For as long as I can remember, readers have been trained to associate literary archaism with the stuffy and Victorian. Shielded thus, they may not realize that they are learning to avoid a whole dimension of poetry and play in language. Poets, and all other imaginative writers, have been consciously employing archaisms in English, and I should think all other languages, going back at least to Hesiod and Homer. The King James Version was loaded with archaisms, even for its day; Shakespeare uses them not only evocatively in his Histories, but everywhere for colour, and in juxtaposition with his neologisms to increase the shock.

In fairy tales, this “once upon a time” has always delighted children. Novelists, and especially historical novelists, need archaic means to apprise readers of location, in their passage-making through time. Archaisms may paradoxically subvert anachronism, by constantly yet subtly reminding the reader that he is a long way from home.

Get over this adolescent prejudice against archaism, and an ocean of literary experience opens to you. Among other things, you will learn to distinguish one kind of archaism from another, as one kind of sea from another should be recognized by a yachtsman.

But more: a particular style of language is among the means by which an accomplished novelist breaks the reader in. There are many other ways: for instance by showering us with proper nouns through the opening pages, to slow us down, and make us work on the family trees, or mentally squint over local geography. I would almost say that the first thirty pages of any good novel will be devoted to shaking off unwanted readers; or if they continue, beating them into shape. We are on a voyage, and the sooner the passengers get their sea legs, the better life will be all round.

David Warren, “Kristin Lavransdatter”, Essays in Idleness, 2019-03-21.

August 9, 2022

QotD: Fusty old literary archaism

August 8, 2022

Boring British politicians

Katherine Bayford compares the last set of cabinet ministers appointed by lame duck PM Boris Johnson with some of the Parliamentarians of the 20th century … and it’s difficult not to feel nostalgic for a past Golden Age at Westminster:

Prime Minister Boris Johnson at his first Cabinet meeting in Downing Street, 25 July 2019.

Official photograph via Wikimedia Commons.

One of Boris Johnson’s final, whimpering acts of power in his premiership was to appoint a new cabinet. Fatally wounded by a team of ministers made up of those with little charm, intelligence or experience, who was actually left for Boris to replace them with?

A veritable who’s-that of the worst unknowns that can be found down the side of parliamentary benches was swiftly conscripted in. I tell a lie — Johnny Mercer MP achieved mild public recognition for defending elderly soldiers accused of war crimes and getting very angry at certain risqué insinuations made in the comments section of the Plymouth Herald.

[…]

There is nothing unusual about this class of minister, however. They are representative figures: dim, without verbal sparkle, frequently light on narrow policy insights and wider understandings of social and economic history. The median British politician has been like this for decades now. Tony Blair would bemoan the shoddy material he had to work with at every reshuffle, and David Cameron likewise found himself struggling for a front bench neither too hateful nor too stupid. The difference in political acumen and sophistication from the most forgotten of ministerial interviews from fifty years ago reveal a steep decline in both the eloquence and elegance of our politicians.

Perhaps the 20th century spoiled the voting public. Pick any decade and you will discover frontline politicians with vast hinterlands. Harold Macmillan recited Aeschylus — in the original Greek — whilst lying shot in the trenches. Enoch Powell rose from private to brigadier during the Second World War, after becoming the youngest professor in the empire. When Winston Churchill was attempting to stay solvent in the face of decades worth of excess, he maintained financial buoyancy by being the highest-paid journalist in the world. Publishers adored him. He could be trusted to write a million-word definitive biography of his relative, the first Duke of Marlborough. Roy Jenkins would in turn distinguish himself as a biographer of Churchill — as well as Gladstone, and the Chancellors of the Exchequer at large. Second-hand embarrassment is the only proper response when comparing such authorial endeavours to Boris Johnson’s biography of Churchill.

It’s not a matter of our politicians not being able to write anymore. Compared to the recent past they can barely speak. Political debates have succumbed to an entropic, deadening mediocrity. Recent discourse between a patronising, bland Sunak and a po-faced, blank Truss was not a nadir: it was standard fare.

Look upon this 1970 debate between Jenkins and Powell. Both men hold articulate and intelligent positions, arguing intricately and considerately, with a commitment to truth rather than point-scoring. They agree where relevant and have an ability to articulate clearly and fluently. Half a century on, political debate of such quality seems unrealisable. When watching vintage ministerial debates, the viewer is struck by the level of knowledge and attention that the speakers assumed their audience would possess, whether on the finer points of tackling inflation or whether IRA bombers deserved to the death penalty.

