Consider the history of canned food. It has obvious military applications — Napoleon famously quipped that an army marches on its stomach, and as canning was largely invented in France, he made some effort to issue food to his troops (as opposed to local procurement and / or “living off the land”). He didn’t quite get there, but the resultant revolution in logistics was as important to the conduct of war, in its way, as just about anything else. If you don’t know how armies are provisioned, you’re likely to miss something when you talk about wars.

You might even miss something culturally. For instance, there’s an entire sub-subdiscipline called “Food and Foodways”, and it’s not as silly as it sounds. Canned food was an important part of British cultural life in the Raj, for instance. File it under “Women Ruin Everything” — once it got safe enough for ladies to have a reasonable chance of surviving East of Suez, the awesome freewheeling decadence of the “White Mughals” period was replaced by dour, dowdy Victorian bullshit. Every summer the “fishing fleet” pulled into Calcutta harbor, disembarking scads of ugly British girls with a Bible in one hand and a can of spotted dick in the other, determined to snag the highest-ranking ICS man they could and, in the process, turn India into another boring suburb of Edinburgh. Anglo-Indian cookbooks are full of recipes for horrid British glop straight out of cans, and if you routinely got really, really sick from eating spoiled stuff, well, hard cheese, old chap! Heaven forbid you eat the delicious, nutritious, climate-optimized cuisine that was literally right there …

If you want to argue that the Indian Army fought so many border wars just to get away from sour, hectoring memsahibs and their godawful tinned slop, I’m not going to stop you.

Anyway, the point is, IF you are conversant enough with the relevant technical stuff, it occurs to me that you can get a snapshot of embedded cultural assumptions by looking at a period’s characteristic or representative technology.

Severian, “Assumption Artifacts”, Founding Questions, 2024-04-30.

January 8, 2026

QotD: Canned food and the early days of the Raj

November 22, 2025

“Whig history”

If you’ve read any history books written before the Second World War (aside from explitly Marxist interpretations), you’ll probably recognize the worldview which, subtly or overtly, informed the stories being told (and those not mentioned). On her Substack, Mary Catelli discusses “the Whig interpretation of history”:

Among the many perils of viewpoint that lurk in your path when you read history, one of the nastiest is the Whig Interpretation of History, and its variants, and other teleological views.

The original interpretation, popular in British history writing of the 19th century, was that all of history had been aiming for the wonderfully wonderful wonder that was 19th century Britain. And if it was not quite so smooth as a train ride gliding over well-laid tracks, it was unnecessary to point out minor details.

The most disastrous effect, for the reader, is that the things of the past are described for their presumed effect on the progress toward that aim. They were not described for their actual effect on the era, or how they appeared to the people of that era (possibly more important for the fiction writer), which is what a reader using them for that era needs. Down to and including excluding vital details as unimportant.

(Obviously, “development of what they regard as progress” books are more or less resistant to this, though they can press some very odd things into the service of their thesis, and sandpaper off quite a bit of things they deem anomalies. It is when it colors works about something else — or nominally about something else — that the peril really arises.)

Plus of course any coloring the viewpoint gives them in regarding the people of the era as stepping stones toward the ideal future. In particular, the heroes and villains are assigned not for the moral character of their deeds but whether they sped history along the right path. Frequently enough, any openly and clearly stated motives by the historical figures will be breezed over for the “real” motives according to the historian’s agenda. Some quote the primary source and not even apparently noticing that it contradicts the agenda before writing as if the historical figures’ intentions matched the agenda.

H. G. Wells, in The Outline of History, gets all starry-eyed about any attempt, or success, at union between countries because he’s looking forward to the beneficent World State, regardless of how the union was imposed, and what its consequences were, and again looking with a jaundiced eye on any division regardless of how justified.

It would be easier if the issue were limited to the historians of that school, but, of course, anyone who regards history in light of a progress toward the wonderful present — or future — will have the same issues. World War I hit the original Whig interpretation quite hard, but the Marxist interpretation kept roaring along, and is not quite dead yet.

October 16, 2025

QotD: The Roman proclivity to accept changes that “go back to the way things used to be”

… for a lot of Roman reforms or other changes we just don’t have a lot of evidence for how they were presented. What we often have are descriptions of programs, proposals or ideas written decades or centuries later, when their effects were known, by writers who may be some of the few people in the ancient world who might actually know how things “used to be”.

What I will say is that the Romans were very conservative in their outlook, believing that things ought to be done according to the mos maiorum – “the customs of [our] ancestors”. The very fact that the way you say “ancestors” in Latin is maiores, “the greater ones” should tell you something about the Roman attitude towards the past. And so often real innovations in Roman governance were explained as efforts to get back to the “way things were”, but of course “the way things were” is such a broad concept that you can justify pretty radical changes in some things to restore other things to “the way they were”.

