CDR Salamander is pleased at the way the CBS team for 60 Minutes presented their US Navy coverage in a recent show:

A regular topic of conversation here […] is the lack of discussion in the public space about the importance of a strong Navy to our republic’s economic and military security. Sure, inside our salons, slack channels, and email threads we talk to each other a lot, but we seem to have a hard time getting our message out to the general public.

Sunday night’s 60 Minutes was an exception to the rule. There is a lot of credit to go around here. First of all, you have to give credit to the 60 Minutes team fronted by Norah O’Donnell and lead producers Keith Sharman and Roxanne Feitel. This two-segment effort was not just on a topic we all are interested in, it was just plain good journalism.

Sure, I have a nit to pic here and there, but that is just my nature. Perfect? No … but it is one of the best bits of solid, down the middle journalism about our Navy and its challenges I have seen from a major network for a long time.

If you missed it, CBS has published the video and transcript that I’m going to pull some bits from below for conversation.

The second segment was more meatier than the first, but the first is important. It isn’t just where Big Navy got a chance to make a run at media capture with the “C-2 to the Big Deck at sea” show that we all love, but it will introduce many people to someone who is very good at his job and representing the Navy, Admiral Samuel Paparo, USN.

He gets your attention early by, even though clearly well prepared and sticking to scripted talking points and marketing pitches here and there of questionable utility, he also spoke in blunt terms in a way we don’t hear enough in venues such as this:

Admiral Samuel Paparo commands the U.S. Pacific Fleet, whose 200 ships and 150,000 sailors and civilians make up 60% of the entire U.S. Navy. We met him last month on the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz deployed near the U.S. territory of Guam, southeast of Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China, or PRC.

Norah O’Donnell: You’ve been operating as a naval officer for 40 years. How has operating in the Western Pacific changed?

Admiral Samuel Paparo: In the early 2000s the PRC Navy mustered about 37 vessels. Today, they’re mustering 350 vessels.

…

60 Minutes has spent months talking to current and former naval officers, military strategists and politicians about the state of the U.S. Navy. One common thread in our reporting is unease, both about the size of the U.S. fleet and its readiness to fight. The Navy’s ships are being retired faster than they’re getting replaced, while the navy of the People’s Republic of China or PRC, grows larger and more lethal by the year. We asked the commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, Admiral Samuel Paparo, about this on our visit to the USS Nimitz, the oldest aircraft carrier in the Navy.

Admiral Samuel Paparo: We call it the Decade of Concern. We’ve seen a tenfold increase in the size of the PRC Navy.

Norah O’Donnell: Technically speaking, the Chinese now have the largest navy in the world, in terms of number of ships, correct?

Admiral Samuel Paparo: Yes. Yes.

Norah O’Donnell: Do the numbers matter?

Admiral Samuel Paparo: Yes. As the saying goes, “Quantity has a quality all its own.”

This is exactly how the answer needs to be delivered. No squish, no excessive spin — acknowledge the reality of where we are.

More of this from more senior leaders.

There was some subtlety as well. When he first said this, about 10-seconds later I decided to rewind to listen to it again.

Norah O’Donnell: And if China invades Taiwan, what will the U.S. Navy do?

Admiral Samuel Paparo: It’s a decision of the president of the United States and a decision of the Congress. It’s our duty to be ready for that. But the bulk of the United States Navy will be deployed rapidly to the Western Pacific to come to the aid of Taiwan if the order comes to aid Taiwan in thwarting that invasion.

Norah O’Donnell: Is the U.S. Navy ready?

Admiral Samuel Paparo: We’re ready, yes. I’ll never admit to being ready enough.

Did you catch that? He can’t say, “We’re not ready” as if the call comes, we can and will execute what we are tasked … and initially will be ready to do what we can with the reduced numbers we have … but everyone knows there is a huge asterisk next to “ready”.

We don’t have enough escort ships. We don’t have enough VLS tubes. We don’t have a large enough airwing with long enough legs. We don’t have enough reliable and robust tanking. We don’t have much of a bench … so, we are “ready” – but not even close to being “ready enough”. A subtle distinction with not so subtle implications.

We also need to give a nod to our Navy for not having only the 4-stars talk to CBS. LCDR David Ash, USN got some good face time with the camera, and his fellow LCDR Matthew Carlton, USN blessed us with his superb deployment stash.

