Joolz Guides – London History Walks – Travel Films

Published 7 Jan 2018Funny English Idioms – and why we say them!

English people use some funny idioms and expressions. We love them, especially if they are about going to the toilet!

Subscribe on Youtube ➜ https://www.youtube.com/joolzguides

Joolz Guides website to book a private tour ➜ http://joolzguides.com/

Julian McDonnell, that’s me, runs a London vlog and youtube channel where he talks about all things to do with London which you may not have known. This includes language and the way English people speak. Amongst many other funny idioms for going to the toilet one of the oldest ones is “To Spend a Penny”. This came about because it used to cost one penny to go to the public lavatories when they first appeared on the streets in 1851!

Hopefully this video will help you to understand the origins of these funny English idioms and expressions and help you to learn English or they may even be helpful if you are an ESL teacher or TEFL.

Another funny English idiom is when we say “He was sent to Coventry”. This indicates somebody who has been ostrasized and no one wants to talk to. Watch the video to find out how this came about.

Did you ever hear someone use the idiom “To hear a pin drop”? This actually originates from the tea auctions where you were only allowed to bid for a certain amount of time. They put a pin into a candle and let it burn down. When the pin fell out if there were no more bids you could hear a pin drop!

Our fourth funny idiom is a baker’s dozen. Anyone will tell you that a dozen is 12 but a baker’s dozen is 13! This is because in 1266 there was a law that would penalise bakers if they sold less than they said they were selling! So to make sure they weren’t short of their weight they would add a thirteenth loaf just to make sure.

Then comes our final idiom – To be on the wagon.

This means that someone is not drinking alcohol and it originates from the days when criminals would be hanged. They would stop at the Resurrection Gate pub and be bought one last drink but after that drink they had to get back onto the wagon and couldn’t drink any more. Then the wagon would take them to the gallows.

To make it more fun I have tried to show some of the locations which would have been affected by these expressions as well as point out some interesting historical facts which are related to them.

I go to Twinings in The Strand, The Royal Exchange, Pudding Lane and St Giles in the Fields

SUPPORT MY CHANNEL ON PATREON ➜ https://www.patreon.com/joolzguides

DONATE TO MY CHANNEL WITH PAYPAL ➜ https://www.paypal.me/julianmcdonnell

November 16, 2019

Funny English Idioms – and why we say them!

November 8, 2019

Don’t hold your breath waiting for the Feds to tackle Quebec’s ongoing repression against minorities

Chris Selley on the situation in Quebec, where first-class citizenship is only available to those who speak French and don’t expect their religious beliefs to be respected:

One of the fascinating things about Quebec politics is that it’s often impossible to predict which absurdities will become controversial and which will be accepted as reasonable. The province’s linguistic and more recently cultural debates operate in an atmosphere so divorced from normal reality that it’s impossible to know how any new idea or event might react to its unique and volatile mixture of gases.

The classic example is Pastagate: An inspector from the Office québécois de la langue française found an Italian restaurant’s menu was riddled with Italian — calamari, antipasti — and issued the appropriate cease-and-desist notice. At no point did anyone suggest he had misinterpreted the law. Despite universal scorn and worldwide mockery, at no point did anyone successfully explain why this inspector’s actions were obviously ultra vires, while the OQLF’s other insane diktats — say, forcing a bilingual community newspaper to segregate English-language and French-language content such that English-only advertising will never appear on the same page as a French-language article — were reasonable.

As a result, Quebec politics is like a festival of trial balloons. Most recently we saw languages minister Simon Jolin-Barrette float the idea of banning merchants from greeting customers with “bonjour-hi” — a Downtown Montreal-ism that turns language hawks crimson with rage — only to have Premier François Legault shoot it down a couple of days later amidst widespread ridicule.

By contrast, we’re supposed to think it’s totally reasonable that the National Assembly voted merely to request that merchants use state-sanctioned greetings. Unanimously. Twice.

Ban religious symbols for all civil servants, or only those “in a position of authority”? Which civil servants are “in a position of authority”? Should currently employed civil servants affected by Bill 21 be grandfathered in or not? You can poll all you like, but until any given idea goes through Quebec’s intense media ringer, no one knows how it’ll shake out. With fundamental rights at stake, the majoritarian randomness of it all is truly alarming.

