Jill Bearup

Published 23 Jun 2025Listen, nobody asked for a history of fanfiction but here we are regardless. From Helen of Troy fix-it fic to Holmes fans unsubscribing en masse when the detective was killed in The Final Problem, fandom has always been this chaotic, and fanfiction has always been with us. In one form or another.

00:00 Did you ask for this? Nah.

01:20 Ancient authors ripping off other ancient authors

03:06 Virgil was a Homer fanboy

04:10 Dante was a Virgil fanboy

05:18 Don Quixote and the Case of the Unauthorised Sequel

08:01 The Statute of Anne

12:35 Gulliver’s Travels NSFW fanart

14:40 Geniuses and Originality

16:51 The Berne Convention

17:20 Character Vibes are not Copyrightable

20:46 The First Modern Fandoms (were Genuinely Unhinged)Link to Der Spiegel article on copyright and innovation: https://www.spiegel.de/international/…

June 24, 2025

Fandom Has Always Been UNHINGED

June 22, 2025

Delaying Mark Carney’s next book

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte outlines the various oddities of Mark Carney’s next book to market:

Three years ago, long before he declared himself a politician, Mark Carney published Value(s), his attempt at solving some of the world’s biggest problems: income inequality, climate change, systemic racism, etc. The book was reasonably well received. It sold well. A sequel was in order.

Announced last year, The Hinge: Time to Build an Even Better Canada was ostensibly Carney’s attempt to address Canada’s biggest issues, and perhaps to position himself as our future leader. The book was set for release in May 2025. Events interceded and Carney was elected prime minister on a far tighter timeline than anyone, including his publisher, could have imagined. Publication of The Hinge was delayed. An anonymous source told the Toronto Star Carney was too busy politicking to finish the final edits on the book. I heard the delay had more to do with campaign finance rules that would consider a book publicized or released in election season as political advertising. Anyway, a new release date was set for July 1. Amazon now has The Hinge coming next January.

Carney’s political opponents have been enjoying the delay. Critics both left and right have attributed it to the difficulty of squaring positions taken by Carney a year or two ago with positions he espoused during the campaign and, more recently, as prime minister.

I don’t doubt that Carney’s politics have moved over the last six months. And I wouldn’t be surprised if his second book is being rewritten in whole or in part. I don’t have a problem with that. Much has happened, both in Canada and south of the border. We’ve all been reconsidering our positions.

My problem with Carney’s conduct is not that he’s revising his manuscript, if he is, but that he’s not revising his publishing contract.

The Hinge is set to be published by Signal. Signal is a division of McClelland & Stewart. M&S is a division of Penguin Random House Canada. PRHC is a division of Penguin Random House LLC, corporate headquarters at 1745 Broadway, 3rd Floor, New York, New York, 10019.

Penguin Random House LLC is owned by Bertelsmann, a media conglomerate in Gütersloh, Germany, but legally and operationally, it is a US company. Its executive leadership, including CEO Nihar Malaviya, works out of the above address. Strategy and publishing priorities are set in New York, and profits in PRH’s many far-flung international divisions flow to New York. So the prime minister of Canada is publishing his book with the Canadian branch plant of a US company.

Other recent prime ministers have done the same. Justin Trudeau published Common Ground with HarperCollins. Steven Harper published Right Here, Right Now with Signal, and his forthcoming memoir sits there, too. Jean Chretien released My Stories, My Time with Random House Canada. Most of our politicians have published with branch plants of American firms.

I should add that many of our best writers publish at these same branch plants, if not directly with US publishers. (Even middling scribblers like me have published directly in the US.)

But, again, the world has changed. To quote no less an authority than Mark Carney, Canada’s old relationship with the US, “based on deepening integration of our economies and tight security and military cooperation, is over”. We need to “fundamentally reimagine our economy”, “retool” our industry, and enhance our self-sufficiency.

He sees our cultural relationship with the US as part of this project. From the Liberal platform: “In this time of crisis, protecting Canada means protecting our culture, our journalism, our perspectives. The Americans have threatened our sovereignty and issued inflammatory statements about our economy; we need to be able to tell a story that fights back.”

Right under the cultural section of the platform was a “Buy Canadian” plank. “At a time when our economy is under threat, consumers want to do their part as patriotic Canadians, buying things that are truly made here.” Team Carney promised to make it easier to determine what is and isn’t a Canadian product and prioritize made-in-Canada suppliers in every sector of the economy, limiting bidders from foreign suppliers, and so on.

So it’s “eLbOwS uP!” for the voters, but carry on publishing your next book through a US-owned subsidiary, eh? You have to admit they wear their hypocrisy proudly.

May 31, 2025

QotD: Explaining the science to the non-scientific layperson

There’s a famous video in which Richard Feynman is asked by a BBC journalist if he can explain magnetism to him, and Feynman pauses for a moment and says “no”. The journalist is totally incredulous, and demands to know what Feynman means by that, and the great scientist tells him that he knows so little of the basics, and magnetism is so deep and so tricky,1 that it would be impossible to explain much of anything without either misleading him or giving him a false understanding.

