HardThrasher

Published 29 Nov 202402:00 – Here We Go Again

06:36 – Perfect Planning

13:16 – Death of a Prophet

14:51 – The Fly In

18:56 – Dazed and Confused (in the Monsoon)

20:40 – Can’t Fly in This

31:54 – Survivor’s ClubPlease consider donations of any size to the Burma Star Memorial Fund who aim to ensure remembrance of those who fought with, in and against 14th Army 1941–1945 — https://burmastarmemorial.org/

(more…)

November 30, 2024

Forgotten War Ep 5 – Chindits 2 – The Empire Strikes

November 18, 2024

QotD: Napoleon and his army

To me the central paradox of Napoleon’s character is that on the one hand he was happy to fling astonishing numbers of lives away for ultimately extremely stupid reasons, but on the other hand he was clearly so dedicated to and so concerned with the welfare of every single individual that he commanded. In my experience both of leading and of being led, actually giving a damn about the people under you is by far the most powerful single way of winning their loyalty, in part because it’s so hard to fake. Roberts repeatedly shows us Napoleon giving practically every bit of his life-force to ensure good treatment for his soldiers, and they reward him with absolutely fanatical devotion, and then … he throws them into the teeth of grapeshot. It’s wild.

Napoleon’s easy rapport with his troops also gives us some glimpses of his freakish memory. On multiple occasions he chats with a soldier for an hour, or camps with them the eve before a battle; and then ten years later he bumps into the same guy and has total recall of their entire conversation and all of the guy’s biographical details. The troops obviously went nuts for this kind of stuff. It all sort of reminds me of a much older French tradition, where in the early Middle Ages a feudal lord would (1) symbolically help his peasants bring in the harvest and (2) literally wrestle with his peasants at village festivals. Back to your point about the culture, my anti-egalitarian view is that that kind of intimacy across a huge gulf of social status is easiest when the lines of demarcation between the classes are bright, clear, and relatively immovable. What’s crazy about Napoleon, then, is that despite him being the epitome of the arriviste he has none of the snobbishness of the nouveaux-riches, but all of the easy familiarity of the natural aristocrat.

True dedication to the welfare of those under your command,1 and back-slapping jocularity with the troops, are two of the attributes of a wildly popular leader. The third2 is actually leading from the front, and this was the one that blew my mind. Even after he became emperor, Napoleon put himself on the front line so many times he was practically asking for a lucky cannonball to end his career. You’d think after the fourth or fifth time a horse was shot out from under him, or the guy standing right next to him was obliterated by canister shot, the freaking emperor would be a little more careful, but no. And it wasn’t just him — the vast majority of Napoleon’s marshals and other top lieutenants followed his example and met violent deaths.

This is one of the most lacking qualities in leaders today — it’s so bad that we don’t even realize what we’re missing. Obviously modern generals rarely put themselves in the line of fire or accept the same environmental hardships as their troops. But it isn’t just the military, how many corporate executives do you hear about staying late and suffering alongside their teams when crunch time hits? It does still happen, but it’s rare, and the most damning thing is that it’s usually because of some eccentricity in that particular individual. There’s no systemic impetus to commanders or managers sharing the suffering of their men, it just isn’t part of our model of what leadership is anymore. And yet we thirst for it.

Jane and John Psmith, “JOINT REVIEW: Napoleon the Great, by Andrew Roberts”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-01-21.

1. When not flinging them into the face of Prussian siege guns.

2. Okay, there are more than three. Some others include: deploying a cult of personality, bestowing all kinds of honors and awards on your men when they perform, and delivering them victory after victory. Of course, Napoleon did all of those things too.

