I want to start with the observation I offer whenever I am asked (and being a Romanist, this happens frequently) “why did Rome fall?” which is to note that in asking that question we are essentially asking the wrong question or at least a less interesting one. This will, I promise, come back to our core question about diversity and the fall of Rome but first we need to frame this issue correctly, because Rome fell for the same reason all empires fall: gravity.

An analogy, if you will. Imagine I were to build a bridge over a stream and for twenty years the bridge stays up and then one day, quite unexpectedly, the bridge collapses. We can ask why the bridge fell down, but the fundamental force of gravity which caused its collapse was always working on the bridge. As we all know from our physics classes, the force of gravity was always active on the bridge and so some other set of forces, channeled through structural elements was needed to be continually resisting that downward pressure. What we really want to know is “what force which was keeping the bridge up in such an unnaturally elevated position stopped?” Perhaps some key support rotted away? Perhaps rain and weather shifted the ground so that what once was a stable position twenty years ago was no longer stable? Or perhaps the steady work of gravity itself slowly strained the materials, imperceptibly at first, until material fatigue finally collapse the bridge. Whatever the cause, we need to begin by conceding that, as normal as they may seem to us, bridges are not generally some natural construction, but rather a deeply unnatural one, which must be held up and maintained through continual effort; such a thing may fail even if no one actively destroys it, merely by lack of maintenance or changing conditions.

Large, prosperous and successful states are always and everywhere like that bridge: they are unnatural social organizations, elevated above the misery and fragmentation that is the natural state of humankind only by great effort; gravity ever tugs them downward. Of course when states collapse there are often many external factors that play a role, like external threats, climate shifts or economic changes, though in many cases these are pressures that the state in question has long endured. Consequently, the more useful question is not why they fall, but why they stay up at all.

And that question is even more pointed for the Roman Empire than most. While not the largest empire of antiquity, the Roman empire was very large (Walter Scheidel figures that, as a percentage of the world’s population at the time, the Roman Empire was the fifth largest ever, rare company indeed); while not the longest lasting empire of antiquity, it did last an uncommonly long time at that size. It was also geographically positioned in a space that doesn’t seem particularly well-suited for building empires in. While the Mediterranean’s vast maritime-highway made the Roman Empire possible, the geography of the Mediterranean has historically encouraged quite a lot of fragmentation, particularly (but not exclusively) in Europe. Despite repeated attempts, no subsequent empire has managed to recreate Rome’s frontiers (the Ottomans got the closest, effectively occupying the Roman empire’s eastern half – with a bit more besides – but missing most of the west).

The Roman Empire was also, for its time, uncommonly prosperous. As we’ll see, there is at this quite a lot of evidence to suggest that the territory of the Roman Empire enjoyed a meaningfully higher standard of living and a more prosperous economy during the period of Roman control than it did either in the centuries directly before or directly after (though we should not overstate this to the point of assuming that Rome was more prosperous than any point during the Middle Ages). And while the process of creating the Roman empire was extremely violent and traumatic (again, a recommendation for G. Baker, Spare No One: Mass Violence in Roman Warfare (2021) for a sense of just how violent), subsequent to that, the evidence strongly suggests that life in the interior Roman Empire was remarkably peaceful during that period, with conflicts pushed out of the interior to the frontiers (though I would argue this almost certainly reflects an overall decrease in the total amount of military conflict, not merely a displacement of it).

The Roman Empire was thus a deeply unnatural, deeply unusual creature, a hot-house flower blooming untended on a rocky hillside. The question is not why the Roman empire eventually failed – all states do, if one takes a long enough time-horizon – but why it lasted so long in such a difficult position. Of course this isn’t the place to recount all of the reasons why the Roman Empire held together for so long, but we can focus on a few which are immediately relevant to our question about diversity in the empire.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part V: Saving and Losing and Empire”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-07-30.

December 4, 2024

QotD: What caused the (western) Roman Empire to fall?

November 28, 2024

QotD: The trace italienne in fortification design

Now I should note that the initial response in Italy to the shocking appearance of effective siege artillery was not to immediately devise an almost entirely new system of fortifications from first principles, but rather – as you might imagine – to hastily retrofit old fortresses. But […] we’re going to focus on the eventual new system of fortresses which emerge, with the first mature examples appearing around the first decades of the 1500s in Italy. This system of European gunpowder fort that spreads throughout much of Europe and into the by-this-point expanding European imperial holdings abroad (albeit more unevenly there) goes by a few names: “bastion” fort (functional, for reasons we’ll get to in a moment), “star fort” (marvelously descriptive), and the trace italienne or “the Italian line”. since that was where it was from.

Since the goal remains preventing an enemy from entering a place, be that a city or a fortress, the first step has to be to develop a wall that can’t simply be demolished by artillery in a good afternoon or two. The solution that is come upon ends up looking a lot like those Chinese rammed earth walls: earthworks are very good at absorbing the impact of cannon balls (which, remember, are at this point just that: stone and metal balls; they do not explode yet): small air pockets absorb some of the energy of impact and dirt doesn’t shatter, it just displaces (and not very far: again, no high explosive shells, so nothing to blow up the earthwork). Facing an earthwork mound with stonework lets the earth absorb the impacts while giving your wall a good, climb-resistant face.

So you have your form: a stonework or brick-faced wall that is backed up by essentially a thick earthen berm like the Roman agger. Now you want to make sure incoming cannon balls aren’t striking it dead on: you want to literally play the angles. Inclining the wall slightly makes its construction easier and the end result more stable (because earthworks tend not to stand straight up) and gives you an non-perpendicular angle of impact from cannon when they’re firing at very short range (and thus at very low trajectory), which is when they are most dangerous since that’s when they’ll have the most energy in impact. Ideally, you’ll want more angles than this, but we’ll get to that in a moment.

Because we now have a problem: escalade. Remember escalade?

Earthworks need to be wide at the base to support a meaningful amount of height, tall-and-thin isn’t an option. Which means that in building these cannon resistant walls, for a given amount of labor and resources and a given wall circuit, we’re going to end up with substantially lower walls. We can enhance their relative height with a ditch several out in front (and we will), but that doesn’t change the fact that our walls are lower and also that they now incline backwards slightly, which makes them easier to scale or get ladders on. But obviously we can’t achieved much if we’ve rendered our walls safe from bombardment only to have them taken by escalade. We need some way to stop people just climbing over the wall.

The solution here is firepower. Whereas a castle was designed under the assumption the enemy would reach the foot of the wall (and then have their escalade defeated), if our defenders can develop enough fire, both against approaching enemies and also against any enemy that reaches the wall, they can prohibit escalade. And good news: gunpowder has, by this point, delivered much more lethal anti-personnel weapons, in the form of lighter cannon but also in the form of muskets and arquebuses. At close range, those weapons were powerful enough to defeat any shield or armor a man could carry, meaning that enemies at close range trying to approach the wall, set up ladders and scale would be extremely vulnerable: in practice, if you could get enough muskets and small cannon firing at them, they wouldn’t even be able to make the attempt.

