In The Critic, John Sturgis reviews a new book by Luke Turner titled Men at War: Loving, Lusting, Fighting, Remembering 1939-1945, which considers the myths and reality of wartime relationships during the Second World War:

Spitfire pilot Ian Gleed shot down five enemy aircraft in just a week in May 1940 — the fastest time in which this had ever been done, making him an official “ace” who would be quickly promoted to Wing Commander.

Gleed had become a poster boy for “the few”, the hero pilots of the Battle of Britain to whom so many would owe so much. He lived up to the popular image with his talk of “a bloody good show” and shooting down “damned Huns”, after which he’d sink a few warm beers and spend some “wizard” free time recuperating with his girlfriend Pam, whom he “loved now more than ever”.

Gleed’s luck finally ran out over Tunisia in April 1943 when his plane was hit by a German fighter and crashed into dunes. Gleed was killed. He was just 26.

It would only emerge decades later that much of the popular image he had cultivated simply wasn’t true. Gleed was gay. Pam was an imaginary character he had invented as a cover to keep his double life as a sexually active homosexual firmly secret.

Gleed’s story is one of many similar vignettes in this alternative history of the Second World War. Its author Luke Turner’s previous book was a memoir about his own grappling with issues around his identity as a bisexual. Here he takes up the question of how this would have played out for him and other sexual non-conformists in 1939–45.

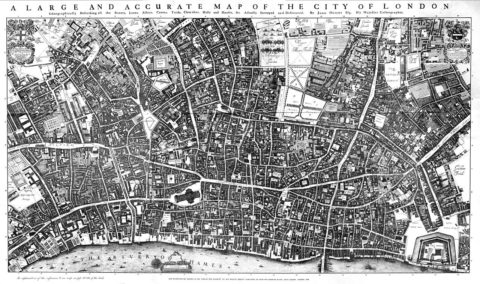

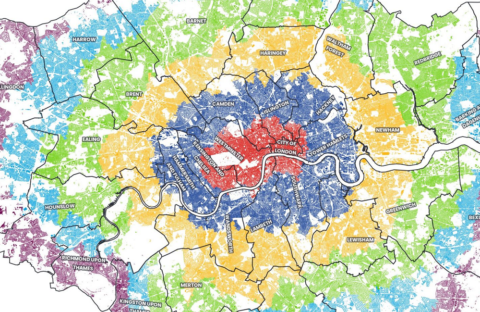

Turner grew up obsessed with the war — everything from Airfix kits and Dad’s Army to Stalingrad and the Berlin bunker — and here he examines what it was to live through that period as a sexually active person of whatever hue. It proves a particularly rich subject matter as sex seems to have been everywhere in war time: everyone was sleeping with everyone else, apparently. It’s a perennial truth that you or I might be hit by a bus tomorrow — but make that bus a bomb, and suddenly this seems to create a sense of urgency which frequently manifests itself sexually, lending daily life what Turner calls “an aphrodisiac quality”. As Quentin Crisp put it when describing the shenanigans in blacked-out, Blitz London: “As soon as the bombs started to fall, the city became like a paved double bed.”

Whilst war may see an explosion of sex of all kinds, the establishment was not always comfortable with this. A Home Office report on public behaviour in London during the Blitz noted, “In several districts cases of blatant immorality in shelters are reported; this upsets other occupants of the shelters.”

One contemporary account suggests, “In wartime a uniform, whether of the Army, Navy or Air Force, to the average girl ranks as a fetish.” This had consequences in the field: Dear John letters from home could be a real problem in this regard. As an Army report in 1942 put it, morale is often damaged by “the suspicion, very frequently justified, of fickleness on behalf of wives and girls”.

Amongst all this sex was, of course, sex with Americans. Turner cites George Formby who captured this mood in the song “Our Fanny’s Gone All Yankee”: “She don’t wait for the dark when she wants to have a lark/In a bus or train she does her hanky panky.”

Then in a dark reversal of this two-nations-colliding-sexually motif, we get the horror of the Red Army’s organised rape of as many as 1.4 milllion German women during the Russian advance on Berlin, whose residents would later refer to the city’s grandiose monument to Soviet war dead as “the tomb of the unknown rapist”.