November 10, 2024

The 1896 US Presidential election

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte looks back to the 1896 contest between William McKinley and William Jennings Bryan:

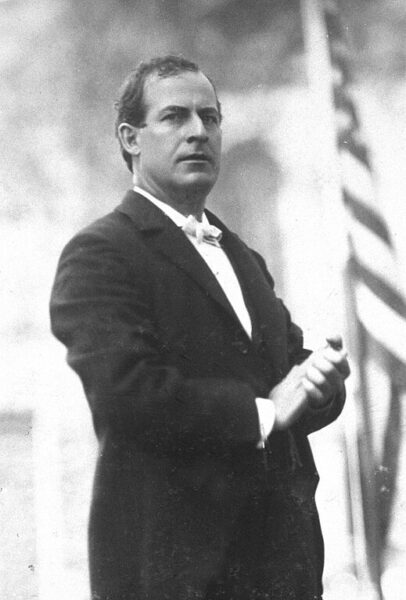

William Jennings Bryan, Democratic party presidential candidate, standing on stage next to American flag, 3 October 1896.

LOC photo LC-USZC2-6259 via Wikimedia Commons.

The 1880s and 1890s saw an enormous expansion in the number of newspapers in America. New printing technologies had drastically reduced barriers to entry in the newspaper field, while the emergence of consumer advertising was making the business more lucrative. By the election of 1896, there were forty-eight daily newspapers in New York (Brooklyn had several more), each vying for the attention of some portion of the city’s three million souls. The major papers routinely produced three or four editions a day, and as many as a dozen on a hot news day, making for a 24/7 news environment long before the term was coined. The individual newspapers were distinguished by their politics, ethnic, and class orientations. They advocated vigorously, often shamelessly, and occasionally dishonestly for the interests of their readers. Similar dynamics were afoot everywhere. America, in the 1890s, was noisy as hell.

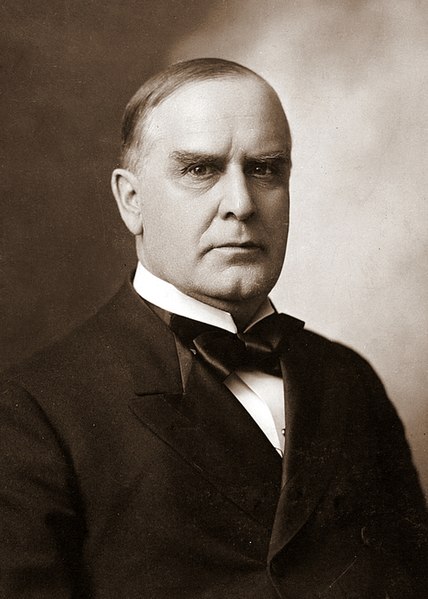

Republican nominee William McKinley was the respectable candidate in 1896, heavily favoured. He had a state-of-the-art organization, buckets of money, and vast newspaper support, even among important Democratic publishers such as Joseph Pulitzer. The Democrats fielded William Jennings Bryan, who looked to be the weak link in his own campaign. He was a relatively unknown and untested ex-congressman from Nebraska, just thirty-six-years-old, a messianic populist with a mesmerizing voice and radical views. A last-minute candidate, he was selected on the convention floor over Richard P. Bland, against the protests of the party establishment.

Bryan broke all the norms of politics in 1896. At the time, it was believed that the dignified approach to campaigning was to sit on one’s porch and let party professionals speak on one’s behalf. Grover Cleveland had made eight speeches and journeyed 312 miles in his three presidential campaigns (1884, 1888, 1892). Bryan spent almost his entire campaign on the rails, holding rallies in town after town. He travelled 18,000 miles and talked to as many as five million Americans. He unabashedly championed the indigent and oppressed against Wall Street and Washington elites.

Inflation was the central issue of the 1896 campaign. The US was on the gold standard at the time, meaning that the amount of money in circulation was limited by the amount of gold held by the treasury. Gold happened to be scarce, resulting in an extended period of deflation, a central factor in the major economic depression of the early 1890s. The effects were felt disproportionately by the poor and working class. Bryan advocated the monetization of silver (in addition to gold) as a means of increasing the money supply and reflating the economy. This was viewed by the establishment as an economic heresy (not so much today). Bryan was viewed as a saviour by his followers, and that’s certainly how he saw himself.

