seangabb

Published 12 Sept 2024Part seven in a series on Everyday Life in the Roman Empire, this lecture discusses demography and life chances during the Imperial period. Here is what it covers:

Introduction – 00:00:00

Our Statistical Civilisation – 00:00:24

Ancient “Statistics” – 00:08:05

How Many Roman Citizens? – 00:18:04

Population of the Empire – 00:21:36

City Populations – 00:27:45

Average Incomes – 00:36:27

Life Expectancy – 00:35:37

Country Life – 00:52:06

Population of Rome – 00:54:39

Feeding Rome – 00:57:40

Roman Water Supply – 01:00:44

Bathing and Sanitation – 01:04:16

Hygienic Value – 01:04:16

Bibliography – 01:06:17

(more…)

March 20, 2025

Everyday Life in the Roman Empire – Demography, Income, Life Expectancy

February 15, 2025

QotD: The absurdly high early expectations for genetic research

For decades, people talked about “the gene for height”, “the gene for intelligence”, etc. Was the gene for intelligence on chromosome 6? Was it on the X chromosome? What happens if your baby doesn’t have the gene for intelligence? Can they still succeed?

Meanwhile, the responsible experts were saying traits might be determined by a two-digit number of genes. Human Genome Project leader Francis Collins estimated that there were “about twelve genes” for diabetes, and “all of them will be discovered in the next two years”. Quanta Magazine reminds us of a 1999 study which claimed that “perhaps more than fifteen genes” might contribute to autism. By the early 2000s, the American Psychological Association was a little more cautious, was saying intelligence might be linked to “dozens – if not hundreds” of genes.

The most recent estimate for how many genes are involved in complex traits like height or intelligence is approximately “all of them” – by the latest count, about twenty thousand. From this side of the veil, it all seems so obvious. It’s hard to remember back a mere twenty or thirty years ago, when people earnestly awaited “the gene for depression”. It’s hard to remember the studies powered to find genes that increased height by an inch or two. It’s hard to remember all the crappy p-hacked results that okay, we found the gene for extraversion, here it is! It’s hard to remember all the editorials in The Guardian about how since nobody had found the gene for IQ yet, genes don’t matter, science is fake, and Galileo was a witch.

And even remembering those times, they seem incomprehensible. Like, really? Only a few visionaries considered the hypothesis that the most complex and subtle of human traits might depend on more than one protein? Only the boldest revolutionaries dared to ask whether maybe cystic fibrosis was not the best model for the entirety of human experience?

Scott Alexander, “The Omnigenic Model As Metaphor For Life”, Slate Star Codex, 2018-09-13.

February 5, 2025

QotD: Economies and disasters

Here’s a question: Are natural or manmade disasters good for the economy? Dr. Larry Summers, top economic adviser to President Obama, said about the Kobe, Japan, earthquake: “(The disaster) may lead to some temporary increments ironically to GDP as a process of rebuilding takes place. In the wake of the earlier Kobe earthquake Japan actually gained some economic strength.” After devastating Floridian hurricanes, it’s not uncommon to read newspaper headlines such as “Storms create lucrative times”, or “Economic growth from hurricanes could outweigh costs”, or “It’s a perverse thing … there’s real pain, but from an economic point of view, it is a plus”. Then there’s Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman who wrote in his New York Times column “After the Horror”, after the 9/11 attack, “Ghastly as it may seem to say this, the terror attack — like the original day of infamy, which brought an end to the Great Depression — could do some economic good”. He went on to explain that rebuilding the destruction would stimulate the economy through business investment and job creation.

One would never hear my colleagues in George Mason University’s economics department spouting such insanities. Just ask yourself whether the Japanese economy would have faced even greater opportunities for economic growth had the earthquake also struck Tokyo, Hiroshima, Yokohama and other major cities? Would the 9/11 terrorists have made a greater contribution to our economy had they also destroyed lives and buildings in Chicago, St. Louis, Los Angeles and Atlanta? The belief that a society benefits from destruction is sheer lunacy.

