Wood, even when dried, contains quite a bit of water and volatile compounds; the former slows the rate of combustion and absorbs the energy, while the latter combusts incompletely, throwing off soot and smoke which contains carbon which would burn, if it had still been in the fire. All of that limits the burning temperature of wood; common woods often burn at most around 800-900°C, which isn’t enough for the tasks we are going to put it to.

Charcoaling solves this problem. By heating the wood in conditions where there isn’t enough air for it to actually ignite and burn, the water is all boiled off and the remaining solid material reduced to lumps of pure carbon, which will burn much hotter (in excess of 1,150°C, which is the target for a bloomery). Moreover, as more or less pure carbon lumps, the charcoal doesn’t have bunches of impurities which might foul our iron (like the sulfur common in mineral coal).

That said, this is a tricky process. The wood needs to be heated around 300-350°C, well above its ignition temperature, but mostly kept from actually burning by lack of oxygen (if you let oxygen in, the wood is going to burn away all of its carbon to CO2, which will, among other things, cause you to miss your emissions target and also remove all of the carbon you need to actually have charcoal), which in practice means the pile needs some oxygen to maintain enough combustion to keep the heat correct, but not so much that it bursts into flame, nor so little that it is totally extinguished. The method for doing this changed little from the ancient world to the medieval period; the systems described by Pliny (NH 16.8.23) and Theophrastus (HP 5.9.4) is the same method we see used in the early modern period.

First, the wood is cut and sawn into logs of fairly moderate size. Branches are removed; the logs need to be straight and smooth because they need to be packed very densely. They are then assembled into a conical pile, with a hollow center shaft; the pile is sometimes dug down into the ground, sometimes assembled at ground-level (as a fun quirk of the ancient evidence, the Latin-language sources generally think of above-ground charcoaling, whereas the Greek-language sources tend to assume a shallow pit is used). The wood pile is then covered in a clay structure referred to a charcoal kiln; this is not a permanent structure, but is instead reconstructed for each charcoal burning. Finally, the hollow center is filled with brushwood or wood-chips to provide the fuel for the actual combustion; this fuel is lit and the shaft almost entirely sealed by an air-tight layer of earth.

The fuel ignites and begins consuming the oxygen from the interior of the kiln, both heating the wood but also stealing the oxygen the wood needs to combust itself. The charcoal burner (often called collier, before that term meant “coal miner” it meant “charcoal burner”) manages the charcoal pile through the process by watching the smoke it emits and using its color to gauge the level of combustion (dark, sooty smoke would indicate that the process wasn’t yet done, while white smoke meant that the combustion was now happening “clean” indicating that the carbonization was finished). The burner can then influence the process by either puncturing or sealing holes in the kiln to increase or decrease airflow, working to achieve a balance where there is just enough oxygen to keep the fuel burning, but not enough that the wood catches fire in earnest. A decent sized kiln typically took about six to eight days to complete the carbonization process. Once it cooled, the kiln could be broken open and the pile of effectively pure carbon extracted.

Raw charcoal generally has to be made fairly close to the point of use, because the mass of carbon is so friable that it is difficult to transport it very far. Modern charcoal (like the cooking charcoal one may get for a grill) is pressed into briquettes using binders, originally using wet clay and later tar or pitch, to make compact, non-friable bricks. This kind of packing seems to have originated with coal-mining; I can find no evidence of its use in the ancient or medieval period with charcoal. As a result, smelting operations, which require truly prodigious amounts of charcoal, had to take place near supplies of wood; Sim and Ridge (op cit.) note that transport beyond 5-6km would degrade the charcoal so badly as to make it worthless; distances below 4km seem to have been more typical. Moving the pre-burned wood was also undesirable because so much material was lost in the charcoaling process, making moving green wood grossly inefficient. Consequently, for instance, we know that when Roman iron-working operations on Elba exhausted the wood supplies there, the iron ore was moved by ship to Populonia, on the coast of Italy to be smelted closer to the wood supply.