The most obvious example of this, of course, is Augustus with his PR-line of a res publica restituta, “a republic restored”. Augustus made substantial changes (even if one looked past his creation of an entire shadow-office of emperor!) to Roman governance on the justification that this was necessary to “restore” the Republic; exactly what is preserved tells you a lot about what elements of the Roman (unwritten) constitution were thought to be essential to the Republic by the people that mattered (the elites). And Augustus was hardly the first; Sulla crippled the tribunate, doubled the size of the Senate and made substantial reforms to the laws claiming that he was restoring things to the way they had been – that is, restoring the Senate to its position of prominence.

And one thing that is very clear about the Greeks and Romans generally is that they had at best a fuzzy sense of their past, often ascribing considerable antiquity to things which were not old but which stretched out of living memory. Moreover there is a general sense, pervading Greek and Latin literature that people in the past were better than people now, more virtuous, more upright, possibly even physically better. You can see this notion in authors from Hesiod to Sallust. This shouldn’t be overstressed; you also had Aristotelian/Polybian “cyclical” senses of history along with moments of present-triumphalism (Vergil, for instance, and his imperium sine fine). But still there seems to have been a broad sense of the folk system that things get worse over time and thus things must have been better in the past and thus returning to the way things were done is better. We’ve discussed this thought already where it intersects with Roman religion.

And the same time, here we run into the potential weakness of probing elite mentalités in trying to understand a society. Some Romans seem quite aware of positive change over time; Pliny the Elder and Columella are both aware of improving agricultural technology in their own day, particularly as compared to older economic writing by Cato the Elder. Polybius has no problem having the Romans twice adopt new and better ship designs during the First Punic War (though both are “just-so” stories; the ancients love “just-so” stories to explain new innovations or inventions). And sometimes Roman leaders did represent things as very much new; even Augustus combined his res publica restituta rhetoric with the idea that he was ushering in a saeculum novum, a “new age” (based on the idea of 110 year cycles in history).

So there is complexity here. The Romans most certainly did not have our strong positive associations with youth and progress. Their culture expected deference to elders and certainly didn’t expect “progress” most of the time; things, they thought, generally ought to be done as they had “always been done”. Consequently, framing things as a return to the mos maiorum or as a means to return to it was always a strong political framing and presumably many of the folks doing those things believed it. On the other hand the Romans seem well aware that some of the things they did were new and that not all of these “firsts” were bad and that some things had seemed to have gotten better or more useful since the days of their maiores. And some Romans, particularly emperors, are relatively unabashed about making dramatic breaks with tradition and precedent; Diocletian comes to mind here in particular.

Bret Devereaux, “Referenda ad Senatum: January 13, 2023: Roman Traditionalism, Ancient Dates and Imperial Spies”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-01-13.

October 13, 2025

QotD: Christian observance in the late Middle Ages

It’s hard to convey just how overwhelming spiritual life was in the late Middle Ages, but I’ll try. If you can find a copy for cheap (or have access to a university library), browse around a bit in Eamon Duffy’s The Stripping of the Altars. I can’t recommend it wholeheartedly, not least because I never managed to finish it myself — it’s dense. This is not because Duffy is a bad writer or meager scholar. He’s a titan in his field, and his prose is pretty engaging (as far as academic writing goes). It’s just that the world he describes is mind numbing.

Everything is bound by ritual. Hardly a day goes by without a formal religious ceremony happening — over and above daily mass, that is — and even when there isn’t, folk rituals fill the day. Communal life is almost entirely religious. Not just in the lay brotherhoods and sisterhoods that are literally everywhere — every settlement of any size has at least one — but in the sense that the Church, as a corporate entity, owns something like 30-50% of all the land. In a world where feudal obligations are very real, having a monastery in the vicinity shapes your entire life.

And the folk rituals! The cult of the saints, for instance — reformers, both Lutheran and Erasmian, deride it as crudely mechanical. There’s St. Apollonia for toothache (she had her teeth pulled out as part of her martyrdom); St. Anthony for skin rashes; St. Guinefort, who was a dog (no, really), and so on. The reformers called all of this gross superstition, and it takes a far more subtle theologian than me to say they’re wrong. But the point is, they were there — so much so that hardly any life activity didn’t have its little ritual, its own saint.

