If you’d told somebody in the mid 2000s that David Cameron would become Prime Minister, they would have laughed in your face. If you then told them that a few years later Boris Johnson would be one of his successors, they’d consider you bonkers. This was Blairite Britain – gone were the days of Macmillan, Douglas-Home, and the coterie of other prime ministers educated at that same dusty institution – the hegemony of the Old Etonian was firmly over. Yet Cameron became the 19th Prime Minister educated there, and Boris the 20th, making five out of the fourteen prime ministers elected during Queen Elizabeth II’s reign Old Etonians.

When I first started there, the traditions seemed daunting, and while you had a week of grace period to find your feet, it took a lot longer for the novelty truly to wear off. Dressed in a tailsuit that makes you look like a penguin, and that even the production team of Downton Abbey would question, it’s a complete culture shock. Teachers become “beaks”; homework becomes “EW (short for Extra Work)”, and the threat of “tardy book” (a punishment where you have to get up early to report to the School Office) is ever present. Your life is governed by a tutor, housemaster, and dame (a surrogate mother for your time there, and the most influential person in your day-to-day life), and outside of lessons (known as “schools”) you’re left to your own devices. It’s a sink or swim situation, and some can’t hack the overload of independence.

You’re constantly surrounded by things named after great men who have come before you – whether that be John Maynard Keynes (an economics society) or William Gladstone (a library) – and you can’t help but see yourself as heir to some great dynasty. Sitting in Upper School – a large schoolroom now mainly used for talks by visiting speakers – the walls are lined with marble busts of illustrious Old Etonians past, and it’s not hard to daydream about joining them. In our first ever assembly the head master put it best: “If you know that some interesting people have gone on to do some interesting things, whether it’s George Orwell or the Duke of Wellington, that does implicitly ask the question, why not you?” Success never seems far away, and often you’re regaled with tales about the time your beak caught a famous actor smoking, or how awful a pupil a noted academic once was. Neither does service, particularly when you pass the memorial boards for the First World War (as you do daily on the way to chapel): 1157 Old Etonians died, and 37 Old Etonians have won the Victoria Cross – 17 more than any other school.

In your final years, it’s fun to try and work out who’s going to be most successful after leaving, and – it never seems too outlandish – who among you could be a future prime minister. The people you consider are never confined to a particular group – it’s not “one of the debaters” or “one of the Rugby XV” – in fact, it’s often those who you can’t seem to categorize, or transverse the groups that are most magnetic. To get into Eton, you have to do well in the infamous “List Test”, composed of a computerized assessment and an interview with one of the beaks. For an eleven year old, it can be brutal (one boy left crying midway through our test), particularly as you don’t know what they want: they’re not looking for candidates that fit a particular box. Potential is valued more than current ability, and the greatest asset is that of being interesting. With only one in five getting an offer (odds stiffer than Oxbridge), and after five years of being expected to perform at the highest level, it’s unsurprising that students end up so successful.

Ivo Delingpole, “Boris and the Spirit of Eton”, Die Weltwoche, 2020-01-29.

March 6, 2025

QotD: Old Etonians

January 16, 2025

QotD: “At promise” youth

A new law in California bans the use, in official documents, of the term “at risk” to describe youth identified by social workers, teachers, or the courts as likely to drop out of school, join a gang, or go to jail. Los Angeles assemblyman Reginald B. Jones-Sawyer, who sponsored the legislation, explained that “words matter”. By designating children as “at risk”, he says, “we automatically put them in the school-to-prison pipeline. Many of them, when labeled that, are not able to exceed above that.”

The idea that the term “at risk” assigns outcomes, rather than describes unfortunate possibilities, grants social workers deterministic authority most would be surprised to learn they possess. Contrary to Jones-Sawyer’s characterization of “at risk” as consigning kids to roles as outcasts or losers, the term originated in the 1980s as a less harsh and stigmatizing substitute for “juvenile delinquent”, to describe vulnerable children who seemed to be on the wrong path. The idea of young people at “risk” of social failure buttressed the idea that government services and support could ameliorate or hedge these risks.