It is worth getting a sense of the overall efficiency of this process. Modern charcoaling is more efficient and can often get yields (that is, the mass of the charcoal when compared to the mass of the wood) as high as 40%, but ancient and medieval charcoaling was far less efficient. Sim and Ridge (op cit.) note ratios of initial-mass to the final charcoal ranging from 4:1 to 12:1 (or 25% to 8.3% efficiency), with 7:1 being a typical average (14%).

We can actually get a sense of the labor intensity of this job. Sim and Ridge (op cit.) note that a skilled wood-cutter can cut about a cord of wood in a day, in optimal conditions; a cord is a volume measure, but most woods mass around 4,000lbs (1,814kg) per cord. Constructing the kiln and moving the wood is also likely to take time and while more than one charcoal kiln can be running at once, the operator has to stay with them (and thus cannot be cutting any wood, though a larger operation with multiple assistants might). A single-man operation thus might need 8-10 days to charcoal a cord of wood, which would in turn produce something like 560lbs (253.96kg) of charcoal. A larger operation which has both dedicated wood-cutters and colliers running multiple kilns might be able to cut the man-days-per-cord down to something like 3 or 4, potentially doubling or tripling output (but requiring a number more workers). In short, by and large our sources suggest this was a fairly labor intensive job in order to produce sufficient amounts of charcoal for iron production of any scale.

Bret Devereaux, “Iron, How Did They Make It? Part II, Trees for Blooms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-09-25.

October 10, 2023

October 8, 2023

October 6, 2023

Farnborough Airshow – 1959 (in colour)

spottydog4477

Published 28 Dec 2009Farnborough Airshow – 1959 (in colour)

October 5, 2023

The Soviet Spies who Kickstarted the Nuclear Arms Race

World War Two

Published 4 Oct 2023Last episode we saw Klaus Fuchs steal details of the American atomic bomb for the Soviet Union. But he’s only one component of a much bigger conspiracy. Today, Astrid introduces you to the mysterious web of Soviet atomic spies. Their work changed our world forever.

(more…)

October 2, 2023

Why Web Filters Don’t Work: Penistone and the Scunthorpe Problem

Tom Scott

Published 6 Jun 2016In a small town with an unfortunate name, let’s talk about filtering and innuendo. And use it as an excuse for as many visual jokes as possible.

(more…)

September 29, 2023

WW2 Jet Engine Development

World War Two

Published 28 Sep 2023Jet planes and jet engine technology revolutionized air travel, as we are all well aware. However, the development of jet planes during WW2 was fraught with all sorts of obstacles and hurdles. Let’s take a look at it.

(more…)

September 27, 2023

QotD: Geeks and hackers

One of the interesting things about being a participant-observer anthropologist, as I am, is that you often develop implicit knowledge that doesn’t become explicit until someone challenges you on it. The seed of this post was on a recent comment thread where I was challenged to specify the difference between a geek and a hacker. And I found that I knew the answer. Geeks are consumers of culture; hackers are producers.

Thus, one doesn’t expect a “gaming geek” or a “computer geek” or a “physics geek” to actually produce games or software or original physics – but a “computer hacker” is expected to produce software, or (less commonly) hardware customizations or homebrewing. I cannot attest to the use of the terms “gaming hacker” or “physics hacker”, but I am as certain as of what I had for breakfast that computer hackers would expect a person so labeled to originate games or physics rather than merely being a connoisseur of such things.

One thing that makes this distinction interesting is that it’s a recently-evolved one. When I first edited the Jargon File in 1990, “geek” was just beginning a long march towards respectability. It’s from a Germanic root meaning “fool” or “idiot” and for a long time was associated with the sort of carnival freak-show performer who bit the heads off chickens. Over the next ten years it became steadily more widely and positively self-applied by people with “non-mainstream” interests, especially those centered around computers or gaming or science fiction. From the self-application of “geek” by those people it spread to elsewhere in science and engineering, and now even more widely; my wife the attorney and costume historian now uses the terms “law geek” and “costume geek” and is understood by her peers, but it would have been quite unlikely and a faux pas for her to have done that before the last few years.