I’ve always thought that nearly all pop science books fall into one version or another of this trap. Either they abandon all attempts at explaining the difficult concept in simple terms, or they simplify and elide so much as to become actively misleading.2 I call the latter horn of the dilemma “string theory is like a taco”-syndrome, and it’s by far the more common failure case. This is because undersimplification makes your audience feel dumb, while oversimplification makes them feel smart, so you sell a lot more books by oversimplifying. Unfortunately the effects on the audience of oversimplification are far more dangerous and insidious. After reading something impenetrable, you at least still know that you don’t really understand it, so there’s still a chance for you to go on and learn it some other way. Reading an oversimplified explanation, however, can fool you into thinking that you now grasp the concept, when in reality all you’ve grasped is a lossy analogy that will lead you astray.

All of which is to say I think it’s pretty impressive how well [author David] Reich does at diving into some of the real statistical meat of his techniques while still making them comprehensible to a smart layman. He has the gift that the greatest scientific expositors possess of being able to communicate in simple terms what it is that makes a problem hard, and then also giving you the broad strokes of an elegant solution to that hard problem. He doesn’t pretend that he hasn’t left anything out, instead he points out exactly where he’s glossed over details, so that you can go back and look them up if you want. This doesn’t sound all that impressive, but it’s actually really freaking hard to pull off, especially in a field that’s new and hence hasn’t been reformulated and recondensed a hundred times until it’s turned into a crystalline version of itself.

Okay, what was your favorite interesting genetic fact that this book taught you about a contemporary population? Mine was definitely that the various Indian jatis are as genetically distinct from one another as the Ashkenazi Jews are from everybody else. Not one group, but hundreds and hundreds of groups, all living in close proximity to each other, have gone millennia with incredibly minimal genetic mixing. How is that possible? It makes me take some of the assertions made by classical Indian texts a little bit more seriously.

Jane Psmith and John Psmith, “JOINT REVIEW: Who We Are and How We Got Here, by David Reich”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-05-29.

1. It always bothered me when people ragged on Insane Clown Posse for expressing humility and awe at magnets. In fact their attitude is exactly the appropriate one. Back when ICP were in the news more often, I made a minor hobby of demanding that anybody who made fun of them explain magnets scientifically to me on the spot. Nobody ever succeeded.

2. And sometimes, remarkably, a pop science book manages to make both mistakes at the same time. I’m reminded of Edward Frenkel’s horrible book Love & Math, which is full of passages like: “Think of the Hitchin fibration as a box of donuts, except that there are donuts attached not only to a grid of points in the base of the carton box, but to all points in the base. So we have infinitely many donuts — Homer Simpson would sure love that! It turns out that the mirror dual Hitchin moduli space, the one associated to the Langlands dual group, is also a donut topic/fibration over the same base. Donuts. Is there anything they can’t do?”

December 29, 2024

QotD: Churchill as author and Prime Minister

“Writing a book is an adventure. To begin with it is a toy, an amusement; then it becomes a mistress, and then a master, and then a tyrant.” Those owning a business plan, devising an advertising proposal, plotting a military stratagem, drafting an architectural blueprint, painting a picture, crafting sculpture or ceramics, penning a volume, sermon or speech — or editing The Critic — will, I suspect, be nodding in recognition of this.

The words were those of Winston Churchill, the 150th anniversary of whose birthday, 30 November 1874, falls this year. In addition to submitting canvases to the Royal Academy of Arts under the pseudonym David Winter — which resulted in his election as Honorary Academician in 1948 — and twice being Prime Minister for a total of eight years and 240 days, he has merited far more biographies than all his predecessors and successors put together. This summer I completed one more volume to add to the vast collection. My purpose here is less to blow my own trumpet than to ponder why Churchill remains so popular as a subject and survey what is new in print for this anniversary year.

It is tempting to see his career through many different lenses, for his achievements during a ninety-year lifespan spanning six monarchs encompassed so much more than politics, including that of painter. The only British premier to take part in a cavalry charge under fire, at Omdurman on 2 September 1898, he was also the first to possess an atomic weapon, when a test device was detonated in Western Australia on 3 October 1952. Besides being known as an animal breeder, aristocrat, aviator, big-game hunter, bon viveur, bricklayer, broadcaster, connoisseur of cigars and fine fines (his preferred Martini recipe included Plymouth gin and ice, “supplemented with a nod toward France”), essayist, gambler, global traveller, horseman, journalist, landscape gardener, lepidopterist, monarchist, newspaper editor, Nobel Prize-winner, novelist, orchid-collector, parliamentarian, polo player, prison escapee, public schools fencing champion, rose-grower, sailor, soldier, speechmaker, statesman, war correspondent, war hero, warlord and wit, one of his many lives was that of writer-historian.

Most of his long life revolved around words and his use of them. Hansard recorded 29,232 contributions made by Churchill in the Commons; he penned one novel, thirty non-fiction books, and published twenty-seven volumes of speeches in his lifetime, in addition to thousands of newspaper despatches, book chapters and magazine articles. Historically, much understanding of his time is framed around the words he wrote about himself. “Not only did Mr. Churchill both get his war and run it: he also got in the first account of it” was the verdict of one writer, which might be the wish of many successive public figures. Acknowledging his rhetorical powers, which set him apart from all other twentieth century politicians, his patronymic has gravitated into the English language: Churchillian resonates far beyond adherence to a set of policies, which is the narrow lot of most adjectival political surnames.