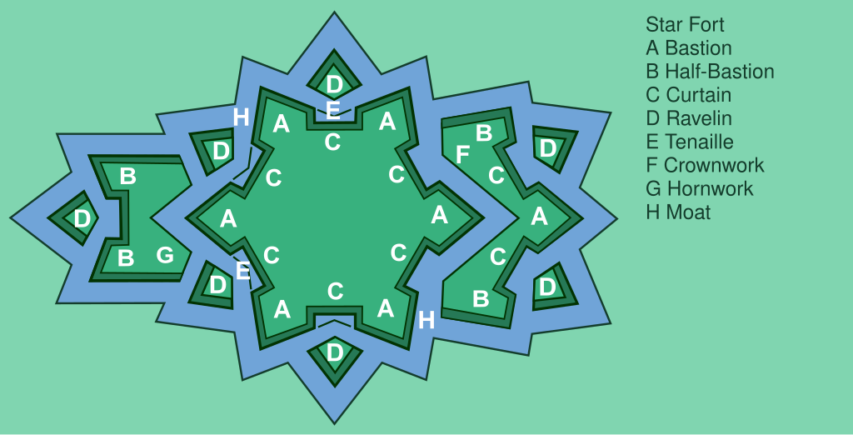

But the old projecting tower of the castle, you will recall, was designed to allow only a handful of defenders fire down any given section of wall; we still want that good enfilade fire effect, but we need a lot more space to get enough muskets up there to develop that fire. The solution: the bastion. A bastion was an often diamond or triangular-shaped projection from the wall of the fort, which provided a longer stretch of protected wall which could fire down the length of the curtain wall. It consists of two “flanks” which meet the curtain wall and are perpendicular to it, allowing fire along the wall; the “faces” (also two) then face outward, away from the fort to direct fire at distant besiegers. When places at the corners of forts, this setup tends to produce outward-spiked diamonds, while a bastion set along a flat face of curtain wall tends to resemble an irregular pentagon (“home plate”) shape [Wiki]. The added benefit for these angles? From the enemy siege lines, they present an oblique profile to enemy artillery, making the bastions quite hard to batter down with cannon, since shots will tend to ricochet off of the slanted line.

In the simplest trace italienne forts [Wiki], this is all you will need: four or five thick-and-low curtain walls to make the shape, plus a bastion at each corner (also thick-and-low, sometimes hollow, sometimes all at the height of the wall-walk), with a dry moat (read: big ditch) running the perimeter to slow down attackers, increase the effective height of the wall and shield the base of the curtain wall from artillery fire.

But why stay simple, there’s so much more we can do! First of all, our enemy, we assume, have cannon. Probably lots of cannon. And while our walls are now cannon resistant, they’re not cannon immune; pound on them long enough and there will be a breach. Of course collapsing a bastion is both hard (because it is angled) and doesn’t produce a breach, but the curtain walls both have to run perpendicular to the enemy’s firing position (because they have to enclose something) and if breached will allow access to the fort. We have to protect them! Of course one option is to protect them with fire, which is why our bastions have faces; note above how while the flanks of the bastions are designed for small arms, the faces are built with cannon in mind: this is for counter-battery fire against a besieger, to silence his cannon and protect the curtain wall. But our besieger wouldn’t be here if they didn’t think they could decisively outshoot our defensive guns.

But we can protect the curtain further, and further complicate the attack with outworks [Wiki], effectively little mini-bastions projecting off of the main wall which both provide advanced firing positions (which do not provide access to the fort and so which can be safely abandoned if necessary) and physically obstruct the curtain wall itself from enemy fire. The most basic of these was a ravelin (also called a “demi-lune”), which was essentially a “flying” bastion – a triangular earthwork set out from the walls. Ravelins are almost always hollow (that is, the walls only face away from the fort), so that if attackers were to seize a ravelin, they’d have no cover from fire coming from the main bastions and the curtain wall.

And now, unlike the Modern Major-General, you know what is meant by a ravelin … but are you still, in matters vegetable, animal and mineral, the very model of a modern Major-General?

But we can take this even further (can you tell I just love these damn forts?). A big part of our defense is developing fire from our bastions with our own cannon to force back enemy artillery. But our bastions are potentially vulnerable themselves; our ravelins cover their flanks, but the bastion faces could be battered down. We need some way to prevent the enemy from aiming effective fire at the base of our bastion. The solution? A crownwork. Essentially a super-ravelin, the crownwork contains a full bastion at its center (but lower than our main bastion, so we can fire over it), along with two half-bastions (called, wait for it, “demi-bastions”) to provide a ton of enfilade fire along the curtain wall, physically shielding our bastion from fire and giving us a forward fighting position we can use to protect our big guns up in the bastion. A smaller version of the crownwork, called a hornwork can also be used: this is just the two half-bastions with the full bastion removed, often used to shield ravelins (so you have a hornwork shielding a ravelin shielding the curtain wall shielding the fort). For good measure, we can connect these outworks to the main fort with removable little wooden bridges so we can easily move from the main fort out to the outworks, but if the enemy takes an outwork, we can quickly cut it off and – because the outworks are all made hollow – shoot down the attackers who cannot take cover within the hollow shape.

An ideal form of a bastion fortress to show each kind of common work and outwork.

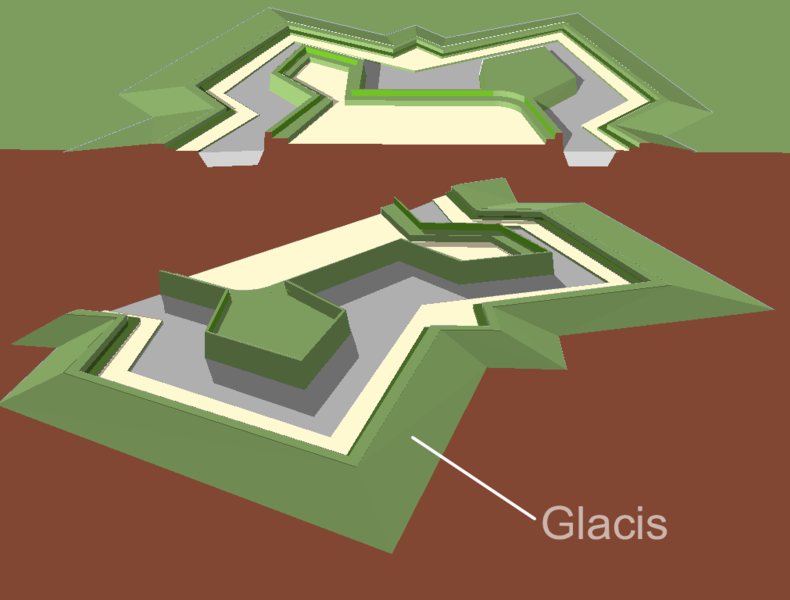

Drawing by Francis Lima via Wikimedia Commons.We can also do some work with the moat. By adding an earthwork directly in front of it, which arcs slightly uphill, called a glacis, we can both put the enemy at an angle where shots from our wall will run parallel to the ground, thus exposing the attackers further as they advance, and create a position for our own troops to come out of the fort and fire from further forward, by having them crouch in the moat behind the glacis. Indeed, having prepared, covered forward positions (which are designed to be entirely open to the fort) for firing from at defenders is extremely handy, so we could even put such firing positions – set up in these same, carefully mathematically calculated angle shapes, but much lower to the ground – out in front of the glacis; these get all sorts of names: a counterguard or couvreface if they’re a simple triangle-shape, a redan if they have something closer to a shallow bastion shape, and a flèche if they have a sharper, more pronounced face. Thus as an enemy advances, defending skirmishers can first fire from the redans and flèches, before falling back to fire from the glacis while the main garrison fires over their heads into the enemy from the bastions and outworks themselves.

A diagram showing a glacis supporting a pair of bastions, one hollow, one not.

Diagram by Arch via Wikimedia Commons.At the same time, a bastion fortress complex might connect multiple complete circuits. In some cases, an entire bastion fort might be placed within the first, merely elevated above it (the term for this is a “cavalier“) so that both could fire, one over the other. Alternately, when entire cities were enclosed in these fortification systems (and that was common along the fracture zones between the emerging European great powers), something as large as a city might require an extensive fortress system, with bastions and outworks running the whole perimeter of the city, sometimes with nearly complete bastion fortresses placed within the network as citadels.

