seangabb

Published 5 Feb 2021[Update 2023-03-02 – Dr. Gabb took down the original posts and re-uploaded them.]

Here is the second lecture, which describes the vindictive treatment of Hannibal and Carthage, and explains this in terms of how the Second Punic War destabilised both Italy and the Roman Constutition. Between January and March 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

February 16, 2022

Roman Republic to Empire 02 The Carthaginian Curse

February 8, 2022

Roman Republic to Empire: 01 Mistress of the Mediterranean

seangabb

Published 21 Jan 2021[Update 2023-03-02 – Dr. Gabb took down the original posts and re-uploaded them.]

In 120 BC, Rome was a republic with touches of democracy. A century later, it was a divine right military dictatorship. Between January and March 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

November 1, 2021

QotD: Latin

Any English speaker who calls Latin easy is either a genius or a fool. It is a synthetic Indo-European language that communicates in ways very different from English. Nouns are divided into at least five classes, each of which has five or six or seven cases – singular and plural – to express meanings that we express by adding prepositions. Pronouns have their own declensions. Except for the perfect passive tenses, verbs are generally inflected. Because the Classical grammar is a snapshot of a language in rapid and profound change, there are duplications and irregularities everywhere. The future tense, in particular, is broken, and has been reconstructed in every language I know that descends from Latin. Add to this an elaborate syntax, an indifference to what we regard as a normal order of words, and a vocabulary that is naturally poor, but expanded by allowing most common words to bear different meanings that must usually be inferred from their context.

This being said, anyone who denies the language is worth learning is a barbarian who deserves to live in the illiterate swamp that we nowadays call civilisation. Without denying the importance of the Greeks, Rome stands at the origin of our literature and law and religion. Latin was, until the late seventeenth century, the normal language of learning and international communication. Directly or indirectly, Latin has given English around sixty per cent of its words. I am not sure if anyone can write English well who is ignorant of Latin. I do not believe anyone can appreciate or notice the full register of our own classical literature without some knowledge of Latin. A further point is that, even today, a qualification in Latin is taken as proof of general intelligence. In short, Latin is a struggle, but a struggle worth undertaking.

Sean Gabb, “A Review of Latin Stories (2018)”, Sean Gabb, 2018-12-23.

September 30, 2021

Petrol shortages in the UK

I’ve seen several reports on the somewhat sudden rash of petrol (gasoline to US/Canadian readers) shortages in Britain, and most of those reports airily pin the blame for the situation on Brexit. To the media, Brexit seems to be an all-purpose explanation for anything that goes wrong (in the same way that previous administrations get the blame for current problems even many years after they left power). Sean Gabb says that despite the frequent glib blaming of Brexit, in this case it is part of the reason:

There is in the United Kingdom a shortage of lorry drivers. This means a dislocation of much economic activity. Because it cannot be delivered, there is no petrol in the filling stations. Because there are not enough drivers, and a shortage of fuel, we may soon have shortages of food in the shops. Christmas this year may not involve its usual material abundance.

These difficulties are wholly an effect of the new political economy that has emerged in England and in many other Western countries since about 1980. An army of managers, of agents, of administrators, of consultants and advisers and trainers, and of other middle class parasites has appropriated a growing share of the national income. This has happened with at least the active connivance of the rich and the powerful. Since, in the short term, the distribution of the national income is a zero-sum game, the necessary result is low and falling real wages for those who actually produce. So long as the productive classes can be kept up by immigration from countries where even lower wages are on offer, the system will remain stable. Because leaving the European Union has reduced the supply of cheap labour, the system is no longer stable in England.

There are two obvious solutions. The first is to rearrange the distribution of income, to make the productive classes more able and more willing to produce. Since this would mean reducing the numbers or incomes or both of the parasite classes, the second is the solution we mostly read about in the newspapers. This is to restore the flow of cheap foreign labour.

In summary, that is my explanation of what is happening. For those who are interested, I will now explain at greater length. According to the mainstream theory of wages, labour is a commodity. Though workers are human beings, the labour they supply to employers is of the same general nature as machine tools and copper wire and cash registers and whatever else is bought and sold in the markets for producer goods. A wage therefore is a price, and we can illustrate the formation of wage rates with the same supply and demand diagrams as we use for illustrating the formation of prices:

The supply curve slopes upwards because most work is a nuisance. Every hour of labour supplied is an hour that cannot be spent doing something more enjoyable. Beyond a certain level, workers can only be persuaded to supply more labour if more money is offered for each additional hour of labour. As with other producer goods, the shape of the demand curve is determined both by the price of what labour can be used to produce and by the law of diminishing returns.

