Sabaton History

Published 6 Apr 2023By the middle of the Great War, several nations had begun to experiment with shock troops, and Germany was one of them. The Sturmtruppen were a revolution on the battlefield, for sure, but what did they actually do? What equipment did they carry and use? What were the men actually like? Today we’ll look at all that.

(more…)

April 7, 2023

Stormtroopers – The German Elite of WW1 – Sabaton History 119

Manpower shortages in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) during WW1

This is an excerpt from Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry, an unpublished book by the late John Sayen which is being serialized at Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook on Substack. While I haven’t read a lot on the AEF, as I’ve concentrated much more on the Canadian Corps as part of the British Expeditionary Force, I was aware that the American divisions were organized quite differently from either British or French equivalents. The significanly larger division organization — 28,000 men compared to about half that in other allied armies — was intended to give US Army units greater staying power in combat, but it didn’t work out as planned for many reasons:

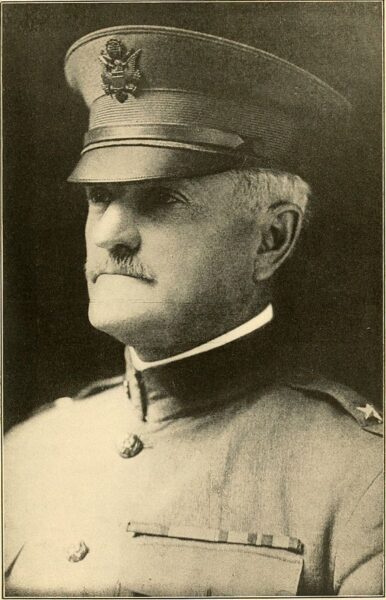

General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces in France during the First World War.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The basic tactical concept behind the square AEF divisions under which the two regiments holding the division’s front line could be relieved by two more regiments to their rear was seriously undermined. The two regiments that were supposed to be resting were the ones that had to man all the work details. When it came time for them to relieve the front-line regiments it was, as historian Allan Millett described it, often a question “of replacing exhausted troops who had suffered casualties with exhausted troops who had not”.

It had certainly not been intended that the infantry serve as labor troops. Such tasks were supposed to have been carried out by separate regiments of pioneers modeled on those used by the French. In the French Army, pioneer regiments were lightly armed infantry serving under corps and army headquarters. They tended to consist of older men and were not the elite assault troops that filled the pioneer platoons in the infantry regiments. Though they could fight when necessary, their main function was to furnish the bulk of the semi-skilled and unskilled labor in the forward areas.

In imitation of this system the War Department raised 37 AEF pioneer regiments. These were organized as AEF infantry regiments without machinegun companies or sapper-bomber, pioneer, or one-pounder gun platoons. Only two of the 29 pioneer regiments to reach France did so before the last three months of the war. One regiment was supposed to go to each army corps and several to each army. However, the AEF pioneers proved to be so badly trained and led (even by AEF standards) that after front line service involving a mere 241 battle casualties most of the pioneers were pulled out of combat to serve as unarmed laborers far to the rear.

It wasn’t just combat casualties that reduced US divisional effectiveness:

Early planning had called for one third of all divisions to serve as replacement depots or field-training units charged with keeping the remaining combat divisions filled with men. The system broke down, however, as heavy losses forced the intended depot divisions to be used as combat units instead. Only six of the 42 AEF divisions to reach France before the Armistice (three more arrived soon afterwards) actually served as replacement or training depots instead of the 14 that were needed.

As an emergency measure, five combat divisions, and later two of the depot divisions, were skeletonized to immediately create urgently needed replacements but, of course, this rendered them useless for either combat or depot duty. Another division had to be fragmented to provide men for rear area support duties and yet another was broken up to flesh out three French divisions. Even in February 1918, (before the AEF had seen serious combat) the four combat divisions in the AEF I Corps were 8,500 men short (mostly in their infantry regiments). The 41st Division, which was the corps’ depot division and charged with supplying those missing men was itself 4,500 men short. By early October 1918, AEF combat units needed 80,000 replacements but only 45,000 were expected before 1 November. At the end of October, the total shortfall had reached 119,690, including 95,303 infantrymen and 8,210 machine gunners. Only 66,490 replacement infantrymen and machine gunners would be available any time soon. For most of the war, AEF combat divisions were typically short by 4,000 men. After August 1918, even divisions fresh from the United States usually needed men. Too many divisions had been organized too quickly.

Of course, the root cause of the manpower problem was even more basic. Men were being used up faster than they could be replaced. The AEF suffered most of its battle casualties between 25 April and 11 November 1918, a period of less than seven months. These combat losses amounted to between 260,000 and 290,000 officers and men, of whom some 53,000 were killed in action or died of their wounds. The rest were wounded or gassed but 85% of these subsequently returned to duty. About 4,500 AEF prisoners of war were repatriated after the Armistice. Five thousand others became victims of “shell shock.” Accidental casualties, including those known to have been caused by “friendly fire” (total friendly fire losses must have been considerable, given the poor state of infantry-artillery coordination), or disease or self-inflicted wounds, far exceeded those sustained in battle.

