Geography By Geoff

Published Jul 16, 2024Did you know that Newfoundland and Labrador were once an independent country in the same manner as Canada was? It’s true! It was called the Dominion of Newfoundland and due to a series of unfortunate events, it had to relinquish its independence. In today’s video, we cover the vast geography of the province, it’s very old history (including Vikings!) and how the country managed to lose its independence when it managed to survive on its own for decades. Oh … and we’ll also talk about why Labrador got included in the name upon confederating with Canada.

(more…)

November 24, 2024

How Newfoundland and Labrador lost their independence

November 23, 2024

How the US Paranoia of Leftism was Born

World War Two

Published 21 Nov 2024Elizabeth Bentley’s defection in 1945 didn’t just expose a Soviet spy network — it fueled America’s second Red Scare and a wave of anti-communist paranoia. Her revelations about Soviet infiltration within the U.S. government became a catalyst for McCarthyism, reshaping American politics and society in an era defined by fear and suspicion.

(more…)

QotD: Nietzsche’s message

[Nietzsche’s] objection to Christianity is simply that it is mushy preposterous, unhealthy, insincere, enervating. It lays its chief stress, not upon the qualities of vigorous and efficient men, but upon the qualities of the weak and parasitical. True enough, the vast majority of men belong to the latter class: they have very little enterprise and very little courage. For these Christianity is good enough. It soothes them and heartens them; it apologizes for their vegetable existence; it fills them with an agreeable sense of virtue. But it holds out nothing to the men of the ruling minority; it is always in direct conflict with their vigor and enterprise; it seeks incessantly to weaken and destroy them. In consequence, Nietzsche urged them to abandon it. For such men he proposed a new morality — in his own phrase, a “transvaluation of values” — with strength as its highest good and renunciation as its chiefest evil. They waste themselves to-day by pulling against the ethical stream. How much faster they would go if the current were with them! But as I have said — and it cannot be repeated too often — Nietzsche by no means proposed a general repeal of the Christian ordinances. He saw that they met the needs of the majority of men, that only a small minority could hope to survive without them. In the theories and faiths of this majority he has little interest. He was content to have them believe whatever was most agreeable to them. His attention was fixed upon the minority. He was a prophet of aristocracy. He planned to strike the shackles from the masters of the world …

H.L. Mencken, “Transvaluation of Morals”, The Smart Set, 1915-03.

November 22, 2024

Kalthoff 30-Shot Flintlock: The First Repeating Firearm Used in War (1659)

Forgotten Weapons

Published Aug 7, 2024The first repeating rifle used in combat by a military force was a flintlock system developed by the Kalthoff brothers. It was adopted in the 1640s by the Danish Royal Guard, who purchased a bit more than 100 of the guns, and used them successfully in the Siege of Copenhagen in 1659. The Kalthoff is a .54 caliber flintlock rifle with a magazine of 30 balls under the barrel and a powder storage compartment in the buttstock. A lever under the action is rotated forward 180 degrees and then back to completely reload the rifle — this action loads a ball into the chamber, seats it fully in place, loads powder behind it, primes the pan, cocks the hammer, and closes the frizzen. This was an amazing amount of firepower in the mid-1600s, and the mechanism in the gun is brilliant.

The Kalthoff brothers (Peter, Mathias, Caspar, Henrik, and William) spread out across Europe working for many royal courts although it was in Denmark where their gun saw the most substantial military use. The system would lead to other repeating flintlock designs like the Lorenzoni, but these did not really meet the quality of the original Kalthoffs (in my opinion). However, the system was very expensive to make and rather fragile to use. By 1696 the Danes had taken them out of service in favor of simpler and more durable designs. Kalthoffs today are very, very rare, and it was an incredible privilege to be able to take this one apart to show to you. Many thanks to Jan, its owner, for letting me do that!