[…]

Our problem in England is that large areas of economic activity have been rigged. There is an immensely large state sector, paid for by taxes on the productive. Most formally private activity is engrossed by large organisations that are able to be so large either because of limited liability laws or by regulations that only large organisations can obey. The result is that wages are often determined less by market forces than by administrative choice. In this kind of rigged market, we cannot explain the distribution of income as a matter of continual choice between marginal increments of competing inputs until the whole has been distributed. It may be better to look at a modified wages fund theory. A large organisation has a pot of money left over from the sale of whatever its product may be, minus payments to outside suppliers, and minus whatever the directors choose to classify as profit. This is then distributed according to the free choice of the directors, or how hard they can be pushed. Or we can keep the mainstream cross-diagrams, but accept that the demand curve is determined less by marginal productivity than by the overall prejudices of those in charge.

Therefore the growth of a large and unproductive middle class, and the screwing down of all other wages to pay for this. This is not inevitable in rigged markets, but is possible. It has come about since the 1980s for three reasons:

First, the otherwise unemployable products of an expanded higher education sector have used all possible means to get nice jobs for themselves and their friends;

Second, the rich and the powerful have accommodated this because higher wages and greater security for the productive might encourage them to become as assertive as they were before the 1980s;

Third, that these rich and powerful see the parasite classes as a useful transmitter of their own political and moral prejudices.

August 9, 2021

July 6, 2021

Conspiracies within conspiracies within conspiracies

In the latest edition of the Libertarian Enterprise, Sean Gabb considers the evolving nature of Wuhan Coronavirus conspiracy theories:

“Covid 19 Masks” by baldeaglebluff is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

We have, for the past eighteen months, lived through a fantasy pandemic. If unpleasant, the Virus is not particularly deadly. The number of cases is a product of testing, the number of deaths a statistical fraud. We have had much worse infections in living memory. We never responded to those by locking down whole populations and making hysterical fear an object of state policy. What is happening?

The most likely answer is stupidity. The quality of the people who rule Britain and America has dropped through the floor since about 1990, and it was not that high then. Sadly, though, the rest of the world still believes Britain and America are the pinnacle of civilisation, and so, whatever madness is decided in London and Washington is copied without question almost everywhere else. Take stupidity, add short-term advantage to the usual suspects in politics and business, and we have the Coronavirus Panic.

But arguments from stupidity are boring. They are the equivalent of denying the existence of ghosts and second sight — worthy and true, but unentertaining. Much better is to begin from the assumption that the idiots in charge are not really in charge, but are only front men for the supremely intelligent and supremely effective and supremely wicked Ones-on-High. Do this, and explaining the panic becomes an argument over which conspiracy theory best fits the observed facts.

Until a few weeks ago, my favourite was that the Virus was a bioweapon that had somehow leaked from a Chinese laboratory. It was spotted by the main governments, because they were all working in secret on something similar. This would explain the initial panic. As for the piffling number of deaths, bioweapons are still at the experimental stage, and no one realised until it was too late that modified viruses lose their potency almost at once in the wild. This was my favourite conspiracy theory for over a year. I only went off it when the authorities stopped denouncing it and punishing anyone important who said it was true, and instead announced on television that it might be true. Since the hacks in the mainstream media are just bright enough not to tell the truth even by accident, it was half a minute to give up on a year of enjoyable speculation.

There are other conspiracy theories. Regrettably, most of these border on the respectable. For example, the panic is a cover for clawing back some of the manufacturing outsourced to China since the 1990s. Or it is an excuse for ending the unwise monetary policies of the past decade and inflating away the resulting national debts. These all have an appearance of the probable, and are therefore dull before the first paragraph is read. But, looming over all the others, is the merger of scepticism about vaccines and the Agenda 21 conspiracy.

For those unaware of it, Agenda 21 is boring drivel from the United Nations about not cutting down trees. Behind this, though, is an alleged conspiracy to reduce the human population from seven billion to half a billion. Doing this, apparently, will end all the fanciful scares about global warming, and leave the lucky survivors free to use all the electricity they want without feeling guilty.