The New York Sun heard among the Democrats “the murmur of the assailants of existing institutions, the shriek of the wild-eyed”. The New York Herald warned that Bryan’s supporters, disproportionately in the west and south, represented “populism and Communism” and “crimes against the nation” on par with secession. The New York Tribune warned that the Democrats’ “burn-down-your-cities platform” would lead to pillage and riot and “deform the human soul”. The New York Times asked, in all sincerity, “Is Mr. Bryan Crazy?” and spoke to a prominent alienist who was convinced that the election of the Democrat would put “a madman in the White House”. That Bryan’s support was especially strong among new Americans — the nation was amid an unprecedented wave of immigration — was especially disconcerting to the establishment. His followers were a “freaky”, “howling”, “aggregation of aliens”, according to the Times.

The only major New York newspaper to support the Democrats that season was Hearst’s New York Journal, a new, inexpensive, and wildly popular daily. I wrote about this in The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst. Loathed by the afore-mentioned respectable sheets, the Journal became the de facto publicity arm of the Bryan campaign and Hearst became the Elon Musk of his time.

The unobjectionable McKinley didn’t offer Democrats much of a target, but his campaign was being managed and funded by Ohio shipping and steel magnate Mark Hanna. The Journal had learned that Hanna and a syndicate of wealthy Republicans had previously bailed out McKinley from a failed business venture. Hearst’s cartoonists portrayed Hanna as a rapacious plutocratic brute (accessorized with bulging sacks of money or the white skulls of laborers) and McKinley as his trained monkey or puppet: “No one reaches the McKinley eye or speaks one word to the McKinley ear without the password of Hanna. He has McKinley in his clutch as ever did hawk have chicken … Hanna and his syndicate are breaking and buying and begging and bullying a road for McKinley to the White House. And when he’s there, Hanna and the others will shuffle him and deal him like a deck of cards.” The cartoons were criticized as cruel, distorted, and perverted. They were hugely effective.

Caught off guard by Bryan’s tactics, but unwilling to put McKinley on the road, Hanna instead arranged for 750,000 people from thirty states to visit Canton, Ohio and see McKinley speak from his front porch. He meanwhile made some of the most audacious fundraising pitches Wall Street had ever heard. Instead of asking for donations, he “levied” banks and insurers a percentage of their assets, demanding the Carnegies, Rockefellers, and Morgans pay to defend the American way from democratic monetary lunatics. Standard Oil alone coughed up $250,000 (the entire Bryan campaign spent about $350,000). Hanna printed and distributed a mind-boggling 250 million documents to a US population of about 70 million (the mails were the social media of the day), and fielded 1,400 speakers to spread the Republican gospel from town to town. All of this was unprecedented.

The Republicans generated their own conspiracy theories to counter the stories about Hanna’s controlling syndicate. Pulitzer’s New York World published a series of articles on The Great Silver Trust Conspiracy — “the richest, the most powerful and the most rapacious trust in the United States”. Bryan was said to be a puppet of this “secret silver society”, for which the World had no evidence beyond that the candidate was popular in silver mining states.

There were violent motifs throughout the campaign. The Republicans accused the Democrats of fostering division and rebellion, threatening national unity by pitting the south and the west against the east and the Mid-West. This was charged language with the Civil War still in living memory. Hanna funded a Patriotic Heroes’ Battalion comprising Union army generals who held 276 meetings in the last months of the campaign. They would ride out in full uniforms to a bugle call, advising the old soldiers who came out to see them to “vote as they shot”. Said one of their number: “The rebellion grew out of sectionalism … We cannot tolerate, will not tolerate, any man representing any party who attempts again to disregard the solemn admonitions of Washington to frown down upon any attempt to set one portion of the country against another.” Senior New York Republicans vowed that if the Democrats were elected, “we will not abide the decision”. These belligerent tactics were cheered by the majority of New York papers.

