Science fiction and fantasy are the only genres in which a series can be defined by the universe in which it is set, which, when you think about it, gives a vast lot of creative elbow-room, potentially.

Lois McMaster Bujold, interview at Blogcritics, 2005-05-24.

November 16, 2021

QotD: Writing SF and fantasy

November 13, 2021

The patron saint of “Gonzo” journalism was a pretty cruddy human being

As I mentioned in an earlier post on one of Hunter S. Thompson’s famous early books, I discovered the writer at a particularly susceptible age … teenagers of my generation were generally suckers for counter-culture heroes (being too young to be actual hippies because we were in primary school when the Summer of Love flew past, and therefore feeling we’d missed out on something Big and Important and Meaningful). As a gullible teen, I believed Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was mostly factual with some obvious-even-to-me embroideries for dramatic or comedic effect. I could easily forgive the guessed-at 10% fiction, but Thompson eventually admitted that the majority of the story was bullshit. Entertaining bullshit, but bullshit.

Which, as it happens, turns out to have been Thompson’s life-long modus operandi, as Kevin Mims repeatedly highlights in his Quillette review of David S. Wills’ biography called High White Notes: The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism:

In High White Notes, his riveting new biography of Hunter S. Thompson, journalist David S. Wills describes Thompson as America’s first rock star reporter and compares him to Mick Jagger. But by the time I finished the book, I’d decided that Thompson bore a closer resemblance to Donald Trump. The two men were born nine years apart, during white American masculinity’s golden age. Both were obsessed with politics without possessing anything that could be described as a coherent political philosophy. Both men longed for some mythical American paradise of the past. Both men screwed over multiple friends and business partners. Both men would have gone broke if not for the frequent intervention of helpful patrons. Both men were egomaniacs fond of self-mythologizing and loath to share a spotlight with anyone. Both men enjoyed making disparaging remarks about women, minorities, the disabled, and other disadvantaged people. Both men were frequently disloyal to their most loyal aiders and abetters. Thompson’s endless letter writing and self-pitying 3am telephone calls to friends and colleagues were the 20th century equivalent of Trump’s late-night Twitter tantrums. Both men generally exaggerated their successes and blamed their failures on others. Both men mistreated their wives. Both men nursed a constant (and not entirely irrational) sense of grievance against perceived enemies in the government and the media. Both men had a colossal sense of entitlement …

The list could go on and on. Trump actually fares better than Thompson by various measures. For instance, Trump has never had a drug or alcohol problem, as far as I know. Thompson was a drug and alcohol problem. The first US president in living memory without a White House pet seems to have no interest in animals. Thompson enjoyed tormenting them. Rumors have circulated since 2015 that a recording exists of Trump using a racial slur but since the evidence has never surfaced, it might be fairer to conclude (at least provisionally) that this is not one of his many character failings. Thompson’s published and (especially) unpublished writings are full of such language.

All of which may lead you to conclude that High White Notes is not a favorable account of Hunter S. Thompson’s life and work. To the contrary, David S. Wills is a Thompson devotee who considers his subject to have been a great writer and, at times, a great journalist. But Wills is an honest guide, so his endlessly entertaining biography manages to be both a fan’s celebration and unsparing in its criticism of Thompson and his work.

Though impressive, the book is not without faults. Wills relies too heavily on cliché (“This book will pull no punches”; “breathing down his neck for the final manuscript”; “women threw themselves at him” etc.), and has a tendency to find profundity in unnaturally strained readings of Thompson’s prose. For instance, Wills describes a scene from a 1970 profile Thompson wrote of French skier Jean-Claude Killy, in which three young boys approach Thompson and ask if he is Killy. Thompson tells them that he is, then holds up his pipe and says, “I’m just sitting here smoking marijuana. This is what makes me ski so fast.” This sounds to me like standard Thompson misbehavior, but Wills infers something more complex: “On the surface, it appears to be comedy for the sake of comedy but in fact it is a comment on the nature of celebrity and in particular Killy’s empty figurehead status.” And when Thompson describes Killy as resembling “a teenage bank clerk with a foolproof embezzlement scheme,” Wills remarks, “Thompson has succeeded mightily not just in conveying [Killy’s] appearance but in hinting at his personality. He has placed an image in the head of his reader that will stick there permanently. It was something F. Scott Fitzgerald achieved, albeit in more words, when he had Nick Carraway describe Jay Gatsby’s smile.” (The book, by the way, takes its title from Fitzgerald, who used the phrase to describe short passages of writing so beautiful that they stand out from the larger work of which they are a part.)