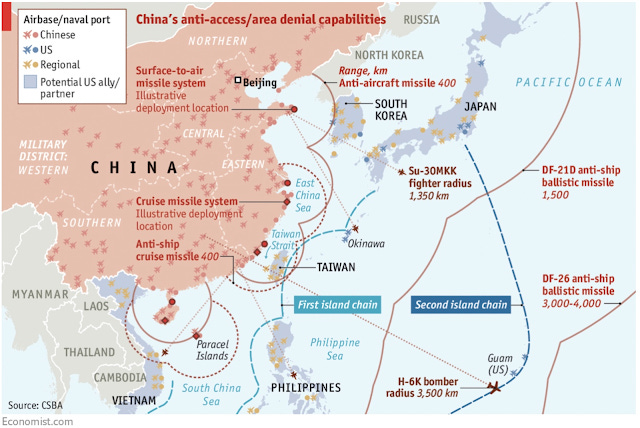

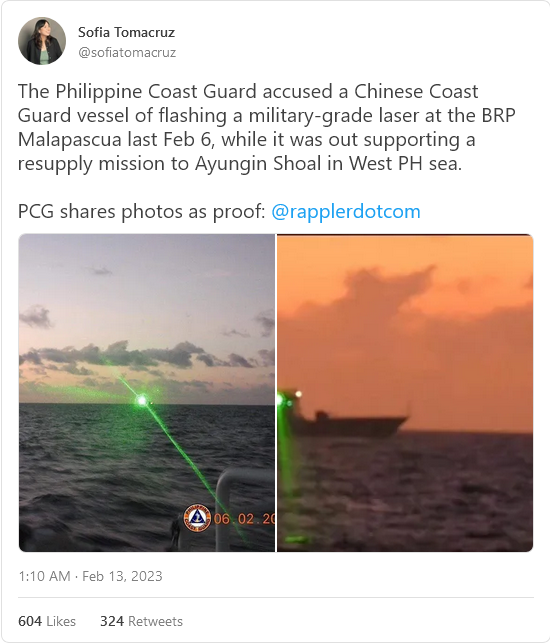

60 Minutes‘ graphics department also gets credit for the video that the pic at the top of this post is a screen capture of.

Add “PLARF” to you handy list of military acronyms for future reference:

There was another point where Admiral Paparo put a marker down that someone can pick up and run with … hey, I think I’ll do that now;

Norah O’Donnell: How much do you worry about the PLA Rocket Force?

Admiral Samuel Paparo: I worry. You know, I — I’d be a fool to not worry about it. Of course I worry about the PLA Rocket Force. And of course I work every single day to develop the tactics and the techniques and the procedures to counter it, and to continue to develop the systems that can also defend– against them.

Norah O’Donnell: About how far are we from mainland China?

Admiral Samuel Paparo: Fifteen hundred nautical miles.

Norah O’Donnell: They can hit us.

Admiral Samuel Paparo: Yes they can. If they’ve got the targeting in place, they could hit this aircraft carrier. If I don’t want to be hit, there’s something I can do about it.

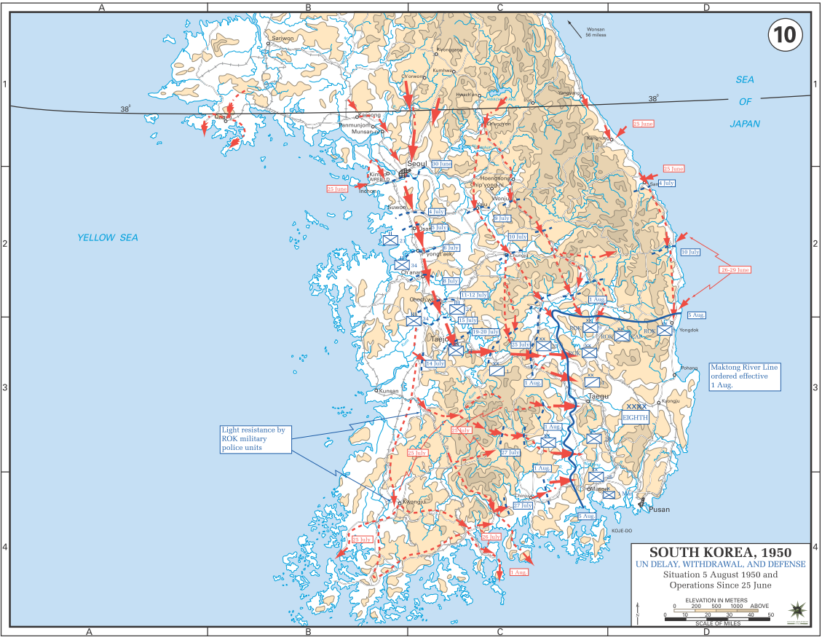

Ahhhhh, yes. Time to bring back one of my favorite graphics.

Draw a 1,500nm circle from the PLARF launch sites and look at what land based airfields, bases, depots and facilities of all sorts are located under that threat. They cannot move. A navy and sea based facilities can.

Undersold point, but Paparo is leaving it there for you to run with.