(more…)

QotD: Pre-modern armies on the move

Armies generally had to move over longer distances via roads, for both logistical and pathfinding reasons. For logistics, while unencumbered humans can easily clamber over fences or small ridges or weave through forests, humans carrying heavy loads struggle to do this and pack animals absolutely cannot. Dense forests (especially old growth forests) are formidable obstacles for pack and draft animals, with a real risk of animals injuring themselves with unlucky footfalls. After all the donkey was originally a desert/savannah creature and horses evolved on the Eurasian Steppe; dense forest is a difficult, foreign terrain. But the rural terrain that would dominate most flat, arable land was little better: fields are often split by fences or hedgerows which need to be laboriously cleared (essentially making a path) to allow the work animals through. Adding wagons limits this further; pack mules can make use of narrow paths through forests or hills, but wagons pulled by draft animals require proper roads wide enough to accommodate them, flat enough that the heavy wagon doesn’t slide back and with a surface that will be at least somewhat kind on the wheels. That in turn in many cases restricts armies to significant roadways, ruling out things like farmer’s paths between fields or small informal roads between villages, though smaller screening, scouting or foraging forces could take these side roads.

(As an aside: one my enduring frustrations is the tendency of pre-modern strategy games to represent most flat areas as “plains” of grassland often with a separate “farmland” terrain type used only in areas of very dense settlement. But around most of the Mediterranean, most of the flat, cleared land at lower elevations would have been farmland, with all of the obstructions and complications that implies; rolling grasslands tend to be just that – uplands too hilly for farming.)

The other problem is pathfinding and geolocation. Figuring out where you off-road overland with just a (highly detailed) map and a compass is sufficiently difficult that it is a sport (Orienteering). Prior to 1300, armies in the broader Mediterranean world were likely to lack both; the compass (invented in China) arrives in the Mediterranean in the 1300s and detailed topographical maps of the sort that hikers today might rely on remained rare deep into the modern period, especially maps of large areas. Consequently it could be tricky to determine an army’s exact heading (sun position could give something approximate, of course) or position. Getting lost in unfamiliar territory was thus a very real hazard. Indeed, getting lost in familiar territory was a real hazard: Suetonius records that Julius Caesar, having encamped not far from the Rubicon got lost trying to find it, spent a whole night wandering trying to locate it (his goal being to make the politically decisive crossing with just a few close supporters in secrecy first before his army crossed). In the end he had to find a local guide to work his way back to it in the morning (Suet. Caes. 31.2). So to be clear: famed military genius Julius Caesar got lost trying to find a 50 mile long river only about 150 miles away from Rome when he tried to cut cross-country instead of over the roads.

Instead, armies relied on locals guides (be they friendly, bought or coerced) to help them find their way or figure out where they were on whatever maps they could get together. Locals in turn tend to navigate by landmarks and so are likely to guide the army along the paths and roads they themselves use to travel around the region. Which is all as well because the army needs to use the roads anyway and no one wants to get lost. The road and path network thus becomes a vital navigational aid: roads and paths both lead to settlements full of potential guides (to the next settlement) and because roads tend to connect large settlements and large settlements tend to be the objectives of military campaigns, the road system “points the way”. Consequently, armies rarely strayed off of the road network and were in most cases effectively confined to it. Small parties might be sent out off of the road network from the main body, but the main body was “stuck” on the roads.

That means the general does not have to cope with an infinitely wide range of maneuver possibilities but a spiderweb of possible pathways. Small, “flying columns” without heavy baggage could use minor roads and pathways, but the main body of the army was likely to be confined to well-traveled routes connecting large settlements.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Logistics, How Did They Do It, Part III: On the move”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-08-12.

November 21, 2024

1966: Chieftain Tank Simulator | Tomorrow’s World | Retro Tech | BBC Archive

BBC Archive

Published Jul 15, 2024“All the tension, the excitement, and indeed the technical demands of driving a modern tank into battle … but, in fact, I haven’t moved a yard.”

Raymond Baxter test drives the British Army’s Chieftain tank simulator, used for training tank drivers. The illusion is created using a large 1:300 scale model of the battlefield, a computer, and a roving mirror connected to a television camera. The battlefield can be altered simply by swapping out the model trees and buildings.

Mr Baxter can attest to how realistic the experience is, and it costs just one tenth of the price of training in a real Chieftain tank.

Clip taken from Tomorrow’s World, originally broadcast on BBC One, 28 September, 1966.