Fort Saint-Nicolas, which dominates the Old Port of Marseille. The fort forms part of a system with the low outwork you see here and also an older refitted castle, Fort Saint-Jean, on the other side of the harbor.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.All of this geometry needed to be carefully laid out to ensure that all lines of approach were covered with as much fire as possible and that there were no blindspots along the wall. That in turn meant that the designers of these fortresses needed to be careful with their layout: the spacing, angles and lines all needed to be right, which required quite a lot of math and geometry to manage. Combined with the increasing importance of ballistics for calculating artillery trajectories, this led to an increasing emphasis on mathematics in the “science of warfare”, to the point that some military theorists began to argue (particularly as one pushes into the Enlightenment with its emphasis on the power of reason, logic and empirical investigation to answer all questions) that military affairs could be reduced to pure calculation, a “hard science” as it were, a point which Clausewitz (drink!) goes out of his way to dismiss (as does Ardant du Picq in Battle Studies, but at substantially greater length). But it isn’t hard to see how, in the heady centuries between 1500 and 1800 how the rapid way that science had revolutionized war and reduced activities once governed by tradition and habit to exercises in geometry, one might look forward and assume that trend would continue until the whole affair of war could be reduced to a set of theorems and postulates. It cannot be, of course – the problem is the human element (though the military training of those centuries worked hard to try to turn men into “mechanical soldiers” who could be expected to perform their role with the same neat mathmatical precision of a trace italienne ravelin). Nevertheless this tension – between the science of war and its art – was not new (it dates back at least as far as Hellenistic military manuals) nor is it yet settled.

An aerial view of the Bourtange Fortress in Groningen, Netherlands. Built in 1593, the fort has been restored to its 1750s configuration, seen here.

Photo by Dack9 via Wikimedia Commons.But coming back to our fancy forts, of course such fortresses required larger and larger garrisons to fire all of the muskets and cannon that their firepower oriented defense plans required. Fortunately for the fortress designers, state capacity in Europe was rising rapidly and so larger and larger armies were ready to hand. That causes all sorts of other knock on effects we’re not directly concerned with here (but see the bibliography at the top). For us, the more immediate problem is, well, now we’ve built one of these things … how on earth does one besiege it?

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part IV: French Guns and Italian Lines”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-12-17.

November 19, 2024

The state and society

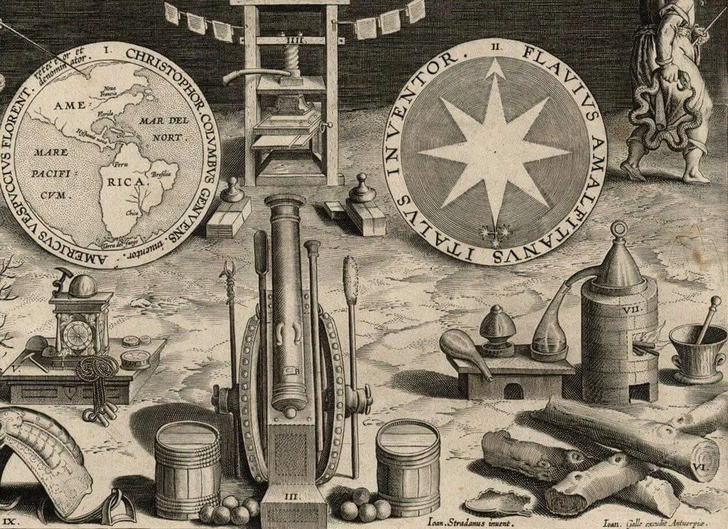

Lorenzo Warby explains why Karl Marx was wrong about the origins of what he called “the three great inventions” and therefore also mistaken about the societal impact of those inventions:

Gunpowder, the compass, and the printing press were the 3 great inventions which ushered in bourgeois society. Gunpowder blew up the knightly class, the compass discovered the world market and founded the colonies, and the printing press was the instrument of Protestantism and the regeneration of science in general; the most powerful lever for creating the intellectual prerequisites.

Karl Marx, “Division of Labour and Mechanical Workshop. Tool and Machinery” in Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63, Part 3) Relative Surplus Value.

With this quote we can see what is wrong both with Marx’s notion of the role of technology in social causation and with a very common notion of the relationship between state and society.

The false — but very common — view of the relationship of state and society is that the state is a product of its society, that the state emanates from its society. This gets the dominant relationship almost entirely the wrong way around. It is far more true to say that the state is a fundamental structuring element of the social dynamics of the territory it rules rather than the reverse.

It is perhaps easiest to see this by noting the glaring flaw in Marx’s reasoning. The gunpowder, the compass and the printing press were all originally Chinese inventions. Indeed, Europe acquired — via intermediaries — gunpowder and the compass from China. (Gutenberg’s printing press appears to have been an independent invention.)

Source: Nova Reperta Frontispiece, 1588.

Yet, as Marx was very well aware, China did not develop a bourgeoisie in his sense. Indeed, Marx’s notion of the Asiatic mode of production grappled with precisely that lack.1

In 1620, Sir Francis Bacon wrote in his Instauratio magna that

… printing, gunpowder, and the nautical compass … have altered the face and state of the world: first, in literary matters; second, in warfare; third, in navigation …

This was true of the effect of these inventions in European, but not Chinese, hands.

Why were these inventions globally transformative in European, but not Chinese hands? Because of the differences in the structure of European state(s) compared to the Chinese state.

Unified China …

The first difference is that the European states were states, plural. Europe had competitive jurisdictions, it had centuries of often intense inter-state conflict. From the Sui (re)unification (581) onwards China was, with brief interruptions, a single polity.2 What the evidence — both Chinese and Roman — shows quite clearly is that civilisational unity in a single polity is bad for institutional, technological and intellectual development.

The second difference is with the internal structure of European states compared to the Chinese state. The Sui dynasty, by introducing the Keju, the imperial examination — refining the use of appointment by exam that went back to the Warring States period — created a structure that directed Chinese human capital to the service of the Emperor.

There were three tiers of examinations (local, provincial, palace). You could sit for them as often as you wished. So a significant proportion of Chinese males devoted decades of their lives to attempting to pass the exams. Over time, the exams became more narrowly Confucian — probably because it required a high level of detailed mastery, so had more of a sorting effect — thereby promoting intellectual conformism.

[…]

… and divided Europe

Conversely, when gunpowder, the compass and the printing press came to Europe, European states already had a military aristocracy; self-governing cities; an armed mercantile elite; organised religious structures; so a rich array of cooperative institutions. Moreover, kin-groups had been suppressed across manorial Europe, forcing — or giving the social space for — alternative mechanisms for social cooperation to evolve.3, 4 In particular, due [to] its self-governing cities with armed militias, medieval Europe had an (effectively) armed mercantile elite before gunpowder, the compass or printing reached Europe.

Alfonso IX of Leon and Galicia (r.1188-1230) first summoned the Cortes of Leon in 1188. This became the start of the first institutionalised use of merchant representatives in deliberative assemblies. Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (r.1155-1190) had tried something similar earlier, but the mercantile elites of North Italy preferred de facto independence, defeating him at the Battle of Legnano in 1176.

The first European reference to the compass is in a text written some time between 1187 and 1202, with its use appearing to expand over the 1200s. The first reference to gunpowder in Europe is not until 1267 and it took centuries before gunpowder played a major role in European warfare.