And yet, as suffused with religion as daily life was, the Church — the corporate entity — was unimaginably remote, and unfathomably corrupt. Your local point of contact with the edifice was of course your priest, who was usually a political appointee (second sons went into the Church), and, well … you know. They probably weren’t all as bad as Chaucer et al made them out to be (simply because I don’t think it’s humanly possible for all of them to be as bad as Chaucer et al made them out to be), but imagine having your immortal soul in the hands of a guy who’s part lawyer, part used car salesman, part hippy-dippy community college professor, and part SJW Twitter slacktivist (with extra corruption, but minus even the minimal work ethic).

Severian, “Reformation”, Founding Questions, 2022-03-07.

August 12, 2025

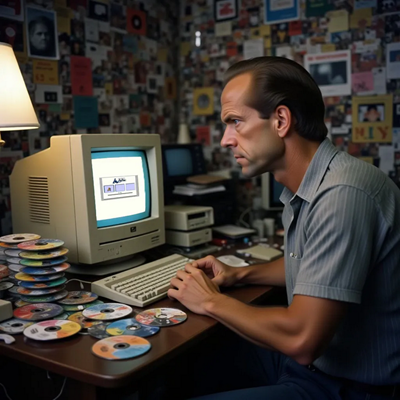

AOL to shut down its last dial-up access: dozens to be inconvenienced

James Lileks on the end-of-era announcement from AOL — and I can’t recall the last time I thought of that company — that they’ll be eliminating the last of their dial-up internet access accounts:

New tech: shiny today, tarnished tomorrow. Everything that was once bright and brilliant now stamps its walker towards the exit door. The headlines wave goodbye: Last telegram office in the US shut down.

Last phone booth in New York is decommissioned. The latest: AOL to shut off its landline customers.

You’d think this would be news on the level of “homing pigeon trainer employment hits record lows”.

Who uses dialup? Yahoo, which now owns the AOL brand, says that the user base is in the “low thousands”, which suggests that some people forgot to turn off autopay in 2005. What does AOL do today? The usual basket of dross and chum. A website that offers “trending videos” — gosh, don’t know where else you’d find those — and a lot of news stories, supplied by Yahoo, and its … numberless army of journalists, I guess.

It’s a legacy brand for people who want to slide into the internet like comfy slippers they left under the desk. And that’s fine. Facebook serves the same function. It’s a place to start, a home base. A familiar window out which we gaze daily We all have them. But let us not get nostalgic for AOL and the early days of the internet. Some people, of course, love to talk about the pioneer days, and how it required some technical know-how:

Well, we didn’t have those fancy little pre-made modems like you got in the 90s, so we had to get a little matchbox and fill it up with a certain kind of specially-bred insect that sang a note at a particular pitch when exposed to electrical current. So you’d crank up the generator and put the little alligator clips on the box and hold the box up to the phone while you entered your user name in Morse code by pushing on the hang-up buttons, and then you had to shake the box so the insect singing would modulate. Took about an hour, but then you’d be “On the Line”, as we said, and you could go to a Usenet group and call people Nazis. Kids today, they can call someone a Nazi without lifting a finger.

May 2, 2025

QotD: The Victorian attitude toward illegitimacy

Perhaps nothing divides us more profoundly from the Victorians than our attitude towards the illegitimate child (even the word illegitimate has almost disappeared from use in this context, as being unfairly stigmatising). That the sins of the parents should be visited upon children, by regarding those children themselves as tainted, seems morally monstrous to us, self-evidently cruel and unjust. We cannot even imagine — and I include myself — how anyone could be so morally primitive as to disdain a child merely because its parents were unmarried: and this is so however much we may believe in the virtues of marriage as an institution. The idea of fallen women also seems to us now to be horribly censorious, and hypocritical into the bargain: for no one ever spoke of fallen men, though they were essential to, the sine qua non of, the existence of fallen women.

I am still shocked by the recollection that, as late as the early 1990s, there were still a few women in psychiatric hospitals in Britain who were there principally because they had been admitted seventy years earlier after having given birth to an illegitimate child. No doubt they had quickly become institutionalised and could scarcely have coped with life outside; but to think of a long human life passed in this impoverished way (the wards for “chronics” had beds so close together that they allowed for no privacy whatever) as a kind of punishment for what is now no longer regarded even as an indiscretion, reminds one of La Rochefoucauld’s dictum that neither the sun nor death can be stared at for long. One cannot fix one’s mind on such a horrible injustice for long.

Of course, it was stigma like this that gave stigma itself a bad name — stigmatised so to speak, in fact, to such a degree or effect that the very name of stigma has a completely negative valency. No one has a good word to say for it, though whether there ever was, or could be, a society completely without it, I am unsure.