French economist Frederic Bastiat (1801-1850) explained it in his pamphlet “What is Seen and What is Not Seen”. He said, “There is only one difference between a bad economist and a good one: the bad economist confines himself to the visible effect; the good economist takes into account both the effect that can be seen and those effects that must be foreseen”. That’s why my George Mason University colleagues are good economists.

Walter E. Williams, “Economics Reality”, Townhall.com, 2020-02-04.

February 1, 2025

QotD: In a centrally planned economy, all that matters is meeting or exceeding the Gross Output Target

The mobbed-up oligarchs currently running Russia, for instance, were almost all members of an informal class whose name I forget, which translates as “brokers” or “wheeler-dealers” or something. They learned how best to manipulate the Soviet system of “gross output targets”. Back when he was funny, P.J. O’Rourke had a great bit about this in Eat the Rich, a book I still recommend.

When told to produce 10,000 shoes, the shoe factory manager made 10,000 baby shoes, all left feet, because that was easiest to do with the material on hand — he didn’t have to retool, or go through nearly as many procurement processes, and whatever was left over could be forwarded to the “broker”, who’d make deals with other factory managers for useful stuff. When Comrade Commissar came around and saw that the proles still didn’t have any shoes, he ordered the factory manager to make 10,000 pairs of shoes … so the factory manager cranked out 20,000 baby shoes, all left feet, tied them together, and boom. When Comrade Commissar switched it up and ordered him to make 10,000 pounds of shoes, the factory manager cranked out one enormous pair of concrete sneakers …

So long as Comrade Commissar doesn’t rat him out to the NKVD — and why would he? he’s been cut in for 10% — nobody will ever be the wiser, because on the spreadsheet, the factory manager not just hit, but wildly exceeded, the Gross Output Target. That nobody in Krasnoyarsk Prefecture actually has any shoes is irrelevant.

Severian, “The Finger is Not the Moon”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-09-14.

January 17, 2025

“… most of them can do simple low-IQ jobs like manual labor, basic retail, or writing for the New York Times“

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander discusses the highly controversial national IQ estimates of Richard Lynn … I’m sure I don’t need to spell out exactly why they were (and continue to be) controversial:

Lynn’s national IQ estimates (source)

Richard Lynn was a scientist who infamously tried to estimate the average IQ of every country. Typical of his results is this paper, which ranged from 60 (Malawi) to 108 (Singapore).

People obviously objected to this, and Lynn spent his life embroiled in controversy, with activists constantly trying to get him canceled/fired and his papers retracted/condemned. His opponents pointed out both his personal racist opinions/activities and his somewhat opportunistic methodology. Nobody does high-quality IQ tests on the entire population of Malawi; to get his numbers, Lynn would often find some IQ-ish test given to some unrepresentative sample of some group related to Malawians and try his best to extrapolate from there. How well this worked remains hotly debated; the latest volley is Aporia‘s Are Richard Lynn’s National IQ Estimates Flawed? (they say no).

I’ve followed the technical/methodological debate for a while, but I think the strongest emotions here come from two deeper worries people have about the data:

First, isn’t it horribly racist to say that people in sub-Saharan African countries have IQs that would qualify as an intellectual disability anywhere else?

Second, isn’t it preposterous and against common sense to compare sub-Saharan Africans to the intellectually disabled? You can talk to a Malawian person, and talk to a person with Down’s Syndrome, and the former is obviously much brighter and more functional than the latter. Doesn’t that mean that the estimates have to be wrong?

But both of these have simple answers, which IMHO defuse the worrying nature of Lynn’s results. These answers aren’t original to me, but as far as I know, nobody has put them together in one place before. Going over each in turn:

1: Isn’t It Super-Racist To Say That People In Sub-Saharan African Countries Have IQs Equivalent To Intellectually Disabled People?

No. In fact, it would be super-racist not to say this! We shouldn’t conflate advocacy with science. But if we did, Lynn’s position would make better anti-racist advocacy than his detractors’.