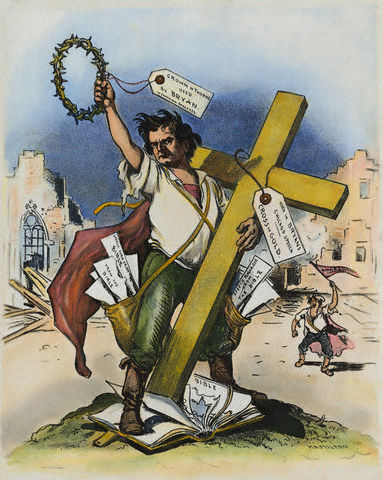

Democratic and populist leader William Jennings Bryan, climaxed his career when when he gave his famous “Cross of Gold” speech which won him the nomination at the age of 36.

Grant Hamilton cartoon for Judge magazine, 1896 via Wikimedia Commons.Bryan did nothing to cool tempers by claiming, in his famous “cross of gold” speech, that he and working-class Americans were being crucified by financial and political elites.

On it went. There were many echoes of 1896 in 2024. The polarized electorate, the last-minute candidate, record spending, unprecedented campaign tactics, populism and personal charisma, relentless ad hominem attacks, class and culture and regional warfare, inflation, immigration, racism, misinformation and conspiracy theories, comedians and plutocrats, threats of authoritarianism and violence and revolution, all of it massively amplified, and sometimes generated, by messy new media.

Of course, some of the echoes are coincidental, and there are also many contrasts. It was a different electorate. The alignment of the parties bore little resemblance to what we see today. Bryan, aside from his megalomania and zealotry, was as personally decent as Trump isn’t. And Bryan lost the campaign.

My point is I don’t think it’s an accident that the likes of Bryan and Trump — mavericks who thoroughly dominate their parties (both thrice nominated) through a direct and unshakeable bond with their followers — surface when the public sphere is most chaotic. New media environments, by their nature, are amateurish, turbulent, unsettling. There are fewer guardrails, which is a major reason outsiders and their followers gravitate to them. They see a way to change the rules and end-run established media (establishment candidates are naturally more comfortable using established channels to reach voters). New forms of political communication develop, contributing to new political norms, tactics, and strategies, and long-lasting political realignments.

For better or worse.

The Sixties, Cicero, Catiline, Cato and Caesar – The Conquered and the Proud Episode 9

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published Jul 3, 2024Continuing our series on the the history of Rome from 200 BC to AD 200, this time we look at the turbulent decade following the consulship of Pompey and Crassus in 70 BC. These years saw Pompey being given major commands against the pirates and Mithridates. Men like Cicero, Caesar and Cato were on the ascendant. Cicero’s letters can make the decade seem calm, but further consideration reveals the threat and reality of political violence, seen most of all in Catiline’s conspiracy which led to a brief civil war.

In this talk we explore the themes we have already considered and consider how imperial expansion continued to change the Roman Republic.

This talk will be released in July — and as this is the month named after Julius Caesar, it seemed only appropriate to have a Caesar theme to most of the talks.

Next time we will look at the Fifties BC and the start of the Civil War in 49 BC.

November 9, 2024

Bill C-413 “is aimed at preventing her fellow Canadians from saying anything positive about Indian residential schools”

Nina Green suggests that Bill C-413’s sponsor might be the first person in Canada to face criminal charges in that piece of legislation if her private member’s bill gets Royal Assent:

On 31 October 2024 Member of Parliament Leah Gazan called a press conference to lobby for Bill C-413, her private member’s bill designed to criminalize her fellow citizens for disagreeing with her views.

Gazan led off the press conference with this statement:

Good morning, everybody. I’m Leah Gazan, and I’m the Member of Parliament from Winnipeg Centre, and we’re here to discuss support of Bill C-413 to amend the Criminal Code to include the willful promotion of hate against Indigenous peoples by condoning, downplaying, justifying the residential schools.

To evoke an emotional response, Gazan used the word “violence” a dozen times during her press conference, falsely equating speech with violence, although violence by definition involves physical force.

Gazan’s bill is obviously not aimed at preventing physical violence against Indigenous people. It is aimed at preventing her fellow Canadians from saying anything positive about Indian residential schools.

Earlier, on 27 September 2024, Gazan made the bill personal, telling CTV News that “my family has been impacted by residential school”, implying that she had been motivated to introduce her bill because of the serious harm residential schools had inflicted on her own family.