November 6, 2019

QotD: “Fake news” is nothing new

… the basic ideas of “alternative facts” and “fake news” — our updated, revved-up forms of disinformation — were not foreign to Orwell. Working at the BBC as a news producer — a fancy term for war propagandist — he heard some of the Axis powers’ propaganda as well as that of his own side (even if he kept his own hands fairly clean). He justifiably feared that the very concept of objective truth was fading from the modern world. Winston Smith’s job at the Ministry of Truth is to rewrite or “rectify” history, so that it follows the current party line, whatever it may be at that moment.

Orwell himself saw all this happen when he read Catalan newspapers as well as British ones during the Spanish Civil War, several years before joining the BBC. Condemning press distortions, above all how several English newspapers reported the war, he wrote: “I saw great battles where there had been no fighting and complete silence where hundreds of men had been killed … I saw, in fact, history being written not in terms of what happened but what ought to have happened according to various ‘party lines.'” Given the gridlock in American politics, and the never-ending verbal warfare between news outlets on the Right such as Fox News and on the Left such as MSNBC, Orwell appears all too accurate in his “predictions.”

One of the features of the world of Oceania reflecting Orwell’s prescience is its official language, Newspeak, an argot resembling a kind of Morse code that satirizes advertising norms, political jargon, and government bureaucratese. The purpose of Newspeak is to limit thought, on the view that “you can’t think what you lack the words for.” Ultimately, this impoverished language seeks to narrow and control human thought. (Does Twitter represent a step in that direction?) Purged of all nuance and subtlety, denuded of variety, and reduced to a few hundred simple words, Newspeak ultimately promises to render all independent thought (or “thoughtcrime”) impossible. If it cannot be expressed in language, it cannot be thought. And anything can fill the vacuum, such as 2 + 2 = 5. That is the equation — a perfect example of “doublethink” — which O’Brien indoctrinates Winston to accept in Room 101 and which marks the final step of the latter’s brainwashing. As the Party defines it, “doublethink” consists in holding “two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them.” In 2018, Trump’s lead lawyer, former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani, declared in a TV interview: “Truth isn’t truth.” A few months later, a talking head defended a critical news report on the grounds that, just because it is “not accurate doesn’t mean it’s not true.”

It testifies both to the brilliance of Orwell’s vision and to the bane of our times that Nineteen Eighty-Four retains so much relevance.

John Rodden and John Rossi, “George Orwell Warned Us, But Was Anyone Listening?”, The American Conservative, 2019-10-02.

October 28, 2019

QotD: Latin versus English

In a sensible language like English important words are connected and related to one another by other little words. The Romans in that stern antiquity considered such a method weak and unworthy. Nothing would satisfy them but that the structure of every word should be reacted on by its neighbours in accordance with elaborate rules to meet the different conditions in which it might be used. There is no doubt that this method both sounds and looks more impressive than our own. The sentence fits together like a piece of polished machinery. Every phrase can be tensely charged with meaning. It must have been very laborious, even if you were brought up to it; but no doubt it gave the Romans, and the Greeks too, a fine and easy way of establishing their posthumous fame. They were the first comers in the fields of thought and literature. When they arrived at fairly obvious reflections upon life and love, upon war, fate or manners, they coined them into the slogans or epigrams for which their language was so well adapted, and thus preserved the patent rights for all time. Hence their reputation.

Winston Churchill, My Early Life, 1930.

October 6, 2019

The cultural influence of George Orwell

George Orwell, the chosen pen name of Eric Blair, is one of the best known writers of the 20th century and even people who have never read any of his writings are aware of his influence. John Rodden and John Rossi outline the immediate post-war period that saw Orwell publish his final and best-known work:

Seven decades ago on June 8, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four exploded on the cultural front—fittingly enough, just two months before the Soviet Union’s first successful atomic test that August, which broke America’s nuclear monopoly. Orwell’s warning was urgent — and timely. Almost overnight, in the wake of the surrender of Germany and Japan that ended World War II in 1945, a new war—the so-called Cold War — had emerged. (Orwell is often credited with coining the term.)