The latest version of this theory is that the Virus is a fraud, but justifies injecting people with a vaccine that will make most of them fall down dead, or in some degree sterilise them. There are passionate advocates of the revised theory, all of them begging us to keep away from any of the vaccines on offer. I have so far kept away from the vaccines.

May 24, 2021

“The revolution will be defeated when people stop being scared”

Sean Gabb discusses some outrageous elements of the ongoing cultural revolution against freedom of speech in Britain, the United States and many other western nations:

David Hume Tower at the University of Edinburgh (listed building number 50189).

Photo by Enric via Wikimedia Commons.

If I am a self-employed plumber or electrician, I can speak my mind and laugh at the complaints. If, like the great majority in this country, I am a salaried employee — whether in the state or private sectors is unimportant: the pressures to conformity are the same in both sectors — I must be careful what I say. I am scared of the sack. I am scared of sudden redundancy. I am scared of missing out on promotions. I am scared of generally unfair treatment because of my opinions. I therefore hide my opinions. The Peter Tatchells among us then look round complacently, telling themselves and each other that silence equals agreement, and that the few squeaks of opposition are from “disreputable extremists.”

This explains the present unbalanced debates over slavery and colonialism. Take these examples:

- First, in September 2020, the David Hume Tower at Edinburgh University was “denamed”. Someone had bothered to read the 1748 essay “Of National Characters”, and found in one of its footnotes an unfashionable statement about race. It was at once set aside that Hume was a philosopher of at least considerable note. More important was the “non-overt disrespect, offence, and racism that Black students have to go through at the University of Edinburgh”.

- Second, the Music Department at Oxford is presently worried that its curriculum “structurally centres white European music”, and that this causes “students of colour great distress”. It therefore wants to change its focus from the European classical tradition to things like “Artists Demanding Trump Stop Using Their Songs”. It also wants to discourage students from studying musical notation, as this is a “colonialist representational system”.

I could give a third illustration, and a fourth. I could fill a pamphlet with more. Some would be more alarming, though few less absurd. But these two can stand well enough for all the others. What makes these debates so irritating is that they are not debates. One side can put its case just as it pleases. The other is reduced to accepting all the main charges and begging for mitigation: “What Hume said was evil and unpardonable — but he was important for other things.” Or: “I feel your pain, but Mozart owned no slaves, and everyone knows that Beethoven was really black.” Because it has been so humbly begged, full mitigation will, in both cases, be granted. Hume will continue to be studied in the universities. Music students at Oxford will continue to use the standard notation and to analyse the usual classics. But preventing these things was never part of the agenda. The agenda was and is to transform what were honoured or unquestioned parts of our civilisation into things useful but more or less suspect, things subject to a toleration that may be varied or withdrawn at any time without notice.

It should be plain that we are, in both England and America, living through a revolution. This is not a normal revolution as these things are considered. Unlike in France or Russia, there has been no overthrow of an established order, no burst of state violence, no establishment after that of an overtly new order. There are no secret police. There are no labour camps. No one is beaten to death in a police cell. All the same, we are living through a revolution. It is a revolution that has involved the gradual capture of education, the media, the administration, the charities and the more permeable religious institutions, and the recent aligning of the larger or more glamorous business concerns. I see no point in discussing its ultimate objects. I am not sure if these are wholly agreed. But its provisional object is the destruction of our traditional identity, and of our liberty so far as this stands in the way of that provisional object.

These two elements of the provisional object are equally important. Our civilisation is being pulled apart because doing so strips away the mass of associations that, left in place, might hold up the more alarming parts of the transformation. Opposition is so feeble not only because that is all that will be tolerated: feeble opposition is all that can be tolerated. This is a revolution in which opponents are not murdered, but only scared into silence. They are scared into silence chiefly by fear of destroyed or blighted careers. The revolution will be defeated when people stop being scared. Then, there will be vicious and unrelenting public mockery, and commercial boycotts, and shareholder rebellions, and lost elections, and the general feeling of solidarity and impunity still sometimes found in a football stadium.