“I have frequently been forced to eat my words. I have always found them a most nourishing diet”, Churchill once quipped at a dinner party, and on another occasion, “history will be kind to me for I intend to write it”. Yet “Winston” and “Churchill” are the words of a conjuror, that immediately convey a romance, a spell, and wonder that one man could have achieved so much. It is an enduring magic, and difficult to penetrate. In 2002, by way of example, he was ranked first in a BBC poll of the 100 Greatest Britons of All Time — amongst many similar accolades. A less well-known survey of modern politics and history academics conducted by MORI and the University of Leeds in November 2004 placed Attlee above Churchill as the 20th Century’s most successful prime minister in legislative terms — but he was still in second place of the twenty-one PMs from Salisbury to Blair.

Peter Caddick-Adams, “Reading Winston Churchill”, The Critic, 2024-09-22.

December 26, 2024

QotD: The essence of journalism

Journalism is the craft of filling in the white bits between the advertisements.

It’s not a profession, it’s not a calling and it has no public purpose. Trial and error has shown that peeps out there just won’t go out and buy booklets of adverts. They won’t even pay all that much attention to free books of them stuffed through their letterboxes as local freesheets show.

In order to get people to see the piccies of fine cavalry twill trousers (an ad that has been running beside the Telegraph crossword for at least four decades), or to drool over offers of lushly organic bath salts, experience has indicated that someone needs to be employed to write about the footie – see that parrot bein’ sick? – or the weather – cloudy with a chance of meatballs – or the thespian who should only have been stepped out with – Meghan Steals Our Prince! – or you know what they’re doing with your money – Tax Rise Shocker! – to fill in the blanks between the commercial offers.

And that’s it. That’s what we do.

We can even prove this. The editorial line of absolutely every publication is one that follows the prejudices of its readers. When setting up a new one the big question is, well, who are we going to appeal to? Not what truths are we going to tell but who will look at the ads based upon the truths we decide to tell.

All that speaking truth to power, interrogation of structures and inequalities, that’s for the awards season. It has as much to do with reality as calling politicians statesmen – entirely irrelevant to the working day and something more suited to those dead.

Entirely true that journalism comes in flavours, even layers, styles and stratified along socioeconomic lines. But then so do restaurants come in manners that appeal to different audiences despite their output all ending up in the same place – the U-bend – some limited number of hours after consumption.

Journalism is simply entertainment that is, journalists just those who do so with words. There is a market for that truth-telling to power stuff, just as there is one for vegan meals. But they’re both limited to those who are entertained by such which is why Maccy D’s bestrides the world and the Mail and The Sun outsell Tribune, Counterpunch and Salon.

Tim Worstall, “The Grandiosity Of Modern Journalism”, Continental Telegraph, 2020-05-02.

December 13, 2024

The influence of Mesopotamian cultures on ancient Greece

James Pew and Scott Miller begin their series on the history of western education by looking at the way Greek civilization was influenced by the Mesopotamian cultures who used cuneiform writing for three thousand years:

An example of a clay tablet inscribed with cuneiform text (in this case, a portion of the Epic of Gilgamesh)

In the 19th century, three new discoveries began to militate against “the image of pure, self-contained Hellenism”. They were: “the reemergence of the ancient Near East and Egypt through the decipherment of cuneiform and hieroglyphic writing, the unearthing of Mycenaean civilization, and the recognition of an Orientalizing phase in the development of archaic Greek art”.

To sketch the significance of just one of these discoveries, what the discovery of cuneiform writing means for the history of writing and literature, we have with cuneiform not only the first writing system in human history, but also the longest running (it was in use for over 3,000 years); cuneiform texts are, at the same time, the best preserved and most numerous textual records from the ancient world by far (there are hundreds of thousands of cuneiform documents in museum archives today because the signs were inscribed on clay tablets which preserve better across time than other materials used for writing in ancient times). This complex writing system, consisting of thousands of signs, was developed first in Mesopotamia by the Sumerians and, subsequently, it was adopted by the Akkadians, Babylonians and Assyrians in the same area. It emerged c. 3200 B.C. as a response to social and economic complexities generated by the world’s first cities: invariably, the impetus to create a writing system comes down to the need to document and track the transfer of food stuffs, material goods, temple offerings, and so forth, the administration of complex urban society. On the other hand, written literature in the form of myth, poetry and the like, are secondary developments that may follow a long time later (if at all). In centuries to follow, Mesopotamian scribes would begin to write down epic tales telling the exploits of heroic kings, such as Gilgamesh, along with hymns and prayers to the Mesopotamia gods, incantations to ward off demons and diseases, texts containing lists of known phenomena, proverbs, reports of astrological phenomena and their omens, medical and magical texts to be used by the healing expert, and many text types besides.

On the Question of Greek Borrowing from the more ancient East: This series will delve into the work of many of these cutting-edge historical scholars who follow the evidence from Orient to Occident. Academic’s like Albin Lesky, M.L. West, Walter Burkert, Margalit Finkelberg, Harald Haarmann, Daniel Ogden, Mark Griffith, and more.