Two thirds of the more than 125,000 Army and Marine Corps deaths between April 1917 and May 1919 occurred overseas and nearly half (57,000) were from disease. Pneumonia and influenza-pneumonia, which produced the infamous “swine flu” epidemic of 1918, were the chief killers but many victims who became ill before the Armistice did not actually die until after it. Between 14 September and 8 November 1918 some 370,000 cases were reported in the United States alone. Within less than two years between one quarter and one third of the men serving in the US Army had died or became temporarily or permanently disabled by battle, disease, accident, or misconduct. Had such losses continued, the United States might soon have begun to experience the same war weariness and manpower “burnout” that had been plaguing the British, French, and Germans.

With regard to the infantry, the woes of the AEF replacement and training system were much increased by the prevailing belief that because an infantryman needed few technical skills he had little to learn and could be quickly and easily trained from very average human material. Technical arms such as the engineers, signal corps, artillery, and, more significantly, the air corps got the pick of the AEF’s manpower.

The infantry soon became the repository for those deemed unfit for anything better. Many infantrymen saw themselves, and were seen, as cannon fodder. Morale and cohesion were further undermined by the practice of stripping new divisions of men (often before they had even left the United States) to fill older ones. The better men and officers avoided infantry duty to seek less demanding “technical” jobs. Of course, training suffered grievously.

As demands for replacements became more insistent, men who supposedly had received several months’ training were appearing in the front lines not knowing how to load their rifles. Others proved to be recent immigrants who could not speak English. Infantrymen of small physique who might have rendered useful service in non-infantry roles, soon collapsed under the physical burdens placed on them and became liabilities rather than assets. Losses among even good infantry were heavy enough but mediocre infantry melted away at an astonishing rate. Indiscipline, disorganization, and ignorance inevitably increased losses by what must have seemed like a couple of orders of magnitude. These losses were likely to be replaced, if at all, by men of even lower caliber.

Straggling was an especially pernicious problem, which the military police had only limited success in controlling. Even more than actual casualties, it caused some units to simply evaporate. During the Meuse-Argonne offensive, for example, one division reported that it was down to only 1,600 effective men. However, soon after it arrived at a rest area, it reported 8,400 men in its infantry regiments alone.

How to Make a Shaker Candle Box | Episode 2

Paul Sellers

Published 18 Nov 2022With the dovetails all fitting, we are ready to clean up the inside faces of the box, ready for gluing the corners together. It’s a systematic process that minimises the risk of messing up.

Lots of tricks of the trade for gluing up and checking the whole for squareness, etc. Planing out any unevenness ensures a pristine finish, and we definitely follow a process that gives top-notch results.

The lid and bottom of the box are both rounded over, and the simplest thing is that we only need one tool, the #4 plane, to achieve amazing results. The final stage is to glue the bottom onto the box and prepare the lid for hingeing.

——————–

(more…)

QotD: The effluvium of the university’s overproduction of progressive “elites”

By the late 1990s the rapid expansion of the universities came to a halt, especially in the humanities. Faculty openings slowed or stopped in many fields. Graduate enrollment cratered. In my own department in 10 years we went from accepting over a hundred students for graduate study to under 20 for a simple reason. We could not place our students. The hordes who took courses in critical pedagogy, insurgent sociology, gender studies, radical anthropology, Marxist cinema theory, and postmodernism could no longer hope for university careers.

What became of them? No single answer is possible. They joined the work force. Some became baristas, tech supporters, Amazon staffers and real estate agents. Others with intellectual ambitions found positions with the remaining newspapers and online periodicals, but most often they landed jobs as writers or researchers with liberal government agencies, foundations, or NGOs. In all these capacities they brought along the sensibilities and jargon they learned on campus.

It is the exodus from the universities that explains what is happening in the larger culture. The leftists who would have vanished as assistant professors in conferences on narratology and gender fluidity or disappeared as law professors with unreadable essays on misogynist hegemony and intersectionality have been pushed out into the larger culture. They staff the ballooning diversity and inclusion commissariats that assault us with vapid statements and inane programs couched in the language they learned in school. We are witnessing the invasion of the public square by the campus, an intrusion of academic terms and sensibilities that has leaped the ivy-covered walls aided by social media. The buzz words of the campus — diversity, inclusion, microaggression, power differential, white privilege, group safety — have become the buzz words in public life. Already confusing on campus, they become noxious off campus. “The slovenliness of our language”, declared Orwell in his classic 1946 essay, “Politics and the English Language“, makes it “easier for us to have foolish thoughts.”

Orwell targeted language that defended “the indefensible” such as the British rule of India, Soviet purges and the bombing of Hiroshima. He offered examples of corrupt language. “The Soviet press is the freest in the world.” The use of euphemisms or lies to defend the indefensible has hardly disappeared: Putin called the invasion of Ukraine “a special military operation”, and anyone calling it a “war” or “invasion” has been arrested.