January 3, 2021

QotD: Literary stasis in the Byzantine empire

Undoubtedly, the Mediaeval Romans – now exclusively Greek in their language – made little effort to be original in their literature. They had virtually the whole body of Classical Greek literature in their libraries and in their heads. For them, this was both a wonderful possession and a fetter on the imagination. It was in their language, and not in their language. Any educated person could understand it. But the language had moved on – changes of pronunciation and dynamics and vocabulary. The classics were the accepted model for composition. But to write like the ancients was furiously hard. Imagine a world in which we spoke Standard English, but felt compelled, for everything above a short e-mail, to write in the language of Shakespeare and the Authorised Version of the Bible. Some of us might manage a good pastiche. Most of us would simply memorise the whole of the Bible, and, overlooking its actual content, write by adapting and rearranging remembered clauses. It would encourage an original literature. Because Latin soon became a completely foreign language in the West – and because we in England were so barbarous, we had to write in our own language – Western Mediaeval literature is often a fine thing. The Mediaeval Romans never had a dark age in our sense. Their historians in the fifteenth century wrote up the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in the same language as Thucydides. Poor Greeks.

Sean Gabb, “The Mediaeval Roman Empire: An Unlikely Emergence and Survival”, SeanGabb.co.uk, 2018-09-14.

November 30, 2020

September 29, 2020

Was it actually a “Plandemic”?

Sean Gabb recently published a collection of essays written during the lockdown for Wuhan Coronavirus. This excerpt is from the introduction to “Plandemic” or The Hand of God?:

My general argument is that the Coronavirus Panic should be divided under two headings. The first is the Virus itself as a medical fact and the immediate responses. The second is a set of changes already evident and sometimes advanced before the March of 2020, but that have now been greatly accelerated. Of these, the second is by far the more important. The first, even so, is of interest in its own right.

The Virus has not been all that we were told it would be. Last March, much of the world was ordered into indefinite lockdown on the grounds that we faced the greatest pandemic since the Spanish Flu of a century ago. For weeks in my own country, the BBC filled the television screens with statements by scared, sweating politicians, and lifted all restraint from its own hyperventilating staff. Now, as I write in the middle of September, we can be sure that it killed no more people than a seasonal influenza, and that most of its victims were very old or had been already weakened by some other condition. We can be sure it killed no more than seasonal influenza. Given the questionable definition of Coronavirus deaths, it may have killed many fewer.

I know that pandemic infections often come in several waves, and second waves can be more deadly than the first. But the second wave we are now said to be entering is evidenced by infections rather than deaths, and these infections are counted and published in ways more questionable than the counting and publishing of the earlier alleged deaths. I do not know what will have happened by Christmas. I suspect, however, that nothing much will have happened.

I have no fixed idea of what caused the panic. I am told that the Coronavirus was a bioweapon that escaped from a government laboratory. If it was, I can imagine that political leaders all across the world were taken aside by their own scientists, who were working on something similar, and told of the coming apocalypse. I lack the scientific understanding to judge the truth of this claim. But, if true, it would explain the panic. It would also justify the panic, so far as no one might have known for sure how infectious and how deadly this bioweapon was.

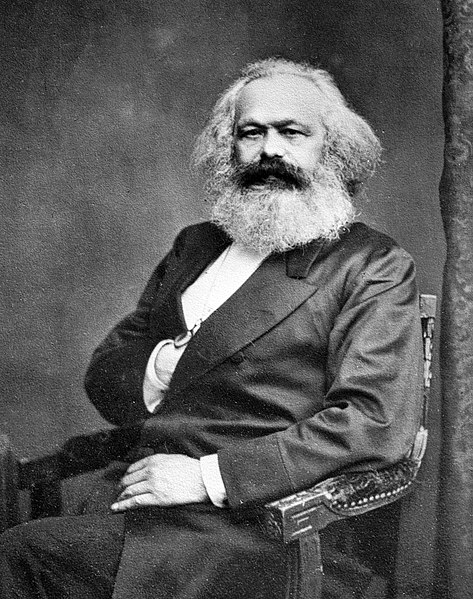

I am more inclined, though, to believe that the panic was a universal hysteria just waiting to be realised. The world at the beginning of this year was in a similar moral state to the world in 1914. There had been a generation of rising prosperity and of rising discontent. Some groups had benefitted out of proportion to their numbers and believed merit. If only relatively, others had fallen behind. Some believed the progress had not been fast enough, and that it could be hastened by various institutional changes, others that it was bad in its effects, and that it should be at least slowed. In 1914, all these discordant energies were channelled – both by deliberate policy and by popular enthusiasm – into a catastrophic war. This year, they found their outlet in the Coronavirus. Since I am making the same point, I might as well quote Marx:

Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

I will only add that, on the real stage of world affairs, farce is always preferable to tragedy. Facemasks are better than gasmasks. Better the statistical mirage of last spring than the genuine casualties of Verdun and the Somme.