It is no easy task to establish links between Greece and ancient Near Eastern civilizations, and the difficulty has to do with more than vast expanses of time and space. Typically, modern scholars of classical Greece have a tendency to “transform ‘oriental’ and ‘occidental’ into a polarity, implying antithesis and conflict”. According to Burkert, it was not until the Greeks fought back the Persian Empire that they became aware of their distinct identity (as separate from the orient). In addition, it was not until many years later, during the crusades, that “the concept and the term ‘Orient’ actually enter(ed) the languages of the West”. The reluctance on the part of many scholars to accept a universal conception of cultural development which involved “borrowing”, “loan words”, and “cultural diffusion” amongst the different ancient peoples living in both the Near East and the Aegean regions, is due to intellectual currents that first took shape in Germany over two centuries ago. In Burkert’s words, “Increasing specialization of scholarship converged with ideological protectionism, and both constructed an image of a pure, classical Greece in splendid isolation”.

It was essentially a trio of academic fads that “erected their own boundaries and collectively fractured the Orient-Greece axis”. The first was the breaking apart of theology and philology. Until well into the 18th century, “the Hebrew Bible naturally stood next to the Greek classics, and the existence of cross-connections did not present any problems”. The second was the rise of the ideology of Romantic Nationalism, “which held literature and spiritual culture to be intimately connected with an individual people, tribe, or race. Origins and organic development rather than reciprocal cultural influences became the key to understanding”. And the third was the discovery by linguistic scholars of “Indo-European”, the “common archetype” of most European languages (as well as Persian and Sanskrit).

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff offered a “scornful assessment” indicative of the faddish and far more isolated conception of ancient Greece in 1884: “the peoples and states of the Semites and the Egyptians which had been decaying for centuries and which, in spite of the antiquity of their culture, were unable to contribute anything to the Hellenes [the Greeks] other than a few manual skills, costumes, and implements of bad taste, antiquated ornaments, repulsive fetishes for even more repulsive fake divinities …” A common take at the time which would later prove to be quite incomplete. It should be noted that Romantic Nationalism, coupled with the discovery of Indo-European (which demonstrates no link between European and Semitic languages) seems to have contributed to what gave “anti-Semitism a chance”. Tragically, it was at the point when the Jews were finally being granted full legal equality in Europe when national-romantic consciousness and the rejection of orientalism helped set the stage for the escalation in Jewish persecution that eventually led to the horror of horrors: the Holocaust.

The Mesopotamians would never, as the later Greeks did c. 600 B.C., formulate an abstract concept of “nature” and analyze phenomena as having a natural developmental explanation rather than the traditional explanation (that being, e.g. the gods made it so). Thus, they would never develop philosophy or science as we think of it, and so there are certain categories of analysis and knowledge that are uniquely Greek in the ancient world. However, as the innovators of a form of agrarian society that was productive and sophisticated enough to sustain the world’s first cities, Mesopotamians needed to be able to examine and quantify time (in order to know when to plant) and so they developed the lunar calendar of 12 months, they developed the 12 double-hour day, they gave names to the observable planets and charted the night sky into constellations; They needed to be able to measure physical space and allot pieces of land to land owners, and so they created the world’s earliest form of basic geometry. The types of knowledge just named are the types of knowledge that scholars believe would have been of interest to the Greeks, and, indeed, many suspect that iron age Greeks borrowed these insights from the Babylonians. Whether the Greek story of Heracles could have been influenced by Mesopotamian hero epics such as the Epic of Gilgamesh is a more contentious — though intriguing — topic.

So, how did Greece find itself in a position to receive the baton of civilization and even to carry it further forward? Because of the great work of modern scholars, we know that an informal but early (proto) archetypal version of education (not yet organized education) begins in the Mediterranean, in archaic Greece, before the classical period. Even before this, although it is not exactly clear as to the extent, it has been determined that Bronze Age Greek cultures located around the area of the Aegean sea (also known as Aegean Civilization) – the Mycenaean on mainland Greece, the Minoan on the island of Crete and the Cyclades (also known as the Aegean Islands) – were not only in contact with each other, but also with neighboring civilizations: Egypt, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, and the Levant.

December 11, 2024

QotD: Simon Leys on George Orwell

… the very title of one of his essays, “The Art of Interpreting Non-Existent Inscriptions Written in Invisible Ink on a Blank Page”, tells you the essentials of what you needed to know about the decipherment of publications coming out of China and the kind of regime that made such an arcane art necessary, and why anyone who took official declarations at face value was at best naive and at worst a knave or a fool.

What Leys wrote in 1984 in a short book about George Orwell might just as well have been written about him: “In contrast to certified specialists and senior academics, he saw the evidence in front of his eyes; in contrast to wily politicians and fashionable intellectuals, he was not afraid to give it a name; and in contrast to the sociologists and political scientists, he knew how to spell it out in understandable language.”

Leys drew a distinction between simplicity and simplification: Orwell had the first without indulgence in the second. Again, the same might be said of Leys — who, of course, like Orwell, had taken a pseudonym, and with whose work there were many parallels in his own.

But immense as was Leys’s achievement in destroying the ridiculous illusions of Western intellectuals, as Orwell had tried to do before him, it was a task thrust upon him by circumstance rather than one that he would have chosen for himself. He was by nature an aesthete and a man of letters, and I confess that great was my surprise (and pleasurable awe) when I discovered that he was, in addition to being a great sinologist, a great literary essayist.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Rare and Common Sense”, First Things, 2017-11.

December 10, 2024

Microsoft has launched a publishing arm called “8080 Books” – AI-generated books anyone?

