Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Jun 25, 2024Black mead, or bochet, made with spices and wood chips

City/Region: Paris

Time Period: 1393Mead was very popular from Russia to England, but started to lose favor in part due to the rise of cheaper brews like vodka and hopped ales. Mead was often still drunk for its medicinal properties, especially when it was infused with herbs and spices.

This mead has some of those wonderfully warming spices, and I added wood chips from the local brewing store to mimic the wood barrels that it would have been fermented in. The burnt caramel scent softens and mellows out during fermentation, and the resulting mead is not sweet at all and is more complex than many meads I’ve had.

To make six sextier of bochet, take six pints of very sweet honey, and put it in a cauldron on the fire and boil it, and stir for so long that it starts to grow, and you see that it also boils with bubbles like small blisters which will burst, releasing a little bit of dark smoke. Then add seven sextier of water and boil so much that it reduces to six sextiers, and keep stirring. And then put it in a vat to cool until it is lukewarm; then strain it through a cloth, and put it in a barrel and add a pint of yeast from ale, because that is what makes it piquant, (though if you use bread yeast, it makes as good a flavor, but the color will be duller), and cover well and warmly so it ferments.

If you want to make it very good, add an ounce of ginger, long pepper, grains of paradise and cloves in equal amounts, except for the cloves of which there should be the least, and put them in a cloth bag and toss it in. And when it has been two or three days and the bochet smells of spices and is strong enough, take out the bag and wring it out and put it in the next barrel that you make. And so this powder will serve you well up to three or four times.

— Le Ménagier de Paris, 1393.

October 8, 2024

Making the Black Mead of Medieval France – Bochet

October 3, 2024

D-Day 80th Anniversary Special, Part 2: Landings with firearms expert Jonathan Ferguson

Royal Armouries

Published Jun 12, 2024This year marks the 80th anniversary of D-Day, the Allied invasion of France which took place on 6th June 1944. From landing on the beaches of Normandy, the Allies would push the Nazi war machine and breach Hitler’s Atlantic Wall.

To commemorate this, we’re collaborating with IWM to release a special two-part episode as Jonathan will look at some of the weapons that influenced and shaped this historic moment in history.

Part 2 is all about the pivotal landings, including allied efforts to aid in its success.

0:00 Intro

0:25 Twin Vickers K Gun

2:03 Pointe du Hoc

2:45 Water off a DUKW’s back?

3:50 Magazines x3

4:07 Usage & History

5:50 Bring up the PIAT!

7:00 Dispelling (Or Projecting via Spigot) Myths

7:55 PIAT Firing Process

9:50 PIAT Details

10:31 Usage in D-Day

13:19 Pegasus Bridge

15:05 MG 42

15:41 Defensive Machine Gun

16:37 1200 RPM

17:35 Replaceable Barrel

19:08 Usage in D-Day

21:37 Sexton Self-Propelled Gun

21:33 Artillery in D-Day

22:15 Run-In Shoot

22:40 The Need for Mobile Artillery

23:25 Usage in D-Day

24:21 17-Pounder Gun

25:11 Function & Usage

26:05 Usage in D-Day

28:00 IWM at HMS Belfast

30:27 Outro

(more…)

October 1, 2024

QotD: Napoleon Bonaparte and Tsar Alexander I

Jane: … The most affecting episode in the whole book [Napoleon the Great by Andrew Roberts], to my mind — even more than his slow rotting away on St. Helena — is Napoleon’s conferences with Alexander I at Tilsit. Here are these two emperors meeting on their glorious raft in the middle of the river, with poor Frederick William of Prussia banished from the cool kids’ table, and Napoleon thinks he’s found a peer, a kindred soul, they’re going to stay up all night talking about greatness and leadership and literature … And the whole time the Tsar is silently fuming at the audacity of this upstart and biding his time until he can crush him. The whole buildup to the invasion has a horror movie quality to it — no, don’t go investigate that noise, just get out of

the houseRussia! — but even without knowing how horribly that turns out, you feel sorry for the guy. Napoleon thinks they have something important in common, and Alexander thinks Napoleon’s very existence is the enemy of the entire old world of authority and tradition and monarchy that he represents.Good thing the Russian Empire never gets decadent and unknowingly harbors the seeds of its own destruction!