Theodore Dalrymple, “The Situational Nature of Scorn and Stigma”, New English Review, 2020-04-28.

February 16, 2025

QotD: Why we’re stagnating

I won’t attempt to recap here the many arguments that have been made recently about whether and how our society is stagnating. You could read this book or this book or this book. Or you could look at how economic productivity has stalled since 1971. Or you could puzzle over what else happened in 1971. Or you could read Patrick Collison’s list of how fast things used to happen, or ponder how practically every new movie these days is a sequel, or stare in shock at declines in scientific productivity. This new book by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber starts with a survey of the most damning indicators of stagnation, moves on to suggest some underlying causes, and then suggests an unexpected way out.

Their explanation for our doldrums is simple: we’re more risk averse, and we don’t care as much about the future. Risk aversion means stagnation, because any attempt to make things better involves risk: it could also make things worse, or it could fail and turn out to be a waste of time and money. Trying to invent a crazy new technology is risky, going into consulting or finance is safe. Investing in unproven startups or speculative bets is risky, investing in index funds is safe. Trying to overturn the scientific consensus is risky, keeping your head down and publishing papers that don’t say anything is safe. Producing challenging new art is risky, spewing an endless stream of Marvel superhero capeshit is safe. Even if, in every case, the safe option is the “rational” choice for an individual actor in maximin expected value terms, the sum total of these individually rational choices is a catastrophe for society.

So far this is a lame, almost tautological, explanation. Even if it’s all true, we still haven’t explained why people are so much more fearful of failure than they used to be. In fact, we would naively assume the opposite — society is much richer now, social safety nets much more robust, and in the industrialized world even the very poor needn’t fear starvation. In a very real sense, it’s never been safer to take risks. Failing as a startup founder or academic means you experience slightly lower lifetime earnings,1 while, in the great speculative excursions of the past, failure (and sometimes even success) meant death, scurvy, amputations, destitution, children sold into slavery or raised in poorhouses — basically unbounded personal catastrophe. And yet we do it less and less. Why?

Well, for starters, we aren’t the same people. Biologically, that is. We’re old, and old people tend to be more risk-averse in every way. Old people have more to lose. Old people also have less testosterone in their bloodstream. The population structure of our society has shifted drastically older because we aren’t having any children. This not only increases the relative number (and hence relative power) of older people, it also has direct effects on risk-aversion and future-orientation. People with fewer children have all their eggs in fewer baskets. They counsel those kids to go into safe professions and train them from birth to be organization kids. People with no children at all are disconnected from the far future, reinforcing the natural tendency of the elderly to favor consumption in the here and now over investment in a future they may never get to enjoy.

Old age isn’t the only thing that reduces testosterone levels. So does just living in the 21st century. The declines are broad-based, severe, and mysterious. Very plausibly they are downstream of microplastics and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals. The same chemicals may have feminizing effects beyond declines in serum testosterone. They could also be affecting the birth rate, one of many ways that these explanations all swirl around and flow into one another. Or maybe we don’t even need to invoke old age and microplastics to explain the decline in average testosterone of decisionmakers in our society. Many more of those decisionmakers are women, and women are vastly more risk-averse on average.2

John Psmith, “REVIEW: Boom, by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2024-11-11.

1. And given the logarithmic hedonic utility of additional money and fame, that hurts even less than it sounds like it would.

2. If you’re too lazy to read Jane’s review of Bronze Age Mindset but just want the evidence that women are more cautious and consensus-seeking than men on average, try this and this and this for starters.

December 27, 2024

QotD: Adapting to “permanent” food surpluses

We late-20th century Westerners are the only humans, in the entire history of our species, to have achieved permanent, society-wide caloric surplus. I’m well aware that it’s not actually permanent — it is, in fact, quite precarious, as the oddly-empty shelves at the local supermarket can confirm — but we have adapted as if it is. And I do mean adapted, in the full evolutionary sense — evolution is copious, local, and recent. Just as it doesn’t take more than a few generations of selective breeding to create an entire new breed of dog, so the human organism is fundamentally, physically different now than it was even a century ago.

More to the point, this is a testable hypothesis. I’m a history guy, obviously, not a biologist, but you don’t need to be a STEM PhD to see it. All our physical structures still look the same in 2021 as they did in 1901, but our biochemistry is far different. Just to take two obvious — and obviously detrimental — examples, we are awash in insulin and estrogen. Time warp in a laboring man from 1901 and feed him a modern “diet” for a week; the insulinemic effects of all that corn syrup etc. would put him in a coma. Even if he didn’t, the knock-on effect of all that insulin — greatly ramped-up estrogen — would deprive him of a lot of his physical strength, not to mention radically alter his mood, etc.

