Every single ministry or government department has been writing police-power regulation into their revised policy statements for the last 20 years. It is incremental and surreptitious. I mean come on, if you were going to abrogate democracy, cheat in every election, remove property rights from every citizen, bank that property in multinational/UN hands, you would need a police state, amIright?

That said, the province where I live, which is so crazy, it’s where California gets most of its bonkers ideas, has turned, locally-speaking. The socialists and greens were so confident of sweeping their elections that they didn’t bother to cheat, and as a result most every town and city was taken back by people saying, nope, you’re done. We are going back to basics. Like no more outdoor drug bazaars, silly wasteful green projects, and here’s an idea: let’s respond to our voters and not try to steal everything they have.

This would happen in every single state and county if we managed to stop them cheating. Because trust me, in every election in every jurisdiction, they are cheating.

The catastrophe even reached Davos. When one of their extra-special places is under threat time to roll out the big guns.

Hence 15-minute cities. Get this damn thing done before the slow learners, i.e. city people, wake up.

Therefore Oxford City Council this past week instituted their trial of 15 Minute Cities. This is a UN/WEF project meant to continue the lockdowns by scaring us to death using the nonexistent climate crisis. And if you think this is local to the UK, it’s not. This is being trialed in Brisbane, Portland, Barcelona, Paris and Buenos Aires.

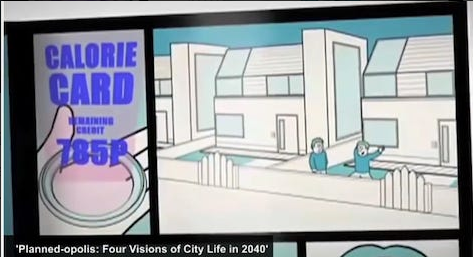

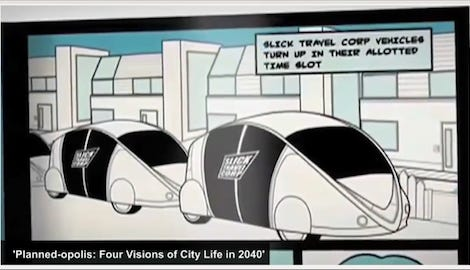

Here are the basic rules. You are allowed out of your neighborhood for fifteen minutes a day and out of your region, 100 days a year. Fifteen minutes is enough to shop, take your kids to school and pick them up. Trespass that and you’re fined. Oxford has approved the installation of electronic traffic filters, placed strategically, which will be able to track your car, wherever it goes. That will cost citizens around $15,000,000. We get to build our own prisons!

The trial lockdown goes into effect January 1, 2024

People voted for this. Or rather they didn’t, but did.

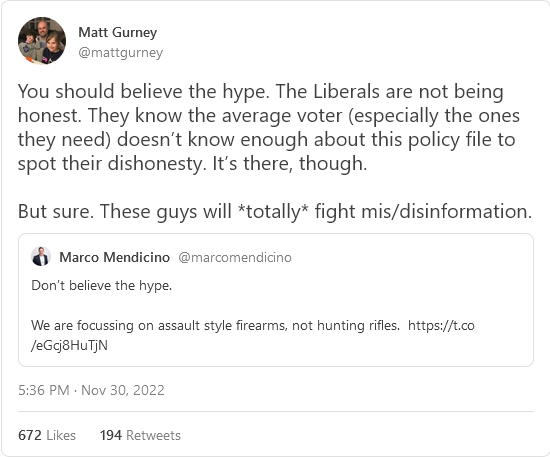

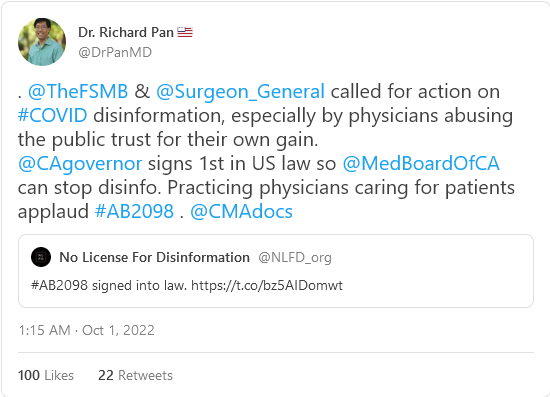

Seems preposterous doesn’t it? Yet those who still read and watch legacy media know about it. They have been selling it hard. When I mean “they”, I mean the massive PR firms paid by WEF and the UN, strategized no doubt by McKinsey.

To refresh, this is what they want: drive people out of rural areas, and place them in 15 minute cities. Take all the resources, and divide them up among multi-nationals who will then tax our use of water, air, minerals, etc. Creating a world of renters, of serfs. You will have a lovely category: Amazon serf, Tesla serf. Bill Gates’ serf.

Pretty much every city council in every city in the world has had 15 Minute Cities pitched to them. Without doubt, every single city council in the world, has some committee and elected officer assigned to the 15 Minute city project. They are “researching” it with your money, which means they are trying to find a way to convince people to sign onto it.

They only got here because we stopped paying attention. No one went to meetings, no one followed what they were doing in committee. We trusted them. As someone pointed out, WEF and the UN during COP26 hold meetings and lectures that show precisely what they are planning to do, that are videotaped and available to anyone who wants to know what they are planning. Views of each? 26 people. 50 tops.

I’d like to advise you to get involved with your local government, because they have undoubtedly gone rogue and are amassing power and attaching funding requirements to each project. Many of them, if green-based, and locally everything is green-based, will be ill-founded, the science can be exploded. At our last virtual meeting here, a man from the real world, with real skills made a presentation showing that our local government was selling a fraudulent idea, and had put itself at risk legally. They had used a flawed study checked by no adult, sloppily researched and written by a university student to create the climate policy. Instead of being an ideal carbon sink, as was claimed, it turned out the islands were much less effective in that regard than other parts of the province.

Our local government had used this study for the past year, to harangue citizens and senior governments to push for more restrictive regulation on islanders.

The New World Order is built on sand, it is feather-weight, it can be blown over by a single honest consultant who can read legislation and do math. Become one. It is super satisfying. And the friends you will make will last beyond the grave.