Jill Bearup

Published May 13, 2024Ah, Captain Blood. Swords, sand, and piratical shenanigans. Let’s do this.

The Fight Master Vol 1 Issue 1: https://mds.marshall.edu/fight/1/

Buy my book: books2read.com/juststabmenow (or try your local Amazon/bookstore)

August 28, 2024

Then I’ll Take Her When You’re  Dead

Dead !

!

Dead

Dead !

! August 25, 2024

QotD: P.G. Wodehouse’s unique way to get letters delivered

In previous columns […] I wrote about Homage to PG Wodehouse, a 1973 tribute edited by Thelma Cazalet-Keir, sister-in-law of Wodehouse’s beloved stepdaughter Leonora. My final extracts begin with an account by the American Guy Bolton (1884-1979), who collaborated with the Master on no fewer than 21 musical comedies for the stage and became his lifelong friend. In one of my favourite anecdotes, he describes how he called on Wodehouse in London in the mid-1920s.

“He was living in bachelor quarters in a tall, old-fashioned building in Queen’s Gate. His flat was on the fifth floor. There was no lift. I was travel tired and I toiled up the long staircase, pausing on the landings to pant. I found his door ajar and, entering, I found him writing a letter. He greeted me with a cheery ‘Hurrah, you’re here!’ and added, ‘Just a tick and I’ll get this letter off.’

“He shoved the letter in an envelope, stuck a stamp on it, then went over to the half-open window and tossed it out. ‘What on earth?’ I asked. ‘Has the joy of seeing me brought on some sort of mental lapse? That was your letter you just threw out of the window.’ ‘I know that. I can’t be bothered to go toiling down five flights every time I write a letter.’ ‘You depend on someone picking it up and posting it for you?’ ‘Isn’t that what you would do if you found a letter stamped and addressed lying on the pavement? All I can say is it works.’ ‘Well I wish you’d write me a letter while I’m here in London. I’d like to show it round in America – a bit of a score for good old England’.”

Bolton goes on: “It was the second day after moving into a fourth-floor flat in South Audley Street when my doorbell rang and I opened it to a rather stout individual somewhat out of breath. ‘Are you Mr Bolton? I have a letter for you.’ The envelope was in Plum’s handwriting.

“He said he was a taxi driver but refused a tip, accepting instead a bottle of Guinness. While he was drinking it, I phoned Plum. ‘I have your letter,’ I said. ‘What?’ said Plum in a slightly awed voice. ‘I only threw it out of the window 20 minutes ago.’ ‘You were right,’ I said. ‘It’s by far the quickest way to send a letter to a friend in London.’ ‘Yes, indeed. The GPO had better look to their laurels and keep an eye on their laburnums’.”

Of his friend, Bolton says: “He has one quality that is rare in our age. It is innocence. It carries with it a trusting belief in the goodness of heart of his fellow men. Suspicion and distrust have no place in his nature. The characters in his books share in it – even his villains are likely to succumb before a finger shaken by one of those bright-eyed, no-nonsense Wodehouse heroines.”

Alan Ashworth, “That reminds me: A final homage to Wodehouse”, The Conservative Woman, 2024-05-21.

August 12, 2024

Robin Hood, But Make it  ICONIC

ICONIC

Jill Bearup

Published Apr 29, 2024The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) is a classic, and I am hopefully unlikely to get in copyright trouble if I use huge chunks of it. So prepare for an exhaustive (or possibly exhausting) fight breakdown, and a few minor comments about Errol Flynn and parrying.

(more…)

ICONIC

ICONIC

August 3, 2024

The Rise, Fall, And Revival Of Art Deco | A Style Is Born W/ @KazRowe

Wayfair

Published Jun 15, 2023Welcome to A Style is Born, hosted by YouTuber, cartoonist, and champion of under-represented history, Kaz Rowe!

Join us as we go down the rabbit hole and uncover the unique histories and origin stories behind your favorite design styles. In this first episode of Season 2, we delve into the history-rich Art Deco movement.

Chapters

Intro – 00:00

History – 00:45

Influences, Elements, & Materials – 04:58

1980s Art Deco Revival Via Memphis Group – 07:46

Conclusion – 09:13

(more…)

July 28, 2024

How America RUINED the world’s screws! (Robertson vs. Phillips)

Stumpy Nubs

Published Apr 17, 2024

July 27, 2024

Dining on the Orient Express

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Apr 16, 2024Côtelettes d’Agneau à la Minute

Simple, delicious fried lamb cutlets with a lemon-butter sauce with swirls of Duchess PotatoesCity/Region: France

Time Period: 1903The food and dining cars of the Orient Express were a big part of the luxurious experience that drew in passengers. The chefs, who were brought in from top French institutions, prepared meals on moving train cars, sometimes themed to which countries the train was passing through.