In fact, the exact opposite is true. Residential schools had a positive effect on Leah Gazan’s family.

On her father’s side, Gazan is Jewish, and her maternal grandfather was Chinese. Thus her only possible connection to Indian residential schools is through her maternal grandmother, Adeline LeCaine, the daughter of Leah Gazan’s great-grandfather, John LeCaine (1890-1964).

What we learn about John LeCaine turns out to be surprising. He was the son of a white North West Mounted Police officer, William Edward Archibald LeCain (1859-1915), and Emma Loves War, whose Lakota Sioux family sought refuge in Canada with Chief Sitting Bull and 5000 of his people after the massacre of Custer and his men at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. […]

Since he had a white father and an American Indian mother, John LeCaine was, in the terminology of the day, a half-breed, and ineligible to attend a residential school since federally-funded Indian residential schools were reserved for status Indians under the Indian Act. However an exception was made, and both John LeCaine and his sister Alice LeCaine (1888-1976) were admitted to the Regina Industrial School. John LeCaine attended for seven years, from 1899 to 1906 when he was 9 to 16 years of age. While there he learned to read and write English proficiently, and mastered agricultural and carpentry skills which equipped him to apply, like white settlers at the time, for a homestead, which he proved up in 1913. In 1914 he wrote to the Department of the Interior asking for a ruling on whether his two half-brothers — who were full-blooded Sioux — could also apply for homesteads.

The proficiency in English he acquired at the Regina Industrial School enabled John LeCaine to became a writer and a historian of the Lakota people. In later years he mapped the places he and his stepfather, Okute Sica, had visited on a journey to the Frenchman River in 1910, and wrote a collection of stories told to him by Sioux Elders, Reflections of the Sioux World, as well as other articles, including some published in the Oblate journal, The Indian Record.

QotD: George Bernard Shaw

… Shaw is not at all the heretic his fascinated victims see him, but an orthodox Scotch Presbyterian of the most cock-sure and bilious sort. In the theory that he is Irish I take little stock. His very name is as Scotch as haggis, and the part of Ireland from which he comes is peopled almost entirely by Scots. The true Irishman is a romantic; he senses religion as a mystery, a thing of wonder, an experience of ineffable beauty; his interest centers, not in the commandments, but in the sacraments. The Scot, on the contrary, is almost devoid of that sort of religious feeling; he hasn’t imagination enough for it; all he can see in the Word of God is a sort of police regulation; his concern is not with beauty but with morals. Here Shaw runs true to type. Read his critical writings from end to end, and you will not find the slightest hint that objects of art were passing before him as he wrote. He founded, in England, the superstition that Ibsen was no more than a tin-pot evangelist — a sort of brother to General Booth, Mrs. Pankhurst, Mother Eddy and Billy Sunday. He turned Shakespeare into a prophet of evil, croaking dismally in a rain-barrel. He even injected a moral content (by dint of abominable straining) into the music dramas of Richard Wagner, surely the most colossal slaughters of all moral ideas on the altar of beauty ever seen by man. Always this ethical obsession, the hall-mark of the Scotch Puritan, is visible in him. He is forever discovering an atrocity in what has hitherto passed as no more than a human weakness; he is forever inventing new sins, and demanding their punishment; he always sees his opponent, not only as wrong, but also as a scoundrel. I have called him a good Presbyterian.

H.L. Mencken, “Shaw as Platitudinarian”, The Smart Set, 1916-08.

November 8, 2024

QotD: David Lloyd George and the British Liberal Party

Lloyd George is one of the most obviously fascinating figures in modern British political history, for three reasons. The first is his background. The Liberal Party, since its formal inception in 1859, had always responded to a touch of the purple. Lord Palmerston was a viscount; Lord John Russell was the son of a duke; William Gladstone was Eton and Christ Church; Lord Rosebery was Lord Rosebery; Henry Campbell-Bannerman and H.H. Asquith at least went to Trinity, Cambridge and Balliol, Oxford respectively.