The slightest glance at cabinets fifty years ago demonstrates a far higher set of standards and abilities than those found today. Harold Wilson — always keen to consolidate as much power as possible — nevertheless packed his cabinet with the best and brightest, even if he kept them in positions in which they wouldn’t be able to outshine him. Wilson himself was a subtle and clever debater, not above using cheap PR tricks (such as his much-perfected pipe smoking) but always as a tool to realise his political vision.

Mediocrity requires mediocrity in order to survive. When judged against excellence — or even simple competence — the insufficiencies of today’s politician become intolerable. It is this which leads the public to distrust politicians more than their policy choices.

July 31, 2022

American publishing has a race problem, but it has an even bigger gender problem

In the latest edition of the SHuSH newsletter, Kenneth Whyte considers a recent online brouhaha featuring novelist Joyce Carol Oates and notes that while she was being dragged by the usual online mob for her perceived defence of “white” authors, an even bigger problem for the ever-diminishing number of “big” publishing houses is their gender balance:

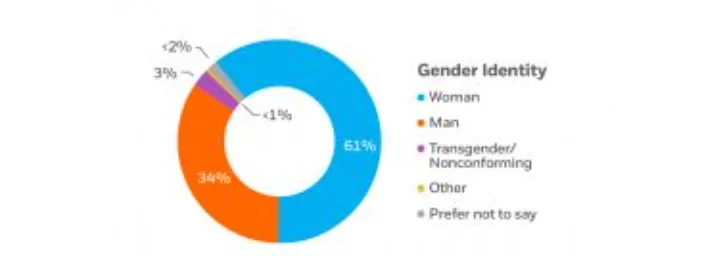

Publishing also has a gender problem. Only 34 per cent of the Penguin Random House workforce is male.

When you eliminate the warehouse staff, that figure drops to 26 per cent.

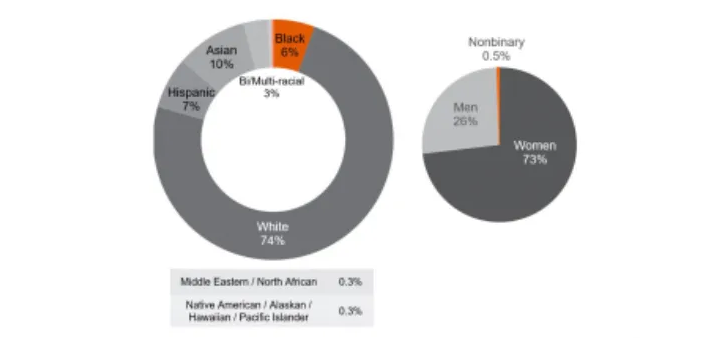

A Lee & Low survey from 2019 put the male component of the US publishing workforce at 24 per cent and a Canadian survey (referenced in SHuSH 90) found our publishing sector is 74 per cent women and 18 per cent men. Oates’ critics, many of them women, skated over this part of the equation.

That’s not unusual. Most people in publishing skate over this part of the equation. A few years back, when it was revealed that men are just 20 per cent of the fiction reading public, the question arose, might that have something to do with the lack of men acquiring and marketing books. Hardly anyone in publishing thought so. As I noted at the time, a Random House spokesperson said the gender composition of the firm was “not an issue of concern or even much contemplation for us”. And the head of Columbia U’s publishing program asserted that “great literature transcends gender in terms of editors”. A UK literary agent attributed the gender disparity in fiction to merit: some men, she said, “just aren’t very good”.

I spoke to several agents this week to see if the agent mentioned by Oates was an anomaly. What I heard suggests not. My agents were not surprised by the assessment of the anonymous agent. One just shrugged, as in, “what’s new?”

Whether the comments following the Oates’ tweet are valid — “it’s about time”, or “welcome to the oppressed, now you know what it feels like” — I’m probably not qualified to say. The real issue, which seems to be missed in this conversation, is that work is very often not judged by its quality but by who the author is and what the author represents. (Not a wholly new phenomenon in the world.) It is heartbreaking to see work of real talent, maybe even genius, being rejected by publishers (and I do see this in action) in favour of an author who has the right name and biometrics.

Not all of my agents agreed with Oates’ anonymous agent. One said, “It’s equally hard to sell everybody in this market. I’ve got white authors, black authors, brown authors. It’s hard to get a good deal anywhere. The consolidation in the industry is real: there are fewer editors to pitch books to than there used to be.”

