David Friedman comments on Orwell’s essay “Rudyard Kipling“, published a few years after the poet’s death in Horizon, September 1941:

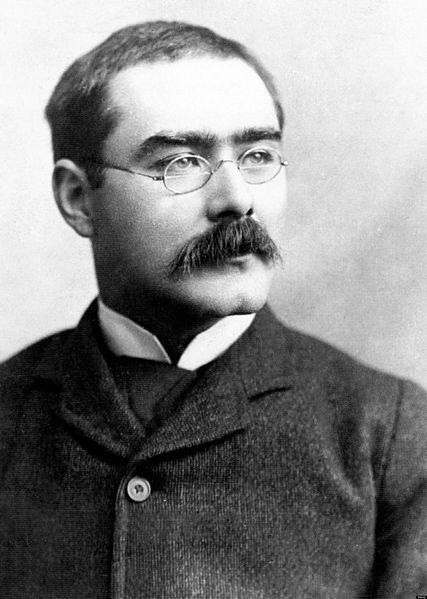

Portrait of Rudyard Kipling from the biography Rudyard Kipling by John Palmer, 1895.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

During five literary generations every enlightened person has despised him, and at the end of that time nine-tenths of those enlightened persons are forgotten and Kipling is in some sense still there.

Orwell’s essay on Rudyard Kipling in the Letters and Essays is both more favorable and more perceptive than one would expect of a discussion of Kipling by a British left-wing intellectual c. 1940. Orwell recognizes Kipling’s intelligence and his talent as a writer, pointing out how often people, including people who loath Kipling, use his phrases, sometimes without knowing their source. And Orwell argues, I think correctly, that Kipling not only was not a fascist but was further from a fascist than almost any of Orwell’s contemporaries, left or right, since he believed that there were things that mattered beyond power, that pride comes before a fall, that there is a fundamental mistake in

heathen heart that puts her trust

In reeking tube and iron shard,

All valiant dust that builds on dust,

And guarding, calls not Thee to guard,But while there is a good deal of truth in Orwell’s discussion of Kipling it is mistaken in two different ways, one having to do with Kipling’s view of the world, one with his art.

Orwell writes:

It is no use claiming, for instance, that when Kipling describes a British soldier beating a ‘nigger’ with a cleaning rod in order to get money out of him, he is acting merely as a reporter and does not necessarily approve what he describes. There is not the slightest sign anywhere in Kipling’s work that he disapproves of that kind of conduct — on the contrary, there is a definite strain of sadism in him, over and above the brutality which a writer of that type has to have.

There are passages in Kipling, not “Loot“, the poem Orwell quotes but bits of Stalky and Company, which support the charge of a “strain of sadism”. But the central element which Orwell is misreading is not sadism but realism. Soldiers loot when given the opportunity and there is no point to pretending they don’t. School boys beat each other up. Schoolmasters puff up their own importance by abusing their authority to ridicule the boys they are supposed to be teaching. Life is not fair. And Kipling’s attitude, I think made quite clear in Stalky and Company, is that complaining about it is not only a waste of time but a confession of weakness. You should shut up and deal with it instead.

A more important error in Orwell’s essay is his underestimate of Kipling as an artist, both poet and short story writer. Responding to Elliot’s claim that Kipling wrote verse rather than poetry, Orwell claims that Kipling was actually a good bad poet:

What (Elliot) does not say, and what I think one ought to start by saying in any discussion of Kipling, is that most of Kipling’s verse is so horribly vulgar that it gives one the same sensation as one gets from watching a third-rate music-hall performer recite ‘The Pigtail of Wu Fang Fu’ with the purple limelight on his face, AND yet there is much of it that is capable of giving pleasure to people who know what poetry means. At his worst, and also his most vital, in poems like ‘Gunga Din’ or ‘Danny Deever’, Kipling is almost a shameful pleasure, like the taste for cheap sweets that some people secretly carry into middle life. But even with his best passages one has the same sense of being seduced by something spurious, and yet unquestionably seduced.

I am left with the suspicion that Orwell is basing his opinion almost entirely on Kipling’s best known poems, such as the two he cites here, both written when he was 24. He was a popular writer, hence his best known pieces are those most accessible to a wide range of readers. He did indeed use his very considerable talents to tell stories and to make simple and compelling arguments, but that is not all he did. There is no way to objectively prove that Kipling wrote quite a lot of good poetry and neither Orwell nor Elliot, unfortunately, is still alive to prove it to, but I can at least offer a few examples …