Lloyd George was from nowhere. He grew up in Llanystumdwy, Caernarfonshire, where he lived in a compact cottage with his mother, uncle, and siblings, and was trained as a solicitor in Porthmadog. He rose to dominate British politics, and to direct the affairs of the most expansive empire the world had known, seeing off thousands of more privileged rivals, on the basis of truly exceptional native gifts, and without even speaking English as his first language.

How he got into the position to direct World War I is one of the most remarkable personal trajectories in British history. Contemporaries everywhere saw it as an astonishing story, even in the most advanced democracies. As the New York Times asked when Lloyd George visited America in 1923, “Was there ever a more romantic rise from the humblest beginning than this?”

The second reason why Lloyd George is fascinating is his extraordinary command of words. Collins is good on this. The book is full of speeches that turn tides and smash competitors. Lloyd George could exercise an equally mesmeric command over both the Commons and mass audiences, typically rather different skills. Harold Macmillan called him “the best parliamentary debater of his, or perhaps any, day”.

Biblical references and Welsh valleys suffused his speeches. As another American journalist put it, when Lloyd George was speaking, “none approaches him in witchery of word or wealth of imagery”, with his “almost flawless phraseology” communicated through a voice “like a silver bell that vibrates with emotion”. Leading an imperial democracy through a global war demanded rhetorical powers of the rarest kind. Asquith lacked them. That, amongst other reasons, is why Lloyd George was able to shunt him aside.

The last reason we should all be interested in Lloyd George — as readers will have anticipated — is that he was the last British politician to inter a governing party. His actions during the war split the Liberals into Pro-Asquith and pro-Lloyd George factions, and the government he led from 1916 until 1922 was propped up by the Conservatives. Though the Liberal split was partly healed in 1923, it was all over for the party as a governing force. By the time Lloyd George at last became leader of the Liberal Party (in the Commons) in 1924, he had only a rump of 40 MPs left to command.

By the 1920s, Lloyd George’s shifting ideologies could not easily accommodate the old party traditions or the new forces reshaping allegiances and identities in the aftermath of the war. In 1918 he described his political creed to George Riddell, the press magnate, as “Nationalist-Socialist”. The consequence was an unprecedented redrawing of the map of British party politics, producing the Labour/Conservative hegemony we have lived with ever since.

The rot had arguably begun to set in for the Liberals in the elections of 1910, when they lost their majority. Fourteen years later, in 1924, Lloyd George stepped up to the Commons leadership of an exhausted, defeated party, and neither he nor his successors could arrest the slide into irrelevance. […] The Liberals could not come back because they were left with no clothes of their own. What had once been distinctive lines on economics, religion, welfare, the constitution, foreign policy and even “progress” were either appropriated by their competitors or ceased to be politically relevant. The party’s history as the dominant political force of the last near-century was no proof against radical structural change.

Alex Middleton, “Snapshot of the PM who killed his party”, The Critic, 2024-08-01.

November 7, 2024

Forgotten War Ep4 – Rise of the Chindits

HardThrasher

Published 4 Nov 2024Please consider donations of any size to the Burma Star Memorial Fund who aim to ensure remembrance of those who fought with, in and against 14th Army 1941–1945 — https://burmastarmemorial.org/

(more…)

November 4, 2024

Cicero 101: Life, Death & Legacy

MoAn Inc.

Published 31 Oct 2024A Bit About MoAn Inc. — Trust me, the ancient world isn’t as boring as you may think. In this series, I’ll talk you through all things Cicero. I hope you guys enjoy this wonderful book as much as all us nerds do.

(more…)

October 1, 2024

QotD: Napoleon Bonaparte and Tsar Alexander I

Jane: … The most affecting episode in the whole book [Napoleon the Great by Andrew Roberts], to my mind — even more than his slow rotting away on St. Helena — is Napoleon’s conferences with Alexander I at Tilsit. Here are these two emperors meeting on their glorious raft in the middle of the river, with poor Frederick William of Prussia banished from the cool kids’ table, and Napoleon thinks he’s found a peer, a kindred soul, they’re going to stay up all night talking about greatness and leadership and literature … And the whole time the Tsar is silently fuming at the audacity of this upstart and biding his time until he can crush him. The whole buildup to the invasion has a horror movie quality to it — no, don’t go investigate that noise, just get out of

the houseRussia! — but even without knowing how horribly that turns out, you feel sorry for the guy. Napoleon thinks they have something important in common, and Alexander thinks Napoleon’s very existence is the enemy of the entire old world of authority and tradition and monarchy that he represents.Good thing the Russian Empire never gets decadent and unknowingly harbors the seeds of its own destruction!