Both the compass and gunpowder really only have transformative effects from the late C15th onwards, which is also when the printing press is spreading across Latin Europe. By that time, medieval Europe has already become a machine culture and it had been for centuries the civilisation with the most powerful mercantile elite. A reality driven by competitive jurisdictions, a rural-based military aristocracy, law that was not based on revelation (so it could entrench social bargains), suppression of kin-groups, and self-governing cities.

Competition between European states was a powerful driver of the transformative use of technologies. But so was the level of striving within such states: adventurers able to mobilise resources — and seeking wealth, power, prestige — had far more room to operate (and receive official sanction) in Europe than in China.

In other words, the differences in the development and use of technology — and in social dynamics and formations — between China and medieval Europe was fundamentally driven by the differences in state structures, in how the relevant polities worked.

1. Marx was not an honest intellectual reasoner:

As to the Delhi affair, it seems to me that the English ought to begin their retreat as soon as the rainy season has set in in real earnest. Being obliged for the present to hold the fort for you as the Tribune’s military correspondent I have taken it upon myself to put this forward. NB, on the supposition that the reports to date have been true. It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way.

Marx to Engels, [London,] 15 August 1857, (emphasis in the original).2. The Song (960-1279) failed to fully unify China, but they were the only significant Han polity. That the Song were effectively within a mini-state system does seem to have affected their policies, including the unusually — for a Chinese imperial dynasty — strong focus on trade and technological development.

3. Kin-groups had already been suppressed in the city-states of the Classical world, including Rome. They re-emerged with the incoming Germanic peoples, and then were suppressed again by the Church and the manorial elite, remaining in the agro-pastoralist Celtic fringe and Balkan uplands.

4. Economists Avner Greif and Guido Tabellini define clan (i.e. kin-group) as “a kin-based organization consisting of patrilineal households that trace their origin to a (self-proclaimed) common male ancestor“. They contrast this with a corporation: “a voluntary association between unrelated individuals established to pursue common interests“. They note they perform similar functions: “they sustained cooperation among members, regulated interactions with non-members, provided local public or club goods, and coordinated interactions with the market and with the state“. Triads, tongs and cults can also perform these functions.

November 12, 2024

John Carter – “We can all sense the vibe shift”

At Postcards From Barsoom, John Carter tries to explain the “vibe shift” in western culture:

The Course of Empire – Destruction by Thomas Cole, 1836.

From the New York Historical Society collection via Wikimedia Commons.

Underneath the medical tyranny of COVID, the stolen elections, the Internet censorship, the inflation, the hypermigration, the gender psychosis, the polarized rancor of sexual politics, and all of the rest of the symptoms of our decaying mismanagerial order, a countercurrent has flowed through the deep and hidden places of our collective psyche, hot and slow, like a chthonic river of magma rising implacably to the surface.

It isn’t just frustration with the intolerable imposition of Woke into every aspect of our lives, as though we could reset the clock to 90s liberalism and get fresh again with the Prince of Bel Air. It isn’t just anger at the invasion of our countries by the third world, nor is it limited to impatient disgust with the glossolalic babble of an incompetocracy comprised of credentialed midwits who seem to feel that word-shaped noises confer all the legitimacy they need to misrule our countries into oblivion.

It isn’t purely negative.

There’s a sense, somehow, of hope.

Hope, that after decades in which it seemed that history has stalled, that the culture has been frozen in permafrost, that nothing new could ever really be done again, that Nothing Ever Happens, that the only thing we can look forward to is a long, cold decline into technocratic surveillance, demographic implosion, green energy poverty, and final, irrecoverable collapse … hope that maybe this insipid fate isn’t so inevitable as we thought. Hope, that the building tectonic pressure of those buried psychological forces might finally break through and crack the shell of a dead future.

The sudden birth of artificial intelligence and the renewed enthusiasm for the conquest of space are two very obvious signs of this abrupt return of novelty. This is not a purely positive thing – AI is regarded with anxiety by almost everyone, but it is the raw fact of its sudden transition from science fiction to mundane tool of everyday life that is significant here.

There are other signs of this sense of renewal. The proliferation of self-improvement culture amongst many of the youth, particularly on the Very Online Right. The rise of the digital nomad, a modern re-enactment of the Romantic wanderjahr. The quiet birth of the network state, for instance in the form of Praxis. The renaissance of thoughtful, long-form essays right here on Substack. Surging interest in the religious traditions of our ancestors, whether in the form of Orthodox Christianity or paganism. The transformation of warfare by drones, promising a revolution in military affairs every bit as epochal as the firearm. The rise of a contradictorily global sense of national particularism. The steady refinement of 3D printing technologies.

Trump’s victory in 2024 seems a sure sign of this vibe shift. In a plot arc that could have been lifted straight from the original Star Wars trilogy, Trump brought A New Hope to America – and the world – in 2016; his forces were shattered and scattered to the winds in 2020 when The Empire Struck Back; only for the rebel forces, tempered by the lessons learned in defeat and strengthened with the assistance of new allies, to Return With the Jedi in 2024 and once again blow up the Death Star. This time around, Trump represents not simply the desperate holding action of an underground resistance to granny state totalitarianism, but the coalescence of a new and vigorous counter-elite, as embodied most of all by the ambitious hectobillionaire space lord who built auctoritas by buying the digital public square out from under the Empire so he could shitpoast in peace with the chuds.

Each of these has their good and bad aspects – the point, again, is not to dwell on whether any given development will be to our benefit or our detriment. As always, the ramification of second and third-order effects through the social order will result in both advantage and disadvantage. The point is simply that things are changing, that we can all feel it, and that this fuels a sense of nervous excitement that permeates the atmosphere like electrical buzz of a high-tension wire. Perhaps there will be disaster, and we shall drive ourselves to ruin and extinction; perhaps our descendants will walk the stars as near-gods. Either way, we are here, now, at this most interesting of nexus points in the unfolding history of our species. Would you rather be anywhen else?

The pessimism of recent years naturally generated an interest in cyclical theories of history – the empirical Strauss-Howe model of generational turnings, Turchin’s mechanical cliodynamics with its elite overproduction and wealth pumps, Spengler’s mythopoetic conception of cultures as vast organisms whose lifecycles progress through predictable seasons. Hard times make strong men; strong men make good times; good times make weak men; weak men make hard times. Whichever model one favours, the invariable conclusion is that Western civilization is in its terminal winter – fragile, ossified, decadent, corrupt, exhausted, and doomed. Desolation awaits.

“The Course of Empire – Desolation” by Thomas Cole, one of a series of five paintings created between 1833 and 1836.

Wikimedia Commons.Yet a cycle is not defined by its final product, no more than a symphony is defined by its concluding note, a life by its last moment, a wheel by a single turn, or a circle by a single point. Viewed from another angle, the death of Faustian civilization is also the birth of a new civilization … and even as we are here to live through the death of one, we plant the seeds for the other. With the tempo of history moving faster than ever before due to the global interconnectivity of instantaneous telecommunications and high-speed travel, it may be that our children will live in the savage springtime of that new civilization … perhaps one animated by the Aenean rather than the Faustian soul, which “will go Mars, not because it is hard, but because it is necessary”. You should read the essay at that last link, by the way. It isn’t long, it’s extremely interesting, and it’s new.