John: Yeah, I think you’ve got the correct two finalists, but there’s one episode in particular on St. Helena that edges out his time bro-ing out with Tsar Alexander on the raft. It’s the supremely unlikely scene where old, beaten, obese, dying Napoleon strikes up a bizarre friendship with a young English girl. It all begins when she trolls him successfully over his army freezing to death in the smoldering ruins of Moscow, and after a moment of anger he takes an instant liking to her and starts pouring out his heart to her, teaching her all he knows about military strategy, and playing games in her parents’ yard where the two of them pretend to conquer Europe. Call me weird, but I think this above all really showcases Napoleon’s greatness of soul. That little girl later published her memoirs, btw, and I really want to read them someday.

Jane and John Psmith, “JOINT REVIEW: Napoleon the Great, by Andrew Roberts”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-01-21.

September 24, 2024

British stagnation – “at some point it becomes impossible to grow when investment is banned”

Ed West reviews a new essay by Ben Southwood, Samuel Hughes, and Sam Bowman which tries to identify the underlying reasons for British economic stagnation:

The theme running through the essay is that the British system makes it very hard to invest and extremely expensive and legally difficult to build, making housing and energy costs prohibitive.

While we all know we have fallen in status, “most popular explanations for this are misguided. The Labour manifesto blamed slow British growth on a lack of “strategy” from the Government, by which it means not enough targeted investment winner picking, and too much inequality. Some economists say that the UK’s economic model of private capital ownership is flawed, and that limits on state capital expenditure are the fundamental problem. They also point to more state spending as the solution, but ignore that this investment would face the same barriers and high costs that existing infrastructure projects face, and that deters private investment.”

The problem is that “all of these explanations take the biggest obstacles to growth for granted: at some point it becomes impossible to grow when investment is banned”.

Even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the industrial price of energy had tripled in under 20 years. Per capita electricity generation in Britain is only two-thirds that of France, and a third of the US, making us closer to developing countries like Brazil and South Africa than other G7 states. Transport projects are absurdly expensive, mired by planning rules, and all of this helps explain why annual real wages for the median full-time worker are 6.9 per cent lower than in 2008.

In one of the most notorious examples, the authors note that “the planning documentation for the Lower Thames Crossing, a proposed tunnel under the Thames connecting Kent and Essex, runs to 360,000 pages, and the application process alone has cost £297 million. That is more than twice as much as it cost in Norway to actually build the longest road tunnel in the world.”

Britain’s political elites have failed, they argue, because they do not understand the problems, so “they tinker ineffectually, mesmerised by the uncomprehended disaster rising up before them”.

Even “before the pandemic, Americans were 34 percent richer than us in terms of GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power, and 17 percent more productive per hour … The gap has only widened since then: productivity growth between 2019 and 2023 was 7.6 percent in the United States, and 1.5 percent in Britain … the French and Germans are 15 percent and 18 percent more productive than us respectively.” The gap continues to widen, and on current trends, Poland will be richer than the United Kingdom by the end of the decade.

Britain began to fall behind after the War, but after decades of relative stagnation, its GDP per capita had converged with the US, Germany and France in the 1980s, and our relative wealth peaked in the early Blair years. (Personally, I wonder if one reason for the great Oasis nostalgia is simply that we were rich back then.) If Britain had continued growing in line with its 1979-2008 trends, average income today would be £41,800 instead of £33,500 — a huge difference.

France is the most natural comparison point to Britain, a country “notoriously heavily regulated and dominated by labour unions”. This is sometimes comical to British sensibilities, so that “French workers have been known to strike by kidnapping their chief executives – a practice that the public there reportedly supports – and strikes are so common that French unions have designed special barbecues that fit in tram tracks so they can grill sausages while they march.” Only in France.

It is also heavily taxed, especially in the realm of employment, and yet despite this, French workers are significantly more productive. The reason is that France “does a good job building the things that Britain blocks: housing, infrastructure and energy supply”.