November 20, 2024

The Korean War Week 22 – Winter is Coming! – November 19, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 19 Nov 2024Eighth Army commander Walton Walker makes his final preparations for the big push north to the Yalu River. The Communist Chinese prepare their own forces and wait for the Americans to make their move. At the same time, the freezing Korean winter arrives in force, plunging temperatures well below freezing. The Americans must get this done, and soon.

(more…)

November 19, 2024

The state and society

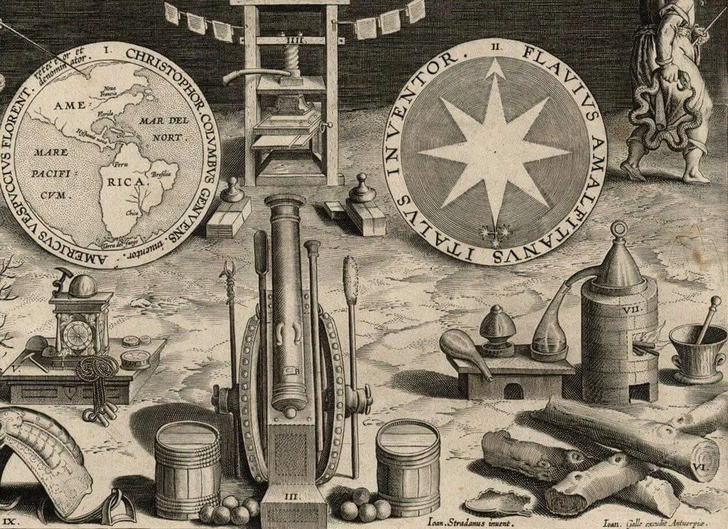

Lorenzo Warby explains why Karl Marx was wrong about the origins of what he called “the three great inventions” and therefore also mistaken about the societal impact of those inventions:

Gunpowder, the compass, and the printing press were the 3 great inventions which ushered in bourgeois society. Gunpowder blew up the knightly class, the compass discovered the world market and founded the colonies, and the printing press was the instrument of Protestantism and the regeneration of science in general; the most powerful lever for creating the intellectual prerequisites.

Karl Marx, “Division of Labour and Mechanical Workshop. Tool and Machinery” in Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63, Part 3) Relative Surplus Value.

With this quote we can see what is wrong both with Marx’s notion of the role of technology in social causation and with a very common notion of the relationship between state and society.

The false — but very common — view of the relationship of state and society is that the state is a product of its society, that the state emanates from its society. This gets the dominant relationship almost entirely the wrong way around. It is far more true to say that the state is a fundamental structuring element of the social dynamics of the territory it rules rather than the reverse.

It is perhaps easiest to see this by noting the glaring flaw in Marx’s reasoning. The gunpowder, the compass and the printing press were all originally Chinese inventions. Indeed, Europe acquired — via intermediaries — gunpowder and the compass from China. (Gutenberg’s printing press appears to have been an independent invention.)

Source: Nova Reperta Frontispiece, 1588.

Yet, as Marx was very well aware, China did not develop a bourgeoisie in his sense. Indeed, Marx’s notion of the Asiatic mode of production grappled with precisely that lack.1

In 1620, Sir Francis Bacon wrote in his Instauratio magna that

… printing, gunpowder, and the nautical compass … have altered the face and state of the world: first, in literary matters; second, in warfare; third, in navigation …

This was true of the effect of these inventions in European, but not Chinese, hands.

Why were these inventions globally transformative in European, but not Chinese hands? Because of the differences in the structure of European state(s) compared to the Chinese state.

Unified China …

The first difference is that the European states were states, plural. Europe had competitive jurisdictions, it had centuries of often intense inter-state conflict. From the Sui (re)unification (581) onwards China was, with brief interruptions, a single polity.2 What the evidence — both Chinese and Roman — shows quite clearly is that civilisational unity in a single polity is bad for institutional, technological and intellectual development.

The second difference is with the internal structure of European states compared to the Chinese state. The Sui dynasty, by introducing the Keju, the imperial examination — refining the use of appointment by exam that went back to the Warring States period — created a structure that directed Chinese human capital to the service of the Emperor.

There were three tiers of examinations (local, provincial, palace). You could sit for them as often as you wished. So a significant proportion of Chinese males devoted decades of their lives to attempting to pass the exams. Over time, the exams became more narrowly Confucian — probably because it required a high level of detailed mastery, so had more of a sorting effect — thereby promoting intellectual conformism.

