I missed this article by Kay S. Hymowitz when it was published by City Journal a couple of weeks back:

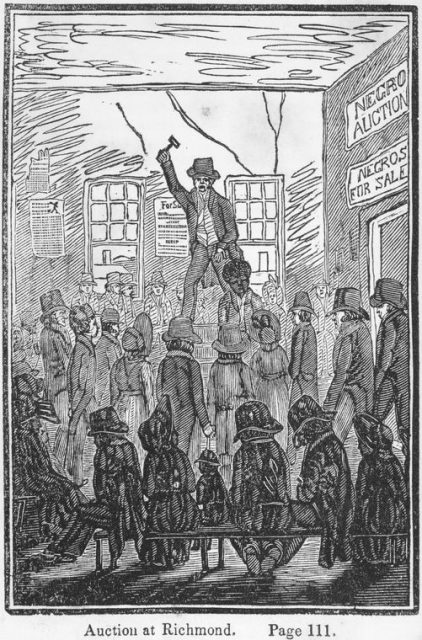

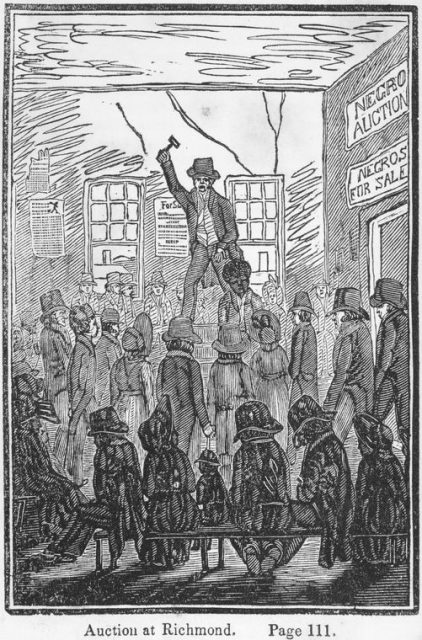

Auction at Richmond. (1834)

“Five hundred thousand strokes for freedom ; a series of anti-slavery tracts, of which half a million are now first issued by the friends of the Negro.” by Armistead, Wilson, 1819?-1868 and “Picture of slavery in the United States of America. ” by Bourne, George, 1780-1845

New York Public Library via Wikimedia Commons.

… slavery was a mundane fact in most human civilizations, neither questioned nor much thought about. It appeared in the earliest settlements of Sumer, Babylonia, China, and Egypt, and it continues in many parts of the world to this day. Far from grappling with whether slavery should be legal, the code of Hammurabi, civilization’s first known legal text, simply defines appropriate punishments for recalcitrant slaves (cutting off their ears) or those who help them escape (death). Both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament take for granted the existence of slaves. Slavery was so firmly established in ancient Greece that Plato could not imagine his ideal Republic without them, though he rejected the idea of individual ownership in favor of state control. As for Rome, well, Spartacus, anyone?

In the ancient world, slaves were almost always captives from the era’s endless wars of conquest. They were forced to do all the heavy labor required for building and sustaining cities and towns: clearing forests; building roads, temples, and palaces; digging and transporting stone; hoeing fields; rowing galley ships; and marching to almost-certain death in the front line of battle. Women (and often enough boy) slaves had the task of servicing the sexual appetites of their masters. None of that changed with the arrival of a new millennium. Gaelic tribes took advantage of the fall of the Roman Empire to raid the west coast of England and Wales for strong bodies; one belonged to a 16-year-old later anointed St. Patrick, patron saint of Ireland. “In the slavery business, no tribe was fiercer or more feared than the Irish,” writes Thomas Cahill in How the Irish Saved Civilization.

Today, of course, the immorality of slave-owning is as clear as day. But in the premodern world, no neat division existed between evil slaveowners and their innocent victims. Once the Vikings arrived in their longboats in the 700s, the Irish enslavers found themselves the enslaved. Slavery became the commanding height of the Viking economy; Norsemen raided coastal villages across Europe and brought their captives to Dublin, which became one of the largest slave markets of the time. The Vikings thought of their slaves as more like cattle than people; the unlucky victims had to sleep alongside the domestic animals, according to the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. Norsemen rounded up captured Irish men and women to settle the desolate landscape of Iceland; scientists have found Irish DNA in present-day Icelanders, a legacy of that time. The Slavic tribes in Eastern Europe were an especially fertile supplier for Viking slave traders as well as for Muslim dealers from Spain: their Latin name gave us the word slave. Slavs were evidently not deterred by the misery they must have suffered; when Viking power waned by the twelfth century, the Slavs turned around and enslaved Vikings as well as Greeks.

Slavery was a normal state of affairs well beyond the territory we now call Europe. The Mayans had slaves; the Aztecs harnessed the labor of captives to build their temples and then serve as human sacrifices at the altars they had helped construct. The ancient Near East and Asia Minor were chockfull of slaves, mostly from East Africa. According to eminent slavery scholar Orlando Patterson, East Africa was plundered for human chattel as far back as 1580 BC. Muhammad called for compassion for the enslaved, but that didn’t stop his followers from expanding their search for chattel beyond the east coast into the interior of Africa, where the trade flourished for many centuries before those first West Africans arrived in Jamestown. Throughout that time, African kings and merchants grew rich from capturing and selling the millions of African slaves sent through the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean to Persians and Ottomans.

From the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries, the North African Barbary coast was a hub for “white slavery.” This episode was relatively short-lived in the global history of slavery, but one with overlooked impact on Western culture. Around 1619, just as the first Africans were being sailed from the African coast to Jamestown, Algerian and Tunisian pirates, or “corsairs” as they were known, were using their boats to raid seaside villages on the Mediterranean and Atlantic for slaves who happened in this case to be white. In 1631, Ottoman pirates sacked Baltimore on the southern coast of Ireland, capturing and enslaving the villagers. Around the same time, Iceland was raided by Barbary corsairs who took hundreds of prisoners, selling them into lifetime bondage.