November 4, 2024

QotD: Early raids on, and sieges of, fortified cities

We’ve gone over this before, but we should also cover the objectives the attacker generally has in a siege. In practice, we want to think about assaults fitting into two categories: the raid and the siege, with these as distinct kinds of attack with different objectives. The earliest fortifications were likely to have been primarily meant to defend against raids rather than sieges as very early (Mesolithic or Neolithic) warfare seems, in as best we can tell with the very limited evidence, to have been primarily focused on using raids to force enemies to vacate territory (by making it too dangerous for them to inhabit by inflicting losses). Raids are typically all about surprise (in part because the aim of the raid, either to steal goods or inflict casualties, can be done without any intention to stick around), so fortifications designed to resist them do not need to stop the enemy, merely slow them down long enough so that they can be detected and a response made ready. […]

In contrast, the emergence of states focused on territorial control create a different set of strategic objectives which lead towards the siege as the offensive method of choice over the raid. States, with their need to control and administer territory (and the desire to get control of that territory with its farming population intact so that they can be forced to farm that land and then have their agricultural surplus extracted as taxes), aim to gain control of areas of agricultural production, in order to extract resources from them (both to enrich the elite and core of the state, but also to fund further military activity).

Thus, the goal in besieging a fortified settlement (be that, as would be likely in this early period, a fortified town or as later a castle) is generally to get control of the administrative center. Most of the economic activity prior to the industrial revolution is not in the city; rather the city’s value is that it is an economic and administrative hub. Controlling the city allows a state to control and extract from the countryside around the city, which is the real prize. Control here thus means setting up a stable civilian administration within the city which can in turn extract resources from the countryside; this may or may not require a permanent garrison of some sort, but it almost always requires the complete collapse of organized resistance in the city. Needless to say, setting up a stable civilian administration is not something one generally does by surprise, and so the siege has to aim for more durable control over the settlement. It also requires fairly complete control; if you control most of the town but, say, a group of defenders are still holding out in a citadel somewhere, that is going to make it very difficult to set up a stable administration which can extract resources.

Fortunately for potential defenders, a fortification system which can withstand a siege is almost always going to be sufficient to prevent a raid as well (because if you can’t beat it with months of preparatory work, you are certainly unlikely to be able to quickly and silently overcome it in just a few night hours except under extremely favorable conditions), though detection and observation are also very important in sieges. Nevertheless, we will actually see at various points fortification systems emerge from systems designed more to prevent the raid (or similar “surprise” assaults) rather than the siege (which is almost never delivered by surprise), so keeping both potential attacking methods in mind – the pounce-and-flee raid and the assault-and-stay siege – is going to be important.

As we are going to see, even fairly basic fortifications are going to mean that a siege attacker must either bring a large army to the target, or plan to stay at the target for a long time, or both. In a real sense, until very recently, this is what “conventional” agrarian armies were: siege delivery mechanisms. Operations in this context were mostly about resolving the difficult questions of how to get the siege (by which I mean the army that can execute the siege) to the fortified settlement (and administrative center) being targeted. Because siege-capable armies are either big or intend to stick around (or both), surprise is out of the window for these kinds of assaults, which in turn raises the possibility of being forced into a battle, either on the approach to the target or once you have laid siege to it.

It is that fact which then leads to all of the many considerations for how to win a battle, some of which we have discussed elsewhere. I do not want to get drawn off into the question of winning battles, but I do want to note here that the battle is, in this equation, a “second order” concern: merely an event which enables (or prohibits) a siege. As we’ll see, sieges are quite unpleasant things, so if a defender can not have a siege by virtue of a battle, it almost always makes sense to try that (there are some exceptions, but as a rule one does not submit to a siege if there are other choices), but the key thing here is that battles are fundamentally secondary in importance to the siege: the goal of the battle is merely to enable or prevent the siege. The siege, and the capture or non-capture of the town (with its role as an administrative center for the agricultural hinterland around it) is what matters.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part I: The Besieger’s Playbook”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-10-29.

October 5, 2024

Scary words of 2024 – “Luckily, FEMA is on the case”

As I recounted a few days back, I was relieved to hear from my friend in the Asheville NC area after the region absorbed the damage from Hurricane Helene. Tom Knighton had a similar experience:

A friend of mine lives at the edge of where Helene did her worst. He just got power back on yesterday and was finally able to let me know he was OK. I was worried for obvious reasons.

In the deepest, worst parts of where the storm ripped things to shreds, they’re trying to just make it to the next day. They’re struggling to find clean drinking water, food, shelter, the works.

Luckily, FEMA is on the case.

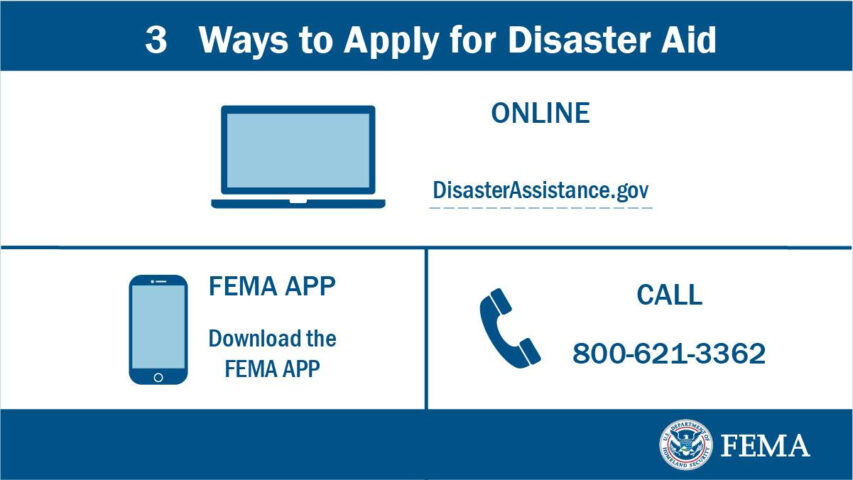

They took to social media yesterday and posted this crap.

That’s right. People who don’t have internet, phone service, or electricity should call, download an app, or log onto the FEMA website.

I won’t ask how stupid can the federal government be, but I’m worried they’d take it as a challenge.

Back in the day, FEMA would roll into a disaster area with paper applications and facilitate all of that right there. While the internet and smartphones are glorious things, this is a prime example of when they’re a terrible option for people.

Right now, American citizens are struggling. They’re thankful to be alive and are working their butts off to keep themselves alive. They’ve paid taxes their entire lives, and now that they need some of theirs back, their federal government is telling them to do what is physically impossible for many of them.

I can’t help but see this and think that their claims of having enough money in spite of spending hundreds of billions on illegal immigrants ring a tad hollow.

If they have the money, why not put boots on the ground getting people signed up for any assistance they may be entitled to?

Honestly, while I’ve commented before about the gross incompetence of the government in disaster response — and I’ll agree that maliciousness is most definitely a possibility, if not a probability in these instances — this is just weapons-grade … whatever, be it stupidity, meanness, or a combination of both.

Heads should roll.

Update: David Warren notes that it’s not merely FEMA incompetence, it’s active deterrence for private relief efforts by all federal agencies.

From the Internet (for instance updates from Elon Musk), we note that non-governmental charitable efforts are not merely “discouraged”. The government is seizing and impounding desperately-needed local goods and services. The rest of the federal bureaucracy is also “chipping in”, to stifle relief efforts. The FAA, for instance, is restricting private aircraft with supplies, and making it almost impossible to fly drones, demanding that flights be individually approved by their slothful trolls. Those who wish to bring help to the survivors have both the wreckage of the storm, and government agents to block them.

This is how things work in this world, and have worked, since the Reformation, when the state took over welfare, hospitals, schools, and all other eleemosynary institutions. Rather than allow inspiring expressions of Christian charity, they became the means for cynical political posturing and control. And with “democracy”, we have detailed laws and policies, to prevent the people from helping themselves — as they would do, by laws of nature.

September 29, 2024

This Bridge Should Have Been Closed Years Before It Collapsed

Practical Engineering

Published Jun 18, 2024Why Fern Hollow Bridge collapsed.