Severian, “The Experiment”, Founding Questions, 2021-09-25.

December 13, 2024

QotD: Nostalgia, or “they were better people back then”

That’s the thing about nostalgia: It assumes constant material progress. One can debate the origins and etymology of the term “nostalgia” – back in the 16th century, I think it was, they used it a few times to describe what we might call PTSD among soldiers – but it’s really a modern phenomenon. A Postmodern one, in truth — I’m talking late 20th century here. Humans have always longed for “the past”, but until the middle of the 20th century the “past” we longed for was mythical – the Golden Age, as opposed to our current Brass one.

The Golden Age was better because the Golden Men were better, not because their lives were materially better. There’s a reason all those medieval and Renaissance paintings show “historical” figures in contemporary garb, and it’s not because the Flemish Masters didn’t know about togas. Though they assumed the men of the Classical Past were better men, they assumed material life back then was pretty much the same as now, because it was pretty much the same as now. One can of course point to a million technological changes between the Roman Republic and the Renaissance, but life as it was actually lived by the vast majority of people was still basically the same: Up at dawn, to bed at dusk, birth and death and community life and subsistence farming, all basically the same. A world lit only by fire.

The modern age changed all that. At some point in the very near past, we started assuming tomorrow would look very different from today. And I do mean the very near past — there are probably people still alive today who remember people who assumed that tomorrow would be pretty much like today. Because, then, our lives are so materially different from even the very recent past, we tend to assume that our nostalgia is for material things. It’s very hard to put a name to something like the feeling “I wish we could have family Christmases again, sharing that one joke we had about how Uncle Bob always sends you goofy socks.” It’s very easy to put a name to something like “vinyl records” or “the Bob Newhart show” or “Betamax tapes”, so we use those as synecdoche.

In other words: Even though we could actually recreate the material world of 1983, and even though we think we want this, we don’t. We wish we could live like we lived in 1983, but very little of that has any relationship to the material culture of 1983.

Severian, “Nostalgia”, Founding Questions, 2021-10-19.

October 26, 2024

QotD: Henry VIII

Barbara Tuchman […] said something about medieval nobles once, to the effect of “the reason some of their decisions seems so childish to us is that a lot of them were children”. I don’t think she’s right about that — kids grew up pretty damn fast in the Middle Ages — but if you expand it a bit to “rookies make rookie mistakes”, she’s got a big, important point. No account of the reign of Henry VIII, for instance, can really be complete without considering that when he took the throne he was only 17, and had only been heir apparent for a few years before that. He was most definitely the “spare” in the old “heir and a spare” formula for medieval dynastic success; it’s likely that his father was preparing him for a Church career when his elder brother Arthur died suddenly in 1502, when Henry was 11. What Arthur had been in training his whole life to do, Henry got at most six frantic years of, under an increasingly feeble father.

Leaving all of Henry’s personal quirks aside — and his was a very strong, distinctive personality — that’s got to affect you.

So many of the changes in Henry’s reign, then, must have been driven in part by the fact that it was the same man, reflecting on a lifetime’s experience in a job he was never expected to have, wasn’t really prepared for, and didn’t seem to want (aside from the lifestyle). There’s been lots of pop-historical theorizing about what was “wrong” with the later Henry — senility, syphilis, the madness of power — but more naturalistic explanations of his later actions must take into account simple age. A man nearing the end of his life, knowing that his succession was very much in doubt and fearing for the state of his soul, will do things differently than a young man in the prime of life.

[…]

Life was hard back then, and cheap. When every other child dies before the age of five and the average life expectancy is 35, I imagine, you live your life cranked to 11 every waking moment. Accounts of grown men weeping like little girls at the theater aren’t an exaggeration; the whole age was given to extreme outbursts. And that’s just the baseline! Now consider that a guy like Henry never had a moment to himself, and I do mean never — not once, in his entire life. He even had a guy with him on the crapper, who would wipe his ass for him. The relationship between Henry and a guy like Wolsey, then — to say nothing of his relationship with the Groom of the Stool — must’ve been intimate in a way we can’t possibly grasp. Compared to that, you and your wife are barely on speaking terms. If Henry seemed sometimes to set policy just because he was pissed at Wolsey, we must consider the possibility that that’s exactly what happened.