With a slightly smaller population, France has 37 million homes compared to our 30 million. “Those homes are newer, and are more concentrated in the places people want to live: its prosperous cities and holiday regions. The overall geographic extent of Paris’s metropolitan area roughly tripled between 1945 and today, whereas London’s has grown only a few percent.” One quality-of-life indicator is that “800,000 British families have second homes compared to 3.4 million French families“.

They also do transport far better, with 29 tram networks compared to seven in Britain, and six underground metro systems against our three. “Since 1980, France has opened 1,740 miles of high speed rail, compared to just 67 miles in Britain. France has nearly 12,000 kilometres of motorways versus around 4,000 kilometres here … In the last 25 years alone, the French built more miles of motorway than the entire UK motorway network. They are even allowed to drive around 10 miles per hour faster on them.”

September 22, 2024

QotD: The work of Le Corbusier

The sheer megalomania of the modernist architects, their evangelical zeal on behalf of what turned out to be, and could have been known in advance to be, an aesthetic and moral catastrophe, is here fully described. The story is more convoluted than I, not being an historian, had appreciated; Professor Curl conducts us deftly through the thickets of influences of which I, at least, had been ignorant. But the rapid rise and complete triumph of modernism throughout the world, so that an office block in Caracas should be no different from one in Bombay or Johannesburg, is to me still mysterious, considering that its progenitors were a collection of cranks and crackpots who wrote very badly and whose ideas would have disgraced an intelligent sixth-former. I do not see how anyone could read Corbusier, for example (and I have read a fair bit of him), without conceiving an immediate and complete contempt for him as a man, thinker and writer. He has two kinds of sentence, the declamatory falsehood and the peremptory order without reasons given. How anyone could have taken his bilge seriously is by far the most important enquiry that can be made about him.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Architectural Dystopia: A Book Review”, New English Review, 2018-10-04.

September 19, 2024

D-Day Tanks: Operation Overlord’s Strangest Tanks

The Tank Museum

Published Jun 7, 2024An opposed beach landing is the most difficult and dangerous military operation it is possible to undertake. Anticipating massive casualties in the Normandy Landings, the British Army devised a series of highly specialized tanks to solve some of the problems – Hobart’s Funnies.

Named after General Sir Percy Hobart, commander of their parent unit, 79th Armoured Division, the Funnies included a mine clearing tank – the Sherman Crab, a flamethrower – the Churchill Crocodile and the AVRE – Assault Vehicle Royal Engineers which could lay bridges and trackways, blow up fortifications and much else besides.

In this video, Chris Copson looks at surviving examples of the Funnies and assesses their effectiveness on D Day and after.

00:00 | Introduction

01:24 | Operation Overlord

03:02 | Lessons from the Dieppe Raid

05:31 | The Sherman DD

07:21 | Exercise Smash

14:38 | Sherman Crab

17:38 | The AVRE

19:47 | Churchill Crocodile

23:15 | Did the Funnies Work?

28:49 | ConclusionThis video features archive footage courtesy of British Pathé.

#tankmuseum #d-day #operationoverlord

September 17, 2024

Parisian Needlefire Knife-Pistol Combination

Forgotten Weapons

Published Nov 30, 2017Combination knife/gun weapons have been popular gadgets for literally hundreds of years, and this is one of the nicest examples I have yet seen. This sort of thing is usually very flimsy, and not particularly well made. This one, however, has a blade which locks in place securely and would seem to be quite practical. The firearm part is also unique, in that it uses a needlefire bolt-action mechanism. This is a tiny copy of the French military Chassepot system, complete with intact needle and obturator.

And, of course, since it is French the trigger is a corkscrew.

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

September 3, 2024

The End of World War Two – WW2 – Week 314B – September 2, 1945

World War Two

Published 2 Sep 2024The Japanese sign the official document of surrender and the Second World War is over. There are still some Japanese garrisons yet to surrender, but they begin doing so one after the other. However, war is not over — and there is serious foreboding for future events in places like Vietnam and China — where Mao Zedong is meeting with Chiang Kai-Shek, even as Josef Stalin lurks in the background to secure Soviet interests no matter which Chinese regime comes out on top.