But today, unlike in 1946, political language of Western progressives does not so much as defend the indefensible as defend the defendable. This renders the issue trickier than when Orwell broached it. Apologies for criminal deeds of the state denounce themselves. Justifications for liberal desiderata, however, almost immunize themselves to objections. If you question diversity mania, you support Western imperialism. Wonder about the significance of microaggression? You are a microaggressor. Have doubts about an eternal, all-inclusive white supremacy? You benefit from white privilege. Skeptical about new pronouns? You abet the suicide of fragile adolescents.

Russell Jacoby, “The Takeover”, Tablet, 2022-12-19.

April 6, 2023

Make a Router Plane FAST with this affordable kit // The Compass Rose Router

Rex Krueger

Published 5 Apr 2023More about the Router Plane Kit:

The Compass Rose Router Plane Kit is your fastest and most affordable path to a quality hand router. Long before Stanley invented the metallic router plane, artisans made their own routers from wood. These shop-made tools were effective and affordable for working craftspeople. Now, Compass Rose Toolworks is reinventing the wooden hand router. Our Router Plane has an extra-large hardwood body contoured for comfort. Instead of a tricky mortise and wedge, our blades are secured with a large brass thumb-screw. Our kit includes two blades in ½” and ¼” (13mm/6mm) widths as well as a pair of threaded inserts and an installation tool. The build is straightforward and can be completed in a single afternoon (plus time for the glue to dry.) We want you to be successful in this build, so we’ve also created a FREE assembly guide and a complete video tutorial on the build. These materials are available to anyone, even if you haven’t bought the kit yet.

Each kit includes:

– American ash body in two pieces for easy assembly.

– Two Cr-V blades, heat treated and ground, ready for final honing.

– Solid brass thumb-screw with 2 inserts, so you’ve got a backup.

– Insert installation tool (steel bolt and 2 nuts).

– Instant access to the PDF assembly guide and video tutorial.

(more…)

Japan is weird, example MCMLXIII

John Psmith reviews MITI and the Japanese Miracle by Chalmers Johnson:

I’ve been interested in East Asian economic planning bureaucracies ever since reading Joe Studwell’s How Asia Works (briefly glossed in my review of Flying Blind). But even among those elite organizations, Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) stands out. For starters, Japanese people watch soap operas about the lives of the bureaucrats, and they’re apparently really popular! Not just TV dramas; huge numbers of popular paperback novels are churned out about the men (almost entirely men) who decide what the optimal level of steel production for next year will be. As I understand it, these books are mostly not about economics, and not even about savage interoffice warfare and intraoffice politics, but rather focus on the bureaucrats themselves and their dashing conduct, quick wit, and passionate romances … How did this happen?

It all becomes clearer when you learn that when the Meiji period got rolling, Japan’s rulers had a problem: namely, a vast, unruly army of now-unemployed warrior aristocrats. Samurai demobilization was the hot political problem of the 1870s, and the solution was, well … in many cases it was to give the ex-samurai a sinecure as an economic planning bureaucrat. Since positions in the bureaucracy were often quasi-hereditary, what this means is that in some sense the samurai never really went away, they just hung up their swords — frequently literally hung them up on the walls of their offices — and started attacking the problem of optimal industrial allocation with all the focus and fury that they’d once unleashed on each other. According to Johnson, to this day the internal jargon of many Japanese government agencies is clearly and directly descended from the dialects and battle-codes of the samurai clans that seeded them.

This book is about one such organization, MITI, whose responsibilities originally were limited to wartime rationing and grew to encompass, depending who you ask, the entire functioning of the Japanese government. Because this is the buried lede and the true subject of this book: you thought you were here to read about development economics and a successful implementation of the ideas of Friedrich List, but you’re actually here to read about how the entire modern Japanese political system is a sham. This suggestion is less outrageous than it may sound at first blush. By this point most are familiar with the concept of “managed democracy,” wherein there are notionally competitive popular elections, culminating in the selection of a prime minister or president who’s notionally in charge, but in reality some other locus of power secretly runs things behind the scenes.

There are many flavors of managed democracy. The classic one is the “single-party democracy”, which arises when for whatever reason an electoral constituency becomes uncompetitive and returns the same party to power again and again. Traditional democratic theory holds that in this situation the party will split, or a new party will form which triangulates the electorate in just such a way that the elections are competitive again. But sometimes the dominant party is disciplined enough to prevent schisms and to crush potential rivals before they get started. The key insight is that there’s a natural tipping-point where anybody seeking political change will get a better return from working inside the party than from challenging it. This leads to an interesting situation where political competition remains, but moves up a level in abstraction. Now the only contests that matter are the ones between rival factions of party insiders, or powerful interest groups within the party. The system is still competitive, but it is no longer democratic. This story ought to be familiar to inhabitants of Russia, South Africa, or California.

The trouble with single-party democracies is that it’s pretty clear to everybody what’s going on. Yes, there are still elections happening, there may even be fair elections happening, and inevitably there are journalists who will point to those elections as evidence of the totally-democratic nature of the regime, but nobody is really fooled. The single-party state has a PR problem, and one solution to it is a more postmodern form of managed democracy, the “surface democracy”.