This agent admits that the trend is now toward loading up on BIPOC authors but believes that will blow itself out, as all trends do, and the publishing houses will all chase after the next shiney thing. As for the situation inside publishing houses, “it’s been tough for guys as long as I’ve been in the business. Talk to the white male editors who sit on editorial boards at publishing house and they’ll tell you, it’s tough, there’s a lot of pushback from the other voices around the table.”

This agent also noted that the agency world is starting to break down along gender lines. Not surprisingly, literary agents are overwhelmingly white women. Increasingly, they are representing only women.

July 25, 2022

Rowan Atkinson & Hugh Laurie – Shakespeare and Hamlet (1989)

Nathaniel Brechtmann

Published 1 Sep 2011A sketch called “A Small Rewrite”, performed by Hugh Laurie (aka House) as Shakespeare and Rowan Atkinson (aka Mr Bean) as the editor.

June 27, 2022

QotD: Perfectionism

Perfectionism should be classified as a disability.

It has blighted more lives than autism, destroyed more potential work than brain damage, stopped more achievement than mis-education. It can devour entire civilizations, and arguably has. […] If you’re an artist or even just a “creator” or worker: a writer, an artist, a programmer, a cook, holy heck, even a house cleaner, you know exactly what I’m talking about.

There’s this odd tendency to be more dissatisfied with our work the better we do and then to decide not to do things because, what the heck, it will never be good enough.

The way it blights lives is … interesting. As in I’ve seen perfectionists utterly ruin themselves by doing nothing. Oh, you want to write/create/climb your work ladder? But you look at your work and you know you’re not good enough because you can see flaws, so why even try. And then you do nothing. And then … and then you’re 65 and you’ve done nothing and achieved nothing in your life, and it’s a miracle if you came close to supporting yourself. (And the only reason you’ve done so is because you did some job you considered was menial and didn’t matter, so your perfectionism didn’t infect THAT.)

If you’re a true perfectionist, you also never had any relationships. Because even though you’re far from the ideal mate, you judge every potential by tagging up defects. If you can’t have perfection, why bother.

The very smart are extremely susceptible to this, but everyone can fall into the trap. If you care or know enough about any field, the flaws in your own (and others) work will stand out glaringly and in relief and then you can’t do ANYTHING.

Of course, the more you practice and know the more flaws you see. And it eventually shuts you down. I catch myself in this trap frequently to the point of being amazed when semi-pro anthos buy my work, because I’m sure it’s the worst thing ever written. And I can shut myself down for years. (I’m not alone, I know you know other writers with this problem.)

Sarah Hoyt, “The Flaw in Flawless”, According to Hoyt, 2019-02-27.

May 13, 2022

QotD: Youthful (writing) indiscretions

To reach middle age, one must first pass through an earlier stage of simultaneously knowing very little about the world while believing oneself to understand it completely. Youthful folly is particularly unfortunate in budding writers, who inevitably commit their stupidity to the page. If they write for publication — rather than privately composing the worst novel ever written in the English language, as I did at that age — their silliness will linger for posterity to sample.

Megan McArdle, “In attacking Neomi Rao, Democrats are arguing against progress — in more ways than one”, Santa Cruz Sentinal, 2019-02-06.

May 8, 2022

April 12, 2022

QotD: Writers are like otters

Tor editor Teresa Nielsen Hayden had a wonderful rant some years back. She had been talking to an animal trainer, who explained to her why otters were untrainable. Other animals, it seemed, when given their food reward or whatever by their human handler, would seem to think, “Great, he liked it! I’ll do that again!” Otters, by contrast, would seem to think, “Great, he liked it! Now I’ll do something else that’s even cooler!” Writers, Teresa concluded in a moment of Zen enlightenment, were otters. At least from an editor’s point of view.

When I boot up a new book in my brain, I am not greatly interested in what has and hasn’t won awards. I want to write something else that’s even cooler.

Lois McMaster Bujold, interview at Blogcritics, 2005-05-24.

April 5, 2022

QotD: The “rules” of bad writing

Another common habit of the bad writer is to use five paragraphs when one paragraph will do the trick. One of the first rules they used to teach children about writing is the rule of women’s swimsuits. Good writing is like a woman’s swimsuit, in that it is big enough to cover the important parts, but small enough to make things interesting. This is a rule that applies to all writing and one bad writers tend to violate. They will belabor a point with unnecessary examples or unnecessary explication.