The “racist” position is that all IQ differences between groups are genetic. The “anti-racist” position is that they’re a product of environment — things like nutrition, health care, and education.

We know that in the US, where we do give people good IQ tests, whites average IQ 100 and blacks average IQ 85.

If IQ was 100% genetic, we should expect Africans to have an IQ of 85, since American and African blacks have similar genes. This isn’t exactly right — US blacks have some intermixing with whites, and only some of Africa’s staggering diversity reached the US — but it’s close enough.

December 1, 2024

QotD: Recording and codifying the land that William conquered

I hesitate to recommend academic books to anyone, but I’ll make an exception for James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State. Subtitled “how certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed”, it’s the best long-form exposition I know of, that explains how process and outcome first deform, then negate each other.

[…]

In brief, Scott argues that the process of making a society “legible” to government officials obscures social reality, to the point where the government’s maps and charts and graphs take on a life of their own. It’s recursive, such that those well-intentioned schemes end up first measuring, then manipulating, the wrong thing in the wrong way, to the point that the social “problem” the process was supposed to address drops out entirely — all you have, at the end, is powerpoint girls critiquing spreadsheet boys because their spreadsheets don’t have enough animation, and vice versa.

Scott doesn’t use the Domesday Book as an example (IIRC from a graduate school class 20-odd years ago, anyway), but it’s one we’re probably all familiar with. The first thing William the Conqueror needed to know is: what, exactly, have I conquered? So he sent out the high-medieval version of spreadsheet boys to take a comprehensive survey of the kingdom. Turns out the Duke of Earl’s demense runs from this creek to that rock. He has five underlings, and their domains run from etc.

The point of all this, of course, was so that Billy C. could call the Duke of Earl on the carpet, point to the spreadsheet, and say “You owe me a cow, three chickens, and two months in the saddle as back taxes.” It worked great, except when — as, it seems, is inevitable — the high-medieval equivalent of the spreadsheet boys did the high-medieval version of “ctrl-c”; just copying and pasting the information over. Eventually the tax situation got way out of whack, as it did for most every pre-modern government running a similar system — one of the reasons declining Chinese dynasties had such fiscal problems, for instance, is that the tax surveys only got updated every two centuries or so, such that a major provincial lord was still only paying 20 silver pieces in taxes, when he should’ve been paying 20,000 (and his peasants were all paying 20 when all they could afford was 2).

In other words: unless the spreadsheet boys periodically go out and check that the numbers on their spreadsheets actually correspond in some systematic, more-or-less representative way to some underlying social reality, government policy is being set by make-believe.

Severian, “The Finger is Not the Moon”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-09-14.

November 27, 2024

Trump’s plan to dismiss transgender troops will apparently “gut” the US military

As if the US military services hadn’t suffered enough from their own government, it’s now being widely asserted in the media that Trump’s declared plan to get rid of all current transgender service members will be a desperately hard blow to an already over-stressed military structure:

The news media is calmly warning that Donald Trump is planning to ban transgender servicemembers from the American military, which will absolutely gut the armed forces.

Sample claim, from Newsweek, quoting the leader of an LGBT advocacy nonprofit:

Abruptly discharging 15,000-plus service members, especially given that the military’s recruiting targets fell short by 41,000 recruits last year, adds administrative burdens to war fighting units.

There would be a significant financial cost, as well as a loss of experience and leadership that will take possibly 20 years and billions of dollars to replace.

We’ll practically have no military left! It would be like a whole infantry division suddenly just vanishing: 15,000-plus transgendered service members.

You’re going to see this number a lot in the weeks ahead. The New Republic, today: “Donald Trump’s plan to ban transgender people from the military would have a devastating effect: At least 15,000 members would be forced to leave.”