[…]

… and divided Europe

Conversely, when gunpowder, the compass and the printing press came to Europe, European states already had a military aristocracy; self-governing cities; an armed mercantile elite; organised religious structures; so a rich array of cooperative institutions. Moreover, kin-groups had been suppressed across manorial Europe, forcing — or giving the social space for — alternative mechanisms for social cooperation to evolve.3, 4 In particular, due [to] its self-governing cities with armed militias, medieval Europe had an (effectively) armed mercantile elite before gunpowder, the compass or printing reached Europe.

Alfonso IX of Leon and Galicia (r.1188-1230) first summoned the Cortes of Leon in 1188. This became the start of the first institutionalised use of merchant representatives in deliberative assemblies. Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (r.1155-1190) had tried something similar earlier, but the mercantile elites of North Italy preferred de facto independence, defeating him at the Battle of Legnano in 1176.

The first European reference to the compass is in a text written some time between 1187 and 1202, with its use appearing to expand over the 1200s. The first reference to gunpowder in Europe is not until 1267 and it took centuries before gunpowder played a major role in European warfare.

Both the compass and gunpowder really only have transformative effects from the late C15th onwards, which is also when the printing press is spreading across Latin Europe. By that time, medieval Europe has already become a machine culture and it had been for centuries the civilisation with the most powerful mercantile elite. A reality driven by competitive jurisdictions, a rural-based military aristocracy, law that was not based on revelation (so it could entrench social bargains), suppression of kin-groups, and self-governing cities.

Competition between European states was a powerful driver of the transformative use of technologies. But so was the level of striving within such states: adventurers able to mobilise resources — and seeking wealth, power, prestige — had far more room to operate (and receive official sanction) in Europe than in China.

In other words, the differences in the development and use of technology — and in social dynamics and formations — between China and medieval Europe was fundamentally driven by the differences in state structures, in how the relevant polities worked.

1. Marx was not an honest intellectual reasoner:

As to the Delhi affair, it seems to me that the English ought to begin their retreat as soon as the rainy season has set in in real earnest. Being obliged for the present to hold the fort for you as the Tribune’s military correspondent I have taken it upon myself to put this forward. NB, on the supposition that the reports to date have been true. It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way.

Marx to Engels, [London,] 15 August 1857, (emphasis in the original).2. The Song (960-1279) failed to fully unify China, but they were the only significant Han polity. That the Song were effectively within a mini-state system does seem to have affected their policies, including the unusually — for a Chinese imperial dynasty — strong focus on trade and technological development.

3. Kin-groups had already been suppressed in the city-states of the Classical world, including Rome. They re-emerged with the incoming Germanic peoples, and then were suppressed again by the Church and the manorial elite, remaining in the agro-pastoralist Celtic fringe and Balkan uplands.

4. Economists Avner Greif and Guido Tabellini define clan (i.e. kin-group) as “a kin-based organization consisting of patrilineal households that trace their origin to a (self-proclaimed) common male ancestor“. They contrast this with a corporation: “a voluntary association between unrelated individuals established to pursue common interests“. They note they perform similar functions: “they sustained cooperation among members, regulated interactions with non-members, provided local public or club goods, and coordinated interactions with the market and with the state“. Triads, tongs and cults can also perform these functions.

WF-51: A Swiss Intermediate-Cartridge Copy of the FG-42

Forgotten Weapons

Published Aug 5, 2024After World War Two the Swiss needed a new self-loading military rifle to replace their K-31 bolt actions. Two major design tracks followed; one being a roller-delayed system based on the G3 at SIG and the other being a derivative of the German FG-42 at Waffenfabrik Bern. Bern, under the direction of Adolph Furrer, had been experimenting with intermediate cartridges since the 1920s, and they used this as a basis to develop an improved FG-42 using an intermediate cartridge (7.5x38mm). The program began in 1951 and went through about a half dozen major iterations until it ultimately lost to the SIG program (which produced the Stgw-57).