These lamb cutlets are simple, tender, and delicious. The lemon-butter sauce has only two ingredients, and pairs perfectly with Duchess Potatoes for a wonderful meal (or more accurately, single course) aboard the Orient Express.

Côtelettes d’Agneau à la Minute

Cut the cutlets very thin, season them and shallow fry in very hot clarified butter. Arrange them in a circle on a dish, sprinkle with a little lemon juice and the cooking butter after adding a pinch of chopped parsley, Serve immediately.

— Le Guide Culinaire by Auguste Escoffier, 1903

June 10, 2024

Bigger Isn’t Always Better: A1E1 Independent | Tank Chats Reloaded

The Tank Museum

Published Mar 1, 2024A bigger tank is a better tank, right? Wrong.

Meet the Interwar Vickers A1E1 Independent: a failed prototype, a prototype that proved bigger isn’t always better. Impractical and expensive, it was never accepted into service – but it is said to have inspired equally cumbersome designs including the German Neubaufahrzeug and the Soviet T-35.

Join David Willey, The Tank Museum Curator, as he examines one of the more unusual vehicles in the collection – and discover how it became a focus for political espionage in the early 1930’s.

00:00 | Introduction

02:56 | Tank Design & Vickers

03:28 | Heavy Tank Requirements

05:38 | Initial Blueprints & Prototypes

11:08 | Test-bed Vehicle

14:50 | Myths, Issues and Life after Trials

19:25 | Does it lead to anything?This video features archive footage courtesy of British Pathé.

#tankmuseum #davidwilley #Interwar #heavytanks

May 18, 2024

The plight of Greek refugees after the Greco-Turkish War

As part of a larger look at population transfers in the Middle East, Ed West briefly explains the tragic situation after the Turkish defeat of the Greek invasion into the former Ottoman homeland in Anatolia:

“Greek dialects of Asia Minor prior to the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Evolution of Greek dialects from the late Byzantine Empire through to the early 20th century leading to Demotic in yellow, Pontic in orange, and Cappadocian in green. Green dots indicate Cappadocian Greek speaking villages in 1910.”

Map created by Ivanchay via Wikimedia Commons.

While I understand why people are upset by the Nakba, and by the conditions of Palestinians since 1948, or particular Israeli acts of violence, I find it harder to understand why people frame it as one of colonial settlement. The counter is not so much that Palestine was 2,000 years ago the historic Jewish homeland – which is, to put it mildly, a weak argument – but that the exodus of Arabs from the Holy Land was matched by a similar number of Jews from neighbouring Arab countries. This completely ignored aspect of the story complicates things in a way in which some westerners, well-trained in particular schools of thought, find almost incomprehensible.

The 20th century was a period of mass exodus, most of it non-voluntary. Across the former Austro-Hungarian, Russian and Ottoman empires the growth in national consciousness and the demands for self-determination resulted in enormous and traumatic population transfers, which in Europe reached its climax at the end of the Second World War.

Although the bulk of this was directed at Germans, the aggressors in the conflict, they were not the only victims – huge numbers of Poles were forcibly moved out of the east of the country to be resettled in what had previously been Germany. The entire Polish community in Lwów, as they called it, was moved to Wrocław, formerly Breslau.

Maps of central and eastern Europe in the 19th century would have shown a confusing array of villages speaking a variety of languages and following different religions, many of whom wouldn’t have been aware of themselves as Poles, Romanians, Serbs or whatever. These communities had uneasily co-existed under imperial rulers until the spread of newspapers and telegraph poles began to form a new national consciousness, usually driven by urban intellectuals LARPing in peasant fantasies.

This lack of national consciousness was especially true of the people who came to be known as Turks; the Balkans in the late 19th century had a huge Muslim population, most of whom were subsequently driven out by nationalists of various kinds. Many not only did not see themselves as Turks but didn’t even speak Turkish; their ancestors had simply been Greeks or Bulgarians who had adopted the religion of the ruling power, as many people do. Crete had been one-third Muslim before they were pushed out by Greek nationalists and came to settle in the Ottoman Empire, which is why there is still today a Greek-speaking Muslim town in Syria.