That number comes from a 2018 report by the now-defunct Palm Center, a pro-LGBT independent research institute in California, which reached this conclusion: “Transgender troops make up 0.7% (seven-tenths of one percent) of the military (Active Component and Selected Reserve)”. Their best guess about a total number: 14,707. The media is just rounding that number up to the next thousand.

The Palm Center … extrapolated a lot, let’s say, in good part by multiplying their guess about a percentage, derived from a grossly inadequate survey of a select number of active duty troops, times the total number of servicemembers. Page 4:

Assuming that the distribution of transgender men and women is roughly equivalent in the Active and Selected Reserve Components, it is possible to derive an estimate of the number of transgender troops in the Selected Reserve as follows. The number of transgender women is .0066 x 652,623 = 4,307 and the number of transgender men is .0091 x 156,080 = 1,420. The total number of transgender members of the Selected Reserve is 4,307 + 1,420 = 5,727. And, the total number of transgender troops is 8,980 (active) + 5,727 (reserve) = 14,707.

Assuming the distribution, it is possible to derive an estimate. That’s the basis of the 15,000 number that you’ll see in news stories. Remember that language.

Similarly, a 2016 RAND study offered these findings (among others), and note the remarkable thing that happens between the first and second paragraph:

It is difficult to estimate the number of transgender personnel in the military due to current policies and a lack of empirical data. Applying a range of prevalence estimates, combining data from multiple surveys, and adjusting for the male/female distribution in the military provided a midrange estimate of around 2,450 transgender personnel in the active component (out of a total number of approximately 1.3 million active-component service members) and 1,510 in the Selected Reserve.

Only a subset will seek gender transition–related treatment. Estimates derived from survey data and private health insurance claims data indicate that, each year, between 29 and 129 service members in the active component will seek transition-related care that could disrupt their ability to deploy.

So studies indicate that there are 3,960 transgendered servicemembers, and also that there are 14,707 transgendered servicemembers, and “between 29 and 129 service members in the active component” who will actively seek gender transition services in a typical year.

So it’s definitely somewhere between 29 and 15,000.

November 10, 2024

WW2 in Numbers

World War Two

Published 9 Nov 2024World War II wasn’t just the deadliest conflict in history — it was a war of unprecedented scale. From staggering casualty numbers to military production and economic costs, this episode breaks down the biggest statistics that defined the global conflict.

(more…)

November 2, 2024

QotD: UBI discourages low-income workers

Not only does it have a high cost, UBI drains the labour force by discouraging work and boosting leisure time, says one big-picture study

Earlier this month, a cross-border team of North American economists published the results of a landmark study, probably the best and most careful yet done, of how low-income workers respond to an unconditional guaranteed income. Not so long ago this would have been a plus-sized news item in narcissistic Canada, for the lead author of the study is a rising economics star at the University of Toronto, Eva Vivalt. The economists, working through non-profit groups, recruited 3,000 people below a certain income cutoff in the suburbs of Dallas and Chicago. A thousand of these, chosen at random, were given a thousand dollars a month for three years. The rest were assigned to a control group that got just $50 a month, plus small extra amounts to encourage them to stay with the study and fill in questionnaires.

That randomization is an important source of credibility, and the study has several other impressive methodological bona fides. If you have an envelope to scribble on the back of, you can see that the payments alone were beyond the wildest dreams of most social science: most of the money was provided by the AI billionaire Sam Altman. But the study also had help from state governments, who agreed to forgo welfare clawbacks from the participants to make sure the observed effects weren’t obscured by local circumstances. Participant households were also screened carefully to make sure nobody in them was already receiving disability insurance. (Free money doesn’t discourage work among people who can’t work — or who absolutely won’t.) And the study combined questionnaire data with both smartphone tracking and state administrative records, yielding an unusually strong ability to answer difficult behavioural questions.

The big picture shows that the free cash — a “universal basic income” (UBI) for a small group of individuals — discouraged paying work, even though everybody in the study was starting out poor. Labour market participation among the recipients fell by two percentage points, even though the study period was limited to three years, and the earned incomes of those getting the cheques declined by $1,500 a year on average. There is no indication that the cash recipients used their augmented bargaining power to find better jobs, and no indication of “significant effects on investments in human capital”, i.e., training and education. The largest change in time use in the experiment group was — wait for it! — “time spent on leisure”.