[…]

Thompson’s big break as a writer came in 1965 when he was hired to write an article about the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang for the Nation. The piece was so popular that Thompson found himself besieged by publishers who wanted him to expand it into a full-length nonfiction book. The Thompsons moved into the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco and Thompson set about writing Hell’s Angels, the 1967 book that would make him famous. Even in that first book, written before he had fully formulated the concept of Gonzo journalism, Thompson was already tinkering with the truth and engaging in the kind of self-mythologizing that would become a hallmark of his work. And that didn’t sit well with the Hell’s Angels themselves. According to Sonny Barger, a founding member of the Angels, Thompson “would talk himself up that he was a tough guy, when he wasn’t. When anything happened, he would run and hide.” Barger’s assessment of the book was terse: “It was junk.”

Wills notes that Thompson “tended to write about himself in ways that built his legend … to prove his machismo on paper. The back cover [of Hell’s Angels] describes him as ‘America’s most brazen and ballsy journalist’ and in the book he tells the story of first meeting the Angels and trying to impress them by shooting out the windows of his own San Francisco home. Such moments of bravado tend to enter the story very briefly and seem to serve little purpose beyond this self-mythologizing.”

But it was exactly this kind of self-mythologizing — the bragging about his drug use and general misbehavior — that editors of American magazines found so exciting about Thompson’s work, so it’s no wonder that he engaged in so much of it. It was his wild man persona that made Warren Hinckle of Scanlan’s Monthly want to unleash him among the socialites of Louisville. Still, Thompson didn’t fully emerge as a countercultural hero until he began to write for a small start-up publication in San Francisco called Rolling Stone.

November 7, 2021

Apparently we need to block the “Random Penguin & Schuster” merger to protect the 0.001%

In the most recent SHuSH newsletter from Kenneth Whyte, the US Department of Justice case against allowing the proposed merger of Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster is examined in some detail:

On Tuesday, the US Justice Department (DOJ) filed suit to block Penguin Random House from purchasing its rival, Simon & Schuster, for $2.18 billion. It promises to be a fascinating case, in part because there’s so much at stake for the two firms involved, and also because of the unusual angle from which the DOJ is attacking the file.

As one of two US agencies responsible for enforcing antitrust law (the other is the Federal Trade Commission), the DOJ believes the proposed deal, struck last year, would leave Penguin Random House, already the world’s largest publisher of consumer books, “towering over its rivals”. The combined entity would have revenues more than twice its next closest competitor, and “outsized influence over who and what is published, and how much authors are paid for their work”.

Bertelsmann, owner of Penguin Random House, and Viacom, owner of Simon & Schuster, promise to fight the DOJ in court. They acknowledge that the Big Five Publishers, a grouping that also includes Hachette, HarperCollins, and Macmillan, will be a Big Four after the merger, but maintain that these firms plus new publishing entrants, such as Amazon, and an abundance of small and midsize publishers will provide sufficient competition for authors and books. “The publishing industry is, and following this transaction will remain, a vibrant and highly competitive environment,” they said in a joint statement.

So far, so ordinary corporate behaviour. Who or what do we need to protect, beyond hoping to maintain something vaguely resembling a competitive marketplace for books? A tiny sub-set of authors:

With this suit, the DOJ is taking a narrower approach. One test of whether a merger results in illegal market dominance is spelled out in the Horizontal Merger Guidelines jointly issued by the DOJ and the FTC: it asks if the combined firm would be in a position to increase its profits by imposing a price cut — a small but significant and lasting price cut — on one of its suppliers. In other words, if the new and enlarged Penguin Random House is better able than the old Penguin Random House to squeeze one supplier on one product line, the merger is illegal.