Instead of calling vulnerable kids “at risk”, says Jones-Sawyer, “we’re going to call them ‘at-promise’ because they’re the promise of the future”. The replacement term — the only expression now legally permitted in California education and penal codes — has no independent meaning in English. Usually we call people about whom we’re hopeful “promising”. The language of the statute is contradictory and garbled, too. “For purposes of this article, ‘at-promise pupil’ means a pupil enrolled in high school who is at risk of dropping out of school, as indicated by at least three of the following criteria: Past record of irregular attendance … Past record of underachievement … Past record of low motivation or a disinterest in the regular school program.” In other words, “at-promise” kids are underachievers with little interest in school, who are “at risk of dropping out”. Without casting these kids as lost causes, in what sense are they “at promise”, and to what extent does designating them as “at risk” make them so?

This abuse of language is Orwellian in the truest sense, in that it seeks to alter words in order to bring about change that lies beyond the scope of nomenclature. Jones-Sawyer says that the term “at risk” is what places youth in the “school-to-prison pipeline”, as if deviance from norms and failure to thrive in school are contingent on social-service terminology. The logic is backward and obviously naive: if all it took to reform society were new names for things, then we would all be living in utopia.

Seth Barron, “Orwellian Word Games”, City Journal, 2020-02-19.

December 11, 2024

QotD: Simon Leys on George Orwell

… the very title of one of his essays, “The Art of Interpreting Non-Existent Inscriptions Written in Invisible Ink on a Blank Page”, tells you the essentials of what you needed to know about the decipherment of publications coming out of China and the kind of regime that made such an arcane art necessary, and why anyone who took official declarations at face value was at best naive and at worst a knave or a fool.

What Leys wrote in 1984 in a short book about George Orwell might just as well have been written about him: “In contrast to certified specialists and senior academics, he saw the evidence in front of his eyes; in contrast to wily politicians and fashionable intellectuals, he was not afraid to give it a name; and in contrast to the sociologists and political scientists, he knew how to spell it out in understandable language.”

Leys drew a distinction between simplicity and simplification: Orwell had the first without indulgence in the second. Again, the same might be said of Leys — who, of course, like Orwell, had taken a pseudonym, and with whose work there were many parallels in his own.

But immense as was Leys’s achievement in destroying the ridiculous illusions of Western intellectuals, as Orwell had tried to do before him, it was a task thrust upon him by circumstance rather than one that he would have chosen for himself. He was by nature an aesthete and a man of letters, and I confess that great was my surprise (and pleasurable awe) when I discovered that he was, in addition to being a great sinologist, a great literary essayist.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Rare and Common Sense”, First Things, 2017-11.

November 26, 2024

Orwell is more relevant now than at any time since his death

I’m delighted to find that Andrew Doyle shares my preference for Orwell the essayist over Orwell the novelist:

It is not without justification that Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) have become the keystones of George Orwell’s legacy. Personally, I’ve always favoured his essays, more often quoted than read in full. I recently wrote an article about his essays for the Washington Post, focusing on their relevance to today’s febrile political climate. You can read the article here. I would draw particular attention to the multitude of comments from left-wing readers who are apparently outraged at my argument (actually, Orwell’s argument) that authoritarianism is not specific to any one political tribe. They seem oddly determined to prove the point.

Orwell is unrivalled on the topic of the human instinct for oppressive behaviour, but his essays are far more wide-ranging than that. In these little masterworks, one senses a great thinker testing his own theses, forever fluctuating, refining his views in the very act of writing. The essays span the last two decades of his life, offering us the most direct possible insight into this unique mind.

[…]

I find Orwell’s disquisitions on literature to be among his most rewarding. “All art is propaganda”, he declares in his extended piece on Charles Dickens (1940) [link]. This conviction, flawed as is it, accounts for his determination to focus less on Dickens’s literary merits and more on his class consciousness, which is found wanting. Even better is Orwell’s rebuttal to Tolstoy’s strangely literal-minded reading of Shakespeare (1947’s “Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool” [link]), which is so rhetorically deft that it seems to settle the matter for good.

Another impressive essay, “Inside the Whale” (1940) [link], opens with a glowing assessment of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer (1935) but soon broadens its range to cover many contemporary novelists and their approach to social commentary. The title is a reference to Miller’s remarks on the Biblical tale of Jonah, suggesting that life inside the whale has much to recommend it. Orwell puts it this way:

There you are, in the dark, cushioned space that exactly fits you, with yards of blubber between yourself and reality, able to keep up an attitude of the completest indifference, no matter what happens.