Surface democracies are wildly, raucously competitive. Two or more parties wage an all-out cinematic slugfest over hot-button issues with big, beautiful ratings. There may be a kaleidoscopic cast of quixotic minor parties with unusual obsessions filling the role of comic relief, usually only lasting for a season or two of the hit show Democracy. The spectacle is gripping, everybody is awed by how high the stakes are and agonizes over how to cast their precious vote. Meanwhile, in a bland gray building far away from the action, all of the real decisions are being made by some entirely separate organ of government that rolls onwards largely unaffected by the show.

Tikka T3x Arctic / Canadian Rangers C19 Rifle, 7.62 / .308 Win

Bloke on the Range

Published 29 Mar 2019Bloke unboxes and takes a first look at the Tikka T3x Arctic rifle, adopted as the C19 rifle for the Canadian Rangers in 7.62 NATO / .308 Winchester. Is the hype real? Oh yes! Yes, it really is!

(more…)

QotD: The general’s pre-battle speech to the army

The modern pre-battle general’s speech is quite old. We can actually be very specific: it originates in a specific work: Thucydides’ Histories [of the Peloponnesian War] (written c. 400 B.C.). Prior to this, looking at Homer or Herodotus, commanders give very brief remarks to their troops before a fight, but the fully developed form of the speech, often presented in pairs (one for each army) contrasting the two sides, is all Thucydides. It’s fairly clear that a few of Thucydides’ speeches seem to have gone on to define the standard form and ancient authors after Thucydides functionally mix and match their components (we’ll talk about them in a moment). This is not a particularly creative genre.

Now, there is tremendous debate as to if these speeches were ever delivered and if so, how they were delivered (see the bibliography note below; none of this is really original to me). For my part, while I think we need to be alive to the fact that what we see in our textual sources are dressed up literary compressions of the tradition of the pre-battle speech, I suspect that, particularly by the Roman period, yes, such speeches were a part of the standard practice of generalship. Onasander, writing about the duties of a general in the first century CE, tells us as much, writing, “For if a general is drawing up his men before battle, the encouragement of his words makes them despise the danger and covet the honour; and a trumpet-call resounding in the ears does not so effectively awaken the soul to the conflict of battle as a speech that urges to strenuous valour rouses the martial spirit to confront danger.” Onasander is a philosopher, not a military man, but his work became a standard handbook for military leaders in Antiquity; one assumes he is not entirely baseless.

And of course, we have the body of literature that records these speeches. They must be, in many cases, invented or polished versions; in many cases the author would have no way of knowing the real worlds actually said. And many of them are quite obviously too long and complex for the situations into which they are placed. And yet I think they probably do represent some of what was often said; in many cases there are good indications that they may reflect the general sentiments expressed at a given point. Crucially, pre-battle speeches, alone among the standard kinds of rhetoric, refuse to follow the standard formulas of Greek and Roman rhetoric. There is generally no exordium (meaning introduction; except if there is an apology for the lack of one, in the form of, “I have no need to tell you …”) or narratio (the narrated account), no clear divisio (the division of the argument, an outline in speech form) and so on. Greek and Roman oratory was, by the first century or so, quite well developed and relatively formulaic, even rigid, in structure. The temptation to adapt these speeches, when committing them to a written history, to the forms of every other kind of oratory must have been intense, and yet they remain clearly distinct. It is certainly not because the genre of the battle speech was more interesting in a literary sense than other forms of rhetoric, because oh my it wasn’t. The most logical explanation to me has always been that they continue to remain distinct because however artificial the versions of battle speeches we get in literature are, they are tethered to the “real thing” in fundamental ways.

Finally, the mere existence of the genre. As I’ve noted elsewhere, we want to keep in mind that Greek and Roman literature were produced in extremely militarized societies, especially during the Roman Republic. And unlike many modern societies, where military service is more common among poorer citizens, in these societies military service was the pride of the elite, meaning that the literate were more likely both to know what a battle actually looked like and to have their expectations shaped by war literature than the commons. And that second point is forceful; even if battle speeches were not standard before Thucydides, it is hard to see how generals in the centuries after him could resist giving them once they became a standard trope of “what good generals do.”

So did generals give speeches? Yes, probably. Among other reasons we can be sure is that our sources criticize generals who fail to give speeches. Did they give these speeches? No, probably not; Plutarch says as much (Mor. 803b) though I will caution that Plutarch is not always the best when it comes to the reality of the battlefield (unlike many other ancient authors, Plutarch was a life-long civilian in a decidedly demilitarized province – Achaea – who also often wrote at great chronological distance from his subjects; his sense of military matters is generally weak compared to Thucydides, Polybius or Caesar, for instance). Probably the actual speeches were a bit more roughly cut and more compartmentalized; a set of quick remarks that might be delivered to one unit after another as the general rode along the line before a battle (e.g. Thuc. 4.96.1). There are also all sorts of technical considerations: how do you give a speech to so many people, and so on (and before you all rush to the comments to give me an explanation of how you think it was done, please read the works cited below, I promise you someone has thought of it, noted every time it is mentioned or implied in the sources and tested its feasibility already; exhaustive does not begin to describe the scholarship on oratory and crowd size), which we’ll never have perfect answers for. But they did give them and they did seem to think they were important.