00:00 Intro

00:59 Vietnam Declares Independence

04:04 The Importance Of Manchuria

06:28 Japan’s Surrender

11:22 The Final Surrenders

13:18 Casualties

15:50 The End

(more…)

August 30, 2024

The urge to power

At Mindset Shifts, Barry Brownstein explains why the urge to gain power over other people is particularly strong in those who don’t have meaningful lives of their own:

King Louis XIV, the “Sun King”.

Portrait by Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659-1743) sometime in 1700 or 1701 from the Louvre via Wikimedia Commons.

One of my more memorable exchanges with a student came in a principles of economics class. Part of the assignment for that week was chapters from Matt Ridley’s The Rational Optimist. Ridley compared the living standards of an average worker today with those of The Sun King, Louis XIV, in 1700. Some of my more ahistorical students were incredulous at Ridley’s description of the grinding poverty of the average person just a few centuries ago.

The King had an opulent lifestyle compared to others. Louis had an astonishing 498 workers preparing each of his meals. Yet his standard of living was still a fraction of what we experience today.

Ridley outlined the miracles of specialization and exchange in our time — an everyday cornucopia at the supermarket, modern communications and transportation, clothing to suit every taste. If we remove our blinders and see how many individuals provide services to us, Ridley concludes we have “far more than 498 servants at [our] immediate beck and call”.

Then, the memorable exchange occurred. One student shared that he would prefer to live in 1700, if he had more money than others and power over them. My first reaction was amusement; I thought the student was practicing his deadpan humor skills. He wasn’t. For him, having power was an attribute of a meaningful life.

If only my student’s mindset were an aberration.

During the reign of Louis XIV, French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal diagnosed why some lust for power. In his Pensées, Pascal wrote, “I have often said that the sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room”. Pascal explained that, out of the inability to sit alone, arises the human tendency to seek power as a diversion.

Pascal asks us to imagine a king with “all the blessings with which you could be endowed”. A king, Pascal told us, if he has no “diversions” from his thinking, will “ponder and reflect on what he is”. Pascal’s hypothetical king will be miserable because he “is bound to start thinking of all the threats facing him, of possible revolts, finally of inescapable death and disease”.

“What people want is not the easy peaceful life that allows us to think of our unhappy condition.” That is why “war and high office are so popular”, Pascal argued.

Pascal argues individuals seek to be “diverted from thinking of what they are”. I would argue a better choice of words is what they have made of themselves.

I’ll let the reader decide how many modern politicians Pascal’s ideas apply to. With Pascal’s insight, we understand why conflict is a feature of politics and not a bug.

Pascal spares no one’s feelings. Some “seek external diversion and occupation, and this is the result of their constant sense of wretchedness”. For them, “rest proves intolerable because of the boredom it produces. [They] must get away from it and crave excitement.”

Let that sink in. A person able to exercise coercive power can use their morally undeveloped “wretched” mind to create endless misery for others merely because exercising power distracts them from their failures as human beings.

August 29, 2024

Pavel Durov’s arrest isn’t for a clear crime, it’s for allowing everyone access to encrypted communications services

J.D. Tuccille explains the real reason the French government arrested Pavel Durov, the CEO of Telegram:

It’s appropriate that, days after the French government arrested Pavel Durov, CEO of the encrypted messaging app Telegram, for failing to monitor and restrict communications as demanded by officials in Paris, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg confirmed that his company, which owns Facebook, was subjected to censorship pressures by U.S. officials. Durov’s arrest, then, stands as less of a one-off than as part of a concerted effort by governments, including those of nominally free countries, to control speech.

“Telegram chief executive Pavel Durov is expected to appear in court Sunday after being arrested by French police at an airport near Paris for alleged offences related to his popular messaging app,” reported France24.

A separate story noted claims by Paris prosecutors that he was detained for “running an online platform that allows illicit transactions, child pornography, drug trafficking and fraud, as well as the refusal to communicate information to authorities, money laundering and providing cryptographic services to criminals”.

