis were Social Darwinists. Social Darwinists hold that “survival of the fittest” applies not only to humans as a whole, but to human social groups as well. Any given organization, then, must exist to do something, to advance some cause, to reach some goal. Ruthless competition between groups, and inside each group, is how the goal works itself out (you should be hearing echoes of Hegel here). The struggle refines and clarifies what the group’s goal is, even as the individual group members compete to reach it. The end result gets forced back up the system to the Führer, such that, dialectically (again, Hegel), “National Socialism means X” now encompasses the result of the previous struggle.

[…]

As with philosophy, “working towards the Führer” fit well with German military culture. Auftragstaktik is a fun word that means “mission-type tactics.” In practice, it delegates authority to the lowest possible level. Each subordinate commander is given an objective, a force, and a due date. High command doesn’t care how the objective gets taken; it only cares that the objective gets taken. Done right, it’s a wonderfully efficient system. It’s the reason the Wehrmacht could keep fighting for so long, and so well, despite being overpowered in every conceivable way by the Allies. The Allies, too, were constantly flabbergasted by their opponents’ low rank — corporals and sergeants in the Wehrmacht were doing the work of an entire Allied company command staff (and often doing it better).

Consider the career of Adolf Eichmann. In the deepest, darkest part of the war, this man pretty much ran the Reich’s rail network. Say what you will about the Nazi’s plate-of-spaghetti org chart, that’s some serious power. He was a lieutenant colonel.

The final great advantage of “working towards the Führer” is “plausible deniability”. Let’s stipulate Atrocity X. Let’s further stipulate that we’re in the professional historian’s fantasy world, where every conceivable document exists, and they’re all clear and unambiguous. It’s a piece of cake to pin Atrocity X on someone … and that someone would, in all probability, be a corporal or a sergeant. Maybe a lieutenant. What you wouldn’t be able to do is trace it up the chain any higher. Everyone from the captain to Hitler himself could / would give you the “Who, me?” routine. “I didn’t tell Sergeant Schultz to execute those prisoners. All I said was to go secure that objective / defeat that army / that National Socialism means fighting with an iron will.”

*I’m deliberately conflating them here — to make it clearer how confusing this could be — but in talking about this stuff the terminology is crucial. Adolf Hitler, the man, played the role of The Führer. What Hitler the man wanted was often in line with what the Führer role required, of course, but not always. This is one of the footholds Holocaust deniers have. Did Hitler-the-man actually put his name to a liquidation order? No. Did Hitler-the-man actually want it to happen? Unquestionably yes, but like all men, Hitler-the-man vacillated, had second thoughts, doubted himself, etc., and you can find documented instances of that. But The Führer very obviously wanted it to happen, and it was The Führer that motivated the rank-and-file. The man created the role, but very soon the role started playing the man …

Severian, “Working Towards the Deep State”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-01-06.

September 9, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 2 – Survival and Growth

seangabb

Published 15 Oct 2021Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)