Ted Gioia notices that Microsoft and other tech companies are moving into book publishing, likely as a way to generate some additional revenue from their vast investments in artificial intelligence ventures over the last several years:

I never expected Microsoft to enter the book business.

But on November 18, this huge tech company quietly announced that it is now a publisher. But there was an interesting twist.

Microsoft is “not currently accepting unsolicited manuscripts”.

Let’s be totally fair. Nobody at Microsoft claims that it plans to replace human writers with AI slop. But this company has invested a staggering $13 billion in AI — it’s their top priority as a corporation.

So what you do think their goals are in the book business?

If you’re looking for a clue, I note that Microsoft’s publishing arm is called 8080 Books. Yes, they named it after the 8080 microprocessor.

How charming!

And just a few hours after Microsoft announced this move, TikTok did the exact same thing.

According to The Bookseller:

ByteDance, the company behind the video-sharing platform TikTok, has announced that it will start selling print books in bookshops from early next year, published under its imprint, 8th Note Press. 8th Note Press will work in partnership with Zando to publish print editions and sell copies in physical bookstores starting early 2025.

Here, too, nobody is claiming that they will replace humans with bots. But why would a company that has built its empire with online social media have any interest in the slow and stodgy business of selling printed books on paper?

Oh, by the way, TikTok’s parent is investing huge sums in AI. The company has even found a way around export controls on Nvidia chips. Just a few weeks before entering the book business, ByteDance’s sourcing of AI tech from Huawei was leaked to the press.

And as if these coincidences weren’t enough to alarm you, another AI publishing development happened at this same time — but (here too) with very little coverage in the media.

Tech startup Spines raised $16 million in seed financing for an AI publishing business that aims to release 8,000 books per year.

Here, too, the company says that it wants to support human writers. Maybe it will run a new kind of vanity publishing business. But is that a sufficient lure to attract $16 million in seed financing?

It’d be a rearguard action, but it’d be nice to have a requirement that publishers disclose when published works are partly or wholly AI-extruded, wouldn’t it? It would certainly help me to avoid buying books or magazines where AI hallucinations may occur in key sections …

December 6, 2024

Victoria’s Canada through the eyes of British visitors

In UnHerd, Michael Ledger-Lomas considers what earlier British visitors to Canada after Confederation wrote about their experiences:

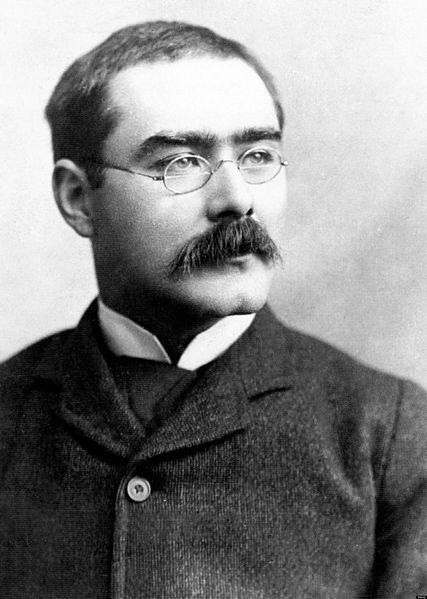

Portrait of Rudyard Kipling from the biography Rudyard Kipling by John Palmer, 1895.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

… The re-election of Donald Trump, who has already daydreamed about turning Canada into his 51st state, might even rekindle Tory patriotism. After all, their Victorian ancestors created the dominion of Canada in 1867 to keep British North America from the clutches of the United States.

A longer view shows that Canada has allured but also vexed British observers ever since its creation. The Edwardian era produced an especially rich crop of writings on Canada. In 1887, the year of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, the first train from Montreal pulled into Vancouver. This completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) had persuaded the Crown colony of British Columbia to join in the new federation. In expanding Canada, the CPR also made it easier for British people to see the country. Having crossed from Liverpool to Montreal on a fast liner, they could visit most of its major cities, which were found on or near the railway.

Literary celebrities did so in enviable conditions. The CPR’s bosses loaned the poet Rudyard Kipling his own carriage in 1907, so he could travel in comfort and at his own speed. His impressions, which appeared in newspapers and then as Letters to the Family (1908), make for particularly resonant reading today. Although a man of strong prejudices, he had seen the country up close, rather than merely retweeting allegations about it, and was prepared to be surprised as well as disappointed by it.

Kipling’s contemporaries travelled with heavier and very different ideological baggage than we carry today. It was not wokery that worried them, but irreligion and greed, two poisons that had crept north from America. When the clergyman Hensley Henson steamed into Vancouver, in July 1909, he was horrified to see its beaches plastered with “vulgar advertisements”. The further [East] he travelled, the worse things became. The Anglican clergy were “weaklings” who made no dent on a materialistic society. Winnipeg was given over to “graft”. Young people in Ontario spoke like gum-chewing Yankees. Quebeckers were despoiling their province by setting up hydroelectric dams on its waterfalls.

Kipling did not share Henson’s churchy desire to scold his Canadian hosts. He was a cheerful freethinker who considered materialism a necessary part of nation-building. Canada had “big skies, and the big chances”: he admired its railway workers and lumberjacks for their insouciant and sometimes drunken swagger. Boom towns like Winnipeg excited him: he loved to see office blocks rise and streets flare with natural gas lamps; he lost considerable sums speculating on Vancouver real estate.