Colby Cosh, “Universal basic income is a recipe for fiscal suicide (for so many reasons)”, National Post, 2024-07-30.

October 7, 2024

The demographic impact of modern cities

Lorenzo Warby touches on some of the social and demographic issues that David Friedman discussed the other day:

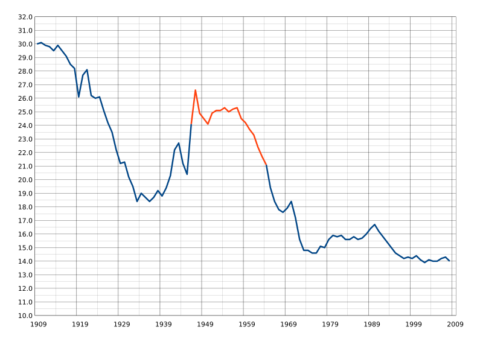

US Birth Rates from 1909-2008. The number of births per thousand people in the United States. The red segment is known as the Baby Boomer period. The drop in 1970 is due to excluding births to non-residents.

Graph by Saiarcot895 via Wikimedia Commons

Cities are demographic sinks. That is, cities have higher death rates than fertility rates.

For much of human history, cities have been unhealthy places to live. This is no longer true: cities have higher average life expectancies than rural areas. But they are still demographic sinks, for cities collapse fertility rates.

The problem is not that more women have no children, or only one child, making it to adulthood. Such women have always existed, though their share of the population has gone up across recent decades.

The key problem is the collapse in the demographic “tail” of large families. Cities are profoundly antipathetic to large families, and have always been so. This is particularly true of apartment cities — suburbs are somewhat more amenable to large families, though not enough to make up for the urbanisation effect.

While modern cities do not have slaves and household servants who were blocked from reproducing as ancient cities did, various aspects of modern technology have fertility-suppressing effects. Cars that presume a maximum of three children, for instance. An effect that is worsened by compulsory baby car-seats. Or ticketing and accommodation that presumes two children or less. There is also the deep problems of modern online dating. Plus the effects that endocrine disrupters and falling testosterone may be having.

These effects also extend to rural populations: falling fertility in rural populations is far more of a mystery than falling fertility in urban populations. How much declining metabolic health plays in all this is unclear. Indeed, futurist Samo Burja is correct, we do not really understand the “social technology” of human breeding.

Be that as it may, cities as demographic sinks is a continuation of patterns that go back to the first cities.

Matters at the margin

There are factors at the margin known to make a difference. Religious folk breed more than secular folk, though that is in part because rural people are more religious and city folk more secular.

Educating women reduces fertility. This is, in part, an urbanisation effect, as more education is available in cities. It is also an opportunity cost effect — there is more to do in cities, both paid and unpaid.

Education increases the general opportunity cost of motherhood, by expanding women’s opportunities. This also makes moving to cities more attractive. Women having more career opportunities reduces the relative attractiveness of men as marriage partners, reducing the marriage rate.

Strong cultural barriers against children outside marriage can reduce the fertility rate, by largely restricting motherhood to married women. This makes the fertility rate more dependant on the marriage rate.

Educating women makes children more expensive, as educated mothers have educated children. Part of the patterns that economist Gary Becker analysed.

September 21, 2024

Statistics Canada notes significant decline in life satisfaction and hope for the future

In one sense, we should be quite used to Statistics Canada giving us unwelcome economic news, given the state of the Canadian economy over the last decade. What seems less in character is that they’re connecting the dots between our obvious national financial decline and showing how directly it has impacted ordinary Canadians’ views about life in Canada and what they expect in the future:

Life satisfaction among Canadians is on the decline. Based on data from the Canadian Social Survey, levels of life satisfaction have been tracking downward since the summer of 2021, when quarterly monitoring of key Quality of Life indicators began. Less than half (48.6%) of Canadians aged 15 years and older were feeling highly satisfied with their lives in 2024, down from 54.0% three years earlier.