This population transfer went both ways, and when that long-simmering hatred reached its climax after the First World War, the Greeks came off much worse. Half a million “Turks” moved east, but one million Greek speakers were forced to settle in Greece, causing a huge humanitarian crisis at the time, with many dying of disease or hunger.

That population transfer was skewed simply because Atatürk’s army won the Greco-Turkish War, and Britain was too tired to help its traditional allies and have another crack at Johnny Turk, who – as it turned out at Gallipoli – were pretty good at fighting.

The Greeks who settled in their new country were quite distinctive to those already living there. The Pontic Greeks of eastern Anatolia, who had inhabited the region since the early first millennium BC, had a distinct culture and dialect, as did the Cappadocian Greeks. Anthropologically, one might even have seen them as distinctive ethnic groups altogether, yet they had no choice but to resettle in their new homeland and lose their identity and traditions. The largest number settled in Macedonia, where they formed a slight majority of that region, with many also moving to Athens.

The loss of their ancient homelands was a bitter blow to the Greek psyche, perhaps none more so than the permanent loss of the Queen of Cities itself, Constantinople. This great metropolis, despite four and a half centuries of Ottoman rule, still had a Greek majority until the start of the 20th century but would become ethnically cleansed in the decades following, the last exodus occurring in the 1950s with the Istanbul pogroms. Once a mightily cosmopolitan city, Istanbul today is one of the least diverse major centres in Europe, part of a pattern of growing homogeneity that has been repeated across the Middle East.

But the Greek experience is not unique. Imperial Constantinople was also home to a large Jewish community, many of whom had arrived in the Ottoman Empire following persecution in Spain and other western countries. Many spoke Ladino, or Judeo-Spanish, a Latinate language native to Iberia. Like the Greeks and Armenians, the Jews prospered under the Ottomans and became what Amy Chua called a “market-dominant minority”, the groups who often flourish within empires but who become most vulnerable with the rise of nationalism.

And with the growing Turkish national consciousness and the creation of a Turkish republic from 1923, things got worse for them. Turkish nationalists and their allies murdered vast numbers of Armenians, Greeks and Assyrian Christians in the 1910s, and the atmosphere for Jews became increasingly tense too, with more frequent outbursts of communal violence. After the First World War, many began emigrating to Palestine, now under British control and similarly spiralling towards violence caused by demographic instability.

May 3, 2024

Art Deco vs Streamline Moderne

Michael Pacitti

Published Dec 24, 2022Differentiating between Art Deco and Streamline Moderne can be difficult if you don’t know their history. They are two very different periods of design. Here is a look at those differences, characteristics, colors, transportation, influences, and more.

April 28, 2024

How Britain got out of the Great Depression (and no, it wasn’t WW2)

Tim Worstall, in refuting something being pushed by Willie Hutton, explains how the British government escaped from the Great Depression and set off a nice little boom in the mid- to late-1930s:

Well, yes. Except that’s not actually what did drag Britain out of the Depression. What did was expansionary fiscal austerity. You know, that thing the Tories talked of in 2010 and which everyone laughed at? Somewhat annoyingly I was one of the very few (it’s annoying because I was clearly right in what I was saying) who pointed this out back then.

When we boil this right down it’s an argument about the effectiveness of monetary policy. Absolutely no one thinks that it has no effect. But there’s many who think that it has no effect at the zero lower bound: when interest rates are zero. That’s really the argument that leads to fiscal policy, that idea that government might tax less, or spend more, blow out that deficit and get the economy moving again. We’ve done all we could with monetary policy and we’ve still got to do something so here’s fiscal policy.

To put it as simply as possible. We’ve two major macroeconomic tools, monetary policy and fiscal. The first is interest rates, exchange rates and money printing and so on. The second is the difference between taxes collected and money spent by government — the government deficit or surplus (note, please, for purists, this is being very simple).

OK, either lever or tool can be used to loosen conditions — gee stuff up — or tighten them. Which we use when is somewhere between a matter of taste and necessarily correct given the circumstances. But clearly the total amount of geeing up out of a recession — or tightening to prevent inflation — or depression is the combination of the two sets of policies, applications of levers and tools.

It’s thus theoretically possible to tighten with one, loosen with the other and gain, overall, either tightening or loosening. Depends upon how much of each you do.