What worried him was rather Canada’s fading strategic commitment to the Empire. The modern Right understands Canada as a battleground for the values of “the West”. Kipling, who had married an American and lived for some years in Vermont, naturally believed in and did much to formulate the fervent if vague sense that English-speaking peoples share a civilisation. Yet this did not weaken his overriding concern for the political cohesion of the British Empire. Canada’s failure to join as enthusiastically in Britain’s recent war against the rebellious Dutch Boers of South Africa as he would have liked weighed on him — so much so that he kept calling the prairie the “veldt”. Kipling regarded the scepticism of Liberals and Socialists at home about whether the Empire offered value for money as a “blight”: now this “rot” seemed to be spreading like Bubonic plague, “with every steamer” to Canada.

The way to draw the dominion back to the motherland was to fill it with English settlers who shared his distaste for domestic Socialism. The dilution of English Canada worried Kipling. He allowed the Francophone Catholics of Quebec their differences — he found their basilicas romantic — but the policy of settling the prairies with hardy Slavs from the Habsburg and Russian Empires appalled him. These “beady-eyed, muddy-skinned, aproned women, with handkerchiefs on their heads and Oriental bundles in their hands” could never assimilate to English Canada. Nor did he care that many were fleeing oppression: people who renounce their country have “broken the rules of the game”.

November 26, 2024

Orwell is more relevant now than at any time since his death

I’m delighted to find that Andrew Doyle shares my preference for Orwell the essayist over Orwell the novelist:

It is not without justification that Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) have become the keystones of George Orwell’s legacy. Personally, I’ve always favoured his essays, more often quoted than read in full. I recently wrote an article about his essays for the Washington Post, focusing on their relevance to today’s febrile political climate. You can read the article here. I would draw particular attention to the multitude of comments from left-wing readers who are apparently outraged at my argument (actually, Orwell’s argument) that authoritarianism is not specific to any one political tribe. They seem oddly determined to prove the point.

Orwell is unrivalled on the topic of the human instinct for oppressive behaviour, but his essays are far more wide-ranging than that. In these little masterworks, one senses a great thinker testing his own theses, forever fluctuating, refining his views in the very act of writing. The essays span the last two decades of his life, offering us the most direct possible insight into this unique mind.

[…]

I find Orwell’s disquisitions on literature to be among his most rewarding. “All art is propaganda”, he declares in his extended piece on Charles Dickens (1940) [link]. This conviction, flawed as is it, accounts for his determination to focus less on Dickens’s literary merits and more on his class consciousness, which is found wanting. Even better is Orwell’s rebuttal to Tolstoy’s strangely literal-minded reading of Shakespeare (1947’s “Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool” [link]), which is so rhetorically deft that it seems to settle the matter for good.

Another impressive essay, “Inside the Whale” (1940) [link], opens with a glowing assessment of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer (1935) but soon broadens its range to cover many contemporary novelists and their approach to social commentary. The title is a reference to Miller’s remarks on the Biblical tale of Jonah, suggesting that life inside the whale has much to recommend it. Orwell puts it this way:

There you are, in the dark, cushioned space that exactly fits you, with yards of blubber between yourself and reality, able to keep up an attitude of the completest indifference, no matter what happens.

Orwell invites us to imagine that the whale is transparent, and so writers of Miller’s ilk may snuggle contentedly within, observing without interacting, recording snapshots of the world as it bounces by. This kind of inaction is anathema to Orwell, whose every written word seems to be driving towards the enactment of social change.

Orwell’s essays often serve as a cudgel to batter his detractors. He dislikes homosexuals, or those “fashionable pansies” who lack the masculine vigour to take up arms in defence of their country. He displays a similar lack of patience for the imperialistic middle-class “Blimps” and the anti-patriotic left-wing intelligentsia, or indeed anyone who adheres slavishly to any given political ideology. His work bears much of the stamp of the old left; that mix of social conservatism and economic leftism that we see most powerfully expressed in his 1941 essay “The Lion and the Unicorn” [link]. Bad writing is also a recurring bugbear; Orwell’s loathing of cliché and “ready-made metaphors” is one of the reasons his own prose style is so effervescent.

[…]

When Orwell pessimistically refers to “the remaining years of free speech”, one cannot help but be reminded of the increasingly authoritarian tendencies of today’s British government. He expresses irritation that more writers are not wielding their pens in the service of improving society. His own work, by contrast, is what he would term “constructive”, profoundly moral, and purposefully crafted in the hope of actuating real-world change. While other writers resigned themselves to a life inside the whale, Orwell was determined to cut his way out.

November 12, 2024

“Nice business ya got there, Patreon. Wouldn’t want anything to happen to it …”

Above the paywall, Ted Gioia discusses Apple’s latest attempt to cut itself a nice big middleman’s slice of the indy creator market by putting the thumbscrews to Patreon:

Can Apple really charge a 30% tax on indie creators?

What Apple is now doing to indie creators is pure evil — but this story has received very little coverage. Journalists should pay attention, because they are under threat themselves.

Apple is now putting the squeeze on Patreon, a platform that supports more than a quarter of a million creators — artists, writers, musicians, podcasters, videographers, etc.

These freelancers rely on the support of more than 8 million patrons through Patreon, which charges a small 8-12% fee. Many of these supporters pay via Patreon’s iPhone app.