Today we are looking at one of the first steps in the Bern program, the WF-51. The most substantial change form the FG42 design here is the use of a tilting bolt instead of a rotating bolt like the Germans used. It is a beautifully manufactured firearm, and a real pleasure to take a look at …

Many thanks to the Royal Armouries for allowing me to film and disassemble this rifle! The NFC collection there — perhaps the best military small arms collection in Western Europe — is available by appointment to researchers:

https://royalarmouries.org/research/n…You can browse the various Armouries collections online here:

https://royalarmouries.org/collection/

(more…)

QotD: The Reformation

The Reformation’s great complaint against the late-medieval Church is that it, the Church, had turned Catholicism entirely into a process. Those naive folks who argue that life wasn’t so hard for the medieval peasant because he had all those days off — 180 some odd saints’ days, feast days, and so on — have a bit of a point for all that. Ritual life simply was community life; “free time” as we understand it just wasn’t a thing in the middle ages, and not just because life was such a constant struggle. Every hour of your day carried its obligation to someone; there’s a reason the very best sources for “daily life in the middle ages” are called books of hours.

Your hotter Protestants, your John Calvins and Oliver Cromwells and so on, saw all of this as mere ritual. And to be fair to them, late-medieval Catholicism was very elaborate, and very, very weird — slog through a few chapters of The Stripping of the Altars if you want the details. To the Prods, this was cheating — you can’t just go through the motions and expect to get into Heaven. They made a similar distinction between “natural magic” and the unlawful stuff — the one was undertaken only after deep study and the most rigorous self-purification, while the other “worked” entirely mechanically, because what the sorcerer was really doing was cheating; he was really making a deal with a (or The) devil, to short-circuit the natural processes.

Now, it’s important to realize that the Protestants were not saying anything close to “do your own thing, man”. They were NOT hippies, encouraging everyone to read the Bible and decide for themselves how best to commune with the Big JC. The German peasants thought that’s what Martin Luther was saying back in 1524, but Luther himself was out there urging the authorities to smash the peasants with extreme prejudice. The Protestants were, in fact, extremely concerned about ritual. It just had to be the right ritual, the Biblically sanctioned ritual, and nothing but that — that’s what “Puritanism” (originally an insult) means.

Severian, “Faith vs. Works”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-09-07.

November 18, 2024

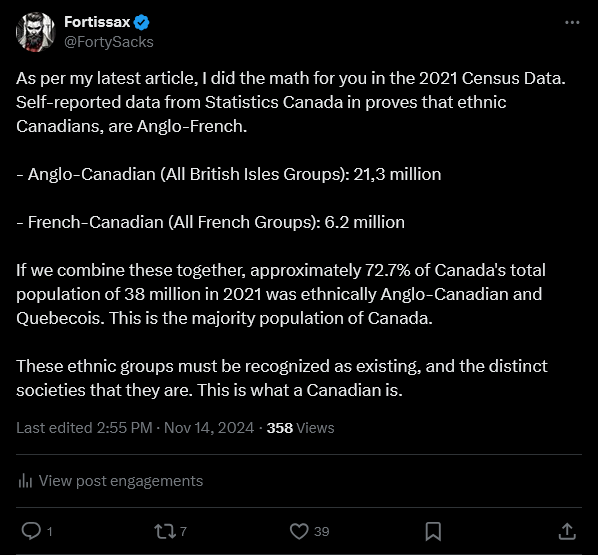

“The Great Canadian Lie is the claim that we’ve ‘always been multicultural'”

Fortissax thinks that the rest of Canada has lessons to be learned from Quebec:

If you are a Canadian born at any point in the Post-WWII era, you have been subjected to varying degrees of liberal “Cultural Mosaic” propaganda. This narrative exploits the historic presence of three British Isles ethnic groups (which had already been intermixing for millennia) and the predominantly Norman French settlers to justify the unprecedented mass migration of people from the Third World into Canada. This process only began in earnest in the 1990s before accelerating rapidly in the 2010s.