Orwell invites us to imagine that the whale is transparent, and so writers of Miller’s ilk may snuggle contentedly within, observing without interacting, recording snapshots of the world as it bounces by. This kind of inaction is anathema to Orwell, whose every written word seems to be driving towards the enactment of social change.

Orwell’s essays often serve as a cudgel to batter his detractors. He dislikes homosexuals, or those “fashionable pansies” who lack the masculine vigour to take up arms in defence of their country. He displays a similar lack of patience for the imperialistic middle-class “Blimps” and the anti-patriotic left-wing intelligentsia, or indeed anyone who adheres slavishly to any given political ideology. His work bears much of the stamp of the old left; that mix of social conservatism and economic leftism that we see most powerfully expressed in his 1941 essay “The Lion and the Unicorn” [link]. Bad writing is also a recurring bugbear; Orwell’s loathing of cliché and “ready-made metaphors” is one of the reasons his own prose style is so effervescent.

[…]

When Orwell pessimistically refers to “the remaining years of free speech”, one cannot help but be reminded of the increasingly authoritarian tendencies of today’s British government. He expresses irritation that more writers are not wielding their pens in the service of improving society. His own work, by contrast, is what he would term “constructive”, profoundly moral, and purposefully crafted in the hope of actuating real-world change. While other writers resigned themselves to a life inside the whale, Orwell was determined to cut his way out.

July 27, 2024

Cancelling Orwell (again)

In The Daily Sceptic, Paul Sutton recounts a recent discussion with some Oxford graduate students where the topic of George Orwell came up:

The students maintained that the important thing is quality of writing but, paradoxically, this can only be judged by a strict contemporary “evaluation” of any Right-wing or outdated views. Inevitably, this contextualisation then reveals that said writers are “problematic” and “not as good as XYZ” – usually some figure who fits their sensibilities, and coincidentally one who’s almost always female – or at least better suited to the diversity required by these commissars.

So far, so well known and wearily familiar. The absolute impossibility of literature under such a mindset – one enthusiastically endorsed by graduate students who professed to live for literature – is utterly depressing. We’re in effect dealing with its cancellation.

I made a perfunctory effort in observing their complete inconsistency, but things got more interesting when Orwell was discussed. Of course, Orwell famously wrote against their stand, not least in his brilliant defence of Kipling’s literary merit and his refusal to allow orthodoxy to dictate his aesthetic preferences, in “Benefit of Clergy“.

Unfortunately, Orwell’s stint in the Burmese Imperial Police made him a despicable figure to the students, little better than a Waffen SS or Gestapo officer. True, he’d belatedly retrieved himself by his “eventual writing” in the 1940s, but he’d spent many years performing the dirty work of the British Empire. His famous essay, “A Hanging“, showed him enthusiastically hands on at it.

I’d honestly never heard such a narrow and limited view, and was intrigued. As a preposterous misrepresentation, it needs little rebuttal. “A Hanging” is indeed a brilliantly disturbing account of an Indian murderer being hanged, a man who’d have been executed at that time in any country. The essay explores the deep unease Orwell felt about his role, so it’s a lie to claim it shows him uncritically doing his job, let alone revelling in his exertion of British authority.

Such an interpretation shows a shocking lack of understanding. As does the idea that Orwell only recanted any pro-Imperial views in the 1940s; his underrated Burmese Days was published in 1934 and he wrote extensively about his disgust for the job he did in the late 20s and 1930s. Of course, he didn’t only feel disgust, nor would he pretend that the British brought only misery and were unique as imperial exploiters.

What I’m most interested in is how an alternative Orwell was then offered up, a writer who’d accepted the British Empire was “problematic” yet offered a nice comforting view of how nice and comforting life can be – if you agree with the progressives, that is.Step forward Jan Morris and his trilogy Pax Britannica. Now, I haven’t read this non-fictional account of the British Empire but from background knowledge, it’s not in any way a replacement for Orwell or even remotely comparable. It’s an exhaustive historical work, not a personal creative one. But this trilogy was extolled by the students as what Orwell should have done when discussing empire. There was the implication that Orwell could now be – somewhat thankfully – ignored.

Bizarrely, the Englishman then introduced Joyce, first saying that the man was a lifelong sponger who’d have probably fleeced him, but as a writer was the very model of a pan-European, liberal and open to all cultures. Again, the grubby contradictions and sheer banality of such a perspective are eye-popping – from a DPhil student in perhaps the country’s finest university.