Why does that matter for us? Because those very same classical texts formed the foundation for officer training and culture in much of Europe until relatively recently. Learning to read Greek and Latin by marinating in these specific texts was a standard part of schooling and intellectual development for elite men in early modern and modern Europe (and the United States) through the Second World War. Napoleon famously advised his officers to study Caesar, Hannibal and Alexander the Great (along with Frederick II and the best general you’ve never heard of, Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden). Reading the classical accounts of these battles (or, in some cases, modern adaptations of them) was a standard part of elite schooling as well as officer training. Any student that did so was bound to run into these speeches, their formulas quite different from other forms of rhetoric but no less rigid (borrowing from a handful of exemplars in Thucydides) and imbibe the view of generalship they contained. Consequently, later European commanders tended for quite some time to replicate these tropes.

(Bibliography notes: There is a ton written on ancient battle speeches, nearly all of it in journal articles that are difficult to acquire for the general public, and much of it not in English. I think the best possible place to begin (in English) is J.E. Lendon, “Battle Description in the Ancient Historians Part II: Speeches, Results and Sea Battles” Greece & Rome 64.1 (2017). The other standard article on the topic is E. Anson “The General’s Pre-Battle Exohortation in Graeco-Roman Warfare” Greece & Rome 57.2 (2010). In terms of structure, note J.C. Iglesias Zoida, “The Battle Exhortation in Ancient Rhetoric” Rhetorica 25 (2007). For those with wider language skills, those articles can point you to the non-English scholarship. They can also serve as compendia of nearly all of the ancient battle speeches; there is little substitute for simply reading a bunch of them on your own.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Battle of Helm’s Deep, Part VII: Hanging by a Thread”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-06-12.

April 5, 2023

The modern Canadian Army – go on deployment to Poland, train Ukraine troops … and have to buy your own rations

Is it hard to figure out why the Canadian Armed Forces are having recruiting shortfalls when they can’t even manage to feed the troops they send overseas to train Ukrainian soldiers?

Operation Unifier shoulder patch for Canadian troops in Ukraine.

Detail from a photo in the Operation Unifier image gallery – https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/operations/military-operations/current-operations/operation-unifier.html

The Canadian soldiers are in Poland to train Ukrainian military personnel but since Canada did not send military cooks on the mission, the troops were told to eat at local restaurants.

But there is a massive backlog with the Canadian Forces reimbursing the soldiers for those costs, sending some of them thousands of dollars into debt. Their families contacted this newspaper to complain about the situation they say is causing financial stress at home.

After this newspaper [the Ottawa Citizen] inquired about the situation, the Canadian Forces confirmed Monday that there are problems with payments of per diems and the reimbursement of other expenses. The Canadian Forces is now promising to speed up the process.

“We apologize to the members and their families for the distress this has caused, and thank them for their patience,” said Capt. Nicolas Plourde-Fleury, spokesman for Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC). “We want them to know we have implemented measures to better support them moving forward.”

Approximately 100 Canadian military personnel are currently serving in Poland as part of a contingent to train Ukraine troops. The first arrived in October 2022 but the mission added more personnel in February and March.

As part of Operation Unifier, the Canadian soldiers are providing training in basic and advanced engineering skills, the use of explosives for demolition work, demining and skills relating to the use and operation of the Leopard 2 tanks in combat.

The Canadian Forces usually has its own cooks to provide troops with food. But in this situation, the Canadians initially received their meals from the Polish military. Later, the Canadian soldiers were told to eat in local restaurants and they would be reimbursed by the Canadian Forces.

The fate of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police after the Mass Casualty Commission report

In her new Substack, Tasha Kheiriddin considers what should be done with the RCMP in the wake of the Mass Casualty Commision’s report on, among other things, the cultural and structural problems within the force that contributed to the death toll in Portapique:

The first thing the federal government should do is break up the RCMP. It should give local policing contracts to provincial and regional police and focus a new national force solely on national policing.

Former RCMP officer Garry Clement, author of the forthcoming book Under Cover: Inside the Shady World of Organized Crime and the RCMP, gives a blunt assessment of the situation. In an email to In My Opinion, he stated that “The RCMP has two choices: 1) relinquish contracts and focus on their federal mandates; or 2) maintain contracts but create a ‘Firewall’ between both areas and enable the federal side to have permanent resources in their wheelhouse with their own metrics for salaries.”

Considering how the force is currently structured, a financial firewall won’t be enough to ensure adequate delivery of both mandates. It is unreasonable to expect a national force to deliver community policing at the standards expected in the 21st century. Vice versa, it is also unreasonable for officers who cut their teeth in remote communities to go on to tackle big city, national and international criminal matters.

One of the main recommendations of the Mass Casualty Report is that the federal public safety minister commission an independent review of the RCMP and examine the force’s approach to contract policing. But some believe they should act now, and leave local policing to local police.