Not only is life satisfaction down, but so is hopefulness about the future, which dropped from 65.0% to 59.7% from 2021 to 2024. These results are based on a new study released today, “Charting change: How time-series data provides insights on Canadian well-being”, which sheds light on changes in overall life satisfaction, hopeful feelings about the future and financial well-being. It examines differences and trends across various dimensions, such as age, gender, racialized and non-racialized populations, and 2SLGBTQ+ populations.

Decline in life satisfaction more common among young adults and racialized Canadians

Life satisfaction can be considered a pulse check on Canadians’ overall well-being. While this indicator of subjective well-being has been declining for the past few years, there is nonetheless substantive variation in life satisfaction across different demographic groups. Younger adults (aged 25 to 34) had notable declines in their life satisfaction in 2024, with their proportions declining an average of 3.9 percentage points per year since 2021. By 2024, fewer than 4 in 10 (36.9%) of these adults were highly satisfied with their lives.

Meanwhile, seniors (aged 65 and older) maintained their high level of satisfaction, with 61.5% being happy with their lives in 2024. This measure of subjective well-being has remained relatively stable among senior Canadians since 2021.

In addition, racialized Canadians, who are younger on average than non-racialized Canadians, saw greater drops in life satisfaction than their non-racialized counterparts. The proportion of racialized Canadians reporting high levels of life satisfaction fell from 52.7% in 2021 to 40.6% in 2024. This decline was more than five times higher than the decrease observed for non-racialized Canadians, who experienced a decline in life satisfaction of 0.8 percentage points per year from 2021 to 2024. In 2024, over half (51.5%) of non-racialized Canadians were happy with their lives.

It really is a bad sign when the largest province in Confederation is also becoming the most disheartened by its economic prospects:

August 19, 2024

Bret Devereaux on Nathan Rosenstein’s Rome at War (2004)

Although Dr. Devereaux is taking a bit of time away from the more typical blogging topics he usually covers on A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, he still discusses books related to his area of specialty:

For this week’s book recommendation, I want to recommend N. Rosenstein, Rome at War: Farms, Families and Death in the Middle Republic (2004). This is something of a variation from my normal recommendations, so I want to lead with a necessary caveat: this book is not a light or easy read. It was written for specialists and expects the reader to do some work to fully understand its arguments. That said, it isn’t written in impenetrable “academese” – indeed, the ideas here are very concrete, dealing with food production, family formation, mortality and military service. But they’re also fairly technical and Rosenstein doesn’t always stop to recap what he has said and draw fully the conclusions he has reached and so a bit of that work is left to the reader.

That said, this is probably in the top ten or so books that have shaped me as a scholar and influenced my own thinking – as attentive readers can no doubt recall seeing this book show up a lot in my footnotes and citations. And much like another book I’ve recommended, Landers, The Field and the Forge: Population, Production and Power in the Pre-Industrial West (2003), this is the sort of book that moves you beyond the generalizations about ancient societies you might get in a more general treatment (“low productivity, high mortality, youth-shifted age profile, etc.”) down to the actual evidence and methods we have to estimate and understand that.

Fundamentally, Rome at War is an exercise in “modeling” – creating (fairly simple) statistical models to simulate things for which we do not have vast amounts of hard data, but for which we can more or less estimate. For instance, we do not have the complete financial records for a statistically significant sample of Roman small farmers; indeed, we do not have such for any Roman small farmers. So instead, Rosenstein begins with some evidence-informed estimates about typical family size and construction and combines them with some equally evidence-informed estimates about the productivity of ancient farms and their size and then “simulates” that household. That sort of approach informs the entire book.