And I’ve a nagging feeling that Jan Morris – a famous case of gender realignment (he “transitioned” to female in 1972) – was picked for the “acceptable author” reasons. That’s the problem with “author context” vetting – as with “diversity hires”. Much as I’ve enjoyed Morris’s travel writing, especially Oxford, it’s staggering for this author to be proposed as some alternative to Orwell! Not only in terms of obvious lesser importance, but they’re not remotely comparable in terms of genre or aims. How could any serious reader – let alone one at a leading university – talk such gibberish?

July 23, 2024

July 17, 2024

QotD: “Orwellian”

All writers enjoying respect and popularity in their lifetimes entertain the hope that their work will outlive them. The true mark of a writer’s enduring influence is the adjectification of his (sorry, but it usually is “his”) name. An especially jolly Christmas scene is said to be “Dickensian”. A cryptically written story is “Hemingwayesque”. A corrupted legal process gives rise to a “Kafkaesque” nightmare for the falsely accused. A ruthless politician takes a “Machiavellian” approach to besting his rival.

But the greatest of these is “Orwellian”. This is a modifier that The New York Times has declared “the most widely used adjective derived from the name of a modern writer … It’s more common than ‘Kafkaesque’, ‘Hemingwayesque’ and ‘Dickensian’ put together. It even noses out the rival political reproach ‘Machiavellian’, which had a 500-year head start.”

Orwell changed the way we think about the world. For most of us, the word Orwellian is synonymous with either totalitarianism itself or the mindset that is eager to employ totalitarian methods — notably the bowdlerization or suppression of speech and freedoms — as a hedge against popular challenge to a politically correct vision of society dictated by a small cadre of elites.

Indeed, it was thanks to Orwell’s books — forbidden, acquired by stealth and owned at peril — that many freedom fighters suffering under repressive regimes, found the inspiration to carry on their struggle. In his memoir, Adiós Havana, for example, Cuban dissident Andrew J. Memoir wrote, “Books such as … George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984 became clandestine bestsellers, for they depicted in minute detail the communist methodology of taking over a nation. These […] books did more to open the eyes of the blind, including mine, than any other form of expression.”

Barbara Kay, “The way they teach Orwell in Canada is Orwellian”, The Post Millennial, 2019-11-29.

June 16, 2024

June 12, 2024

“Consumption inequality” really has fallen significantly since Orwell’s day

Tim Worstall on some of the points raised by Christopher Snowdon’s new introduction to Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four:

Eric Blair, the useful one, once pointed out that:

In a world in which everyone worked short hours, had enough to eat, lived in a house with a bathroom and a refrigerator, and possessed a motor-car or even an aeroplane, the most obvious and perhaps the most important form of inequality would already have disappeared. If it once became general, wealth would confer no distinction.

That’s from Chris Snowdon’s new intro to 1984 – you should buy a copy.

Not that Eric knew enough economics to know this but what he’s talking about is consumption inequality.

Sure, we’ve Oxfam squealing that wealth inequality is rising summat fearsome. It ain’t — they fail to account for what we already do to reduce wealth inequality. Many tell us that income inequality is rising summat fearsome. It ain’t. Global income inequality has been falling this past 40 years and as all men are indeed brothers it’s the global number that matters.

But the one that’s really fallen like a stone is that consumption inequality. Consumption is also really the only one of the three that matters. Sure, a world in which there are those without three squares and a crib is not a good one. But once all do have three squares etc. then whatever other inequality there is is, well, it’s not actually all that important is it?

[…]

We really have got to what Orwell thought would be equality. In 1930s England (which was his mental reference point) all of these things – all – were signifiers of significant wealth or income:

As a poorer country the UK was a little behind on these things but my best guess would be that we’re ahead of the US on washing machines today (the US still has a habit of communal machines in apartment blocks). And it amuses that central heating isn’t even on the list. This was something very middle class indeed in the 1960s, really only became “normal” in the UK in the late 70s into the 80s. As with double glazing. These days you’re defined as being in fuel poverty if you cannot heat your house, always and all of it, to a level that no one at all could before that central heating. No, really, coal fire heated houses might average 10oC in winter and that would only be in rooms with an actual fire — others would be at 0oC.

This is not to get into a Four Yorkshiremen but people would be astonished at how cold houses were 1970s and earlier. My own arrival in the US in 1981 had me wondering how they had heating systems that heated all the house, properly, all winter. How could anyone afford that?