The best you can do, then, is imagine yourself back there as best you can, and make your interpretations in that light, acknowledging your biases as best you can (I’m not a medievalist, obviously, but I’m a much better read amateur than most, and though Henry VIII is a very hard guy to like, he’s equally hard not to admire). Most of all — and this, I think, is the hardest thing for academic historians, more even than recognizing their presentist biases — you have to keep your humility. Perhaps Henry’s decision about ___ was part of a gay little frenemies spat with Wolsey. That’s sure what it seems like, knowing the man, and having no contrary evidence …

… but contrary evidence might always emerge. It might not have been the optimal decision, but it might’ve been a much better one than you thought, because Henry had information you didn’t, but now do. It makes for some restless nights, knowing that your life’s work could be overturned by some grad student finding some old paper at a yard sale somewhere, but … there it is.

Severian, “Writing Real History”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-08-18.

October 19, 2024

QotD: From blackberry picking to Bible verses

Last spring, my oldest daughter and I set out to tame our blackberry thicket. Half a dozen bushes, each with a decade’s worth of dead canes, had come with our house, and we were determined to make them accessible to hungry children. (Do you have any idea how much berries cost at the grocery store, even in the height of summer? Do you have an idea how many hours of peaceful book-reading you can stitch together out of the time your kids are hunting for fruit in their own yard? It’s a win-win.) But after we’d cut down all the dead canes, I explained that we also needed to shorten the living ones, especially the second-year canes that would be bearing fruit later in the summer. At this point, scratched and sweaty from our work, she balked: was Mom trying to deprive the children of their rightful blackberries? But I explained that on blackberries, like most woody plants, the terminal bud suppresses growth from all lower buds; removing it makes them all grow new shoots, each of which will have flowers and eventually fruit. Cutting back the canes in March means more berries in July. At which point I could see a light dawning in her eyes as she exclaimed, “Oh! We’re memorizing the Parable of the True Vine in school but I never knew why Jesus says pruning the vines makes more fruit …”

It’s pretty trite by now to point out that Biblical metaphors that would have made perfect sense for an agricultural society are opaque to a modern audience for whom vineyards are about the tasting room and trimming your wick extends the burn time of your favorite scented candle. There’s probably whole books out there exploring the material culture of first century Judaea to provide context to the New Testament.1 But at least pruning is a “known unknown”: John 15:2 jumps out as confusing, and anyone who does a little gardening can figure out the answer. Plenty of things aren’t like that at all. Even today, few people record the mundane details of their daily lives; in the days before social media and widespread literacy it was even more dramatic, so anyone who wants to know how our ancestors cleaned, or slept, or ate has to go poking through the interstices of the historical record in search of the answers — which means they need to recognize that there’s a question there in the first place. When they don’t, we end up with whole swathes of the past we can’t really understand because we’re unfamiliar with the way their inhabitants interacted with the physical world.

Jane Psmith, “REVIEW: The Domestic Revolution by Ruth Goodman”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-05-22.

1. Are they any good? Should I read them? I’ve mentally plotted out a structure for one of my own, where each chapter is themed around the main image of one of the parables — oil, wine, seeds, fish, sheep, cloth, salt — and explores all the practicalities: the wine chapter would cover viticulture techniques but also land ownership (were the vintners usually tenants? what did their workforce look like?), seeds would cover how grain was planted, harvested, milled, and cooked, etc. The only problem is that I don’t actually know anything about any of this.

October 11, 2024

“[T]he past is like a thriving civilization; they do things better there”

Another recommended link from the “Your Weekly Stack” set of links to interesting posts on Substack. This, like the previous post, is from an author I hadn’t read before and thought was worth sharing with you.

This is from The American Tribune, making the case that modern Americans (and westerners in general) are in a similar situation to the white minority in Rhodesia:

We stand today in the ruins of civilization. Much as the 9th Century Anglo-Saxons looked at the stone works of the Romans and thought they must have been giants,1 or the Greeks of the post-Sea Peoples Dark Age saw the works of the Minoans and Myceneans and thought only Cyclopses could have constructed such structures,2 we stare at the achievements of the 19th and early 20th Centuries in near-disbelief.

The moon hasn’t been stepped upon since the 70s. Mars remains uncolonized. Municipal infrastructure like water treatment and provision is falling apart and the government either can’t or won’t respond to natural disasters.3 Whereas we once built beautiful buildings that lasted for centuries, structures such as Chatsworth and the Horse Guards Building of Whitehall, now we have ugly structures of concrete and steel that are falling apart already.4

The situation as regards crime and squalor is even worse. As Curtis Yarvin notes in “An Open Letter to Open-Minded Progressives”:

If you read travel narratives of what is now the Third World from before World War II (I’ve just been enjoying Erna Fergusson’s Guatemala, for example), you simply don’t see anything like the misery, squalor and barbarism that is everywhere today. (Fergusson describes Guatemala City as “clean”. I kid you not.) What you do see is social and political structures, whether native or colonial, that are clearly not American in origin, and that are unacceptable not only by modern American standards but even by 1930s American standards.