The Great Canadian Lie is the claim that we’ve “always been multicultural”, as though the extremely small and inconsequential presence of “Black Loyalists” or the historically hostile Indigenous groups (making up only 1% of the population at Canada’s founding in 1867) played any serious role in shaping the Canadian nation, its identity, institutions, or culture. Inspired by Dr. Ricardo Duchesne’s book Canada in Decay: Mass Immigration, Diversity, and the Ethnocide of Euro-Canadians (2017), which chronicled the emergence of two ethnic groups uniquely born of the New World, I delved into the 2021 Census data collected by the Canadian government to explore the ethnic breakdown of White Canadians in greater detail

The evidence is clear. In 2021, just four years ago, 72.7% of the entire Canadian population was not just White, but Anglo-Canadian and French-Canadian, representing an overwhelming presence compared to visible minorities and other White ethnic groups, such as the small populations of Germans and Ukrainians.

In the space last night, I highlighted this historical fact and explained to the audience the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Canadian and its significance. While we all recognize that the Québécois are a homogeneous group descended predominantly from Norman French settlers — such as the Filles du Roi and Samuel de Champlain’s 1608 expedition, which established Quebec City with a single-minded purpose — the Anglo-Canadian story also deserves similar recognition for its role in shaping Canada’s identity.

But what is less known is that Anglo-Canadians are just as ethnically homogeneous as the Québécois, from Nova Scotia to British Columbia. Anglo-Canadian identity emerged from Loyalist Americans in the 1750s, beginning with the New England Planters in Nova Scotia — “continentals” with a culture distinct from both England and the emergent Americans. After the American Revolutionary War, they marched north with indomitable purpose, like Aeneas and the Trojans, to rebuild their Dominion. Author Carl Berger, in his influential work The Sense of Power: Studies in the Ideas of Canadian Imperialism, demonstrates that the descendants of Loyalists were the one ethnic group that nurtured “an indigenous British Canadian feeling.” The following passage from Berger’s work is worth citing:

The centennial arrival of the loyalists in Ontario coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of the incorporation of the City of Toronto and, during a week filled with various exhibitions, July 3 was set aside as “Loyalist Day”. On the morning of that day the platform erected at the Horticultural Pavilion was crowded with civic and ecclesiastical dignitaries and on one wall hung the old flag presented in 1813 to the York Militia by the ladies of the county. Between stirring orations on the significance of the loyalist legacy, injunctions to remain faithful to their principles, and tirades against the ancient foe, patriotic anthems were sung and nationalist poetry recited. “Rule Britannia” and “If England to Herself Be True” were rendered “in splendid style” and evoked “great enthusiasm”. “A Loyalist Song”, “Loyalist Days”, and “The Maple Leaf Forever”, were all beautifully sung

The 60,000 Loyalist Americans, who arrived in two significant waves, were soon bolstered by mass settlement from the British Isles. However, British settlers assimilated into the Loyalist American culture rather than imposing a British identity on the new Canadians. The first major wave of British settlers after the Loyalists primarily consisted of the Irish. Before Confederation in 1867, approximately 850,000 Irish immigrants settled in Canada. Between 1790 and 1815, an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 settlers, mainly from the Scottish Highlands and Ireland, also made their way to Canada.

Another large-scale migration occurred between 1815 and 1867, bringing approximately 1 million settlers from Britain to Canada, specifically to Ontario, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. New Brunswick was carved out from the larger province of Nova Scotia to make room for the influx of Loyalists. During this time, settlers from England, Scotland, and Ireland intermingled and assimilated into the growing Anglo-Canadian culture. Scottish immigrants, who constituted 10–15% of this wave, primarily spoke Gaelic upon arrival but adopted English as they integrated.

All settlers from the British Isles spoke English (small numbers spoke Gaelic in case of Scots), were ethnically and culturally similar, and had much more in common with each other than with their continental European counterparts.

Settlement would slow down in the years immediately preceding Confederation in 1867 but surged again during the period between 1896 and 1914, with an estimated 1.25 million settlers yet again from Britain moving to Canada as part of internal migration within the British Empire. These settlers predominantly also [went] to Ontario and the Maritimes, further forging the Anglo-Canadian identity.

A common misconception among Canadians is that Canada “was a colony” of Britain, subordinate to, or a “vassal state”. This is wrong. Canadians were the British, in North America. There were no restrictions on what Canadians could or could not do in their own Dominion. From the first wave of Loyalists onward, Canadians were regularly involved in politics and governance, actively participating in shaping the nation.

