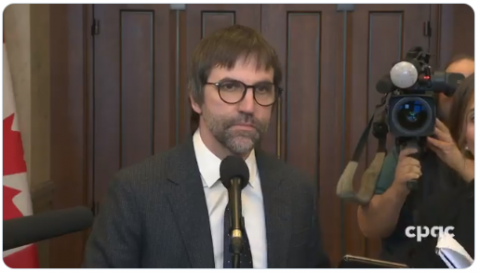

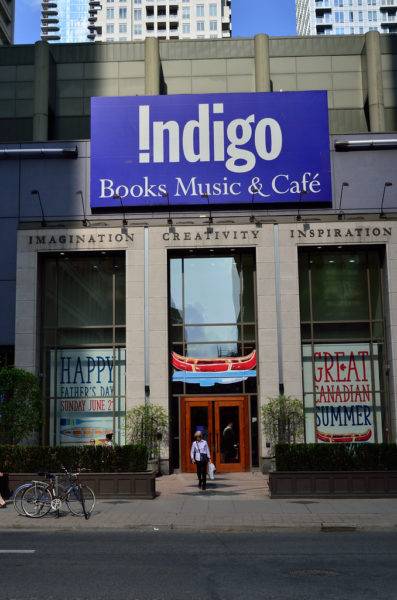

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte reviews a recent BNN Bloomberg interview with Heather Reisman former-and-now-current-again CEO of Canada’s only big box book retailer, Indigo:

“Indigo Books and Music” by Open Grid Scheduler / Grid Engine is licensed under CC0 1.0

Heather Reisman gave an interview to Amanda Lang of BNN Bloomberg last week, her first effort to explain a summer of screwball management at Canada’s only bricks-and-mortar book chain.

[…]

How did Heather explain the zany sequence of events that started with her reporting Indigo’s fourth massive annual loss in five years in May; saw her booted in June from her role as executive chairman of Indigo, the company she founded, by her husband and controlling shareholder, Gerry Schwartz, along with every member of the board of directors who wasn’t personally beholden to Gerry; saw her spin her exit as a personal life-stages choice (“deciding when it is time to move on is one of the toughest decisions a founder must make”); saw her hand-picked successor and CEO, long-time British clothing retailer Peter Ruis, grab a seven-figure payout and make his own exit in September; saw the company announce that it would “act swiftly to find the right leader to move the company forward following Peter’s resignation”; saw Heather reinstated at the head of the chain two weeks later?

She didn’t. How could anyone explain that?

Heather bullshitted her way through the interview. It was all Ruis’s fault, she told Amanda. Indigo “took a journey off brand” under Ruis. She’d put him in charge of a book chain and “suddenly I was hearing that we were getting famous for selling $550 barbecues,” she said. “Somehow vibrators turned up in our stores and I remember saying ‘no, that’s not who we are.'” Ruis had “lost sight of … what our commitment is to customers.” He was “taking the business in the wrong direction” and it was showing up in the financials.

Heather claimed she’d been powerless to stop Ruis: “I was gone formally for over a year and informally for two and a half years in the sense that I was pulling back and not able to influence things.”

I scarcely know where to start. We could talk about the breathtaking ease with which Heather presented herself as a victim of Ruis while running him over with a forklift. How she hired a career fashion retailer to run what most Canadians still understand as a book chain and complained that he took the business off brand. How his barbecues and dildo merchandising was a logical extension of the cheeseboards and blankets merchandising she’d been doing for a decade.

If we were a serious business publication, we’d have to talk about her supposed powerlessness to do anything about the dildo-happy Ruis. The people who run public companies have duties to their shareholders, one of which is to keep them informed—promptly, honestly, transparently—about the management of the business. If Heather was gone “formally for over a year” and “informally for two and a half years,” investors should have known, right?

Let’s start with “formally for over a year.” Heather is referring to the most recent period of September 2022 to August 2023 during which Barbecue Boy was CEO of the company. Was Heather gone?

She was no longer CEO, a title she’d held for a quarter century, but according to corporate records she remained executive chairman of Indigo during that time, drawing an annual salary of almost a million. Titles matter in public companies. The difference between an executive chairman and a run-of-the-mill chairman is that the former is recognized as having an active role in the operations of the business, hence the executive-level salary. Executive chairman is higher on the org chart than CEO. If the company was moving off brand, betraying its customers, she was the one person with the formal role and the moral authority, as founder, to send the “four hours of fun” Firefighter Vibrator from Smile Makers ($75.00) back to the warehouse. Either Heather misspoke to Amanda last week about being “gone” or she spent her last year at Indigo misrepresenting herself to her shareholders and drawing a salary under false pretenses.