Todd Hataley is a professor in the School of Justice and Community Development at Fleming College and a retired member of the RCMP, where he worked as an investigator in organized crime, national security, cross-border crime and extra-territorial torture. He offered these thoughts on a Teams call the day after the report came out.

The RCMP is currently structured with a paramilitary, top-down approach, making it difficult to retrain middle management. It is a paramilitary structure that doesn’t work for modern policing, where you need partnerships for mental health, where you need to get ahead of problems.

Local policing needs to be responsive to local demands,” continued Hataley. This is particularly true of indigenous communities. “There’s a good body of research that shows that indigenous officers use less force, about one tenth that of non-indigenous officers. In my experience, service is better when less force is used. There are better relations with the community.”

Some communities have already cut ties due to this lack of community engagement. Last December the town council of Surrey, BC, ended its contract with the RCMP, even though it will cost more to hire local police. It cited the growth of a large South Asian community in the area and the fact that the RCMP’s structure did not facilitate development of an adequate relationship.

Interviewed in the Toronto Star about this issue earlier this year, Curt Griffiths, a criminology professor at Simon Fraser University in B.C., echoed that assessment. “RCMP officers — and it’s not their fault; it’s the way the system’s set up — they’re just passing through,” he said. “There’s a cost to that in terms of community policing, community engagement, knowledge of the community.”

Similarly, in March of 2023 the Alberta community of Grande Prairie voted to create a municipal police service. Councilor Gladys Blackmore told CTV News that training issues were one of the reasons. “I’m frustrated by the fact that 40 out of our 97 officers have come directly to us from Depot, and that means they are inexperienced, and they still require a significant amount of training, which the RCMP chooses to send them away for.”

Justin Trudeau chooses the Argentinian model over the Canadian model

In The Line, Matt Gurney considers the proposition that “Canada is broken”:

To the growing list of articles grappling with the issue of whether Canada is broken — and how it’s broken, if it is — we can add this one, by the Globe and Mail‘s Tony Keller. I can say with all sincerity that Keller’s is one of the better, more thoughtful examples in this expanding ouevre. Keller takes the issue seriously, which is more than can be said of some Canadian thought leaders, whose response to the question is often akin to the Bruce Ismay character from Titanic after being told the ship is doomed.

(Spoiler: it sank.)

But back to the Globe article. Specifically, Keller writes about how once upon a time, just over a century ago, Canada and Argentina seemed to be on about the same trajectory toward prosperity and stability. If anything, Argentina may have had the edge. Those with much grasp of 20th-century history will recall that that isn’t exactly how things panned out. I hope readers will indulge me a long quote from Keller’s piece, which summarizes the key points:

By the last third of the 20th century, [Argentina] had performed a rare feat: it had gone backward, from one of the most developed countries to what the International Monetary Fund now classifies as a developing country. Argentina’s economic output is today far below Canada’s, and consequently the average Argentinian’s income is far below that of the average Canadian.

Argentina was not flattened by a meteor or depopulated by a plague. It was not ground into rubble by warring armies. What happened to Argentina were bad choices, bad policies and bad government.

It made no difference that these were often politically popular. If anything, it made things worse since the bad decisions – from protectionism to resources wasted on misguided industrial policies to meddling in markets to control prices – were all the more difficult to unwind. Over time the mistakes added up, or rather subtracted down. It was like compound interest in reverse.

And this, Keller warns, might be Canada’s future. As for the claim made by Pierre Poilievre that “Canada is broken”, Keller says this: “It’s not quite right, but it isn’t entirely wrong.”

I disagree with Keller on that, but I suspect that’s because we define “broken” differently. We at The Line have tried to make this point before, and it’s worth repeating here: we think a lot of the pushback against the suggestion that Canada might be broken is because Canada is still prosperous, comfy, generally safe, and all the rest. Many, old enough to live in paid-off homes that are suddenly worth a fortune, may be enjoying the best years of their lives, at least financially speaking. Suggesting that this is “broken” sometimes seems absurd.

But it’s not: it’s possible we are broken but enjoying a lag period, spared from feeling the full effects of the breakdown by our accumulated wealth and social capital. The engines have stopped, so to speak, but we still have enough momentum to keep sailing for a bit. Put more bluntly, “broken” isn’t a synonym for “destroyed”. A country can still be prosperous and stable and also be broken — especially if it was prosperous and stable for long enough before it broke. The question then becomes how long the prosperity and stability will last. Canada is probably rich enough to get away with being broken for a good long while. What’s already in the pantry will keep us fed and happy for years to come.

But not indefinitely.

PTRS 41: The Soviet Semiauto Antitank Rifle (aka an SKS on Steroids)

Forgotten Weapons

Published 14 Dec 2022Prior to World War Two, the Soviet Union had a rather lackluster interest in antitank rifles — a series of guns were developed, but slowly and without all that much success. The Barbarossa invasion gave a very immediate need for just this sort of weapon, however, to give Soviet infantry units an organic anti-armor capability. Two star Soviet designers were tasked with designing AT rifles, Degtyarev and Simonov. The cartridge they were to use was the new 14.5x114mm, a high-velocity monster using a tungsten carbine cored projectile.