So whereas Guatemala was once clean, now America’s cities are towers of concrete surrounded by piles of refuse, mobs of zombie-like drug addicts living on the streets,5 and infested with criminals of both the petty and highly violent variety. As Hartley put it, “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there”. More accurately, the past is like a thriving civilization; they do things better there.

In short, we, like those in the Belgian Congo after the Belgians left, live in an “Empire of Dust” where much of what remains is the ruin of a prior civilization destroyed not because it didn’t work, but because the demented ideology of the present conflicted with its continued, functional existence.6

What happened? A sort of decolonization inflicted upon the Great Powers themselves — namely America, Germany, Britain, and France — after the outlying colonies had long been destroyed. The decay of law and order, the promotion of anti-white hatred, the decay of infrastructure, and the filling of positions with corrupt thugs rather than honorable gentlemen,7 all of it is more or less what happened to the colonies in the ’50s and ’60s. Further, it is similar to what happened later on in South Africa, where a collection of communists, leftists, and NGOs with like mindsets and funded by those like George Soros turned a formerly thriving civilization into what now amounts to a land like Mad Max but with more murder.8

But while the South Africanization of America is certainly an issue that we face,9 it’s not the most accurate comparison to our present problem. South Africa was, when it fell, filled with decades of racial hatred sparked by decades of apartheid that ended only then (though was somewhat overblown), something that Europe never had and nowhere in America has had in over half a century. That unique circumstance created a degree of hatred that was overpowering and, though one with which we largely disagree, understandable. We, then, are somewhat different in terms of where we are and what is happening.

1. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/data/UQ_363155/s40110183_phd_final_thesis_copy.pdf

2. See The Glory that Was Greece by Stobart

3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jackson,_Mississippi_water_crisis; https://nypost.com/2024/10/03/us-news/north-carolina-hurricane-victims-slam-biden-harris-admin-as-fema-response-sputters/

4. See, for example, https://www.vintagebuilding.com/houses-longer-houses/

5. See, for example: https://youtu.be/9iSkKkzabnM

6. This is what the phrase “empire of dust” comes from: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2148945/

7. https://www.theamericantribune.news/p/the-death-of-the-gentleman-and-the

8. https://www.theamericantribune.news/p/george-soross-hand-in-south-africas

9. I wrote an article on this for Tablet: https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/united-states-south-africa-racial-justice

October 6, 2024

QotD: Putting the past on trial

If you pass through Tavistock Square in Bloomsbury, London, you might happen upon a statue of Virginia Woolf that was erected in 2004. You will already know that Woolf was a leading figure in the Bloomsbury Set, that coterie of artists and intellectuals that included E. M. Forster, John Maynard Keynes and Lytton Strachey. But if you scan the QR code next to this statue you can also learn that Woolf was a vile racist who must be condemned by all right-thinking individuals.

Historical context is all very well. When it comes to Woolf, perhaps a few details about her novels To the Lighthouse or Mrs Dalloway would be appreciated, or some information about her relationship with Vita Sackville-West. But no, instead we are to be hectored about her “challenging, offensive comments and descriptions of race, class and ability which would find unacceptable today”. One wonders what the person responsible for these judgmental remarks has ever accomplished, if anything at all. These petty moralists are like the crabs in the bucket, pulling down the most accomplished out of envy and spite.

The best approach to writers of genius is humility, but this quality seems to be on the decline. We see evidence of this in the self-importance of those who have rewritten books by P.G. Wodehouse, Ian Fleming, Agatha Christie and Roald Dahl. It should go without saying that Wodehouse’s prose cannot be improved, least of all by know-nothing activists who have inveigled their way into the publishing industry.

I recently bought the complete set of Fleming’s James Bond books, but I had to seek out second-hand copies to ensure that they had not been sanitised by talentless “sensitivity readers”. Yes of course, these books include sentiments that are unacceptable by today’s standards. But what’s so wrong with that? “All women love semi-rape” is a shocking sentence – in this case, it’s by the female narrator of The Spy Who Loved Me (1962) – but what purpose does censoring the passage actually serve?

The rewriting of books and the creation of cautionary QR codes are symptoms of our current strain of puritanism. These are the descendants of those religious zealots who shut the theatres in 1642 out of fear that the masses might be corrupted. And while I concede that Ian Fleming’s views on relationships between the sexes may not have been progressive, I don’t feel the need to be berated about it before enjoying the adventures of James Bond.

