In The Line, James McLeod outlines a difficult period for the Dominion of Newfoundland which ended up narrowly voting to join Canada rather than resume self-rule that they’d had up to 1934 when the Newfoundland House of Assembly abolished itself:

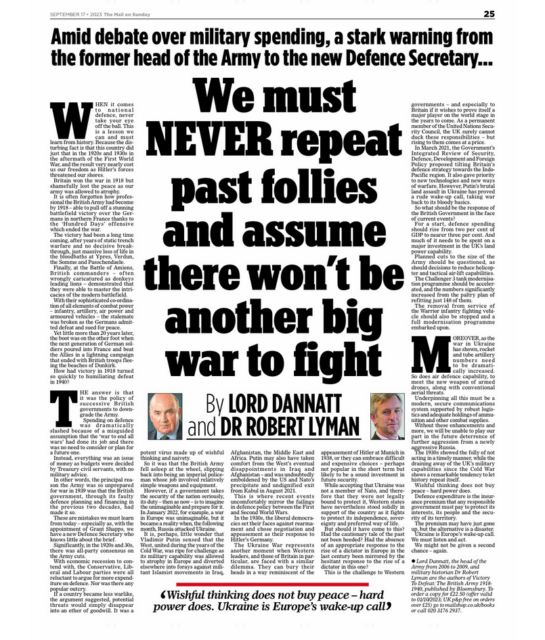

Great Riot of 1932 in front of the legislature, the Colonial Building, in Newfoundland.

Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador (Reference PANL A2-160), via Wikimedia Commons.

Before 1933, Newfoundland was proudly a dominion within the British empire. Under the Statute of Westminster, Newfoundland had the same legal status as Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and the Irish Free State.

Newfoundland was its own country. But it was a country in rough shape.

A year before the Amulree Report was published, a mob of about 10,000 people had gathered outside the Colonial Building in St. John’s. Families were living in destitution on six-cents-a-day government dole, and the government’s finance minister had just resigned and accused Prime Minister Richard Squires of personally lining his pockets with government funds.

The mob turned into a riot, which ultimately barged into the government building. Notably, the rioters briefly paused to observe a respectful silence when a brass band began playing “God Save The King”, but then they went back to rioting.

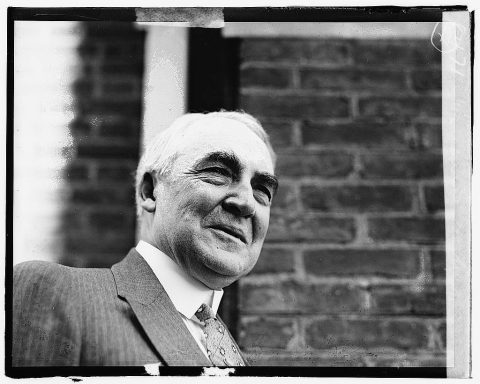

Squires fled on foot and went into hiding, and then emerged to call an election, which he lost in a landslide. During the campaign, one of his longtime allies, the prominent leader of the Fishermen’s Protective Union, openly wished for fascism.

“What is required for Newfoundland and what is most essential for the present conditions is a Mussolini,” said William Coaker.

Months later, with a new government, Newfoundland was on the verge of defaulting on its debt, and the British stepped in.

The vastly oversimplified version is that the British government was concerned that a member of the British Commonwealth defaulting on its debt could have major implications for the whole empire. So the British government bailed out Newfoundland, on the condition that a commission would be struck to investigate the island’s political and economic affairs. Lord Amulree, a British politician, was appointed as chair.

A year later, with the Dominion still teetering on the verge of bankruptcy, the Amulree Report was delivered. It contained this passage, with my emphasis added: “That it was essential that the country should be given a rest from politics for a period of years was indeed recognised by the great majority of the witnesses who appeared before us, many of whom had themselves played a prominent part in the political and public life of the Island.”

Amulree considered the possibility of some sort of national unity government, but could not get past the conclusion that, “Even if a National Government could be established on a basis which led to a suspension of political rivalry, the underlying influences which do so much to clog the wheels of administration and to divert attention from the true interests of the country would continue to form an insuperable handicap to the rehabilitation of the Island.”

In 1934, the Newfoundland House of Assembly voted itself out of existence. It was replaced by a “Commission of Government” which was just six unelected men, appointed by the British. Fifteen years later, Newfoundlanders narrowly voted to join Canada, although to this day conspiracy theories still linger about how democratic the referendum really was.

I am not a Newfoundlander, and I’m hesitant to make any sweeping statements about how Newfoundlanders relate to their own history. But for a decade, I worked as a journalist in St. John’s, covering politics and public affairs. The collapse of democratic self-rule in the 1930s still looms large in the collective identity of the province.