Earlier this year, Apple insisted that Patreon must pay them a 30% commission on all new subscriptions made with the app. In other words, Apple wants to take away close to a third of the income for indie creators — almost quadrupling their transaction fees.

This is the new business model from Cupertino, and it feels like a Mafia shakedown. Apple will make more from Patreon than Patreon does itself.

The only way for indies to avoid this surcharge is by convincing supporters to pay in some other way, and not use an iPhone or Apple tablet.

This is what happens when Apple decides to treat a transaction as an “in app payment” — as if an artist’s entire vocation is no different than a make-believe token in a fantasy video game.

But you can easily imagine how almost anything you do with your phone could be subject to similar demands.

I’ve been very critical of Apple in recent months. But this is the most shameful thing they have ever done to the creative community. A company that once bragged how it supported artistry now actively works to punish it.

September 13, 2024

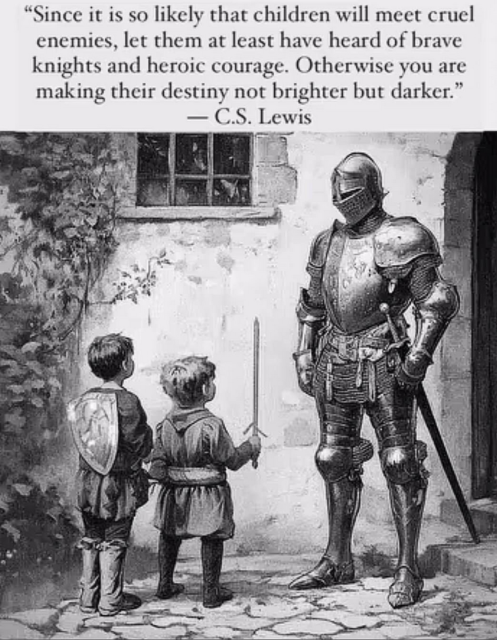

Fiction should have heroes, not merely the morally ambivalent “heroes” modern writers prefer

Tom Knighton is nostalgic for some of the books and movies of his youth, which often had an actual hero you could root for:

Somewhere along the way, fiction started changing.

In my childhood, the nihilism that seems to be so common today wasn’t really a thing. We had grand adventures with heroes who might not have been perfect but were still heroes.

Today, we have a lot of fiction where no one is really the good guy. Rings of Power has been trying to humanize the orcs, making all the good races of Middle Earth darker than they were. Game of Thrones saw just about every truly heroic character killed while so many of the despicable characters lasted until the end.

And that’s a problem. Why?

Well, let’s start with this bit from C.S. Lewis:

Now, I grew up in the era of Rambo and John McClain. I had tough-guy heroes and I also had those that were just regular folks thrust into bad situations.

But there were always good guys and there were always dark forces at work.

The world is more muddied than that, sure, but entertainment doesn’t have to reflect reality perfectly. I mean if that were true, how did Lord of the Rings do so well? Elves and orcs and uruk-hai aren’t exactly real, now are they? Neither are hobbits, Jedi, terminators, or any of a million other fictional creations.

Yet what existed in all of those stories were good guys fighting to put down the evil that arose.

As Lewis argues, it taught my generation and those before and right after mine that cruel enemies can be defeated.

Today, though, we see all too many stories where the enemies prevail, where good fails to triumph over evil, and evil is allowed to remain.

For a while, there was a certain amount of shock value to that. This was when this was the exception rather than a normal thing you would see. It was that moment at the end when you realize the good guy lost despite their best efforts, that revealed at the end that the hero who sacrificed himself to kill the bad guy failed to actually kill him.

August 29, 2024

QotD: The Price of Speed

Recently, over lunch, Mrs. Muros regaled me with tales of authors who treat their readers to several new novels a year. As she waxed rhapsodic on the subject of the people who put the “p” in “prolific”, I scribbled notes on a credit card receipt. “Why is it”, I wrote, “that these ink-strained Atalantas can fill several pages with reasonably readable prose in the time it takes me to assemble a simple Substack post?”

The answer, I mused, might have something to do with sex. All of the authors mentioned by My Yankee Sweetheart, after all, were fully paid-up members of the distaff half of humanity. Could it be that my words fail to flow like summertime honey because my brain has been pickled in androgens? Or, to be somewhat less of a bio-Calvinist, could it be that my refusal to engage in the formal study of literature — a policy which owed much to my belief that the subject was “for girls” — left me bereft of some of the most useful tools of the writer’s trade?

Later that day, as I ransacked back issues of obscure journals in the hope of finding an uncooperative fact, a warm yellow bulb of incandescent understanding appeared above my head. ‘Twas not the writing that slowed me down, I realized, but the research. Indeed, were it not for the pesky puzzle piece I was trying to find, my article would have been done and dusted well before The Love of My Life and I sat down to our midday meal.

Before it faded, my wee epiphany bore two sprogs. The elder of these reminded me that, like other forms of mass production, the prodigious productivity of the quill-drivers in question owed much to the avoidance of novelty. That is, they were able to write so much because, in effect, they made repeated use of familiar formulae, tried-and-true tropes, and recurring turns-of-phrase. The younger of my mind-sparks added that, in addition to taking up time that an writer might otherwise spend at the keyboard, the discovery of a new fact will often lead to a quest for fresh forms of expression.