After a shockingly fast development period, the guns from both design bureaus were accepted. The Degtyarev became the PTRD-41, a single-shot auto-ejecting design that was extremely cheap and fast to produce. The Simonov design became the PTRS-41, a 5-shot semiauto offering more firepower but also taking longer to produce. The Degtyarev entered service first, with the first substantial deliveries of PTRS rifles arriving in 1942.

Both designs would serve through the war, with hundreds of thousands being made. Many were put into storage in 1945, and they are still seen today in Ukraine periodically. The PTRS would go on to be the basis for Simonov’s 7.62x39mm infantry rifle, adopted as the SKS.

(more…)

QotD: Harry Flashman’s adventures were not intended as “covert anticolonialism”

In their insistence on judging the value of a work of art principally in terms of its moral qualities, the publishers of today are heirs to a tradition of puritanism going back to Plato. But there has long been an anti-puritanical argument available too, the most notorious of them being the one articulated by Oscar Wilde: that to assess art in moral terms is to commit some sort of category mistake. “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well-written, or badly written. That is all.” But that argument was never very persuasive by itself, and contains a large non sequitur. Why should that be “all”? Why can’t it be that part of what we’re saying in calling a book well-written is that it is morally exemplary? Surely it is those who call on us to leave our moral values at the door who have some explaining to do.

George MacDonald Fraser himself sometimes seemed to take Wilde’s view of the matter. He zealously repudiated, in his non-fiction, all attempts to defend his fiction as covertly anti-colonial, taking great pleasure in mocking critics who “hailed it as a scathing attack on British imperialism”. Was he “taking revenge on the 19th century on behalf of the 20th”? “Waging war on Victorian hypocrisy”? Were the books, as one religious journal was supposed to have claimed, “the work of a sensitive moralist” highly relevant to “the study of ethics”? No, he said, The Flashman Papers were to be taken “at face value, as an adventure story dressed up as the memoirs of an unrepentant old cad”.

Is Fraser’s avowed amoralism the whole story? In one respect, the Flashman books are certainly amoral: they embody no systematic view that colonialism was wrong, illegitimate, unjust. (Nor, come to it, do they embody the view that it was right, legitimate and just.) As Fraser appears to see it in his fiction, empire was simply the default mode of political life in much of the world. This indeed was the case for much of human history. To be colonised was generally a misfortune for the colonised, but the individual coloniser was neither hero nor villain, just a self-interested actor acting on what he believed to be the necessities of his time and place.

We live in a world where we are constantly exercised by the problem of complicity. We wonder: am I complicit in climate change because I just put on the washing machine? In a sufficiently inclusive sense of the word “complicit”, of course I am: one of countless agents whose everyday actions add a tiny bit more carbon to the atmosphere. But outside an ethics seminar, what I’d tell you is that I was just doing my laundry because the clothes were beginning to stink.

Fraser was a deft enough writer to force his characters to confront the larger, what we today might call “structural” questions, in terms that belong to their own times, not to ours. At a pivotal moment in Flash for Freedom, Flashman is enslaved himself in America. Thrown into a cart with a charismatic slave called Cassy, he gets to hear her relish the irony of his position: “Well, now one of you knows what it feels like … Now you know what a filthy race you belong to.” Is there any hope of escape, he asks her desperately. None, she replies, “there isn’t any hope. Where can you run to, in this vile country? This land of freedom! With slave-catchers everywhere, and dogs, and whipping-houses, and laws that say I’m no better than a beast in a sty!” Flashman has the grace to be silent; what can he say?

Nikhil Krishnan, “Harry Flashman’s imperial morality”, UnHerd, 2022-12-26.

April 4, 2023

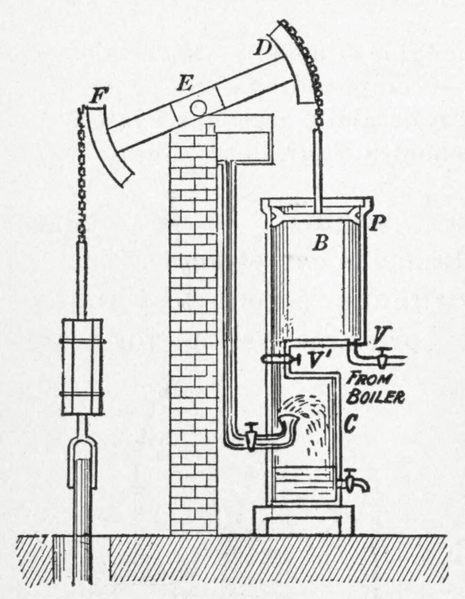

When the steam engine itself was an “intangible”

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes explains why the steam engine patent of James Watt didn’t immediately lead to Watt and his partner Matthew Boulton building a factory to create physical engines:

Diagram of a Watt steam engine from Practical physics for secondary schools (1913).

Wikimedia Commons.

… one of the most famous business partnerships of the British Industrial Revolution — that between Matthew Boulton and James Watt from 1775 — was originally almost entirely based on intangibles.