September 16, 2020

Lockdown justification theories

In the most recent Libertarian Enterprise, Sean Gabb reports on a demonstration last month in London organized by Piers Corbyn which resulted in Corbyn being almost instantly fined £10,000 despite other, larger and more violent demonstrations not drawing any kind of judicial sanctions:

David Icke about to speak at Piers Corbyn’s 20 August anti-masking demonstration in Trafalgar Square.

Screencap from YouTube video – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DOZQ58uTWdw

The consensus at the demonstration appears to have been that the Coronavirus is some kind of fraud, and that the laws to stop its spread are really intended to carry us into a nightmarish New World Order tyranny. I disagree with this view. I believe instead that, looking back from one or two years, the Coronavirus Panic will be seen as a disaster for at least the British ruling class, and as somewhere between a blessing and nothing very bad for the majority of everyone else.

For the avoidance of doubt, I have no belief in the goodness of our ruling class. The Labour Party represents a new and hegemonic Establishment. The project of this Establishment is to bring about changes that are meant to be fatal to the traditional peoples of my country, and that will not be to the advantage of the groups they are supposed to raise up. Whether this project is evil or deluded is beside my present point, though it is probably something of both. There are two possible views of the Conservative Party. It may be worth supporting because, though willing to see it roll forward of its own momentum, the leaders do not want to hurry the project forward, but are mainly interested in personal enrichment. Or it may be a Potemkin opposition — gathering votes from the discontented, while self-consciously making sure those votes are wasted. Again, the exact truth is beside my present point. What does matter is that we go into every election less free and less at home in our country than at the previous election.

This being admitted, there is a loose connection between me and the speakers and attendees at Mr Corbyn’s demonstration. At the same time, there is a difference between cynicism and paranoia. As a cynic, I do not believe that everything untoward that happens is there to hurry the project of change. I do not believe that our ruling class is in charge of everything. I do not believe that it understands everything. Whatever its origin, the Coronavirus appears to have driven our various rulers into a genuine panic. Yes, Boris Johnson is a fool, and there is an army of the powerful who wanted an excuse to stop our final departure from the European Union. Yes, the Democrats were looking to upstage Donald Trump in time for the next American election. But this has not been a panic in just two countries. The Japanese cancelled their Olympic Games — losing them for the second time in eighty years. The Chinese brought four decades of economic growth to an end. The Indians and South Africans panicked. So did most of the Europeans. The panic was joined by ruling classes with no visible interest in putting the dreams of the Frankfurt School into practice.

Focussing on my own country, what ruling class institution has benefitted from the Coronavirus Panic? Look beyond the propaganda, and it is plain that the response of the National Health Service was a disgrace. Myriads of diagnoses and treatments were cancelled without good reason. We still have no dentistry. The public sector as a whole went on paid leave for six months. The schools closed and the teachers vanished — no great loss there, of course. Even if none goes bankrupt, dozens of universities will need to downsize — no loss there either. The police behaved throughout like fascist goons. Every institution set up or adapted to advance the project of change has emerged from the past six months revealed as broken and covered in ridicule. What sort of a planned crisis is it that ends in magnified cynicism and in paranoia that can fill Trafalgar Square on a Bank Holiday weekend? The general mood in this country is approaching what you see at the end of a lost war.

Or what associated commercial interests have benefitted? The politicised entertainment media is flat on its back. The commercial property sector is entering a melt-down. House prices in all the nice parts of London are going into a downward spiral. Public finances will be squeezed for years to come; and, given a choice between projects of change and a liveable dole, the electors are likely to make their wishes undeniable. Globalised patterns of trade have been disrupted, raising question marks over all the presiding global institutions. The last thing financial services needed was another big shock. As for the commercial beneficiaries, these are libertarian by default. For all that can be said against them, Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg have opened the media to anyone who knows how to use a computer keyboard. Their turn to corporate censorship has, at every step, been a response to outside pressure. Every one of these turns has been half-hearted and driven by a natural, if not always creditable, desire to continue growing richer. There is no particular benefit for the American and British ruling classes if Mr Bezos becomes a trillionaire and Richard Branson ceases to be a billionaire.