This is a crazy case study of how common sense can fall through the cracks of strained budgets and rigid oversight from federal, state, and city staff. And the lessons that came out of it aren’t just relevant to people who work on bridges. It’s a story of how numerous small mistakes by individuals can collectively lead to a tragedy.

(more…)

September 28, 2024

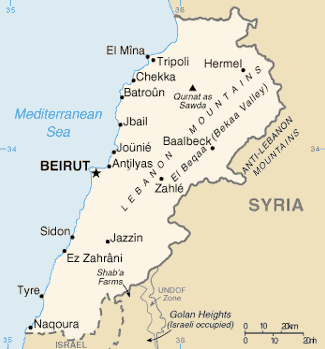

Lebanon is no longer a nation … it’s a parasitized husk operated by Iran’s proxies

In UnHerd, Tom McTague explains why there can be no “settlement” of the South Lebanon problem, because Lebanon ceased functioning as an independent state and is now largely controlled by Hezbollah, which means it’s indirectly controlled by Iran:

[…] A similar assessment was made about Lebanon, a country without a functioning state or economy and at the mercy of Iran’s colonial army, Hezbollah. This, also, was a situation that was thought to be containable — even as Iran exploited the anarchic chaos of Iraq and Syria to supply its proxy with enough weapons to devastate Israel.

The central conceit of the Abraham Accords was that, irrespective of Hamas, Hezbollah and the occupation of the West Bank, once the Israel-Saudi axis was formed, Iran could be pushed back and contained without direct American involvement. But, then, the depth of Hamas’s murderous brutality on 7 October shattered that assumption, leaving not only a traumatised and vulnerable Israel, but also a traumatised and vulnerable Western order forced to confront the stark realities of the Middle East.

Today, Lebanon is a dead state, eaten alive by Hezbollah’s parasitic power. The scale of the catastrophe in the country is hard to comprehend, much of it caused by the disruptive nature of Syria’s civil war. Since its neighbour’s descent into anarchic hell, some 1.5 million Syrians have sought refuge in Lebanon — a tiny country with a population of just 5 million. But, more fundamentally, with Hezbollah fighting to protect Bashar al Assad, the opposing countries — led by Saudi Arabia — began withdrawing funds from Lebanese banks. This sparked a financial crisis that left Lebanon with no money for fuel.

By spring 2020, the country had defaulted on its debts, sending it into a downward spiral which the World Bank in 2021 described as among “the top 10, possibly top three, most severe crises globally since the mid-nineteenth century”. Lebanon’s GDP plummeted by around a third, with poverty doubling from 42% to 82% in two years. At the same time, the country’s capital, Beirut, was hit by an extraordinary explosion at its port, leaving more than 300,000 homeless. By 2023 the IMF described the situation as “very dangerous” and the US was warning that the collapse of the Lebanese state was “a real possibility”.

With Iranian support, however, Hezbollah created a shadow economy almost entirely separate from this wider collapse. It could escape the energy shortages, while creating its own banks, supermarkets and electricity network. Hezbollah isn’t just a terrorist group. It is a state within a state, complete with a far more advanced army. “They may have plunged Lebanon into complete chaos, but they themselves are not chaotic at all,” as Carmit Valensi, from the Institute for National Security Studies at Tel Aviv University, told the Jerusalem Post.

Then came 7 October, after which Hezbollah tied its fate to that of the Palestinians, promising to bombard Israel with rockets until the war in Gaza was brought to a close. We have witnessed the frightening scale of its power over the past year, its bombardment forcing some 100,000 Israelis from their homes in Galilee to the safety of the Israeli heartlands around Tel Aviv. For the first time since modern Israel’s creation, the land where Jews are able to live in their own state has shrunk; the rockets are a daily reminder of the country’s extraordinary vulnerability, threatened on all sides by states who actively want it removed from the map — even from history itself. The pretence that the Palestinian and Lebanese questions could be contained, ignored or bypassed as part of a wider grand strategy to contain Iran has been shattered.

September 17, 2024

QotD: “Megacorporations” in history and fiction

I think it is worth stressing here, even in our age of massive mergers and (at least, before the pandemic) huge corporate profits, just how vast the gap in resources is between large states and the largest companies. The largest company by raw revenue in the world is Walmart; its gross revenue (before expenses) is around $525bn. Which sounds like a lot! Except that the tax revenue of its parent country, the United States, was $3.46 trillion (in 2019). Moreover, companies have to go through all sorts of expenses to generate that revenue (states, of course, have to go about collecting taxes, but that’s far cheaper; the IRS’s operating budget is $11.3bn, generating a staggering 300-fold return on investment); Walmart’s net income after the expenses of making that money is “only” $14.88bn. If Walmart focused every last penny of those returns into building a private army then after a few years of build-up, it might be able to retain a military force roughly on par with … the Netherlands ($12.1bn); the military behemoth that is Canada ($22.2bn US) would still be solidly out of reach. And that’s the largest company in the world!

And that data point brings us to our last point – and the one I think is most relevantly applicable for speculative fiction megacorporations – historical megacorporations (by which I mean “true” megacorps that took on major state functions over considerable territory, which is almost always what is meant in speculative fiction) are products of imperialism, produced by imperial states with limited state capacity “outsourcing” key functions of imperial rule to private entities. And that explains why it seems that, historically, megacorporations don’t dominate the states that spawn them: they are almost always products and administrative arms of those states and thus still strongly subordinate to them.

I think that incorporating that historical reality might actually create storytelling opportunities if authors are willing to break out of the (I think quite less plausible) paradigm of megacorporations dominating the largest and most powerful communities that appear so often in science fiction. What if, instead of a corporate-dominated Earth (or even a corp-dominated Near-Future USA), you set a story in a near-future developing country which finds itself under the heel of a megacorporation that is essentially an arm of a foreign government, much like the EIC and VOC? Of course that would mean leavening the anti-capitalist message implicit in the dystopian megacorporation with an equally skeptical take about the utility of state power (it has always struck me that while speculative fiction has spent decades warning about the dangers of capitalist-corporate-power, the destructive potential of state power continues to utterly dwarf the damage companies do. Which is not to say that corporations do no damage of course, only that they have orders of magnitude less capability – and proven track record – to do damage compared to strong states).

(And as an aside, I know you can make an argument that Cyberpunk 2077 does actually adopt this megacorporation-as-colonialism framing, but that’s simply not how the characters in the game world think about or describe Arasoka – the biggest megacorp – which, in any event, appears to have effectively absorbed its home-state anyway. Arasoka isn’t an agent of the Japanese government, it is rather a global state in its own right and according to the lore has effectively controlled its home government for almost a century by the time of the game.)

In any event, it seems worth noting that the megacorporation is not some strange entity that might emerge in the far future with some sort of odd and unpredictable structure, but instead is a historical model of imperial governance that has existed in the past and (one may quibble here with definitions) continues to exist in the present. And, frankly, the historical version of this unusual institution is both quite different from the dystopian warnings of speculative fiction, but also – I think – rather more interesting.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: January 1, 2021”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-01-01.

August 19, 2024

QotD: Government efficiency

Our greatest threat today comes from government’s involvement in things that are not government’s proper province. And in those things government has a magnificent record of failure.

Ronald Reagan, quoted in “Inside Ronald Reagan”, Reason, 1975-07.

August 9, 2024

A crisis of competence

Glenn “Instapundit” Reynolds on one of the biggest yet least recognized issues of most modern nations — our overall declining institutional competence:

Almost everywhere you look, we are in a crisis of institutional competence.

