Melanie in Saskatchewan explains why the constant Liberal talking point that refusing to get a particular security clearance “proved” that Pierre Poilievre was next-door to a traitor will probably not be raised any more:

Open Letter to Canada’s Security Clearance Scolds: Carney Just Proved Pierre Right!

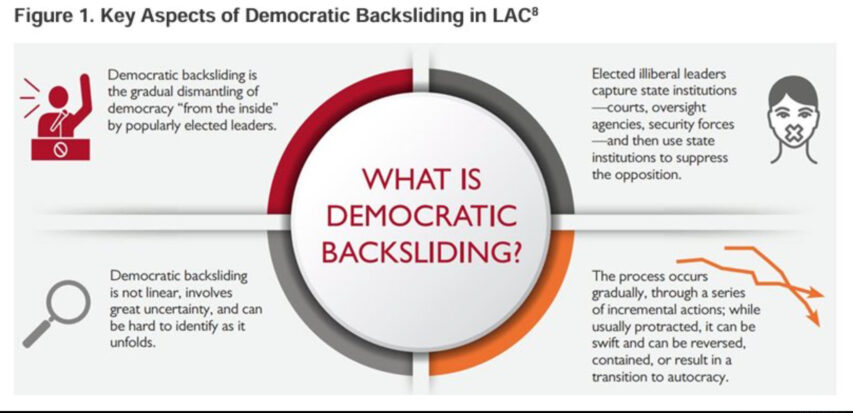

To every Liberal and NDP partisan who has spent the last year yelling “security clearance” like it is a magic spell that turns criticism into treason, congratulations. Mark Carney just demonstrated Pierre Poilievre’s point for him, on camera, in real time.

The moment came on March 3, 2026, during Prime Minister Mark Carney’s Indo-Pacific trip. After meetings in India with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Carney held a press availability with Canadian media while travelling through the region. The topic journalists wanted clarified was not subtle. They asked about foreign interference linked to India and the 2023 assassination of Sikh activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar in Surrey, British Columbia, the allegation that detonated Canada’s diplomatic crisis with India.

The question came from Dylan Robertson of The Canadian Press during the media scrum. He asked directly whether Carney believed India continued to engage in foreign interference or transnational repression targeting Canadians.

Carney swerved. He was asked again. And again.

Eventually, after the careful circling that seasoned politicians deploy when a straight answer would be inconvenient, he landed on the tell. Not the kind you need a polygraph for. The kind you publish in a civics textbook.

Here is what he said, exactly:

There will not be consequences for those officials … There are aspects of those briefings that I can’t share in public, and I’m not going to betray them. I will tell you that there is progress on these issues.

Read that again, slowly, with a spoon handy in case you choke on the irony. Because this is the whole debate in one neat little ribbon.

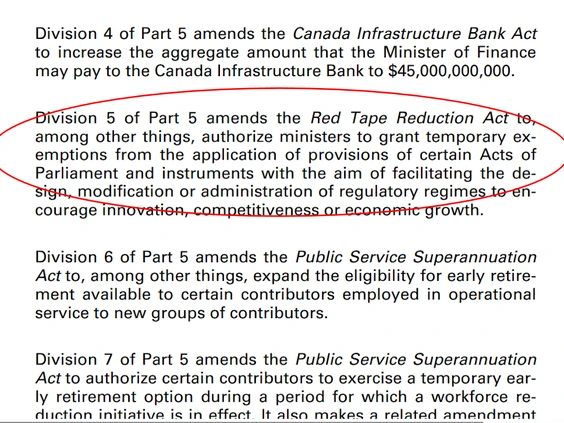

Pierre Poilievre’s argument, from the start, has been that the particular classified briefings being pushed would place him inside a legal box. Once inside it, the rules governing those briefings restrict what he can say publicly and how he can use the information while doing his job as Leader of the Opposition. Global News reported Poilievre’s office saying officials told them the briefing structure could leave him legally prevented from speaking publicly about certain information except in narrow ways, which they argued would “render him unable to effectively use any relevant information he received”.

Now watch what just happened.

Carney, the man with the clearance and the briefings, is asked direct questions about one of the most explosive foreign-interference files in modern Canadian politics.

And his answer, translated into plain English, is simple: I cannot share what I know.