On a related note, Jay Currie points out that the media’s current laser-intense focus on reporting Wuhan Coronavirus cases allows the narrative to continue relatively undisturbed and which might be totally overthrown if they reported instead on deaths from the Chinese Batflu (H/T to David Warren for that useful epithet):

In the UK, France, Ontario and various other jurisdictions COVID case counts have risen at an alarming rate in the past few weeks. Unfortunately, mandatory masking and strict lockdowns seem to be the only tools governments feel they have in the face of case count surges.

It can be argued that the increasing case counts may be an artifact of more testing. Or a product of the sensitivity of the tests themselves; but the actual case numbers keep going up.

Our media, God bless them, at a national level seem to be entirely focused on case counts to the point where, in this CBC story on Ontario’s numbers, there is simply no mention of the “death count”.

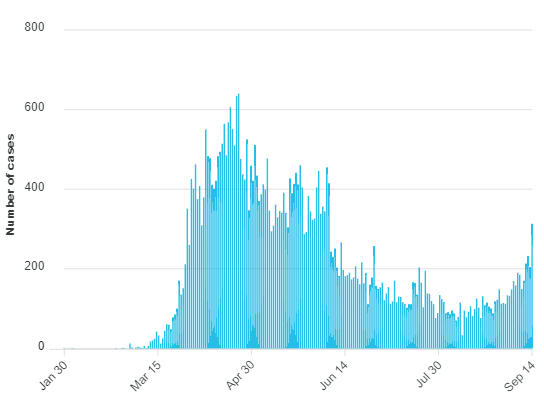

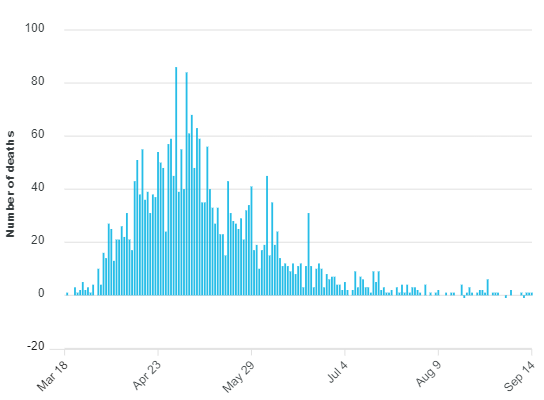

Why could this be? Well, take a look at these two graphs from Ontario:

If you look at the top graph the sky is falling and masks, social distance, lockdowns, school closures and “stay at home” all make a lot of sense. If you look at the bottom graph, COVID is over.

In Montreal over this last weekend up to 100,000 people marched against mandatory masks. The mainstream media downplayed the turnout and suggested that there were all sorts of conspiracy theorists, Qanon believers, far right and Trump supporters marching. There probably were. But I suspect the vast majority of the marchers were responding to the disproportionate response of the Quebec government to graphs which look very much like Ontario’s.

People are more than willing to go along with governmental measures they can see the point of. “14 days to flatten the curve and prevent hospitals from being overwhelmed” made sense back in April. And the measures taken then may well have worked. But it is mid-September and the hospitals and their ICUs are not even slightly overtaxed.

June 30, 2020

May 26, 2020

“No more pencils, no more books…”

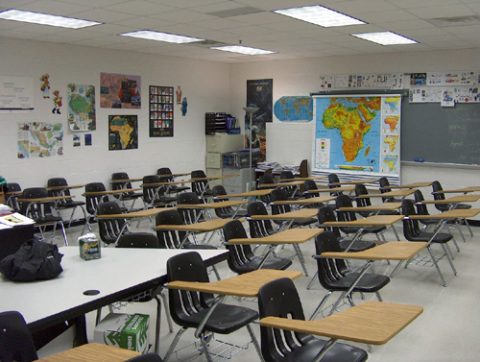

In the latest edition of the Libertarian Enterprise, Sean Gabb considers the demands from the British government to quickly re-open the schools over the concerns of the educational unions and administrations:

