At Oxford Sour, Christopher Gage considers the prominent media narrative about the inevitability of a “majority-minority” America within the next twenty years:

According to both the Daily Stormer and the Washington Post‘s Jennifer Rubin, white people will be a minority sometime in the 2040s.

In 2008, the U.S. Census Bureau projected that “non-Hispanic” white Americans would fall to 49 percent by the year 2042.

Since then, breathless media-politicos have taken the coming “majority-minority” as gospel. Some on the left celebrate the forthcoming date as the first day of their permanent dominance. Some on the right employ the doomsday date to encourage lunatics to rub out innocent people in a synagogue.

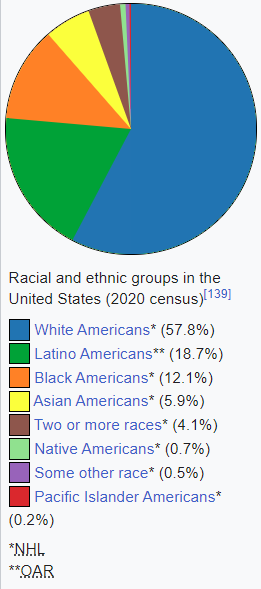

The 2020 census continued the theme. Breathless, lazy journalists took the clickbait. Ominously, they said the white population was “shrinking”. According to the Census Bureau, the white population shrunk to just 57.8 percent. Michael Moore did a little dance.

On white nationalist forums, users with names like WhiteGenocide88 were traumatised, and tooling up for war. No doubt, there are a few Robert Bowers with monstrous campaigns lurking around their skulls.

The problem with this theory, or so my Jewish puppet masters instruct me to say, is that it’s nonsense.

Firstly, the white population didn’t “shrink”. Not unless one believes the Jim Crow “one-drop” rule meaning one non-white ancestor renders one non-white. Secondly, the census ignores millions of white Americans who check the “Hispanic” box. These Americans more than cover any white decline.

According to the census, only those of one hundred percent white European ancestry are white. The Ku Klux Klan tends to agree.

For the first time on the census form, white people could include their varied multi-racial ancestry. Over 31 million whites did so. When we count these white people as white, the white population climbs to 71 percent. So, rather than “shrinking”, the white population has since 2010 increased by four million.

With a sensible definition of white, even by 2060, America remains around 70 percent white.

Professor Richard Alba, a sociologist at the City University of New York, says that definition means America remains a majority-white nation indefinitely — no doomsday clock, no murderous rampages, no primitive bloodsport over a faulty horoscope.

I’m no demographer but counting all white people as white people means there are more white people. I’m no sociologist either but revealing the increase in white people means fewer Robert Bowers keen to pump shotgun rounds into human flesh.

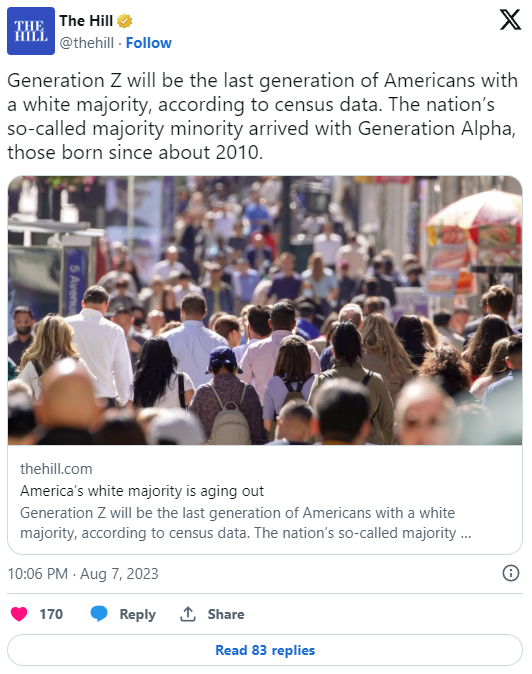

At Not the Bee, Joel Abbott is concerned about the obvious glee displayed by legacy media folks when they push the “replacement” story line:

You can practically feel the excitement here from the quivering fingers of the journalist that wrote this.

Ah.

Hmm.

Well, this is awkward.

See, I’m told this isn’t happening. White people aren’t being “replaced,” they’re just simply being phased out with a percentage that isn’t white at the same time all our institutions, companies, and leaders are pushing to eradicate things like “whiteness” and “white rage” in the name of equity.

For the record, I really couldn’t care less about the skin color of who lives in America. I care an infinite amount more about the spiritual worldview and values of my neighbor than whether their physical DNA gave them dark skin, blue eyes, or a big nose.

This is why I find it weird that the media keeps reporting, with abject glee, that people who look like me will be in the minority soon.