To apply this test to the deal, the DOJ needs to identify which supplier and which product line is vulnerable if the firms are allowed to merge. It has a range of options. Book publishing is a complicated marketplace, with many suppliers and product lines. Publishers sell books to retailers, and market books to consumers; they buy distribution services, printing, advertising, editorial services, and so on. The DOJ might have argued that a merged Penguin Random House-Simon & Schuster would have the muscle to make its printers or copyeditors reduce their rates. Or that it could force retailers to accept smaller cuts of sales revenue.

Instead, the DOJ put its chips on the discreet line of business in which authors supply manuscripts to publishing houses. Its complaint says that the combined firm would have the power to improve its profits by significantly and permanently lowering the advances it pays to authors for the rights to publish their books.

Advances, notes the DOJ, provide the bulk of author income at the Big Five publishing houses (few authors earn out their advances and collect further royalties). Were Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster to combine, there would be nothing to deter it “from imposing a small, but significant, and non-transitory decrease in advances”. And if it did so, the complaint maintains, authors would have nowhere to turn. The DOJ ignores the existence of the other three members of the Big Five. It admits that the US has 3,000 small and mid-size houses but, these, according to the complaint, are economically irrelevant, mere “farm teams” for the big houses. Self-publishing, it adds, is not a serious alternative.

That may sound like the DOJ is suing to stop this merger on behalf of the writing community, a heartwarming notion, but it’s not. The lawsuit is primarily concerned with a small subset of writers: those who produce “anticipated top-selling books”. According to the complaint, there exists a small but definable market for “anticipated top-selling books”. It represents a distinct line of commerce, as required under the Clayton Act, and that is the real focus of the complaint.

The DOJ is going to war for sellers of “anticipated top-selling books”, the .001% of the publishing world.

Its lawyers foresee a time when Penguin Random House-Simon & Schuster will target John Grisham and his ilk with lower advances, and John Grisham will have no choice but to accept. So far as the DOJ is concerned, that is how this merger fails the Horizontal Merger Guidelines, and why it is illegal. The phrase “anticipated top-selling books” appears 29 times in a 26-page document.

October 26, 2021

QotD: Blogging

That’s the big problem with blogs, of course: who cares what X thinks? It all depends on the quality of the thought, the uniqueness of the product, the value added. In the blogworld, a celebrity name adds no value whatsoever. If the blog’s good, the celebrity may earn some blogcred (oh, Lord, shoot me now for that one) for not sounding like someone who just emerged from the isolation tank of LA culture. But I really don’t care what Larry David thinks about John Bolton. I care what Larry David thinks about the itchy tags on shirts that scrape your neck, because I know that he can make a 12-part TV series that revolves around that detail, and George Will can’t.

We’ll see. In a way blogs are the refutation of the old joke: “The food’s so bad here.” “Yes, and such small portions.” Dole out crap in large amounts all day and you don’t guarantee traffic; eventually people will tired of poking through the heap with a stick looking for diamonds.

Somewhere in there, there’s a metaphor.

James Lileks, The Bleat, 2005-05-10.

October 1, 2021

September 12, 2021

Terry Pratchett: Discworld And Beyond

September 7, 2021

QotD: Calvin was right

Calvin: “I used to hate writing assignments, but now I enjoy them. I realized that the purpose of writing is to inflate weak ideas, obscure poor reasoning, and inhibit clarity. With a little practice, writing can be an intimidating and impenetrable fog! Want to see my book report?”

Hobbes: “‘The Dynamics of Interbeing and Monological Imperatives in Dick and Jane: A Study In Psychic Transrelational Gender Modes.'”

Calvin: “Academia, here I come!”

Bill Watterson, Calvin and Hobbes.

September 3, 2021

QotD: Drama critics

There is one thing that 99 percent of all critics share with one another: they are failures. I don’t mean failures as critics — my God, that’s understood. I don’t even mean they are failures as people; I mean something more painful by far: These people are failures in life.