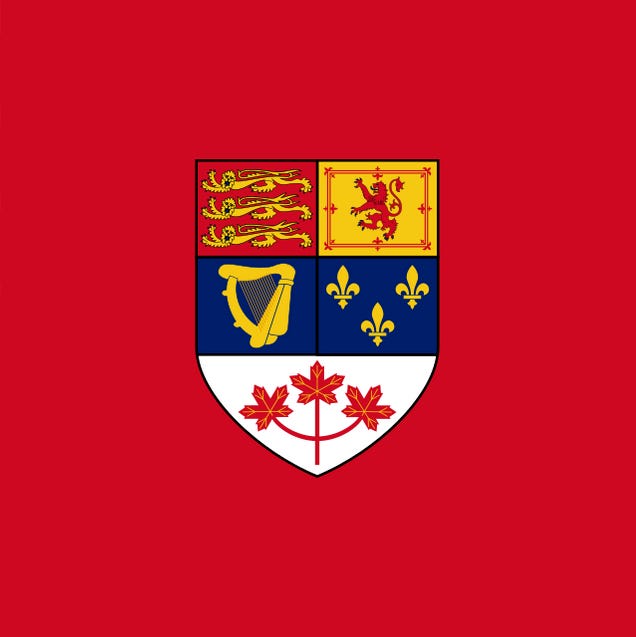

Like the ethnogenesis of the English, which saw Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians converge into a new people and ethnicity (the Anglo-Saxons), Anglo-Canadians are a combination of 1.9 million English, 850,000 Irish (from both Northern and Southern Ireland), and 200,000 Scots, converging with 60,000 Loyalist Americans from the 13 Colonies. These distinct yet similar ethnic groups no longer exist as separate peoples in Canada. Anglo-Canadians are the fusion of the entire British Isles. The Arms of Canada, the favourite symbol of Canadian nationalists today, represents this new ethnic group with the inclusion of the French:

It’s no coincidence that, once rediscovered, the Arms of Canada exploded in popularity as the emblem of Canadian nationalists. Unlike more controversial symbols that appeal to pan-White racial unity, such as the Sonnenrad or Celtic cross, the Arms of Canada resonate as a distinctly Canadian icon, deeply rooted in the nation’s true heritage and history — a heritage that cannot be bought, sold, or traded away. This is an immutable bloodline stretching into the ancient past. If culture is downstream from race, and deeper still, ethnicity, then Canadian culture, values, and identity are fundamentally tied not just its race, but its ethnic composition. The ethnos defines the ethos. Canadians are not as receptive to the abstract idea of White nationalism for the same reason Europeans aren’t — because they possess a cohesive ethnic identity, unlike most White Americans.

Changing the way “our leaders” speak to us

Ted Gioia says that the old rules of communicating to the public are undergoing a major shift.

Before they executed Socrates in the year 399 BC — on charges of impiety and corrupting youth — the philosopher was given a chance to defend himself before a jury.

Socrates started his defense with an unusual plea.

He told his listeners that he had no skill at making speeches. He just knew the everyday language of the common people.

Socrates explained that he had never studied rhetoric or oratory. He feared that he would embarrass himself by speaking so plainly in his trial defense.

“I show myself to be not in the least a clever speaker,” Socrates told the jurors, “unless indeed they call him a clever speaker who speaks the truth.”

He knew that others in his situation would give “speeches finely tricked out with words and phrases”. But Socrates only knew how to use “the same words with which I have been accustomed to speak” in the marketplace of Athens.

Socrates wasn’t exaggerating. His entire reputation was built on conversation. He never wrote a book — or anything else, as far as we can tell.

Spontaneous talking was the basis of his famous “Socratic method” — a simple back-and-forth dialogue. You might say it was the podcasting of its day. He aimed to speak plainly — seeking the truth through open and unfiltered conversation.

That might get you elected President in the year 2024. But it didn’t work very well in Athens, circa 400 BC.

Socrates received the death penalty — and was executed by poisoning.

Is that shocking? Not really.

Western culture was built on one-way communication. Leaders and experts speak — and the rest of us listen.

Socrates was the last major thinker to rely solely on conversation. After his death, his successors wrote books and gave lectures.