The Secret Service, whose failures in securing Trump’s Butler, PA speech are legendary and frankly hard to believe at this point, is one example. (Nor is the Butler event the Secret Service’s first embarrassment.)

The Navy, whose ships keep colliding and catching fire.

Major software vendor Crowdstrike, whose botched update shut down major computer systems around the world.

The United States government, which built entire floating harbors to support the D-Day invasion in Europe, but couldn’t build a workable floating pier in Gaza.

And of course, Boeing, whose Starliner spacecraft is stuck, apparently indefinitely, at the International Space Station. (Its crew’s six-day mission, now extended perhaps into 2025, is giving off real Gilligan’s Island energy.) At present, Starliner is clogging up a necessary docking point at the ISS, and they can’t even send Starliner back to Earth on its own because it lacks the necessary software to operate unmanned – even though an earlier build of Starliner did just that.

Then there are all the problems with Boeing’s airliners, literally too numerous to list here.

Roads and bridges take forever to be built or repaired, new airports are nearly unknown, and the Covid response was extraordinary for its combination of arrogant self-assurance and evident ineptitude.

These are not the only examples, of course, and readers can no doubt provide more (feel free to do so in the comments) but the question is, Why? Why are our institutions suffering from such widespread incompetence? Americans used to be known for “know how,” for a “can-do spirit”, for “Yankee ingenuity” and the like. Now? Not so much.

Americans in the old days were hardly perfect, of course. Once the Transcontinental Railroad was finished and the golden spike driven in Promontory, Utah, large parts of it had to be reconstructed for poor grading, defective track, etc. Transport planes full of American paratroopers were shot down during the invasion of Sicily by American ships, whose gunners somehow confused them for German bombers. But those were failures along the way to big successes, which is not so much the case today.

But if our ancestors mostly did better, it’s probably because they operated closer to the bone. One characteristic of most of our recent failures is that nobody gets fired. (Secret Service Director Kim Cheatle did resign, eventually, but nobody fired her, and I think heads should have rolled on down the line).

July 31, 2024

The Jasper wildfire – climate change or blatant government incompetence and neglect?

In The Line, Jen Gerson points out that the federal government had been given plenty of warning — literally years — about potentially serious problems near Jasper and had done nothing about them:

When Ken Hodges heard about the devastating wildfire that took out part of the historic mountain town of Jasper this week, he said he was “frustrated”.

“All I could say is that we tried to warn them that it was coming. We told them constantly. It’s not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when.”

The retired forester, along with his colleague Emile Begin, spent years repeatedly warning the parks service, the federal and provincial government, city council, and residents, that mis-management of the forests around Jasper had created a tinderbox that would inevitably spark a massive wildfire.

“I just feel so badly for the people who have lost their homes and their businesses. Could it have been prevented? I don’t know. If they had done everything they could have? Maybe. Something was going to happen over time, so it’s so frustrating and devastating.”

Hodges first spotted the problem almost a decade ago while skiing near Marmot Basin. From his years working in forestry in B.C. — a province that had previously been devastated by both wildfires and infestations of the Mountain Pine Beetle — Hodges was able to identify similar patterns of decay in the forests in Alberta.

“It was a hillside on the way up to Marmot that I looked up and thought ‘holy crap. The Mountain Pine Beetle is here.'” His experience told him exactly what would follow — fire.

Not just any fire. “It’s the intensity and the ferocity of the fire that can cause the problem. With climate change, that exacerbates the situation as well.”

Eventually Hodges connected with Begin. The two men between them had 40 years of experience in forestry in B.C. and Alberta, respectively. They feared the Parks service was not prepared for what the men had seen in B.C. — and told them so. Repeatedly. Vociferously. They also sent letters of warning to several ministers; they met with the local municipality. They were interviewed by the CBC for a story that was headlined “Jasper National Park not prepared for potential forest fire ‘catastrophe’, researchers say“.

That was in 2018.

Also in 2018, the pair issued an open letter that read: “The potential for a huge fire or mega fire is real. Fires of this type and magnitude generally occur in mid August to early September. With climate change it may occur earlier.”

The response?

“They just wrote us off,” Hodges told The Line this week.

July 16, 2024

Britain’s Tories – “It is hard to think of any political Party that has so relentlessly thrown away its political mandate”

Lorenzo Warby considers a few of the early lessons that can be drawn from the British general election results:

I dislike the term “the deep state”. It mystifies what is much more straightforward, even bland: how metastasising bureaucracy is undermining the resilience of Western societies and their political systems.

The British Labour Party has won a massive Parliamentary majority in the House of Commons even though its total votes fell: from 10,269,051 in 2019 — 32.1% of total votes — to 9,704,655 in 2024 — 33.7% of total votes. Labour’s massive Parliamentary majority is not a product of enthusiasm for Labour, but the fracturing of the votes of its opponents.

The Scottish National Party (SNP) vote fell dramatically — from 1,242,380 votes in 2019 to 724,758 in 2024. This was largely a casualty of the SNP embracing the genderwoo of Transactivism. Outside some narrow urban enclaves, no one votes for “woke” but, given a genuine opportunity, folk will vote against it. As Scots have.

The Liberal Democrats did very well, as they have a regionally concentrated vote — which, this time, they targeted properly — and disgruntled (posh) Shire Tories will protest vote Lib-Dem. Clearly, lots did.

The Tories did so badly because their already low vote was further reduced by the Reform vote surge. The Reform vote represented voters punishing the Tories for their failure to do anything they had promised. As political scientist Matt Goodwin puts it:

They failed to control our borders.

They failed to lower legal immigration.

They failed to cut taxes and the size of the state.

They failed to take on woke, exposing our children to ideas with no basis in science.

And they failed to level-up the left behind regions.

It is hard to think of any political Party that has so relentlessly thrown away its political mandate.

So, an angry, unhappy electorate (rightfully) punished two governing Parties (Tories and SNP) and has given Labour a massive majority, with little enthusiasm — almost two-thirds of voters voted for someone else — on a relatively low turnout.

There is, however, a deeper institutional issue underlying these results. Why are voters so disgruntled? Why did the Tories fail so spectacularly?

The answer to these questions is a mixture of how institutions have evolved, the development of media culture, the Anywhere-Somewhere divide and technocratic delusions.

Technocratic delusion

The technocratic delusion is multi-layered. It holds that governing is a managerial input-output problem, government bureaucracy simply implements policy, and that politics is not a motivation and coordination problem.

None of these presumptions are true, so technocratic politics fails. It does not connect to voters and does not understand, or grapple with, the actual institutional landscape.

The technocratic delusion is a way for clever people to be spectacularly clueless. Not the only such mechanism in the modern world.

June 16, 2024

“What the hell is going on in Canada?”

If you’re not Canadian or have any Canadian friends, you may not understand just how badly broken the country is — and the federal government is still desperately pretending that we’re all onboard with the Net Zero/Carbon Tax/”you’ll own nothing” bullshit and piling on the long-term debt:

One of Canada’s intelligence agencies, a couple of months ago, sent a memo to the Liberal federal government informing them that, in the near-future years to come, they are worried about revolutionary activity. I believe Canada is a good case study because it seems the country has been a sociological testing ground for the powers that be to see what happens. Canada is a surreal twilight zone where it feels like every psyop known to man is hurled its way. Canada unquestionably has the worst demographic and immigration issues, the worst housing issues, the worst social stability, and upwards mobility issues, all adjusted and proportional to its population and size, of course. For our purposes, I believe Canada serves as the worst-case scenario of how bad the dating market can be, and how bad it will continue to get.

Canada has some of the lowest upward social mobility among developed nations, especially for young people, particularly within the OECD and G8. This means that young people in Canada find it relatively difficult to move up the economic ladder compared to their parents.