It’s a second-rate job, folks. Being a drama critic on Broadway wouldn’t keep a decent mind occupied 10% of the time. So you don’t even get second-raters. You get the dregs, the stage-struck but untalented neurotic who eventually drifts into criticism as a means of clinging peripherally to the arts. And most of your cruel critics come this way: they are getting their own back.

William Goldman, The Season: A Candid Look at Broadway, 1969.

August 1, 2021

July 19, 2021

July 9, 2021

Alexander Larman on George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman novels

I happened upon a copy of the first Flashman in my teens and was totally taken in by the assertion that the book was about “a real historical figure involved in most of the Victorian era’s most notorious episodes and that his papers were discovered during a sale of household furniture at Ashby, Leicestershire in 1965.” I’d watched the TV adaptation of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, so I had some awareness about the character Flashman, which only helped keep the cover story going for me. I absolutely loved the book and while it eventually became clear that it was fiction, I haunted the bookshops for years afterwards searching for more from Fraser. In The Critic, Alexander Larman looks at the author and his works — which almost certainly could never have been published in this neo-Victorian age:

When Flashy first entered the scene in bestselling form in 1969, there was confusion as to whether the tales were fanciful fiction or eyebrow-raising fact. This was due to MacDonald Fraser’s straight-faced claim that his protagonist was a real historical figure involved in most of the Victorian era’s most notorious episodes and that his papers were discovered during a sale of household furniture at Ashby, Leicestershire in 1965.

MacDonald Fraser presented himself as an impartial editor. He wrote, “I have no reason to doubt that it is a completely truthful account; where Flashman touches on historical fact he is almost invariably accurate, and readers can judge whether he is to be believed or not on more personal matters.”

The subterfuge succeeded. A third of the initial reviews treated it as a serious work of non-fiction, rather than a brilliantly conceived and superbly written counter-factual piece.

Not bad for the continued exploits of a minor character in the sanctimonious Victorian novel Tom Brown’s Schooldays, whose major achievement is to bully the protagonist and his friend Harry “Scud” East, before being expelled for drunkenness. It set its creator on a hugely lucrative path, and established him as one of the great comic novelists of his day.

MacDonald Fraser was a contradictory figure. A patriotic right-winger who had a deep respect for other cultures and peoples; one of Hollywood’s most in-demand screenwriters who happily lived on the Isle of Man in a self-conscious recreation of “the good old days”; a fully paid-up reactionary who wished to reintroduce corporal and capital punishment, but who loathed British incursions abroad.

Above all, he despised cant and hypocrisy. He described Tony Blair as “not just the worst prime minister we’ve ever had, but by far the worst prime minister we’ve ever had” and angrily added, “it makes my blood boil to think of the British soldiers who’ve died for that little liar.”

Christopher Hitchens, who may not have agreed with his views on foreign expeditions, but knew a thing or two about the value of being able to hold one’s drink, was a friend of MacDonald Fraser’s. When Hitchens telephoned him on his eightieth birthday to offer his regards, he was stoutly informed that he shared the company of “Charlemagne, Casanova, Hans Christian Andersen and Kenneth Tynan” on that date.

Their politics may have differed — Christopher acknowledged MacDonald Fraser’s “robust Toryism” — but Hitchens respected the older writer’s enduring affection for his Zulu, Sikh and Afghan characters, as well as the dutiful admiration he showed towards both American culture and its presidents.

June 6, 2021

George Orwell’s “Politics And The English Language” remains the best guide to writing non-fiction

Despite pulling most of his writing behind a paywall, I still get the occasional “Weekly Dish” post excerpt from Andrew Sullivan, including his homage to the still-relevant Orwell essay “Politics and the English Language”:

From time to time, I make sure to re-read George Orwell’s classic essay, “Politics And The English Language“. It remains the best guide to writing non-fiction, and it usually prompts a wave of self-loathing even more piercing than my habitual kind. What it shows so brilliantly is how language itself is central to politics, that clarity is as hard as it is vital, and that blather is as lazy as it is dangerous. It’s dangerous because the relationship between our words and our politics goes both ways: “[The English language] becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts”. We create language and language creates us. If the language is corrupted, so are we.