Because I remembered the pre-1990 history, I resisted calling myself a “geek” for a long time, but I stopped around 2005-2006 – after most other techies, but before it became a term my wife’s non-techie peers used politely. The sting has been drawn from the word. And it’s useful when I want to emphasize what I have in common with have in common with other geeks, rather than pointing at the more restricted category of “hacker”. All hackers are, almost by definition, geeks – but the reverse is not true.

The word “hacker”, of course, has long been something of a cultural football. Part of the rise of “geek” in the 1990s was probably due to hackers deciding they couldn’t fight journalistic corruption of the term to refer to computer criminals – crackers. But the tremendous growth and increase in prestige of the hacker culture since 1997, consequent on the success of the open-source movement, has given the hackers a stronger position from which to assert and reclaim that label from abuse than they had before. I track this from the reactions I get when I explain it to journalists – rather more positive, and much more willing to accept a hacker-lexicographer’s authority to pronounce on the matter, than in the early to mid-1990s when I was first doing that gig.

Eric S. Raymond, “Geeks, hackers, nerds, and crackers: on language boundaries”, Armed and Dangerous, 2011-01-09.

September 25, 2023

September 21, 2023

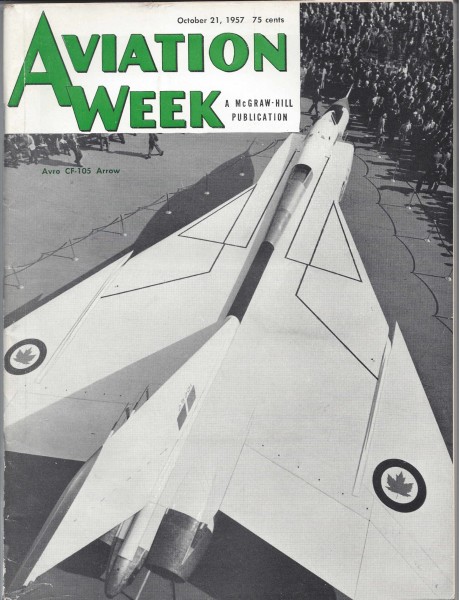

A new paper on the cancellation of the Avro Arrow in 1959

The National Post republished a Canadian Press article about a new research paper by Alan Barnes in the Canadian Military History journal:

In the years after the Second World War, Canada developed its ability to prepare strategic intelligence assessments on defence and foreign policy, the paper notes. It would no longer have to rely entirely on assessments from the United States and Britain.

The analytic capability allowed Canada to fully participate in preparing the assessments on the Soviet threat to North America that would underpin joint Canada-U.S. planning for continental defence, Barnes notes.

“The CF-100 Canuck, a jet interceptor developed and manufactured in Canada, was just entering service, but there were already concerns that it might soon be outclassed by newer Soviet bombers operating at higher altitudes and faster speeds.”

In November 1952, the Royal Canadian Air Force called for an aircraft with a speed of Mach 2 and the ability to fly at 50,000 feet. “These demanding specifications contributed to the escalating costs and frequent delays in the CF-105 program.”

The Soviets would soon display a new long-range jet bomber, the Bison, at the 1954 May Day parade in Moscow. At an airshow the following year, a fly-past of 28 Bison seemed to indicate that the bomber had entered serial production, two years earlier than predicted, the paper says. In fact, only 18 prototype aircraft participated in the airshow, flying past several times to give the impression of larger numbers.

Even so, this display, along with the appearance of a new Soviet long-range turboprop bomber, the Tu-95 (dubbed the Bear), raised fears that the Soviet Union would soon outnumber the United States in intercontinental bombers, sparking a “Bomber Gap” controversy that figured prominently in American politics, the paper says.