Britain in the 30s tightened fiscal policy. The opposite of what the Keynesians said, the opposite of what the US did and so on. Cut — no, really cut, not just slowed the increase in — government spending and thereby cut the government deficit (might, actually, have gone into surplus, not sure). This is, according to the Keynesian line, something that should make the recession/depression worse.

But at the same time they came off the gold standard — Churchill had taken us back in in 1925 at far too high a rate — and lowered interest rates. That’s a loosening of monetary policy.

As it happens, on balance, the monetary was loosened more than the fiscal was tightened and so we have expansionary fiscal austerity. Which set off a very nice little boom in fact. The mid- to late- 30s in Britain were economic good times. Driven, nicely driven, by a housebuilding boom — the last time the private sector built 300 k houses a year in fact (this is before the Town and Country Planning Act stopped all that). Mixed in was that the motor car was becoming a fairly standard bourgeois item and so housing spread out along the roads.

April 27, 2024

Floating Fun: The History of the Amphibious Boat Car

Ed’s Auto Reviews

Published Aug 9, 2023A classic car connoisseur dives into the general history of amphibious cars and vehicles. When did people start to build boat-car crossovers? What made Hans Trippel’s Amphicar 770 and the Gibbs Aquada so special? And why don’t you see a lot of amphibious automobiles out on the road and water these days?

(more…)

April 22, 2024

Did Japan Attack Pearl Harbor Because Of China?

Real Time History

Published Dec 1, 2023December 7, 1941: The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor shocked the world and brought the US into the Second World War. But why did the Japanese resort to such an attack against a powerful rival and what did it have to do with the Japanese war in China?

(more…)

April 16, 2024

Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Impresa – the 1919 occupation of Fiume

Ned Donovan on the turbulent history of the Adriatic port of Fiume (today the Croatian city of Rijeka) after the end of the First World War:

Fiume was a port on the Adriatic coast with several thousand residents, almost half of whom were ethnic Italians that had been under Austro-Hungarian rule for several hundred years after it once having been a Venetian trade port. By some quirk, Fiume was missed in the Treaty of London, probably because it had never been envisioned by the Allies that the Austro-Hungarian Empire would ever truly disintegrate and the rump of it that would remain required a sea port in some form. The city’s other residents were ethnically Serbian and Croatian, who knew the city as Rijeka (as you will find it named on a map today). All of this complexity meant that the fate of Fiume became a major topic of controversy during the Versailles Peace Conference. President Woodrow Wilson had become so unsure of what to do that he proposed the place become a free city and the headquarters of the nascent League of Nations, under the jurisdiction of no country.

By September 1919 there was still no conclusion as to the fate of Fiume. Events had overtaken the place and through the Treaty of St Germain, the Austro-Hungarian Empire had been dissolved after the abdication of the final Habsburg Emperor Charles I. Once again, Fiume had not been mentioned in the treaty and the country it had been set aside for no longer existed. The city’s fate was still at play.

Enter Gabriele D’Annunzio, an aristocrat from Abruzzo on the eastern coast of Italy. Born in 1863, he was a handsome and intelligent child and was nurtured by his family to be exceptional, with a predictable side effect of immense selfishness. As a teenager, he had begun to dabble in poetry and it was praised by authors unaware of his age. At university he began to be associated with Italian irredentism, a philosophy that yearned for all ethnic Italians to live in one country – by retaking places under foreign rule like Corsica, Malta, Dalmatia and even Nice.

[…]

The Italian government’s lack of interest [in Fiume] was unacceptable to D’Annunzio and he made clear he would take action to prevent it becoming part of Yugoslavia by default. With his fame and pedigree he was able to quickly assemble a small private force of ex-soldiers, who he quickly took to calling his “legionaries”. In September 1919 after the Treaty of St Germain was signed, his small legion of a few hundred marched from near Venice to Fiume in what they called the Impresa – the Enterprise. By the time he had reached Fiume, the “army” numbered in the thousands, the vanguard crying “Fiume or Death” with D’Annunzio at its head in a red Fiat.

The only thing that stood in his way was the garrison of the Entente, soldiers who had been given orders to prevent D’Annunzio’s invasion by any means necessary. But amongst the garrison’s leaders were many [Italian officers] sympathetic to D’Annunzio’s vision, some even artists themselves and before long most of the defenders had deserted to join the poet’s army. On the 12th September 1919, Gabriele D’Annunzio proclaimed that he had annexed Fiume to the Kingdom of Italy as the “Regency of Carnaro” – of which he was the Regent. The Italian government was thoroughly unimpressed and refused to recognise their newest purported land, demanding the plotters give up. Instead, D’Annunzio took matters into his own hands and set up a government and designed a flag (to the right).