Near the end of the essay, Orwell lists a few rules to keep writing clear, accessible and meaningful:

i. Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

ii. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

iii. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

iv. Never use the passive where you can use the active.

v. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

vi. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Originality, simplicity, brevity, active verbs, everyday language, decency: as simple as it is very, very hard. It’s a relief in a way to recall that Orwell thought things were pretty damn shitty in his day as well, but the more you read broadly across most elite media platforms these days, the more similar it all sounds. To reverse Orwell’s virtues: so much of it is repetition, complexity, length, passive verbs, endless jargon, barbarism.

I was just reading about the panic that occurred in the American Medical Association, when their journal’s deputy editor argued on a podcast that socio-economic factors were more significant in poor outcomes for non-whites than “structural racism”. As you might imagine, any kind of questioning of this orthodoxy required the defenestration of the deputy editor and the resignation of the editor-in-chief. The episode was withdrawn from public viewing, and the top editor replaced it with a Maoist apology/confession before he accepted his own fate.

But I was most struck by the statement put out in response by a group called “The Institute for Antiracism in Medicine”. Here it is:

The podcast and associated promotional message are extremely problematic for minoritized members of our medical community. Racism was created with intention and must therefore be undone with intention. Structural racism has deeply permeated the field of medicine and must be actively dissolved through proper antiracist education and purposeful equitable policy creation. The delivery of messages suggesting that racism is non-existent and therefore non-problematic within the medical field is harmful to both our underrepresented minoritized physicians and the marginalized communities served in this country.

Consider the language for a moment. I don’t want to single out this group — they are merely representative of countless others, all engaged in the recitation of certain doctrines, and I just want an example. But I do want to say that this paragraph is effectively dead, drained of almost any meaning, nailed to the perch of pious pabulum. It is prose, in Orwell’s words, that “consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated hen-house.”

It is chock-full of long, compounded nouns and adjectives, riddled with the passive voice, lurching and leaning, like a passenger walking the aisle on a moving train, on pre-packaged phrases to keep itself going.

Notice the unnecessary longevity: a tweet becomes an “associated promotional message”. Notice the deadness of the neologisms: “minoritized”, “marginalized”, “non-problematic”. As Orwell noted: “the normal way of coining a new word is to use a Latin or Greek root with the appropriate affix and, where necessary, the -ize formation. It is often easier to make up words of this kind (deregionalize, impermissible, extramarital, non-fragmentatory and so forth) than to think up the English words that will cover one’s meaning.” Go back and see if you can put the words “minoritized” or “non-problematic” into everyday English.

Part of the goal of this is political, of course. The more you repeat words like “proper antiracist education” or “systemic racism” or “racial inequity” or “lived experience” or “heteronormativity”, the more they become part of the landscape of words, designed to dull one’s curiosity about what on earth any of them can possible mean. A mass of ideological abstractions, in Orwell’s words, “falls upon the facts like soft snow, blurring the outlines and covering up all the details.”

Then this: “Racism was created with intention.” Abstract noun, passive voice, vague meaning. Who “created” it? What was the intention exactly? Hasn’t racist tribalism been a feature of human society for tens of thousands of years? They never say. Or this phrase: “purposeful equitable policy creation”. Again: what are they talking about? It is as vague as “doing the work” — and as deliberate as the use of a highly contested term like “structural racism” to define objective reality. These are phrases not designed to say anything real. They are phrases designed to send a message of orthodoxy, and, as Orwell also noted, “orthodoxy, of whatever colour, seems to demand a lifeless, imitative style”. Try reading Slate or Vox or the Huffington Post: the tedium you feel is the tedium of a language rendered lifeless by ideology.