Bad writers are also prone to logical fallacies and misnomers. There’s really no excuse for this, as there are lists of common logical fallacies and, of course, searchable on-line dictionaries in every language. In casual writing, like blogging or internet commentary, this is tolerable. When it shows up in a professional publication, it suggest the writer and the editor are not good at their jobs. A brilliantly worded comparison between two unrelated things is still a false comparison. It suggests dishonesty on the part of the writer.

Certain words seem to be popular with bad writers. The word “dialectic” has become an acid test for sloppy reasoning and bad writing. The word “elide” is another one that is popular with bad writers for some reason. “Epistemology” is another example, popular with the legacy conservative writers. Bad writers seem to think cool sounding words or complex grammar will make their ideas cleverer. Orwell’s second rule is “Never use a long word where a short one will do.” It’s commonly abused by bad writers.

Finally, another common feature of bad writing is the disconnect between the seriousness of subject and how the writer approaches the subject. Bad writers, like Jonah Goldberg, write about serious topics, using pop culture references and vaudeville jokes. On the other hand, feminists write about petty nonsense as if the fate of the world hinges on their opinion. The tone should always match the subject. Bad writers never respect the subject they are addressing or their reader’s interest in the subject.

The Z Man, “How To Be A Bad Writer”, The Z Blog, 2019-03-03.

March 30, 2022

QotD: Orwell on political writing

A scrupulous writer, in every sentence that he writes, will ask himself at least four questions, thus: What am I trying to say? What words will express it? What image or idiom will make it clearer? Is this image fresh enough to have an effect? And he will probably ask himself two more: Could I put it more shortly? Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly? But you are not obliged to go to all this trouble. You can shirk it by simply throwing your mind open and letting the ready-made phrases come crowding in. They will construct your sentences for you — even think your thoughts for you, to a certain extent — and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself.

George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language”, 1946.

March 24, 2022

QotD: Tolkien’s wartime experiences and The Lord of the Rings

… there’s more to Tolkien than nostalgic medievalism. The Lord of the Rings is a war book, stamped with an experience of suffering that his modern-day critics can scarcely imagine. In his splendid book Tolkien and the Great War, John Garth opens with a rugby match between the Old Edwardians and the school’s first fifteen, played in December 1913. Tolkien captained the old boys’ team that day. Within five years, four of his teammates had been killed and four more badly wounded. The sense of loss haunted him for the rest of his life. “To be caught in youth by 1914 was no less hideous an experience than to be involved in 1939 and the following years,” he wrote in the second edition of The Lord of the Rings. “By 1918, all but one of my close friends were dead.”

Tolkien arrived on the Western Front in June 1916 as a signals officer in the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers, and experienced the agony of the Somme at first hand. In just three and a half months, his battalion lost 600 men. Yet it was now, amid the horror of the trenches, that he began work on his great cycle of Middle-earth stories. As he later told his son Christopher, his first stories were written “in grimy canteens, at lectures in cold fogs, in huts full of blasphemy and smut, or by candlelight in bell-tents, even some down in dugouts under shell fire”.

But he never saw his work as pure escapism. Quite the opposite. He had begun writing, he explained, “to express [my] feeling about good, evil, fair, foul in some way: to rationalise it, and prevent it just festering”. More than ever, he believed that myth and fantasy offered the only salvation from the corruption of industrial society. And far from shaking his faith, the slaughter on the Somme only strengthened his belief that to make sense of this broken, bleeding world, he must look back to the great legends of the North.

Yet The Lord of the Rings is not just a war book. There’s yet another layer, because it’s also very clearly an anti-modern, anti-industrial book, shaped by Tolkien’s memories of Edwardian Birmingham, with its forges, factories and chimneys. As a disciple of the Victorian medievalists, he was always bound to loathe modern industry, since opposition to the machine age came as part of the package. But his antipathy to all things mechanical was all the more intense because he identified them — understandably enough — with killing.

And although Tolkien objected when reviewers drew parallels between the events of The Lord of the Rings and the course of the Second World War, he often did the same himself. Again and again he told his son Christopher that by embracing industrialised warfare, the Allies had chosen the path of evil. “We are attempting to conquer Sauron with the Ring,” he wrote in May 1944. “But the penalty is, as you will know, to breed new Saurons, and slowly turn Men and Elves into Orcs.” Even as the end of the war approached, Tolkien’s mood remained bleak. This, he wrote sadly, had been, “the first War of the Machines … leaving, alas, everyone the poorer, many bereaved or maimed and millions dead, and only one thing triumphant: the Machines”.