The citizens of what had been a relatively unimportant port quickly found themselves in the midst of one of the 20th Century’s strangest experiments. D’Annunzio instituted a constitution that combined cutting-edge philosophical ideas of the time with a curious government structure that saw the country divided into nine corporations to represent key planks of industry like seafarers, lawyers, civil servants, and farmers. There was a 10th corporation that existed only symbolically and represented who D’Annunzio called the “Supermen” and was reserved largely for him and his fellow poets.

These corporations selected members for a state council, which was joined by “The Council of the Best” and made up of local councillors elected under universal suffrage. Together these institutions were instructed to carry out a radical agenda that sought an ideal society of industry and creativity. From all over the world, famous intellectuals and oddities migrated to Fiume. One of D’Annunzio’s closest advisers was the Italian pilot Guido Keller, who was named the new country’s first “Secretary of Action” – the first action he took was to institute nationwide yoga classes which he sometimes led in the nude and encouraged all to join. When not teaching yoga, Keller would often sleep in a tree in Fiume with his semi-tame pet eagle and at least one romantic partner.

If citizens weren’t interested in yoga, they could take up karate taught by the Japanese poet Harukichi Shimoi, who had translated Dante’s works into Japanese. Shimoi, who quickly became known to the government of Fiume as “Comrade Samurai” was a keen believer in Fiume’s vision and saw it as the closest the modern world had come to putting into practice the old Japanese art of Bushido.

The whole thing would have felt like a fever dream to an outsider. If a tourist was to visit the city, they would have found foreign spies from across the world checking into hotels and rubbing shoulders with members of the Irish republican movement while others did copious amounts of cocaine, another national pastime in Fiume. The most fashionable residents of Fiume carried little gold containers of the powder, and D’Annunzio himself was said to have a voracious habit for it. Sex was everywhere one turned and the city had seen a huge inward migration of prostitutes and pimps within days of D’Annunzio’s arrival. Almost every day was a festival, and it was an odd evening if the harbour of Fiume did not see dozens of fireworks burst above it, watched on by D’Annunzio’s uniformed paramilitaries.

D’Annunzio himself lived in a palace overlooking the city, Osbert Sitwell describes walking up a steep hill to a Renaissance-style square palazzo which inside was filled with plaster flowerpots the poet had installed and planted with palms and cacti. D’Annunzio would cloister himself in his rooms for 18 hours a day and without food. Immaculate guards hid amongst the shrubs to ensure he would not be disturbed. In D’Annunzio’s study, facing the sea, he sat with statutes of saints and with French windows onto the state balcony. When he wanted to interact with his people he would wait for a crowd to form over some issue, walk to the balcony and then ask what they wanted.

April 15, 2024

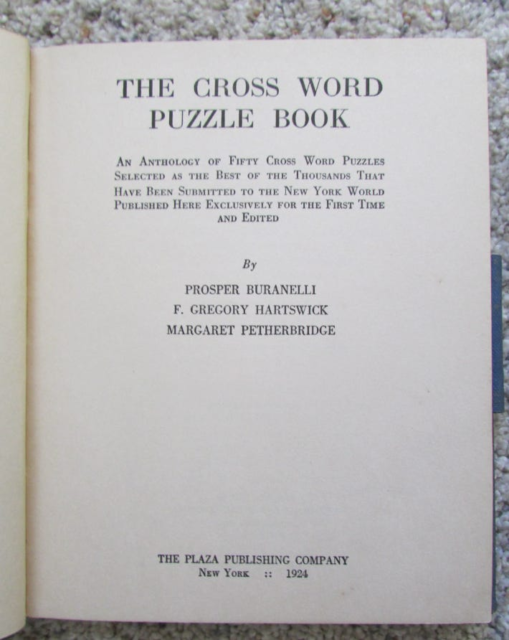

Simon & Schuster, founded 1924

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte provides a thumbnail history of the American publishing house Simon & Schuster:

The firm was started by Richard Leo Simon, a Great War veteran and piano salesman, and his partner, Max Lincoln Schuster, an auto magazine editor. They had met when Simon failed to sell Schuster a piano. They scraped together $8,000 in savings and loans from friends, family, and a telephone operator, and launched their first title in 1924: The Cross Word Puzzle Book, a collection compiled by the editors of the New York World, which was reputed to have the best crossword of the day. Each copy of the book came with a pencil and an eraser.