The latest turn in an increasingly dull coverage of the Coronavirus panic is a proposed reopening of the schools. The Government wants them open as soon as possible for at least some of their students. The teaching unions are bleating that no one should go back until their members can be sure of not catching anything. The headmasters are worried about compliance with the social distancing rules. As a conservative of sorts, I think I am supposed to side with the Government and the pro-Conservative journalists — denouncing the teachers as a pack of idlers where not cowards, and insisting that those factories of essential skills must be set back in full production before the summer holidays. Of course, my settled view as a libertarian is that the teaching unions deserve all the support I have never so far given them. The schools must remain closed until no one is in any danger of so much as an attack of hay fever. The schools have been largely closed since the end of March. The longer they stay largely closed, the better. Best of all if they never reopen — or never reopen as they have been since attendance was made compulsory at the end of the nineteenth century.

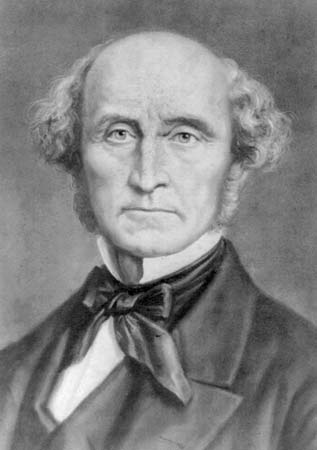

I quote John Stuart Mill on compulsory schooling:

A general State education is a mere contrivance for moulding people to be exactly like one another: and as the mould in which it casts them is that which pleases the predominant power in the government, whether this be a monarch, a priesthood, an aristocracy, or the majority of the existing generation; in proportion as it is efficient and successful, it establishes a despotism over the mind, leading by natural tendency to one over the body.

(On Liberty, 1859, Chapter 5, “Applications.”)This has always been the case in some degree. The spread of state schooling in England after 1870, and particularly after it was made compulsory in 1880, and then extended in 1902, is probably inseparable from the nationalist hysteria that drove our participation in the Great War. It also may explain the perverse belief, general until the 1970s, in the unique goodness and honesty of our ruling class. This being said, reasonable patriotism is to be encouraged; and, compared with others, our ruling class was not until recently so bad. A further point is that compulsory state schooling used to be reasonably effective at giving the mass of people a basic education. By 1960, most people were literate and numerate. They could spell and write grammatical prose. They had some exposure to the English classics, and the means of exploring these to greater depth if they wished. They had some understanding of history and the sciences. You can tell much about the quality of a people by examining what is read and watched. Looking at the popular arts in England during much of the twentieth century explains why this passage in On Liberty was less often discussed than his arguments for freedom of speech. Mill was right in the abstract. He could be shown to be right in certain particulars. But the evils of compulsory state schooling were mostly potential.

All this, however, is in the past. Since about 1980, schooling of all kinds has been made into a concerted means of indoctrination. The cultural leftists have captured both the classrooms and the curriculum. I will not elaborate on this claim. Some will argue over terminology, some over the merits of the capture, but hardly anyone denies the broad fact. One of the main functions of modern schooling is to bring about and to protect a radical departure from the old intellectual culture of this country.

Much of this departure has been achieved by preaching in the classroom. But it is supplemented by a growing bureaucracy of surveillance. The teachers themselves are watched, and they can be punished for dissenting from the established discourse. There is, for example, the Government’s Prevent strategy, which applies to the whole state machinery. Its purpose is to identify and root out anyone defined as a “political extremist.” Anyone identified as such is effectively banned from working with children and young people, and probably in the state sector as a whole.

May 19, 2020

Some changes to the working world … when the world gets back to working

Sean Gabb has some thoughts on the post-lockdown return so … well, not normal, but as the economy reaches toward a new working equilibrium:

Kensington High Street at the intersection with Kensington Church Street. Kensington, London, England.

Photo by Ghouston via Wikimedia Commons.

The Coronavirus and its aftermath of lingering paranoia are the perfect excuse. Decentralisation and homeworking must be done. They must be done for the duration. They must be continued after that to maintain social distancing. No one will think ill of Barclays and WPP for taking the leap. No one will blame them for taking the leap in a way that involves a few deviations from course and a less than elegant landing. A year from now, these organisations will be making measurably larger profits than they would be otherwise. The mistakes will have been ignored.