“Trivial”, then? Clearly not. Tolkien was at once a war writer and an ecological writer; a product of High Victorianism and also a distant relative of the modernist writers who, like him, were trying to make sense of the shattered world of the Twenties and Thirties. But he wasn’t just a man of his time; he remains a guide for our own.

Dominic Sandbrook, “This is Tolkien’s world”, UnHerd, 2021-12-09.

March 17, 2022

QotD: The curse of creativity

Creative genius often seems to be ladled out to those who are manifestly unworthy of it. Indeed, artistic genius has been so frequently bound up with vanity, neurosis, lust, and the rest of the Seven Deadly Sins that it might be considered more of a curse than a blessing. The literature of the West is replete with stories of geniuses whose hubris brings about tragic consequences, from Oedipus Rex to Doctor Faustus to Frankenstein and beyond. Whether in art, science, or politics, creative genius is a form of power, and power, as we all know, corrupts.

Gregory Wolfe, “In God’s Image: The virtue of creativity”, National Review, 2005-05-27.

March 7, 2022

QotD: Historical fiction and fantasy works usually leave out the vast majority of the people who did all the work

… there is a tendency when popular culture represents the past to erase not merely the farmers, but most of the commons generally. Castles seem to be filled with a few servants, a whole bunch of knights and lords and perhaps, if we are lucky, a single blacksmith that somehow makes all of their tools.

But the actual human landscape of the pre-modern period was defined – in agrarian societies, at least – by vast numbers of farms and farmers. Their work proceeded on this cyclical basis, from plowing to sowing to weeding to harvesting and threshing to storage and then back again. Religious observances and social festivals were in turn organized around that calendar (it is not an accident how many Holy Days and big festivals seem to cluster around the harvest season in late Autumn/early Winter, or in Spring). The uneven labor demands of this cycle (intense in plowing and reaping, but easier in between) in turn also provided for the background hum of much early urban life, where the “cities” were for the most part just large towns surrounded by farmland (where often the folks living in the cities might work farmland just outside of the gates). People looked forward to festivals and events organized along the agricultural calendar, to the opportunities a good harvest might provide them to do things like get married or expand their farms. The human drama that defines our lives was no less real for the men and women who toiled in the fields or the farmhouses.

And of course all of this activity was necessary to support literally any other kind of activity.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part III: Actually Farming”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-08-06.

January 5, 2022

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

In The Critic, David Engels outlines the early life and career of J.R.R. Tolkien:

The biography of the British writer and philologist John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (1892-1973) is quickly summarised and, despite a few unusual cornerstones such as his early childhood in South Africa, the tragic death of his parents and the highly romantic love for his later wife Edith, not very spectacular. An existence confined entirely to the British Isles except for a few forays into the continent; a military service in the Great War only moderately traumatic compared to other fates; an honourable but hardly groundbreaking academic career; a life as father of a family that knew the most varied but hardly extraordinary fortunes.

Not really the stuff of legends — except for the global success of The Lord of the Rings, which arrived too late to set Tolkien’s existence on a different course. The (deeply unsatisfying) 2019 film adaptation of Tolkien’s youth attempts to surround him with the aura of a scholarly genius and war hero, and to explain his literary work biographically — but this reductionist attempt rather hinders the understanding of his oeuvre. Tolkien’s works are not exceptional because his life was: on the contrary, their exceptionality only gains its full significance when they are understood against the background of an altogether quite normal existence.

Of course, with such an undramatic approach, it is tempting to associate Tolkien’s enormous mythopoeic activity with the catchword “escapism”, and to reduce it once again to his biography, albeit this time not as a correspondence but as a compensation. This, too, misses the point — all the more so because Tolkien’s earliest literary activity goes far back into his teenage years: his work is not a reaction to his life, but rather the two grew in union, not unlike the mythical trees Telperion and Laurelin. Indeed, one might even regard Tolkien’s rather ordinary academic and family life as a consequence of his consuming, lifelong work on myth rather than the other way around. But what was Tolkien’s intention — and what can we learn from him?

In the beginning, there was disappointment. The Anglo-Saxon world, unlike France or Germany, has scarcely left any traces of an indigenous myth tradition; even the saga of King Arthur belongs to the pre-Anglo-Saxon, Celtic tradition. The Norman Conquest destroyed the entire Anglo-Saxon legend tradition, apart from a few nursery rhymes and place names and a very brittle literary corpus.