It’s not as though Bond is even meant to be a likeable character; the man has a licence to kill, for heaven’s sake. This isn’t someone you’d wish to invite to a dinner party. In that regard he’s reminiscent of the hero of George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman series, a character based on the bully from Tom Brown’s School Days by Thomas Hughes. He’s a violent boorish rapist, but the novels are still entertaining because most of us aren’t reading them for moral instruction.

In exploring the gamut of human experience, writers will often feel compelled to recreate the grotesque, the uncomfortable, the outrageous, even the downright evil. Who ever supposed that works of fiction should restrict themselves to rose-tinted idealisations of human existence? Imagine Macbeth without the regicide, or King Lear without the eye-gouging, or Titus Andronicus without the cannibalism. Would Dante’s Divine Comedy retain its power if some “sensitivity reader” excised the Inferno?

Andrew Doyle, “Putting the past on trial”, Andrew Doyle, 2024-07-04.

September 8, 2024

QotD: Life in pre-mechanical times

Anyway, because I’m actually interested in how people are and how they lived, I love “living history”. I know, I know, I’m the one who brought up the Civil War, but though I admire (in a very limited sense) the dedication of “reenactors”, we ain’t going there, lest the comments get way off track. Instead, I’ll refer you to the works of Ruth Goodman. She apparently shows up on a lot of “living history” shows in Britain, which are apparently quite popular over there, and she writes good books about the experience, most with “How to” in the title: I’ve read How to be a Victorian and How to be a Tudor, and they’re both great fun.

The thing you’ll notice right away if you read them is how utterly tedious life was pre-electricity. Actually, no, tedious is the wrong word, since in our usage it implies “mindless” and that’s exactly the opposite of Victorian and especially Tudor life. A much better word is “laborious”, maybe even just “hard”. Life was hard back then. Even the simplest tasks took hours, because everything had to be done by hand. You had a few simple machines, of course — simple in the mechanical sense, though nearly every page brings its “gosh, I never would’ve thought of that!” surprise — but mostly it’s muscle power. If you’re lucky, a horse’s or a donkey’s muscles do some of the heaviest work, but mostly it’s straight-up human effort.

And it’s far from mindless. How to be a Tudor has a long section on baking bread, for instance, and it’s fascinating. There’s a reason bakers had their own guild and were considered tradesmen; it takes a lot of well-honed skill to make anything but the coarsest peasant stuff. And of course that coarse peasant stuff takes a decent amount of skill itself, which is just one of a zillion little skills your average housewife would have. If you read the section on bread-baking and really try to imagine doing it, you’ll find yourself almost physically exhausted … and that’s just one minor chore among dozens, maybe hundreds, that everyday people had to do each and every day.

In other words, everyday Tudor people were “simple”, in the old sense that means “unsophisticated”, but they were never, ever bored. Even the relatively well-off, even when everything was peaceful and prosperous and functioning perfectly, were constantly mentally engaged with the world. They had to be. Imagine if getting your daily bread took not just two hours’ labor, but an actual plan. If you didn’t start your day figuring out how you were going to get fed that day, you wouldn’t eat. They had dozens, probably hundreds, more daily tasks than we ever have, and while any one of those tasks can probably be performed on autopilot if taken in isolation, they were never taken in isolation. Maybe the housewife could bake bread on autopilot, but while her hands were doing that seemingly of their own volition, her mind was lining up the zillion other things she had to do that day. Her mind was constantly engaged.

And “housewife” was a deeply meaningful term back then. The next thing that strikes you, after the sheer amount of effort everything took, is the necessity of communal life. Just the basics of day-to-day living pretty much requires a nuclear family — husband, wife, a few kids. And that’s your hardy yeoman type on the edge of starvation on the forest’s fringes. In any larger settlement, everyone knows everyone, intimately, because your very life depends on it — not only do you know the miller personally, you’ve got a major, indeed mortal, interest in how he lives his life, because if he’s shorting you, you die … or, at least, your already hard life gets a whole lot harder. There’s basically no such thing as privacy, because there can’t be.

Severian, “On Boredom”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-08-17.

April 10, 2024

QotD: Aprons

It’s like the thing with the aprons, that science fiction writers older than I think that Heinlein was a sexist, because he has women wearing aprons. Instead of “Everyone who worked with staining liquids and fire wore aprons. Because clothes were insanely expensive, that’s why.” We stopped wearing aprons [because today] a pack of t-shirts at WalMart is $10. Nothing to do with sexism.

Sarah Hoyt, “Teaching Offense”, According to Hoyt, 2019-10-25.