The Cold War pitted the capitalist West against the communist East, above all the United States against the USSR (and soon China). Just three weeks before the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Soviet Union lifted the Berlin Blockade, thereby avoiding a potentially deadly showdown with the West that might have triggered World War III. Two weeks later, on May 23, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) was officially established, effectively ending prospects in the near future of German reunification. On the very day of Nineteen Eighty-Four‘s publication, June 8, fears swept through liberal America of a growing Red Scare when a leaked document named numerous celebrities as Communist Party members (e.g., Helen Keller, Dorothy Parker, Fredric March, Danny Kaye, Edward G. Robinson). That same month, the communist armies of Mao Zedong captured Shanghai, and less than six months later on October 1, declared victory in the civil war against the American-backed Nationalists and the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

What educated person is not at least vaguely familiar with the language and vision of Orwell’s novel — even if he or she does not recognize the source? Indeed the very ignorance of the source represents an inadvertent tribute to the power of Orwell’s language and vision. Like Shakespeare’s poetry (“All the world’s a stage,” “To be or not to be,” “This above all: to thine own self be true”), so deeply have some of Orwell’s locutions become lodged in the cultural lexicon and political imagination that most people no longer recognize their author, let alone the source.

Today, as in the case of Shakespeare, hundreds of millions of people mouth Orwell’s coinages and catchphrases, such as “Big Brother” and “doublethink” — including his name as proper adjective, “Orwellian” (i.e., nightmarish, oppressive). And that’s just in English. Tens of millions more recognize and repeat them in foreign translations, as I [Rodden] discovered in our travels and teaching in the communist East Germany as well as in Asia. Rudimentary acquaintance with such locutions is regarded as a sine qua non of cultural literacy in English — even today, when prolefeed (mindless chatter) floods the print columns and dominates the airwaves.

Nineteen Eighty-Four represents Orwell’s Orwellian vision — in the form of a fictional anti-utopia (or “dystopia”) — of what a nightmarish, oppressive future might hold. It projects a world 35 years away — half the biblical lifespan of three score and ten. Having completed his novel by the end of 1948, Orwell flipped the last two digits to underscore his anti-utopian theme of a world turned upside down and inside out. Or so many scholars have reasonably claimed. The date resultant from the flipped digits also gave the novel its immediacy. Previous anti-utopias, such as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), had cast their ominous scenarios far into the future, which lessened their dramatic impact and tended to render them entertaining thought experiments. (Huxley’s action is set in the 26th century.) By contrast, Orwell’s dire future is too close for comfort — and depicts the planet in the immediate aftermath of a global nuclear war that has nearly annihilated the human species. His vision thus projects a world in which middle-aged readers in 1949 might find themselves in old age — and certainly their children and grandchildren were likely to witness it. (If he had lived, Orwell himself would have still been just 80 years old on April 4, 1984, when the story opens.)

September 29, 2019

QotD: Crony capitalists and corrupt politicians love tariffs

Any survey – and certainly any careful study – of the history and reality of tariff policy confirms that tariffs (and other trade restrictions) are almost always dispensed, not for any plausible public-interest reasons, but to satisfy the private interests of rent-seekers. Even if, contrary to fact, economic journals and textbooks were filled with several plausible scenarios under which trade restrictions can improve the economic well-being of home-country residents, the actual history of trade policy is that this policy is one in service to domestic plunderers.

Many who agree with me here will nevertheless scold me for using, à la Bastiat, the provocative word “plunderers.” But I stick to my choice of words.

“Plunderers” is descriptive, for plunder is in fact what trade restrictions are all about. For two and a half centuries now we proponents of free trade have played mostly on the rhetorical turf of protectionists. On this turf there are language biases galore, such as “trade deficit,” a lowering of home-country tariffs described as “concessions” to foreign countries, the arrival in the home country of especially low-priced imports condemned as “dumping,” and, indeed, the word “protection” itself. Also, don’t forget the constant, clanking parade of inapposite military and sports metaphors.