Freedom for Everybody or for Nobody

Durov’s alleged crime is offering encrypted communications services to everybody, including those who engage in illegality or just anger the powers that be. But secure communications are a feature, not a bug, for most people who live in a world in which “global freedom declined for the 18th consecutive year in 2023”, according to Freedom House. Fighting authoritarian regimes requires means of exchanging information that are resistant to penetration by various repressive police agencies.

“Telegram, and other encrypted messaging services, are crucial for those intending to organise protests in countries where there is a severe crackdown on free speech. Myanmar, Belarus and Hong Kong have all seen people relying on the services,” Index on Censorship noted in 2021.

And if bad people occasionally use encrypted apps such as Telegram, they use phones and postal services, too. The qualities that make communications systems useful to those battling authoritarianism are also helpful to those with less benign intentions. There’s no way to offer security to one group without offering it to everybody.

As I commented on a post on MeWe the other day, “Somehow the governments of the west are engaged in a competition to see who can be the most repressive. Canada and New Zealand had the early lead, but Australia, Britain, Germany, and France have all recently moved ahead in the standings. I’m not sure what the prizes might be, but I strongly suspect “a bloody revolution” is one of them (if not all of them).”

August 25, 2024

After Wittmann’s Tiger Tank Rampage – The Fight back at Villers-Bocage

The Tank Museum

Published May 10, 2024 16 productsMichael Wittmann’s rampage at Villers-Bocage was just the start of a fight that was far from the great victory the Germans would claim it to be. At 0930 on 13 June 1944, in the chaos that followed Wittmann’s fortuitous lunge into the British column, the men of the 4th County of London Yeomanry lick their wounds and set up their defences. They’ve been given the order to hold the Villers-Bocage at all costs — and will soon be fighting for their lives against a superior German force.

By the end of the day, a young Lt. Bill Cotton will have earned the Military Cross and a promotion to Captain. His Sergeant will earn a Military Medal and his Corporal a Distinguished Conduct Medal … In the hype surrounding the career of Michal Wittmann, has the role of Bill Cotton and his troop been overlooked? Was he the real hero of Villers-Bocage?

Watch our video on Wittmann’s Tiger Tank Rampage:

• Wittmann’s Tiger Tank Rampage | Ville…00:00 | Introduction

00:56 | Aftermath of Wittmann’s Rampage

01:48 | Reconnaissance and Reinforcements

03:24 | Lt. Bill Cotton

05:26 | Bayerlein Strikes

07:05 | Three Tigers Taken Out

08:18 | The Heroes of Villers-Bocage

10:42 | Bramall’s Ingenuity

14:48 | The End of the Assault

16:16 | ConclusionThis video features footage courtesy of British Pathe.

#tankmuseum #tankactions #villersbocage

August 20, 2024

You’re the Top! A History of the Top Hat

HatHistorian

Published Nov 21, 2021A short history of one of the most recognizable and formal hats of our time: the top hat!

Version française ici:

• Le top du top: l’histoire du Haut-de-…With thanks to Norman Caruso for advice on how to get me started on youtube. Please check out his channel

The first top hat belonged to my great grandfather and is the better part of a century old.

The collapsible top hat comes from from Delmonico Hatter https://www.delmonicohatter.com/Title sequence designed by Alexandre Mahler

am.design@live.comThis video was done for entertainment and educational purposes. No copyright infringement of any sort was intended.

August 18, 2024

.30-06 M1918 American Chauchat – Doughboys Go to France

Forgotten Weapons

Published May 4, 2024When the US entered World War One, the country had a grand total of 1,453 machine guns, split between four different models. This was not a useful inventory to equip even a single division headed for France, and so the US had to look to France for automatic weapons. In June 1917 Springfield Armory tested a French CSRG Chauchat automatic rifle, and found it good enough to inquire about making an American version chambered for the .30-06 cartridge. This happened quickly, and after testing in August 1917, a batch of 25,000 was ordered. Of these, 18,000 were delivered and they were used to arm several divisions of American troops on the Continent.