June 10, 2024

QotD: The British sweet tooth

It will be seen that British cookery displays more variety and more originality than foreign visitors are usually ready to allow, and that the average restaurant or hotel, whether cheap or expensive is not a trustworthy guide to the diet of the great mass of the people. Every style of cookery has its peculiar faults, and the two great shortcomings of British cookery are a failure to treat vegetables with due seriousness, and an excessive use of sugar. At normal times the average consumption of sugar per head is very much higher than in most countries, and all British children and a large proportion of adults are over-much given to eating sweets between meals. It is, of course, true that sweet dishes and confectionery – cakes, puddings, jams, biscuits and sweet sauces – are the especial glory of British cookery but the national addiction to sugar has not done the British palate any good. Too often it leads people to concentrate their main attention on subsidiary foods and to tolerate bad and unimaginative cookery in the main dishes. Part of the trouble is that alcohol, even beer, is fantastically expensive and has therefore come to be looked on as a luxury to be drunk in moments of relaxation, not as an integral part of the meal. The majority of people drink sweetened teas with at least two of their daily meals, and it is therefore only natural that they should want the food itself to taste excessively sweet. The innumerable bottled sauces and pickles which are on sale in Britain are also enemies of good cookery. There is reason to think, however, that the standard of British cookery – that is, cookery inside the home – has gone up during the war years, owing to the drastic rationing of tea, sugar, meats and fats. The average housewife has been compelled to be more economical then she used to be, to pay more attention to the seasoning of soups and stews, and to treat vegetables as a serious foodstuff and less a neglected sideline.

George Orwell, “British Cookery”, 1946. (Originally commissioned by the British Council, but refused by them and later published in abbreviated form.)

May 7, 2024

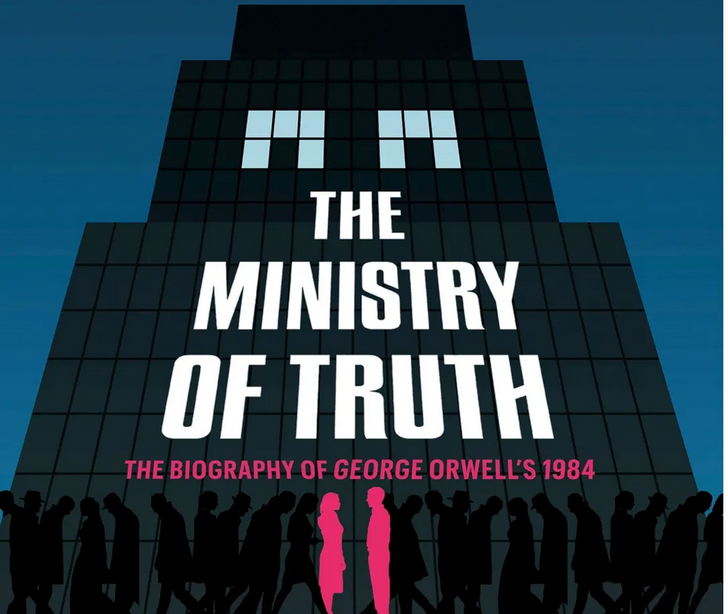

Charles Holden and the Ministry of Truth

Jago Hazzard

Published Jan 28, 2024The strange connection between George Orwell and the London Underground.

April 28, 2024

QotD: “I love Big Brother!”

I suppose my defeatist attitude is precisely what they — they being governments and corporations — are trying to cultivate with all of this oppression.

I don’t relish the Winston Smith role. I’ll just pass on the rats in Room 101 and skip right to the mindless, thoughtless bliss of Big Brotherly love without having to have it beaten into me.

Actually, it seems that Orwell was mistaken. Oppression does not have to mean dismal living conditions, horrible food, telescreen propaganda and rusty rationed razor blades. Big government can control people far more effectively by giving them a small slice of comfort and domesticity. Allow them a modest home. Encourage them to accumulate trinkets and toys and the occasional status symbol. Allow commercial marketing to develop the propaganda that shapes opinion and mood and sets people on the desired path.

Commercial marketing is far more effective than state propaganda — “Drivers Wanted” has recruited more people than any poster featuring a stern and serious Uncle Sam. Keep them somewhat comfortable, keep them acquisitive rather than inquisitive, keep them entertained rather than informed — and no-one will be seriously tempted to pursue an alternative.