May 15, 2021

QotD: Military history

Things have changed little today in terms of the exclusive Western monopoly of military history. Six billion people on the planet are more likely to read, hear, or see accounts of the Gulf War (1990) from the American and European vantage points than from the Iraqi. The story of the Vietnam War is largely Western; even the sharpest critics of America’s involvement put little credence in the official communiqués and histories that emanate from communist Vietnam. In the so-called Dark Ages of Europe, more independent histories were still published between A.D. 500 and 1000 than during the entire reigns of the Persian or Ottoman Empire. Whether it is history under Xerxes, the sultan, the Koran, or the Politburo at Hanoi, it is not really history — at least in the Western sense of writing what can offend, embarrass and blaspheme.

Victor Davis Hanson, Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power, 2001.

April 28, 2021

QotD: George Orwell’s other novels

[Orwell’s] major work remains canonical, and cited on a daily basis in virtually every context imaginable, appropriately or otherwise. It seems unlikely that virtually any well-read man or woman is a stranger to his two most famous novels, which have established him, even seven decades after his death, as one of the bestselling writers in the English language. But once-popular works such as The Road to Wigan Pier are now in danger of falling into obsolescence, as the social circumstances that Orwell describes seem less and less relevant to a 21st-century readership, and even his great work of Spanish Civil War reportage Homage to Catalonia might be dismissed as a period piece, written with undeniable fire and conviction but saying little to a contemporary audience.

This would be a harsh and rather glib judgement, but many writers have faced worse. The book that suggested Wigan Pier, JB Priestley’s English Journey, was once hugely influential, even being credited with winning Labour the 1945 election, and is now regarded as a quaint piece of social commentary. That Priestley conducted his travels from a chauffeur-driven car, while Orwell willingly subjected himself to filthy evenings in slum bed and breakfasts and hostels, is a telling distinction between the two writers and their approaches: it is also undeniably true that Priestley died at 89, a grand old man of letters, and that Orwell’s premature death was one brought on by the tuberculosis that had affected him for years before his death. Yet Priestley is now remembered mainly for An Inspector Calls, and Orwell remains an iconic figure, beloved by millions. His canonisation was made explicit by a statue of him by Martin Jennings being erected outside Broadcasting House in 2017, complete with the phrase “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear”.

Yet it is doubtful that many of his admirers have read his earlier novels, namely Burmese Days, A Clergyman’s Daughter, Keep the Aspidistra Flying and Coming Up For Air. All four were brought out by the left-wing publisher Victor Gollancz, between 1934 and 1939, and each of them is autobiographical in nature. Burmese Days draws on Orwell’s faintly unlikely time in Burma in the Twenties with the Indian Imperial Police, and A Clergyman’s Daughter uses both his life with his family in Southwold (which appears faintly disguised in the novel as “Knype Hill”) and his days tramping for its narrative. Keep the Aspidistra Flying finds Orwell mining his experiences in the lower reaches of the London literary scene, including his time working in a bookshop in Hampstead, and Coming Up For Air, written while Orwell was recuperating in Marrakesh, is suffused with an intense nostalgia for an England that may never have really existed, but is of a piece with the fascination, and repulsion, for the tenets of “Englishness” that Orwell wrote about over and over again in his essays and reportage.

Alexander Larman, “The lesser-known Orwell: are his novels deserving of reappraisal?”, The Critic, 2021-01-07.

March 25, 2021

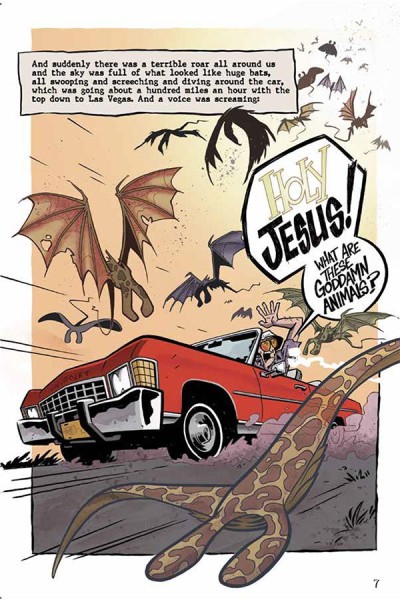

Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

I first read Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in the late 1970s and being as callow and inexperienced as most teenagers, I took it for a mostly factual exploit (along with many older readers who didn’t have my excuse for gullibility). I passed the book on to one of my friends who became mildly obsessed with “Raoul Duke” and the adventures recounted in the book. I’ve long since lost touch with him, but I’m sure he’d be horribly disappointed to discover that Thompson probably imagined 90% of it:

We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold. I remember saying something like “I feel a bit lightheaded; maybe you should drive …” And suddenly there was a terrible roar all around us and the sky was full of what looked like huge bats, all swooping and screeching and diving around the car, which was going about a hundred miles an hour with the top down to Las Vegas.

From the outset, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is an outrageous and darkly amusing tale of two crazed men turned loose in the world’s capital of decadence. Raoul Duke and Doctor Gonzo, clearly based upon Thompson and Acosta, are carrying a veritable pharmacopoeia in the trunk of their rented car, and throughout the novel they abuse a litany of substances as they stumble through casinos, bars, and hotels terrorising staff and patrons alike. Though Duke and Gonzo are, like the real Thompson and Acosta, tasked with covering the Mint 400, their assignment is quickly lost in the carnage. Near the end of the book, Duke admits he “didn’t even know who’d won the race.”

If you are unfamiliar with Thompson’s work, you may wonder why it matters that their efforts to complete a minor assignment ended in failure. Authors like Ernest Hemingway had mined their journalistic experience for material to incorporate into their fiction, so it is hardly unusual that Thompson would find inspiration for a novel whilst covering the Mint 400. But his approach with this book went beyond mere inspiration. Throughout Fear and Loathing, reality and imagination are blurred to the extent that no one really has much idea of what really happened on their trip.

[…]

In this letter, he made the startling confession that Fear and Loathing had not merely exaggerated the debauchery that took place in Vegas, but that there had in fact been no drugs at all. Could this really be true? Was the most notorious drug book of its era really inspired by a drug-free journey?

Before we can answer that, it is important to note the chronology of events on which the book was based. Whilst the book portrays the two men tearing apart hotels and casinos over a period of several days, there were in fact two distinct trips. First, they went to cover the Mint 400 on Mach 21st–23rd, then they returned for the National District Attorneys’ Conference on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs on April 25th–29th. Thompson simply rolled the two events together into a single narrative. The evidence suggests that, during the first trip, Thompson and Acosta drank heavily and perhaps smoked a little pot, but certainly did no serious drug-taking. The famed pharmacopeia in the trunk of their convertible was fictitious:

The trunk of the car looked like a mobile police narcotics lab. We had two bags of grass, seventy-five pellets of mescaline, five sheets of high-powered blotter acid, a salt shaker half full of cocaine, and a whole galaxy of multi-colored uppers, downers, screamers, laughers … and also a quart of tequila, a quart of rum, a case of Budweiser, a pint of raw ether and two dozen amyls.

As tempting as it is to believe that this existed, it was a product of Thompson’s prodigious imagination. He was, however, keen to keep his readers in the dark, hence his letter to Silberman and the inclusion of his photo on the back cover. Since childhood, he had been obsessed with appearing as an outlaw, yet real outlaws never explicitly said that’s what they were. They merely hinted at it.

Of course, Thompson’s “drug-diet” did consist of various illegal substances, which made his descriptions of their effects rather convincing, but not only did he remain mostly drug-free in Vegas, he also wrote the novel with little more than beer and tobacco in his system. Back home in Colorado, he polished his story carefully through many drafts. The result was a far more intelligent and coherent work than almost anything else he published.

It was only during the second of the two trips that they began to consume drugs, but even then their indulgence was mild when compared with Duke and Gonzo’s extravagant excesses. They had marijuana, a few pills, and possibly some mescaline, but nothing else. His descriptions of LSD came from experiments several years earlier, the parts about adrenochrome were entirely fabricated, and — surprisingly — Thompson had not yet tried cocaine by 1971.