Unfortunately, the American Chauchat was beset by extraction problems. These have today be traced to incorrectly cut chambers, which were slightly too short and caused stuck cases when the guns got hot. It is unclear exactly what caused the problem, but the result was that most of the guns were restricted to training use (as best we can tell today), and exchanged for French 8mm Chauchats when units deployed to the front. Today, American Chauchats are extremely rare, but also very much underappreciated for their role as significant American WWI small arms.

(more…)

August 16, 2024

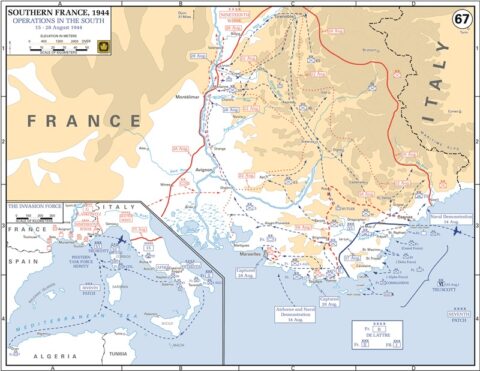

“Operation Dragoon … was described by Adolf Hitler as the worst day of his life”

The “other” D-Day landing in France that few people know much about: Operation Dragoon.

Often referred to as “the other D-Day”, Op Dragoon ran until 14 September 1944 and was a pivotal turning point in the Second World War.

Op Dragoon was a huge and complex operation by land, sea and air that liberated nearly two-thirds of France by linking up with troops from the Normandy invasion on 11 September and pushing the German forces right back to their frontier.

It also secured the ports of Marseilles and Toulon so Allied troops could flood into France.

This was a bitter blow for Hitler, who during conversations with his generals that were discovered in records written in shorthand, said: “The 15th of August was the worst day of my life”.

Dr Peter Caddick-Adams, a military historian and defence analyst, spoke to BFBS Forces News about Operation Dragoon, a largely French/American operation with support from countries including the UK and Canada.

He said: “It set the victory over Germany firmly on its way — and the end of the Second World War couldn’t really have been achieved without Operation Dragoon.

“This is the D-Day that you’ve never heard of.

“Originally there was planned to be two invasions of France on the same day — in Normandy and on the south coast of France along the Riviera.

“It was found that we didn’t have enough landing craft to do both at the same time simultaneously.”

It also didn’t help that Winston Churchill was against the idea and tried to cancel the operation.

The Prime Minister wanted the Italian campaign to remain dominant and was worried Dragoon would take troops and other resources away from Italy.

However, despite his best efforts, the Americans and French prevailed and Operation Dragoon went ahead.

Initially, the operation was given the codename Anvil, because Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy, was originally going to be called Sledgehammer.

The plan was for Germany’s armed forces to be smashed between the hammer and the anvil.

Churchill never changed his opinion about the operation despite its eventual success, as Dr Caddick-Adams explained: “At the last minute Churchill had the name changed to Dragoon and, legend has it, because he felt he was being dragooned into an operation that he didn’t want to undertake”.

August 13, 2024

The Original Secret History

Tom Ayling

Published Apr 28, 2024This is the story of Procopius’s Secret History Of Justinian – originally written around 550, but not published until 1623.

In this video we look at how Procopius wrote the text, how it survived, almost unknown, for 1,000 years, how it came to be published in the 1620s, and the extraordinary ramifications when it was.

00:00 Introduction

00:44 The Original Composition Of The Secret History

02:40 The Survival Of The Text In Greek Manuscripts

05:56 The Rediscovery And Publication Of The Secret History

08:23 Secret Histories Go ViralTo learn more about Secret Histories, sign up to receive my catalogue of rare books devoted to the subject – https://www.tomwayling.co.uk/register

I couldn’t have made this video without the help of two works in particular. The first is Brian Croke’s magisterial Procopius: From Manuscripts To Books: 1400-1850. The second is The Secret History In Literature, 1660-1820 which is edited by Rebecca Bullard and Rachel Carnell.

My name’s Tom and I’m an antiquarian bookseller – you can browse the books I have for sale on my website: https://www.tomwayling.co.uk/