Jonathan Piasecki, private e-mail, 1999-07-07 (originally published, with permission, on the old blog, 2005-06-24).

March 16, 2024

Orwell – The New Life (DJ Taylor in discussion with Les Hurst)

The Orwell Society

Published Jun 9, 2023DJ Taylor discusses his new biography of Orwell with Les Hurst

Part 2:

The Orwell Society

Published Jun 26, 2023DJ Taylor answers questions and discusses issues raised by Orwell Society members.

March 13, 2024

March 1, 2024

Understanding the modern media

It’s hard for Baby Boomers and even some older Gen X folks to grasp just how much the mainstream media has changed since the 1960s and 70s. Helpfully, Severian provides the context to properly understand what drives them and why they do the things they do:

Proposed coat of arms for Founding Questions by “urbando”.

The Latin motto translates to “We are so irrevocably fucked”.

There is no local news, because all “news” is Apparat audition tape. Back when — back when they were called “reporters” — news people had a clear career progression within a specific industry. A hungry young reporter for the Toad Suck, Nebraska, Times-Picayune might end his days as a reporter for the New York Times or Washington Post, but that was as high as he could reasonably expect to go. Same with the television division — the bobblehead at WSUX in Toad Suck might end up, at most, on CNN or Fox.

These days, though, they call themselves “journalists”, and “journalist” is just an entry-level Apparat post. They’re not just auditioning for the NYT or CNN, of course. A hungry young “journalist” might end xzhyr career at either, of course, but also as a corporate communications director, a political campaign consultant, a professor of “journalism”, a Diversity Outreach Coordinator, any one of a million “Media strategies” and “Media consulting” gigs … or, of course, as an outright lobbyist, because all of those are just euphemisms for “lobbying” anyway.

And that’s before you consider that all the “independent” papers and stations have been bought up by huge conglomerates, and depend on advertising revenue. Noam Chomsky was right — the Media does dance to the tune its corporate paymasters’ call. He was just wrong on those paymasters’ political orientation. Combine all that, and even the most straight-up, just-the-facts-ma’am local “news” story will find some way to insert The Sermon. If you don’t see The Sermon, you’ve either found an incompetent journalist (which happens) … or you might be looking at something subtle.

[…]

The Media, like Skynet, is self-aware. This significantly complicates the stoyachnik‘s task, as The Media understands its own power, and it increasingly wants to drive Narratives itself, especially as its power is on the verge of… well, not collapse exactly, but certainly a sea change. Because The Media is not monolithic, and that’s part of its self-awareness. So many “journalists” do nothing but hit refresh on Twitter all day, and Twitter knows this — that makes Twitter the real power broker. Google, too, obviously is more self-aware than traditional Media. That ludicrous AI image generator represents years of effort; they expended enormous resources to get precisely that result. They understand how utterly dependent the lower layers of The Media are on them; they are more self-aware.

Let us […] use Google’s own AI “summarizer” to refamiliarize ourselves with the tale of Comrade Ogilvy:

Comrade Ogilvy is an imaginary character in the novel 1984, created by Winston Smith to replace Comrade Withers, an Inner Party member who has fallen into disgrace and been vaporized. Comrade Ogilvy supposedly lived a patriotic and virtuous life, supported the party as a child, designed a highly effective hand grenade as an adult, and died in action at the age of 23 while protecting important dispatches for his country. He did not drink or smoke, was celibate, and only conversed about Party philosophy, Ingsoc. Comrade Ogilvy displays how easy it is for a member of The Party to be pulled from thin air, and how determined The Party is to keep unpersons from the media.

The Apparatchiks at Google are more self-aware than the Apparatchiks at, say, the New York Times. That is, they understand their place in the Apparat better, and see the networks more clearly. They know how mal-educated “journalists” are, far better than the “journalists” themselves do. Google, like Winston Smith, knows full well that there’s no Comrade Ogilvy. But the “journalists” at the New York Times who are utterly reliant on Google for their “facts” do NOT know this. How could they?

And thus, the only White people in all of human history were Nazis. At least according to Google’s AI image generator, and therefore — soon enough — it’s what “everybody knows”. (And it’s necessarily recursive. The second generation of Google engineers will not know there’s no Comrade Ogilvy, any more than the current generation of “journalists” does).