Fundamentally, Rosenstein is seeking to examine the causes of a key Roman political event: the agrarian land-reform program of Tiberius Gracchus in 133, but the road he takes getting there is equally interesting. He begins by demonstrating that based on what we know the issue with the structure of agriculture in Roman Italy was not, strictly speaking “low productivity” so much as inefficient labor allocation (a note you will have seen me come back to a lot): farms too small for the families – as units of labor – which farmed them. That is a very interesting observation generally, but his point in reaching it is to show that this is why Roman can conscript these fellows so aggressively: this is mostly surplus labor so pulling it out of the countryside does not undermine these households (usually). But that pulls a major pillar – that heavy Roman conscription undermined small freeholders in Italy in the Second Century – out of the traditional reading of the land reforms.

Instead, Rosenstein then moves on to modeling Roman military mortality, arguing that, based on what we know, the real problem is that Rome spends the second century winning a lot. As a result, lots of young men who normally might have died in war – certainly in the massive wars of the third century (Pyrrhic and Punic) – survived their military service, but remained surplus to the labor needs of the countryside and thus a strain on their small households. These fellows then started to accumulate. Meanwhile, the nature of the Roman census (self-reported on the honor system) and late second century Roman military service (often unprofitable and dangerous in Spain, but not with the sort of massive armies of the previous centuries which might cause demographically significant losses) meant that more Romans might have been dodging the draft by under-reporting in the census. Which leads to his conclusion: when Tiberius Gracchus looks out, he sees both large numbers of landless Romans accumulating in Rome (and angry) and also falling census rolls for the Roman smallholder class and assumes that the Roman peasantry is being economically devastated by expanding slave estates and his solution is land reform. But what is actually happening is population growth combined with falling census registration, which in turn explains why the land reform program doesn’t produce nearly as much change as you’d expect, despite being more or less implemented.

Those conclusions remain both important and contested. What I think will be more valuable for most readers is instead the path Rosenstein takes to reach them, which walks through so much of the nuts-and-bolts of Roman life: marriage patterns, childbearing patterns, agricultural productivity, military service rates, mortality rates and so on. These are, invariably, estimates built on estimates of estimates and so exist with fairly large “error bars” and uncertainty, but they are, for the most part, the best the evidence will support and serve to put meat on the bones of those standard generalizing descriptions of ancient society.

August 14, 2024

Premier Doug Ford’s weird plan to hold the justice system to account

The problem with Premier Ford’s as-yet-unelaborated plan to collect formal statistics on the products of the criminal justice system is that it’s weird. And Canadians don’t like weird things because something something Donald Trump something something Hitler. Despite that, Colby Cosh thinks it’s a good idea:

Superior Court of Justice building on University Avenue in Toronto (formerly the York County Court House).

… the very idea of addressing a social problem by gathering quantitative information is so un-Canadian as to seem radical and startling. It certainly seemed that way to the lawyers and civil libertarians who freaked out at Ford’s mention of “accountability” for judges who fail to protect the public from criminal predators.

Judicial independence is an axiom of our constitution — but to the degree that judges become policymakers, which is perpetually increasing as they discover creative new applications of the Charter, their lack of oversight by elected legislators and by the voting public is also a serious and obvious problem, purely in principle. It is no wonder the legal guild takes fright at the notion of “accountability” if it is interpreted to mean that judges might be subject to enforceable performance measures or firing by a minister.

But, of course, the word “account” is visible in there, and measurement of a social crisis is necessary to establish that one exists, even if almost everybody believes it to exist. Our courts are the first to castigate a government that makes some legislative change affecting individual rights without an attempt at inquiry into its reasonability and urgency. Ford, in proposing to establish the dimensions of preventable re-offending, is doing exactly what a legislator hoping to reduce crime ought to do: gather numbers. Collect and publish information. And let us specify that we mean publish publish, in an open, dependable, accessible way, with maximum detail.