John: Yeah, I think you’ve got the correct two finalists, but there’s one episode in particular on St. Helena that edges out his time bro-ing out with Tsar Alexander on the raft. It’s the supremely unlikely scene where old, beaten, obese, dying Napoleon strikes up a bizarre friendship with a young English girl. It all begins when she trolls him successfully over his army freezing to death in the smoldering ruins of Moscow, and after a moment of anger he takes an instant liking to her and starts pouring out his heart to her, teaching her all he knows about military strategy, and playing games in her parents’ yard where the two of them pretend to conquer Europe. Call me weird, but I think this above all really showcases Napoleon’s greatness of soul. That little girl later published her memoirs, btw, and I really want to read them someday.

Jane and John Psmith, “JOINT REVIEW: Napoleon the Great, by Andrew Roberts”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-01-21.

September 30, 2024

Sulla, civil war, and dictatorship

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published Jun 5, 2024The latest instalment of the Conquered and the Proud looks at the first few decades of the first century BC. We deal with the final days of Marius, the rise of Sulla, the escalating spiral of civil wars and massacres as Rome’s traditional political system starts breaking down.

Primary Sources – Plutarch, Marius, Sulla, Pompey, Crassus, Cicero and Caesar. Appian Civil Wars and Mithridatic Wars.

Secondary (a small selection) –

P. Brunt, Social Conflicts in the Roman Republic & The Fall of The Roman Republic

A. Keaveney, Sulla – the last Republican

R. Seager, Pompey the Great: A political Biography

September 27, 2024

QotD: Nietzsche – a gamma male incel?

Nietzsche seems to elicit either frothing anger or dismissive contempt amongst Christians. This is understandable. He did after all write a book called The Antichrist, and coined such memorable phrases as “God is dead”. Characterizing Christianity as a form of slave morality doesn’t endear him to Christians either. As to the contemptuous dismissal, this is usually phrased along the lines that Nietzsche spent the last decade of his life as a catatonic madman, probably due to advanced syphilis, and that his life before this was marked by professional and social failure, continuous health problems such as severe migraines and painful digestive issues, and rejection by romantic interests. This “Ubermensch“, they say, was a loser. He was an incel. He was a gamma male.

If you aren’t familiar with Vox Day’s sociosexual hierarchy [SSH], you can find the definition of its categories at his Sigma Game Substack here. Briefly, the SSH classifies men (and only men) according to the ways they relate to one another, and therefore (since women are exquisitely socially sensitive), to women. It divides men into the following categories: alphas, the natural leaders who get most of the female attention; betas or bravos, who are not Pyjama Boy, but rather the alpha’s lieutenants and capos, enforcing the alpha’s rule and getting some of the female attention that spills out of his penumbra; gammas, who are essentially low-t nerds with poor social skills that scare the hoes; deltas, who are basically the workers, the ordinary joes who keep everything running, and are sometimes after much struggle successful in landing a waifu; omegas, who are at the bottom of the hierarchy, neither receiving much from it nor contributing anything to it, and never leave their dirty basements; sigmas, who are essentially lone wolves with an ambivalent relationship to the hierarchy, which they don’t really care about (they have their own, more interesting thing they’re doing, which they’re happy to do alone if necessary), but nevertheless do quite well within it, often challenging the alpha’s authority without intending to; and lambdas, who exist outside of the sociosexual hierarchy because they are literally gay.