That probably sounds surprising. James Watt — a Scottish scientific instrument-maker, chemist and civil engineer — became most famous for his improvements to the steam engine, an almost archetypal example of physical capital. In the late 1760s he radically improved the fuel efficiency of the older Newcomen engine, and then developed ways to regulate the motions of its piston — traditionally applied only to pumping water — so that it could be suitable for directly driving machinery (I’ll write more on the invention itself soon). His partnership with Matthew Boulton, a Birmingham manufacturer of buttons, candlesticks, metal buckles and the like — then called “toys” — was also based from a large, physical site full of specialised machinery: the Soho Manufactory. On the face of it, these machines and factories all sound very traditionally tangible.

But the Soho Manufactory was largely devoted to Boulton’s other, older, and ongoing businesses, and it was only much later — over twenty years after Boulton and Watt formally became partners — that they established the Soho Foundry to manufacture the improved engines themselves. The establishment of the Soho Foundry heralded James Watt’s effective retirement, with the management of this more tangible concern largely passing to his and Boulton’s sons. And when Watt retired formally, in 1800, this coincided with the full depreciation of the intangible asset upon which he and Boulton had built their business: his patent.

Watt had first patented his improvements to the steam engine in 1769, giving him a 14-year window in which to exploit them without any legal competition. But his financial backer, John Roebuck, who had a two-thirds share in the patent, was bankrupted by his other business interests and struggled to support the engine’s development. Watt thus spent the first few years of his patent monopoly as a consultant on various civil engineering projects — canals, docks, harbours, and town water supplies — in order to make ends meet. The situation gave him little time, capital, or opportunity to exploit his steam engine patent until Roebuck was eventually persuaded to sell his two-thirds share to Matthew Boulton. With just eight years left on the patent, and having already wasted six, Boulton and Watt lobbied Parliament to grant them an extension that would allow them to bring their improvements into full use. In 1775 Watt’s patent was extended by Parliament for a further twenty-five years, to last until 1800. It was upon this unusually extended patent that they then built their unusually and explicitly intangible business.

How was it intangible? As Boulton and Watt put it themselves, “we only sell the licence for erecting our engines, and the purchaser of such licence erects his engine at his own expence”. This was their standard response to potential customers asking how much they would charge for an engine with a piston cylinder of particular dimensions. The answer was, essentially, that they didn’t actually sell physical steam engines at all, so there was no way of estimating a comparable figure. Instead, they sold licences to the improvements on a case-by-case basis — “we make an agreement for each engine distinctly” — by first working out how much fuel a standard, old-style Newcomen engine would require when put to use in that place and context, and then charging only a third of the saving in fuel that Watt’s improvements would provide. “The sum therefore to be paid during the working of any engine is not to be determined by the diameter of the cylinder, but by the quantity of coals saved and by the price of coals at the place where the engine is erected.” They fitted the licensed engines with meters to see how many times they had been used, sending agents to read the meters and collect their royalties every month or year, depending on the location.

This method of charging worked well for refitting existing Newcomen engines with Watt’s improvements — in those cases the savings would be obvious. It also meant that Boulton and Watt incentivised themselves to expand the total market for steam engines. The older Newcomen engines were mainly used for pumping water out of coal mines, where the coal to run them was at its cheapest. It was one of the few places where Newcomen engines were cost-effective. But for Watt and Boulton it was at the places where coals were most expensive, and where their improvements could thus make the largest fuel savings, that they could charge the highest royalties. As Boulton wrote to Watt in 1776, the licensing of an engine for the coal mine of one Sir Archibald Hope “will not be worth your attention as his coals are so very cheap”. It was instead at the copper and tin mines of Cornwall, where coal was often expensive, having to be transported from Wales, that the royalties would be the most profitable. As Watt put it to an old mentor of his in 1778, “our affairs in other parts of England go on very well but no part can or will pay us so well as Cornwall”.

History Summarized: the Ancient Greek Post-Apocalypse

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 31 Mar 2023Turns out the “Studio Ghibli Post-Apocalypse” aesthetic has a historical basis in ancient Greek history’s Bronze Age Collapse, long Dark Age, and slow re-emergence into the Polis Age. I don’t know if I’d call the process pleasant, but it sure as hell is a vibe.

GO READ THE ILIAD: https://bookshop.org/p/books/the-ilia… — We enjoy the Fagles translation, as it’s the typical classroom and library standard, but if you want a real treat, try the Alexander Pope edition from the 1700s that’s written entirely in RHYME. THE DAMN THING RHYMES!!!

SOURCES & Further Reading:

“The Age of Heroes” and “Delphi and Olympia” from Ancient Greek Civilization by Jeremy McInerney – “Dark Age and Archaic Greece” from The Foundations of Western Civilization by Thomas F. X. Noble – “Dark Age and Archaic Greece” from The Greek World: A Study of History and Culture by Robert Garland “The Greeks: A Global History” by Roderick Beaton, “The Greeks: An Illustrated History” by Diane Cline, Metropolitan Museum “Geometric Art in Ancient Greece” https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grg… also have a degree in Classical Studies

(more…)