And other organisations will follow. Whether the present crash will bring on a depression shaped like a V or an L, there is no doubt that, even if slowly at first, the wheels of commerce will continue turning. But they will be turning on different rails. As with any change of course, there will be winners and losers. I have already discussed how I can expect to be among the winners. I will leave that as said for the other winners — these being anyone who can find a market for doing from home what was previously required by custom and lack of imagination to be done somewhere else. I will instead mention the losers.

Most obvious among these will be anyone involved in commercial property. Landlords will find themselves with many more square feet to fill than prospective tenants want to fill. Rental and freehold values will crumble. Bearing in mind how much debt is carried by commercial landlords, there will be some interesting business failures in the next few years. Then there are the ancillary sectors — property management companies, commercial estate agents, maintenance companies. These employ swarms of architects and surveyors and lawyers and negotiators, of builders, plumbers, electricians, of drivers and cleaners. If the humbler workers will eventually find other markets, many with degrees and professional qualifications can look to a future of straitened circumstances.

The lush residential estates in and about Central London will follow. I think particularly of the aristocratic residential holdings in Kensington. Houses here go for tens of thousands a week to senior bank workers from abroad. If the City and Canary Wharf are emptied out, who needs to live in a place like Kensington? It has poor Underground connections. It is close by places like Grenfell Tower. Its residents keep predators at bay only by heavy investment of their own in security and by suspecting every knock on the door and every sound in the night. Many of the shops and eateries that make its High Street an enjoyable place to be will not reopen. Those that do reopen will be hobbled by continuing formal and informal rules on social distancing.

As a result, restaurants and pubs and coffee bars will begin to disappear. All but a few of these were barely making normal profit before they were closed last month. So few are in liquidation as yet only because so few petitions have been lodged in the courts. Most of them will now be surplus to requirement. The same can be said of hotels. Speaking for myself, I used to visit Cambridge twice a year on examinations business. I was always put up there for a couple of nights. I shall now do from home all that I did in Cambridge. I doubt I am alone. Zoom will destroy business travel. In the same way, bigger televisions plus continued social distancing will finish off the theatres and cinemas — also in decline before last month.

February 28, 2020

QotD: Greek and Roman views of markets

The debate over the Polanyi and Finley view of ancient economic organisation — or perhaps over the Marx and Weber and Polanyi and Finley views — does not seem to have been followed with much attention by libertarians and conservatives. It is worth following, even so. Beyond a very basic level, history is as much about the present as the past. Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is a masterpiece of pure history. But it is also an account of what he saw as the long night of reason — and its attendant nightmares — between the golden age of the Antonines and his own age, and an anxious search for reassurance that there would be no second sleep. Macaulay’s History of England is in part an attempt to legitimise the Victorian settlement as the culmination of historical processes that had their local origin in the 1680s. How readers can be brought to think about the past will insensibly affect how they see the present.

Now, if it could be shown that the Aztecs had no concept of market behaviour, and that they were motivated by considerations wholly different from our own, it would be of little consequence. Everything we know about Aztec civilisation raises doubts whether it was worth calling a civilisation. The Aztecs had no writing and were ignorant of metal working and wheeled transport. Their cultural values were expressed in ritual torture, mass human sacrifice and cannibalism. The Mayans and Toltecs and all the others of their sort seem to have been no better. We may deplore the brutality of the Spanish conquest, but still conclude that it was, on balance, a blessing for the peoples of South America.

But it is different with the empires of the ancient Near East — and very different with the Greeks and Romans. These latter races are our intellectual fathers. Everything we ourselves have achieved is built on the foundations they laid. They gave us the names of all our arts and sciences. Eighty per cent of the English vocabulary is derived from Greek or Latin. Knowledge of these languages may be less widely diffused than it was until a century ago. But the general prestige of the Greeks and Romans is barely less now than it was among the mediaeval pilgrims who gaped at the crumbling remains of the Colisseum and the Baths of Diocletian. If it can be shown that they were wholly unlike us in their economic motivations, that would surely place in doubt the notion that market behaviour is natural to us.

And if few people outside the relevant university departments have read Polanyi and Finley, their conclusions are transmitted through popular histories and newspaper articles and television documentaries, and through large numbers of students who, however superficially, are exposed to these conclusions.

Sean Gabb, “Market Behaviour in the Ancient World: An Overview of the Debate”, 2008-05.