If you want an image of the SSH, consider your typical American high-school in the 1980s. The alpha is the captain of the football team; the betas are the other football team players; the gammas are the chess club nerds; the deltas are the normal kids with nothing much remarkable about them; the sigma is the kid in the metal shirt who cuts class because it bores him and then shows up at the party with a hot girl from a different school that no one has met before; the omegas are the dropout welfare trash kids; and the lambdas are the theatre kids.

So, was Nietzsche a gamma male incel? Was he a loser and a nerd?

Of course he was. Vox is absolutely correct about this.

Christians will usually follow up the gamma male incel attack by noting the absurd contrast between Nietzsche’s lived reality, as a frail neurasthenic with a terminal case of oneitis who could be sent into days of migraines by a chance encounter with a caffeinated beverage, and the concept of the Ubermensch he preached in his writings, most notably in his very strange novel? prose poem? mental breakdown? Thus Spake Zarathustra. By the same token we might note that Virgil was no Aeneas. The character created by the artist is not the artist; if the artist was the character, he’d be too busy running around doing heroic character things, not hunched over in his scriptorium scribbling away with ink-stained fingers.

And make no mistake about it – Nietzsche was as much the poet as the philosopher, indeed, probably more poet than philosopher. One of the most common complaints you’ll hear about Nietzsche is that it’s not at all clear, much of the time, what he’s getting at. What is the actual argument here? people will ask. They’re used to philosophers whose turgid prose is a loose string of logical syllogisms, composed with all the charm of a mathematical derivation. The wild electricity of Nietzsche’s divine madness is an entirely different genre.

We call Nietzsche a philosopher because that’s the closest category we have to throw him in, but this is a poor categorization. Nietzsche’s mind – and yes, this may well be because it was broken by syphilis – did not proceed according to the narrow rails enforced by a rigid adherence to logic and reason. It was not weighed down by the gravity of methodological rigour. That is not to say that he did not apply reason, simply that he was not limited to it. He made use of revelation, of inspiration, just as much. He felt as much as he thought when he wrote, inhabiting the ideas he developed with his passion as much as his intellect. He thought with his whole brain, using both his left hemisphere and his right – in Nietzsche’s language, the Apollonian and the Dionysian. Being aware that philosophy specifically, and Western thought more generally, was to an extraordinary and even pathological degree locked into the left-hemisphere mode, into the Apollonian realm of rational dialectic, he went out of his way to cultivate the Dionysian instead, to get into touch with his intuitive, subconscious, “irrational” mind. As much as Nietzsche was a philosopher, he was also an artist, a poet1, a mystic, and even, dare I say it, a prophet.

None of which is to say that he was not also a giant loser.

But then, most philosophers are nerds who are bad with the ladies. There are exceptions, of course. There is no record of Plato being bad with the ladies; Plato’s tastes are reputed to have run in different directions.

John Carter, “The Prophet of the Twentieth Century”, Postcards from Barsoom, 2024-06-25.

1. He published a volume of actual poetry, which wasn’t very good; he also dabbled in musical composition, which was even worse.

September 25, 2024

The Life and Times of Xerxes

seangabb

Published Jun 10, 2024An occasional lecture for our Classics Week, this was given to provide historical background for a lecture from the Music Department on Handel’s opera “Serse” (1738).

Books by Sean Gabb: https://www.amazon.co.uk/kindle-dbs/e…

His historical novels (under the pen name “Richard Blake”): https://www.amazon.co.uk/Richard-Blak…

If you have enjoyed this lecture, its author might enjoy a bag of coffee, or some other small token of esteem: https://www.amazon.co.uk/hz/wishlist/…

September 23, 2024

Forgotten War Ep3 – Death in the Arakan

HardThrasher

Published 18 Sept 2024Please consider donations of any size to the Burma Star Memorial Fund who aim to ensure remembrance of those who fought with, in and against 14th Army 1941–1945 — https://burmastarmemorial.org/

(more…)

September 22, 2024

History and story in HBO’s Rome – S1E1 “The Lost Eagle”

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published Jun 12, 2024Starting a series looking at the HBO/BBC co production drama series ROME. We will look at how they chose to tell the story, at what they changed and where they stuck closer to the history.