[…]

A January 1958 assessment, “The Threat to North America, 1958-1967”, by Canada’s Joint Intelligence Committee, a co-ordinating body, ultimately had the greatest impact on decisions related to the Arrow, the paper says.

The assessment laid out clear judgments concerning the imminent transition from crewed bombers to ballistic missiles and described the limited size and capabilities of the Soviet bomber force, Barnes notes.

It observed that the Soviet ballistic missiles which were on the verge of being developed were likely to be markedly superior to the foreseeable defences, and concluded that missiles would progressively replace aircraft as the main threat to North America.

The assessment said this meant there would be little justification for the Soviet Union to increase the number of bombers, or to introduce new ones, after 1960.

“The (Joint Intelligence Committee)’s January 1958 assessment was correct in foreseeing Moscow’s shift from bombers to missiles over the subsequent decade,” Barnes writes.

He points out that following the Sputnik launch, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev came to see missiles as a panacea for a range of defence problems and as a cheaper alternative to conventional weapons. “With the Soviet bomber force now looking irrelevant and obsolete, it was relegated to a secondary position in Soviet military thinking.”

September 20, 2023

Wire Guided Tank Killer | Swingfire | Anti-Tank Chats

The Tank Museum

Published 2 Jun 2023In this video, Chris Copson looks at the Swingfire, a Cold War period anti-tank guided weapons system. This powerful and hard-hitting missile was mounted on vehicles including Striker, Ferret, and FV 432. With a range of up to 4km, it had the significant advantage that it would outrange tank guns and could be fired remotely by the controller, enabling the launch vehicle to remain in cover.

(more…)

September 17, 2023

September 16, 2023

QotD: The Persian “Royal Roads”

The first thing worth clearing up about the Roman roads is that, contrary to a lot of popular belief, the Roman roads were not the first of their kind. And I mean that in a variety of ways: the construction of roadways with a solid, impermeable surface (that is, not just clearing and packing dirt) was not new with the Romans, but more importantly the concept of knitting together an empire with a system of roadways was not new.

The oldest road network that we have pretty good evidence for was the Persian Royal Road of the Achaemenids but these too were not the first (the Achaemenid dynasty ruling a vast empire from 559 to 330 BC; this is the Persian Empire of Xerxes and Darius III). Even before them the Assyrians (Middle and Neo-Assyrian Empires running from 1363 to 609 BC)1 had build roadways to hold together parts of their empire, though I confess I know very little of the extent of that road system except that we’re fairly sure it existed and like the later systems we’re going to talk about, it included not just the physical infrastructure of the roads but a sophisticated relay system to allow official messengers to move very rapidly over the network.

The modern perception of the Persian Royal Road is conditioned perhaps a bit too much by Herodotus who described the royal road – singular – as a single highway running from Susa to Sardis. Susa was one of several Achaemenid royal capitals and it sat at the edge of the Iranian plateau where it meets the lowland valley of Mesopotamia, essentially sitting right on the edge where the Persian “heartland” met the area of imperial conquests. Meanwhile, Sardis was the westernmost major Achaemenid administrative center, the regional capital, as it were, for Anatolia and the Aegean. So you can see the logic of that being an important route, but the road system was much larger. Indeed, here is a very rough sketch of how we might understand the whole system.

Compare the dashed line – the Royal Road as described by Herodotus – with the solid lines, the rest of the system we can glean from other sources or from archaeology and you can see that Herodotus hasn’t given us the whole story. For what it is worth, I don’t think Herodotus here is trying to lie – he has just described the largest and most important trunk road that leads to his part of the world.