Messrs. Simon and Schuster initially called themselves The Plaza Publishing Company (something S&S doesn’t mention on its history webpage). They didn’t want to be personally associated with a novelty publishing project.

The novelty project sold 40,000 copies in three months and just under half a million in its first year, earning the boys a profit of $100,000, which has to be the fastest start ever for a book publisher. The Cross Word Puzzle Book was a cash cow for decades to come — there were at least fifty-six more editions, the vast majority published as S&S books. Its proceeds funded many better quality publishing initiatives.

Will Durant’s The Story of Philosophy was published in 1926 to critical success and impressive sales. Hervey Allen’s Anthony Adverse won the Pulitzer in 1934, as did Thomas Wolfe’s You Can’t Go Home Again in 1940. Will and Ariel Durant’s eleven-volume The Story of Civilization, which started publishing in 1935 and would take forty years to complete, also won a Pulitzer and was another huge seller.

By the time S&S acquired the paperback rights to Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind in 1942 and Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby in 1945, it was already the leading publisher in America. To make sure everyone knew it, the boys moved into a stunning new headquarters at one of the most expensive addresses in the world, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, part of Rockefeller Center.

While it was winning its share of literary awards and publishing some great books, Simon & Schuster never forgot its roots in commercial projects. In mid-life it was famous as the how-to publisher: How to Read a Book, How to Improve your Memory, How to Raise a Dog, How to Think Straight, How to Play Winning Checkers, and the bestselling granddaddy of them all, Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People, which has sold a staggering thirty million copies and still routinely shows up on bestseller lists.

Interestingly, the operational brains behind S&S was an unnamed partner, Leonard Shimkin, who joined the company as business manager at age seventeen. It was largely at Shimkin’s initiative that S&S launched Pocket Books in 1939, establishing the concept of inexpensive paperbacks, which broadened the reading public and opened the door to the expansion of genre fiction. He was also the one who walked Dale Carnegie into S&S.

The boys sold the company to Marshall Field, owner of the Chicago Sun, in 1944 but continued to work at it. They bought it back when Field died in 1956, this time with Shimkin taking an equity position. Simon retired in 1957 and Schuster not long after, eventually leaving Shimkin with sole ownership.

Meanwhile, the hits kept coming. Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 in 1961, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962, Capote’s In Cold Blood in 1966, Alex Haley’s Roots in 1976, Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove in 1985, Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time in 1988, and so on.

In 1975, Shimkin sold S&S to Gulf + Western, the first in a depressing series of corporate foster homes, none of which has known anything about or cared anything for books. G+W became Paramount in 1989, which was acquired by Viacom in 1994, which split into two companies in 2005, with Simon & Schuster becoming part of CBS Corporation, which in 2019 was merged back with Viacom, which in 2022 changed its name to Paramount Global and, after failing to unload S&S to Penguin Random House that same year, landed it with KKR the next. More on why all the corporate shuffling is far from over here.

Simon & Schuster and its subsidiary, Scribner, are the last great American-owned monuments to the golden age of American book publishing, which runs from about 1920 through to … I don’t know, the 1970s? All the others — Random House, Knopf, HarperCollins, Little, Brown & Co. — are owned by foreign conglomerates (HC’s owner, News Corp, is technically American but its controlling family, the Murdochs, are culturally British when they’re not being Australian).

April 14, 2024

Elmer Keith’s Revolver Number 5

Forgotten Weapons

Published Feb 28, 2015Elmer Keith’s No.5 Single Action Army is arguably the most famous custom revolver ever made. Keith had it built in 1928 after developing a friendship with Harold Croft, another revolver enthusiast. Croft had shown Keith his own custom revolvers, which he had numbered 1 through 4. Croft had been trying to make an ideal pocket gun, and Keith used several of his ideas along with some of Keith’s own to put together a revolver for general-purpose field use. In recognition of Croft’s work, Keith called his gun Number 5. It featured an extended flat top with windage-adjustable sights, an improved mainspring, redesigned cylinder pin, custom hammer spur, and modified Bisley grip. It was chambered for the .44 Special/.44 Russian cartridges (the Russian being a slightly shorter version of the Special), and it was Keith’s favorite shooting piece until the .44 Magnum cartridge was introduced in the late 1950s. He described this gun in detail in a 1929 American Rifleman article entitled “The Last Word”.

http://www.forgottenweapons.com

Theme music by Dylan Benson – http://dbproductioncompany.webs.com