So, to quote the immortal words of David Crowther, you pays your money and you takes your choice. You can write quickly, or you can say something new, but you can’t do both.

Bruce Ivar Gudmundsson, “The Price of Speed”, Extra Muros, 2024-05-21.

August 26, 2024

The craft of the historian, then and now

At Extra Muros, Bruce Ivar Gudmundsson contrasts the way historians used to research and write their books with the much more convenient, yet still imperfect methods of modern historians:

In days of yore, when visiting an archive required long journeys by sea, or, at the very least, a tiring trek o’er moor and mountain, considerate historians stuffed their works, with extensive excerpts from primary sources.1 Later, when trains, planes, and automobiles made it easier for people to visit the places where original documents could be found, these quotations shrank, eventually to the point where the word “citation”, which had once described the products of scholarly stenography, came to designate the label that enabled readers to locate the one-of-a-kind text in question.

No doubt, this development saved many trees from the woodman’s axe. At the same time, however, it changed the role played by historians. Rather than showcasing selections from the correspondence of old-timey movers and shakers, Clio’s children devoted most of the ink that they spilled to the explanation of texts that, despite the blessings bestowed by coal and petroleum, most readers would not be able to read.

Many a noble soul resisted the temptation to sacrifice verbatim reproduction on the altar of erudite interpretation. Realizing that readers might prefer a faithful facsimile of the real McCoy to a ponderous paraphrase, these saints of the scriptorium prepared primary sources for the press. However, rather rewarding these benefactors of the historically curious with condign praise, the denizens of the faculty lounge often dismissed them as “editors” and, in moments of especial cruelty, “antiquarians”.

In the fullness of time, the convenience provided by recent interpretations led many historians to prefer them to the relics of bygone bureaucracies. After all, reading a fresh-smelling, neatly-bound, clearly-printed, recently-written book asks less of a scholar than the deciphering of unfamiliar turns-of-phrase scribbled on the dusty, mite-bitten contents of cardboard boxes. Moreover, while the reader of a scholarly monograph often enjoys a wide choice of restaurants and coffee shops, and, at the very least, the delights of his own kitchen, the archival archaeologist must often make do with the decidedly institutional offerings of a ground-floor cafeteria.

Ostentatious reliance on recent interpretations also enables a scholar to exhibit his collegiality. “See”, the favorable footnote screams, “someone noticed your work and, marvelous to say, made use of it”. Conversely, failure to cite the work of a peer, let alone a scholar of superior standing, signals a degree of nonchalance bordering on contempt. “I am fully aware”, it says to the author of the unreferenced work, “that you poured your heart and soul, as well as a dozen years of your life, into your study, but I could not be bothered to type out its title, let alone turn a page to discover its date of publication”.

Finally, the making of new monographs out of the pieces of slightly older ones honors the founding fable of the research university, the myth of scholarly progress. The monograph still warm from the press, we presume, offers more in the way of insight and understanding than one that has been sitting on the shelf for decades. (If you wish to drive a dagger into the heart of an older academic, describe one of his earlier works, especially one that once made a splash in the kiddie-pool of his subfield, as “somewhat dated”.)2

Prejudice in favor of up-to-date interpretations creates a paradox. Historians, who exist to bring the past to life, favor interpretations created on the eve of now. The speakers for the dead (hat tip to Orson Scott Card) limit themselves to the thoughts of the living.

1. For a brief, and delightfully documented, description of the work of the paragon of this approach to the writing of history, Angelo Fabroni (1732-1803), see Anthony Grafton The Footnote: A Curious History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997) pages 82 and 83.

2. Ask me how I know!

July 17, 2024

QotD: “Orwellian”

All writers enjoying respect and popularity in their lifetimes entertain the hope that their work will outlive them. The true mark of a writer’s enduring influence is the adjectification of his (sorry, but it usually is “his”) name. An especially jolly Christmas scene is said to be “Dickensian”. A cryptically written story is “Hemingwayesque”. A corrupted legal process gives rise to a “Kafkaesque” nightmare for the falsely accused. A ruthless politician takes a “Machiavellian” approach to besting his rival.

But the greatest of these is “Orwellian”. This is a modifier that The New York Times has declared “the most widely used adjective derived from the name of a modern writer … It’s more common than ‘Kafkaesque’, ‘Hemingwayesque’ and ‘Dickensian’ put together. It even noses out the rival political reproach ‘Machiavellian’, which had a 500-year head start.”

Orwell changed the way we think about the world. For most of us, the word Orwellian is synonymous with either totalitarianism itself or the mindset that is eager to employ totalitarian methods — notably the bowdlerization or suppression of speech and freedoms — as a hedge against popular challenge to a politically correct vision of society dictated by a small cadre of elites.

Indeed, it was thanks to Orwell’s books — forbidden, acquired by stealth and owned at peril — that many freedom fighters suffering under repressive regimes, found the inspiration to carry on their struggle. In his memoir, Adiós Havana, for example, Cuban dissident Andrew J. Memoir wrote, “Books such as … George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984 became clandestine bestsellers, for they depicted in minute detail the communist methodology of taking over a nation. These […] books did more to open the eyes of the blind, including mine, than any other form of expression.”

Barbara Kay, “The way they teach Orwell in Canada is Orwellian”, The Post Millennial, 2019-11-29.