This system doubtlessly emerged over time. Substantial parts of the road network almost certainly predated the Achaemenids and at least some elements were in place under the first two Achaemenid Great Kings (Cyrus II, r. 559-530 and Cambyses II, r. 530-22) but it seems clear that it is the third Achaemenid ruler, Darius I (r. 522-486; this is the fellow who dispatched the expedition defeated at Marathon, but his reign was far more important than that – he is the great organizer of the Persian Empire) who was responsible for the organization, formalization and expansion of the system. And in practice we can split that system into two parts, the physical infrastructure of roads and then the relay system built atop that system.

In terms of the physical infrastructure, as far as I can tell, the quality of Persian Royal Roads varied a lot. In some areas where the terrain was difficult, we see sections of road cut into the rock or built via causeways over ravines. Some areas were paved, but most – even most of the “royal” roads (as distinct from ancillary travel routes) were not.2 That said, maintenance seems to have been more regular on the royal roads, meaning they would be restored more rapidly after things like heavy rains that might wash an unpaved road out, making them more reliable transport routes for everyone. They also seem to have been quite a bit wider; Achaemenid armies could have long logistics tails and these roads had to accommodate those. Several excavated sections of royal roads are around 5m wide, but we ought to expect a lot of variation.

On top of the physical infrastructure, there was also a system of way-stations and stopover points along the road. These were not amenities for everyone but rather a system for moving state officials, messengers, soldiers, and property (like taxes). While anyone could, presumably, walk down the road, official travelers carried a sealed travel authorization issued by either a satrap (the Persian provincial governors) or the king himself. Such authorizations declared how many travelers there were, where they were going and what the way-stations, which stocked supplies, should give them. Of course that in turn meant that local satraps had to make sure that way-stations remained stocked up with food, fodder for animals, spare horses and so on. Fast messengers could also be sent who, with that same authorization, would change horses at each way-station, allowing them to move extremely fast over the system, with one estimate suggesting that a crucial message could make the trip from Sardis to Susa – a trip of approximately 2,500km (1,550 miles, give or take) in twelve days (by exchanging not only horses, but riders, as it moved).

All of which gives some pretty important clues to why royal roads were set up and maintained. Notice how the system specifically links together key administrative hubs, like the three main Achaemenid capitals (Susa, Ekbatana and Persepolis) and key administrative centers (Memphis, Sardis, Babylon, etc.) and that while anyone can use the roads, the roads serve as the basis for a system to handle the logistics of moving officials and state messages, which of course could also serve as the basis for moving armies. After all, you can send messengers down the royal roads, through the existing system set up for them, to instruct your satraps to gather local forces or more importantly to gather local food supplies and move them to the road in depots where the army can pick them up (and perhaps some local troops) as it moves through to a nearby trouble spot (while the nice, wide road allows you to bring lots of pack animals and carts with your army).

In short this is a large, expensive but effective system for managing the problem of distance in a large empire. Cutting down travel and message times reduces the independence of the satraps, allowing the Great King to keep an eye on them, while the roads provide the means to swiftly move armies from the core of the empire out to the periphery. We can actually see this play out with Alexander’s invasion. He crosses into Asia in 334 and defeats the local satrapal army at Granicus in 334. Moving into the Levant in 333, he’s met at Issus by Darius III with a massive army, collected from the central and western parts of the empire – which means that news of Alexander’s coming has reached Darius who has then marshaled all of those troops from his satrapies (and hired some mercenaries), presumably using his efficient message system to do it and then moved that force down the road system to meet Alexander. Alexander defeats that army, but is met by another huge army at Gaugamela in 331, this time gathered mostly from the eastern parts of the empire. While the Persian army fails in defeating Alexander, the exercise shows the power of the system in allowing the Great King, Darius III to coordinate the military efforts of an enormous empire.

So this is a system meant to enable the imperial center to control its periphery by enabling the court to keep tabs on the satraps, to get messages to and from them and move armies and officials (and taxes!) around. And doubtless it was also not lost on anyone that such a visible series of public works – even if the roads were not always paved and had to be repaired after heavy rains and such – was also an exercise in legitimacy building, both a visual demonstration of the Great King’s power and resources but also a display of his generosity and industry.