Frankly, Ford’s announcement seems as much as anything like a reaction to being backed into a corner by an unresponsive Liberal government, which controls bail policy and the content of the Criminal Code, and by judges, whose irrational bail and sentencing decisions flood what’s left of our news media. Provincial politicians are bound to be judged by voters on the perceived prevalence of crime, but about all they can actually do about it is to, well, buy more choppers for the coppers and start collecting local data about revolving-door justice.

Update: Fixed broken link.

July 20, 2024

QotD: Comparing gun crime in Canada and the United States

That may explain the extraordinary amount of sucking up to Canada in this movie [Bowling for Columbine], which, while gratifying to insecure Canucks and self-loathing Americans, may be of less interest to third parties. Moore’s thesis, such as it is, is that America’s murder rate is the consequence not just of the country’s love of guns but of deeper currents of paranoia and fear in the American psyche. To that end, he crosses the Michigan border into Ontario, where one Canadian after another tells him that they don’t lock their doors. The level of guns per capita in Canada is similar to America but the murder rate is much, much lower. Ergo, it must be because Americans are living in fear while Canadians are much more socially progressive.

Whatever, dude. Unlike Moore, I have homes on both sides of the border and it’s the Quebec one I keep locked. By the time you read this, I’ll be in New York, but my home in New Hampshire will be unlocked, and so will my car at the airport, the key in the ignition, so I’ll know where to find it. By contrast, in Quebec it’s illegal to leave your car unlocked, even if you stop for a pee on an ice floe up by Hudson’s Bay. Pace Moore, Canada has vastly lower rates of handgun ownership. Long-gun ownership is much closer, but, statistically, Canadians are slightly more murderous than Americans in this sphere: in the US, there are 1.7 homicides per 100,000 long guns; in Canada, it’s 1.9. So European visitors to North America should be aware they’re more likely to be killed by a homicidal Canadian rifleman than an American one.

On the overall murder rate, if Moore’s interested in “cultural differences”, it seems odd that he should avoid the most obvious one. Alberta Report‘s Colby Cosh, a braver man than I, points out that black Americans are 13 per cent of the US population but commit over half the murders. Once you factor those out, non-black Americans murder at about the same rate as Canadians.

Mark Steyn, “Bowling for Columbine”, Steyn Online, 2002-11-30.

July 4, 2024

Argentina’s inflation rate

As you may have noticed, my interest in Argentinian affairs increased a lot with the election of Javier Milei as President. His first six months in office, while turbulent, do seem to have the economic indicators moving in the right direction for ordinary Argentines:

Argentina’s inflation rate has recently dropped to its lowest point since January 2022, registering a monthly increase of 4.2 percent in May according to the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INDEC). Although annual inflation has slowed for the first time since mid-2023, it still stands at 276.4 percent, one of the highest rates globally.

When Javier Milei assumed the presidency in December 2023, monthly inflation had skyrocketed to an unprecedented 25.5 percent. Within five months, Milei’s administration managed to reduce this figure by more than 20 percentage points. Despite the persistently high annual inflation rate, the trend indicates potential stabilization of the Argentine economy.

Javier Milei’s reforms have been described as aggressive. In his inaugural speech, he emphasized the need to clean up the economy before implementing his promises to dollarize and close the central bank.

To achieve a zero deficit, Milei enacted a 35 percent reduction in public spending. He achieved this by closing half of the ministries and secretariats, suspending public works for a year, reducing subsidies for energy and transportation, canceling government advertising, and maintaining the 2023 budget for 2024 despite an inflation rate of 300 percent. Essentially, the government drastically cut its expenditures.

These measures, although unpopular, yielded results. Milei’s government not only avoided a deficit, but achieved a surplus, and most importantly, inflation began to decline.

Following the inflation story in Argentina recently brought to mind Henry Hazlitt’s famous 1978 article “Inflation in One Page“. As the title suggests, Hazlitt summarizes the causes and remedies of inflation in a brief and simple explanation. He argued that inflation is a consequence of government monetary policies, specifically excessive money printing due to unbalanced budgets caused by extravagant government spending.