That’s what powerful people do. They make decisions. They give orders. They deliver speeches.

But not anymore.

In the aftermath of the election, the new wisdom is that giving speeches from a teleprompter doesn’t work in today’s culture. Citizens want their leaders to sit down and talk.

And not just in politics. You may have seen the same thing in your workplace — or in classrooms and other group settings. People now resist one-way orders from the top.

The word “scripted” is now an insult. Plainspoken dialogue is considered more trustworthy. This is part of the up-versus-down revolution I’ve written about elsewhere — a conflict that, I believe, may have even more impact on society than Left-versus-Right.

For better or worse, the hierarchies we’ve inherited from the past are toppling. To some extent, they are even reversing.

This is now impacting how leaders are expected to speak. Events of the last few days have raised awareness of this to a new level — but the “experts” should have expected it. That’s especially true because the experts will be those most impacted by this shift.

HBO’s Rome Ep. 3 “The owl in a thorn bush” – History and Story

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published Jul 17, 2024Episode Three: Now that Caesar has crossed the Rubicon, the Civil War has begun and the series gathers pace.

Vidcaps taken from the dvd collection and copyright belongs to the respective makers and channels.

Transcript

QotD: Napoleon and his army

To me the central paradox of Napoleon’s character is that on the one hand he was happy to fling astonishing numbers of lives away for ultimately extremely stupid reasons, but on the other hand he was clearly so dedicated to and so concerned with the welfare of every single individual that he commanded. In my experience both of leading and of being led, actually giving a damn about the people under you is by far the most powerful single way of winning their loyalty, in part because it’s so hard to fake. Roberts repeatedly shows us Napoleon giving practically every bit of his life-force to ensure good treatment for his soldiers, and they reward him with absolutely fanatical devotion, and then … he throws them into the teeth of grapeshot. It’s wild.

Napoleon’s easy rapport with his troops also gives us some glimpses of his freakish memory. On multiple occasions he chats with a soldier for an hour, or camps with them the eve before a battle; and then ten years later he bumps into the same guy and has total recall of their entire conversation and all of the guy’s biographical details. The troops obviously went nuts for this kind of stuff. It all sort of reminds me of a much older French tradition, where in the early Middle Ages a feudal lord would (1) symbolically help his peasants bring in the harvest and (2) literally wrestle with his peasants at village festivals. Back to your point about the culture, my anti-egalitarian view is that that kind of intimacy across a huge gulf of social status is easiest when the lines of demarcation between the classes are bright, clear, and relatively immovable. What’s crazy about Napoleon, then, is that despite him being the epitome of the arriviste he has none of the snobbishness of the nouveaux-riches, but all of the easy familiarity of the natural aristocrat.

True dedication to the welfare of those under your command,1 and back-slapping jocularity with the troops, are two of the attributes of a wildly popular leader. The third2 is actually leading from the front, and this was the one that blew my mind. Even after he became emperor, Napoleon put himself on the front line so many times he was practically asking for a lucky cannonball to end his career. You’d think after the fourth or fifth time a horse was shot out from under him, or the guy standing right next to him was obliterated by canister shot, the freaking emperor would be a little more careful, but no. And it wasn’t just him — the vast majority of Napoleon’s marshals and other top lieutenants followed his example and met violent deaths.

This is one of the most lacking qualities in leaders today — it’s so bad that we don’t even realize what we’re missing. Obviously modern generals rarely put themselves in the line of fire or accept the same environmental hardships as their troops. But it isn’t just the military, how many corporate executives do you hear about staying late and suffering alongside their teams when crunch time hits? It does still happen, but it’s rare, and the most damning thing is that it’s usually because of some eccentricity in that particular individual. There’s no systemic impetus to commanders or managers sharing the suffering of their men, it just isn’t part of our model of what leadership is anymore. And yet we thirst for it.

Jane and John Psmith, “JOINT REVIEW: Napoleon the Great, by Andrew Roberts”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-01-21.

1. When not flinging them into the face of Prussian siege guns.

2. Okay, there are more than three. Some others include: deploying a cult of personality, bestowing all kinds of honors and awards on your men when they perform, and delivering them victory after victory. Of course, Napoleon did all of those things too.