And I lead with all of that because the Roman road network works the same way, just on an even larger scale. Which isn’t to say the Romans were copying the Achaemenids (they don’t seem to have been) but rather that this is a common response to the problem of managing an uncommonly large empire.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Roman Roads”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-06-02.

1. The Middle Assyrian Empire and the Neo-Assyrian or New Assyrian Empires were, in fact, the same state. We split them up because of a severe contraction in Assyrian power during the Late Bronze Age Collapse.

2. On this, see Henkelman and Jacobs, 727-8

September 14, 2023

Scott Alexander reviews the (old) Elon Musk biography

It’s okay, he makes it clear from the start that he’s talking about Ashlee Vance’s earlier work, not the one that just hit the shelves this year:

This isn’t the new Musk biography everyone’s talking about. This is the 2015 Musk biography by Ashlee Vance. I started reading it in July, before I knew there was a new one. It’s fine: Musk never changes. He’s always been exactly the same person he is now.1

I read the book to try to figure out who that was. Musk is a paradox. He spearheaded the creation of the world’s most advanced rockets, which suggests that he is smart. He’s the richest man on Earth, which suggests that he makes good business decisions. But we constantly see this smart, good-business-decision-making person make seemingly stupid business decisions. He picks unnecessary fights with regulators. Files junk lawsuits he can’t possibly win. Abuses indispensable employees. Renames one of the most recognizable brands ever.

Musk creates cognitive dissonance: how can someone be so smart and so dumb at the same time? To reduce the dissonance, people have spawned a whole industry of Musk-bashing, trying to explain away each of his accomplishments: Peter Thiel gets all the credit for PayPal, Martin Eberhard gets all the credit for Tesla, NASA cash keeps SpaceX afloat, something something blood emeralds. Others try to come up with reasons he’s wholly smart – a 4D chessmaster whose apparent drunken stumbles lead inexorably to victory.

Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, And The Quest For A Fantastic Future delights in its refusal to resolve the dissonance. Musk has always been exactly the same person he is now, and exactly what he looks like. He is without deception, without subtlety, without unexpected depths.

The main answer to the paradox of “how does he succeed while making so many bad decisions?” is that he’s the most focused person in the world. When he decides to do something, he comes up with an absurdly optimistic timeline for how quickly it can happen if everything goes as well as the laws of physics allow. He – I think the book provides ample evidence for this – genuinely believes this timeline,2 or at least half-believingly wills for it to be true. Then, when things go less quickly than that, it’s like red-hot knives stabbing his brain. He gets obsessed, screams at everyone involved, puts in twenty hour days for months on end trying to try to get the project “back on track”. He comes up with absurd shortcuts nobody else would ever consider, trying to win back a few days or weeks. If a specific person stands in his way, he fires that person (if they are an employee), unleashes nonstop verbal abuse on them3 (if they will listen) or sues them (if they’re anyone else). The end result never quite reaches the original goal, but still happens faster than anyone except Elon thought possible. A Tesla employee described his style as demanding a car go from LA to NYC on a single charge, which is impossible, but he puts in such a strong effort that the car makes it to New Mexico.

This is the Musk Strategy For Business Success; the rest is just commentary.

1. Vance starts with the story of the biography itself. When Musk learned he was being profiled, he called Vance, threatened that he could “make [his] life very difficult”, and demanded the right to include footnotes wherever he wanted telling his side of the story. When Vance said that wasn’t how things worked, Elon invited him to dinner to talk about it. Elon arrived late, and spent the first few courses talking about the risk of artificial superintelligence. When Vance tried to redirect the conversation to the biography, Elon abruptly agreed, gave him unprecedented access to everyone, and won him over so thoroughly that the book ends with a prediction that Musk will succeed at everything and become the richest man in the world (a bold claim back in 2015).