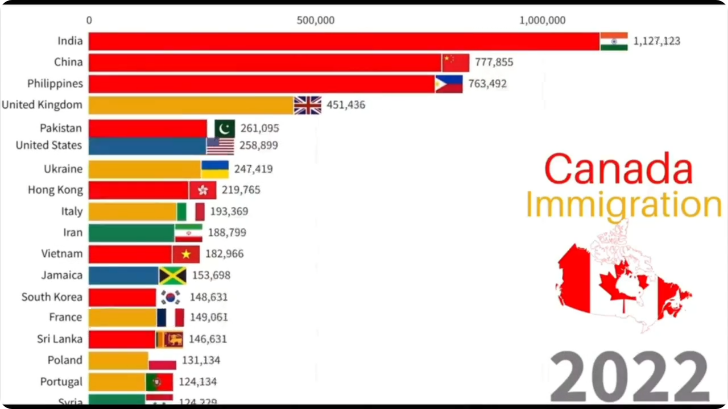

In 2022, Canada’s population growth was significantly driven by immigration. According to Statistics Canada, approximately 95% of the population growth in that year was attributed to immigration. This includes both permanent and temporary residents, with a notable influx of international students, temporary workers, and permanent residents. Only a meagre 5% of Canada’s population growth, including recent immigrants, was from organic growth and childbirth. Below are the national origins of immigrants over the last twenty-four years. The combined total number of people entering Canada per year, including international students, temporary foreign workers, legal immigrants, and refugee claimants, is approximately 1,133,770 individuals officially. In reality, the government over the last four years has lost count.

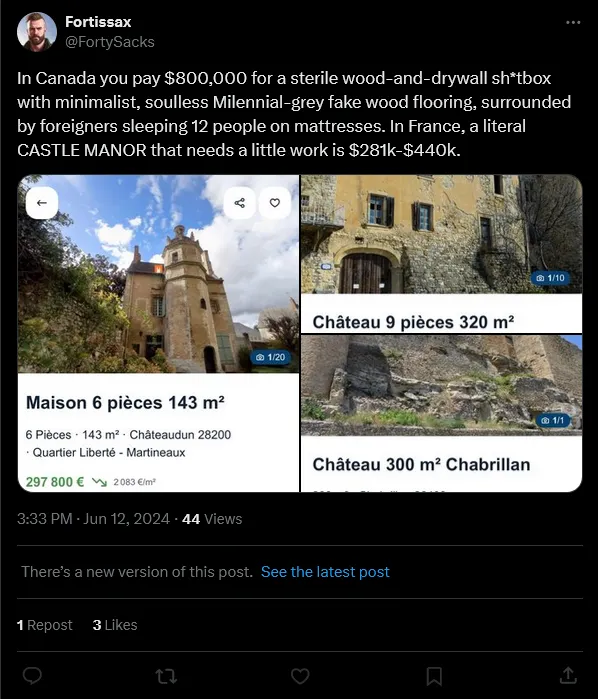

As of April 2024, the average home price in Canada is approximately CAD $703,446. This is €477,121.93 and USD $511,466.93. Would you like to see what $703k CAD can get you in France? Hint: a lot more than in Canada.

This has been noticed so much by Canadians that it is now a meme, with Conservative Party and opposition leader Pierre Poilievre pointing it out in the House of Commons. You can compare the price of homes and the cost of living with Canadian wages. You can also compare how far those meagre wages would go in other first-world countries like France, Germany, or Sweden. The answer is much farther. Much, much farther. There is currently no hope, short of radical action by the government unheard of in Canadian history, for this situation to be rectified. The only other option is best left unsaid.

“Educated” Women Lead

In Canada, among ethnic Canadians, a significant portion of the female population is more educated and makes more money than Canadian men. Canadian men make, on average, CAD $48,500, while women make CAD $42,000. However, only 56% of men have post-secondary education, while 68% of women do. Men have completed higher levels of high school, and women have completed higher levels of college or university. This has led to a massive gap in socioeconomic status between men and women. It gets worse when you include non-ethnic Canadians. Completed levels of post-secondary education for men remain at 56%, while women’s rise to 73%.

We know that in our post-industrial world, resources translate to money. Money and completed levels of education translate to status. Women are 50% more likely to divorce men when they make more money. When women are already the initiators of divorce 70% of the time, it starts looking pretty ugly, fast.

April 14, 2024

More evidence of Canada’s dwindling state capacity – not enough judges

Matt Gurney discussed this issue along with several others in this week’s Line podcast (highly recommended listening/watching, by the way):

Superior Court of Justice building on University Avenue in Toronto (formerly the York County Court House).

An evolving line of defence we see from the federal Liberals is that they’re actually doing a great job. It’s those darned provincial premiers that are screwing things up.

We touched on this in our last dispatch. And you know what? There’s some truth to it. Some, I stress. A lot of issues that are much vexing Canadians today aren’t fully or even primarily in federal jurisdiction. Health care and housing are two obvious examples. Canada is a complicated place, and the Liberals no doubt prefer to not talk about things that they’ve done that have exacerbated challenges faced by other orders of government. But the basic point is fair: Justin Trudeau ain’t to blame for all that ails you. Or at least, the blame ought to be spread around some.

This national disgrace, though, lands squarely on him.

You might have read about the shortage of judges across the country. It’s a pretty niche issue, so you might have missed it. Even if you’ve heard about it, you may not have paid much attention to it. Most Canadians won’t have much contact with the criminal justice system over their lives, let alone make their careers in it. But the crux of the issue is this: appointing judges to provincial superior courts, where many of the most serious matters are heard, is in the federal jurisdiction. Solely. Ditto appointments to the courts of appeal: totally in the federal jurisdiction. And the feds have fallen way behind on filling vacancies and aren’t appointing judges fast enough to erase the backlog. Despite a spate of recent appointments, there are dozens of vacancies across the country. These are funded positions that ought to be filled and overseeing cases. But they aren’t, entirely because the feds haven’t made the necessary appointments. That’s the issue.

A lack of judges is creating bottlenecks in the justice system. Arrests are being made and charges are being laid and cases are being prepared and then … nothing happens. Because you can’t hold a trial if there isn’t a judge available to oversee it.

The Toronto Star‘s Jacques Gallant has established something of a bleak speciality in his recent reporting. He’s written a series of articles in recent months documenting serious criminal cases that are being thrown out of court, with the accused set free, because their trial has been delayed so much that it cannot be completed before the Supreme Court-ordered limit for a “reasonable” wait for a trial runs out. That’s 18 months for more minor issues, and 30 months for serious ones.

To be clear: the decision to throw out the cases is, in a legal sense, correct. Indeed, it’s mandatory. The Supreme Court determined what a hard limit should be, and a case that exceeds that is dead. Full stop. That’s the law of the land. The judges forced to preside over these dismissals are not to blame, and are increasingly venting their frustration in their rulings. They’re mortified, and they’re criticizing the government in unusually blunt terms, to put it mildly. You don’t often read court rulings that come off more like op-eds, but we live in weird times.

But it’s a good thing that they’re saying something. Because these vacancies are having appalling real-world consequences. Gallant wrote recently about a case that I felt would mark the low point in the entire embarrassment. A woman had accused a man of raping her. She did a brave thing and reported it. The police believed her and made an arrest. The Crown reviewed the evidence and believed her, and proceeded with a trial. A jury believed her, and after considering the evidence against the accused and hearing his defence, convicted him of the crime.

And then the judge tossed the case, setting aside the verdict and letting the accused go free, innocent in the eyes of the law. Because the clock had run out.