As an ardent lover of the Northwest of the Old World, the young Tolkien felt cut off from his own heritage and enthusiastically took up Indo-European linguistics as a technique for reconstructing the historical and mythical tradition of times long past. He set about, partly in play, partly in earnest, creatively deciphering and reconstructing the hitherto misunderstood evidence of England’s dark centuries. In the process, the boundary between etymology and mythopoetics quickly blurred, as Tolkien enriched the hypothetical material obtained by merging it with the archetypal content of the other legends of the ancient world. He created a mythical tradition that took on a character of its own.

But it would be wrong to interpret this legendarium, which was born out of linguistics but soon took on increasingly literary features, as a mere poetic game. Especially in the initial phase of his attempts, Tolkien endeavoured to introduce the increasingly coherent legends and sagas, which are known to the general public mainly through the posthumous Silmarillion and the publishing activities of his son Christopher, by use of a wide variety of framework plots, some of which have an old Anglo-Saxon character and some which are set in modern times. The leitmotif was the dream of the great wave that swallowed up a green island, which later became the seed of the “Fall of Númenor”; an image that haunted Tolkien himself often enough in his sleep and led him to state that those images, recorded partly in dreams and partly in a half-awake state, were not to be regarded as mere fiction, but rather as access to something true and permanent, which he fleshed out in various literary ways, but whose core consistently bore the character of a vision.

November 23, 2021

Tucker Carlson’s new book The Long Slide

Wilfred M. McClay reviews Carlson’s collected essays for First Things:

Tucker Carlson has become such a fixture in the world of cable-television news that it’s easy to forget he began his journalistic career as a writer. And a very good one at that, as this wide-ranging and immensely entertaining selection of essays from the past three decades serves to demonstrate. Carlson’s easygoing, witty, and compulsively readable prose has appeared everywhere from The Weekly Standard (where he was on staff during the nineties) to the New York Times, the Spectator, Forbes, New Republic, Talk, GQ, Esquire, and Politico, which in January 2016 published Carlson’s astonishing and prophetic article titled “Donald Trump is Shocking, Vulgar, and Right”. That essay has been preserved for posterity in these pages, along with twenty-two other pieces, plus a bombshell of an introduction written expressly for the occasion. More of that in a moment.

The first response of many of today’s readers, particularly those who don’t like the tenor of Carlson’s generally right-populist politics or the preppy swagger and bubbly humor of his TV persona, will be to dismiss The Long Slide as an effort to cash in on the author’s current notoriety by recycling old material to make a buck. That was my assumption when I first opened this collection. But the book has an underlying unity, and a serious message. It evokes a bygone age, an era of magazine and newspaper journalism that seems golden in retrospect, and is now so completely gone that one must strain to imagine that it ever existed at all. The simple fact is that almost none of these essays could be published today, certainly not in the same venues: They are full of language and imagery and a certain brisk cheerfulness toward their subject matter that could not possibly pass muster with the Twittering mob of humorless and ignorant moralists who dictate the editorial policies of today’s elite journalism.

Carlson’s writing style reflects the influence of the New Journalists such as Tom Wolfe and Hunter Thompson, who brought a jaunty, whiz-bang you-are-there narrative verve and high-spirited drama to the task of telling vividly detailed stories about unusual people and places, generally relating them in the first person. Carlson’s prose is not as spectacular as Wolfe’s or as thrillingly unhinged as Thompson’s. But it has its own virtues, being crystal clear, conversational, direct, and vigorous, never sending a lardy adjective to do the work of a well-chosen image, and never using gimmicky wild punctuation or stretched-out words to fortify a point. He’s a blue-blazer and button-down-collar guy, not a compulsive wearer of prim white suits or a wigged-out drug gourmand wearing a bucket hat and aviator glasses. But many of Carlson’s writings give the same sense of reporting as an unfolding adventure, a traveling road show revolving around the reactions and experiences of the author himself.

Carlson usually shows a certain fundamental affection for the people he writes about, even if he also ribs or mocks them in some ways. In particular, there is none of that ugly contempt for the “booboisie” and ordinary Americans that one finds, for example, in the pages of H.L. Mencken, and in a great deal of prestige journalism. Instead, he reserves his contempt for the well-heeled know-it-alls who genuinely deserve it. In that sense, the Carlson of these essays does not seem very different from the Carlson of today. He always has been a bit of a traitor to his class, and commendably so.