I like this story but find myself dwelling on Musk’s request — why shouldn’t he be allowed to read his own biography before publication and include footnotes giving his side of the story where he disagrees? That sounds like it should be standard practice! If I ever write a post about any of you and you disagree with it, feel free to ask me to add a footnote giving your side of the story (or realistically I’ll put it in an Open Thread).

2. The book gives several examples of times Musk almost went bankrupt by underestimating how long a project would take, then got saved by an amazing stroke of luck at the last second. When Vance asked him about his original plan to get the Falcon 1 done in a year, he said:

“Reminded about the initial 2003 target date to fly the Falcon 1, Musk acted shocked. ‘Are you serious?’ he said. ‘We said that? Okay, that’s ridiculous. I think I just didn’t know what the hell I was talking about. The only thing I had prior experience in was software, and, yeah, you can write a bunch of software and launch a website in a year. No problem. This isn’t like software. It doesn’t work that way with rockets.”

But also, the employees who Vance interviewed admit that whenever Musk asks how long something will take, they give him a super-optimistic timeline, because otherwise he will yell at them.

3. I wondered whether Elon was self-aware. The answer seems to be yes. Here’s an email he wrote a friend:

“I am by nature obsessive compulsive. In terms of being an asshole or screwing up, I’m personally as guilty of that as anyone, and am somewhat thick-skinned in this regard due to large amounts of scar tissue. What matters to me is winning, and not in a small way. God knows why … it’s probably [rooted] in some very disturbing psychoanalytical black hole or neural short circuit.”

September 13, 2023

Why Do People In Old Movies Talk Weird?

BrainStuff – HowStuffWorks

Published 25 Nov 2014It’s not quite British, and it’s not quite American – so what gives? Why do all those actors of yesteryear have such a distinct and strange accent?

If you’ve ever heard old movies or newsreels from the thirties or forties, then you’ve probably heard that weird old-timey voice.

It sounds a little like a blend between American English and a form of British English. So what is this cadence, exactly?

This type of pronunciation is called the Transatlantic, or Mid-Atlantic, accent. And it isn’t like most other accents – instead of naturally evolving, the Transatlantic accent was acquired. This means that people in the United States were taught to speak in this voice. Historically Transatlantic speech was the hallmark of aristocratic America and theatre. In upper-class boarding schools across New England, students learned the Transatlantic accent as an international norm for communication, similar to the way posh British society used Received Pronunciation – essentially, the way the Queen and aristocrats are taught to speak.

It has several quasi-British elements, such a lack of rhoticity. This means that Mid-Atlantic speakers dropped their “r’s” at the end of words like “winner” or “clear”. They’ll also use softer, British vowels – “dahnce” instead of “dance”, for instance. Another thing that stands out is the emphasis on clipped, sharp t’s. In American English we often pronounce the “t” in words like “writer” and “water” as d’s. Transatlantic speakers will hit that T like it stole something. “Writer”. “Water”.

But, again, this speech pattern isn’t completely British, nor completely American. Instead, it’s a form of English that’s hard to place … and that’s part of why Hollywood loved it.

There’s also a theory that technological constraints helped Mid-Atlantic’s popularity. According to Professor Jay O’Berski, this nasally, clipped pronunciation is a vestige from the early days of radio. Receivers had very little bass technology at the time, and it was very difficult – if not impossible – to hear bass tones on your home device. Now we live in an age where bass technology booms from the trunks of cars across America.

So what happened to this accent? Linguist William Labov notes that Mid-Atlantic speech fell out of favor after World War II, as fewer teachers continued teaching the pronunciation to their students. That’s one of the reasons this speech sounds so “old-timey” to us today: when people learn it, they’re usually learning it for acting purposes, rather than for everyday use. However, we can still hear the effects of Mid-Atlantic speech in recordings of everyone from Katherine Hepburn to Franklin D. Roosevelt and, of course, countless films, newsreels and radio shows from the 30s and 40s.

(more…)