For two and a half centuries now we proponents of free trade have typically treated the efforts of rent-seekers and rent-dispensers to portray their use of the state to enrich themselves at the expense of others with intellectual and moral respect. Why?

No one attempts to intellectually rationalize the theft and violence committed by street gangs. No one attempts to rationalize shoplifting, vandalism, armed robbery, arson, or rape. (It would, do note, be child’s play for a competent economics graduate student to develop a coherent theory of “optimal gang violence” that shows that, under just the right set of circumstances, there is an “optimal” amount of gang violence that improves the national welfare.) We call these destructive exercises of theft, coercion, and violence “theft,” “coercion,” and “violence.” We call these predatory activities what they really are.

By calling protectionism what it really is – the plunder of the many by the politically powerful few – we more vividly and widely expose protectionism’s ugly and cruel reality.

Don Boudreaux, “Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2019-08-04.

September 13, 2019

QotD: Orwell’s campaign against the jackboot

In spite of my campaign against the jackboot — in which I am not operating single-handed — I notice that jackboots are as common as ever in the columns of the newspapers. Even in the leading articles in the Evening Standard, I have come upon several of them lately. But I am still without any clear information as to what a jackboot is. It is a kind of boot that you put on when you want to behave tyrannically: that is as much as anyone seems to know.

Others besides myself have noted that war, when it gets into the leading articles, is apt to be waged with remarkably old-fashioned weapons. Planes and tanks do make occasional appearances, but as soon as an heroic attitude has to be struck, the only armaments mentioned are the sword (“We shall not sheathe the sword until”, etc., etc.), the spear, the shield, the buckler, the trident, the chariot and the clarion. All of these are hopelessly out of date (the chariot, for instance, has not been in effective use since about A.D. 50), and even the purpose of some of them has been forgotten. What is a buckler, for instance? One school of thought holds that it is a small round shield, but another school believes it to be a kind of belt. A clarion, I believe, is a trumpet, but most people imagine that a “clarion call” merely means a loud noise. One of the early Mass Observation reports, dealing with the coronation of George VI, pointed out that what are called “national occasions” always seem to cause a lapse into archaic language. The “ship of state”, for instance, when it makes one of its official appearances, has a prow and a helm instead of having a bow and a wheel, like modern ships. So far as it is applied to war, the motive for using this kind of language is probably a desire for euphemism. “We will not sheathe the sword” sounds a lot more gentlemanly than “We will keep on dropping block-busters”, though in effect it means the same.

One argument for Basic English is that by existing side by side with Standard English it can act as a sort of corrective to the oratory of statesmen and publicists. High-sounding phrases, when translated into Basic, are often deflated in a surprising way. For example, I presented to a Basic expert the sentence, “He little knew the fate that lay in store for him” — to be told that in Basic this would become “He was far from certain what was going to happen”. It sounds decidedly less impressive, but it means the same. In Basic, I am told, you cannot make a meaningless statement without its being apparent that it is meaningless — which is quite enough to explain why so many schoolmasters, editors, politicians and literary critics object to it.

George Orwell, “As I Please” Tribune, 1944-08-04.

September 4, 2019

English spelling – a bit mad, but perhaps the best system around

Lindybeige

Published on 12 Nov 2015Support me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/Lindybeige

Many people think that the English system of spelling is just mad. The random quirks of history have certainly played their part, and today we have spellings that follow so many different rules that at times it can seem just random. However, here I argue that actually the fact that our spelling does not match our pronunciation is a strength, not just a weakness.

I see from the comments that several viewers have misunderstood me, and have thought that I am saying that only when people are reading English do they recognise words in the same way as we recognise faces. No, this is how people read in all languages. This being the case, phonetic spelling is not such a great advantage, since people are not decoding the words using sound, and spelling based on derivation has advantages.

Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

August 17, 2019

History Summarized: Malta

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published on 16 Aug 2019Go to https://NordVPN.com/overlysarcastic and and use code

OVERLYSARCASTICto get 75% off a 3 year plan and an extra month for free. Protect yourself online today!Malta, the Island of A Dozen Empires, chilling in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, is one of the most social butterflies in History. Having played host to or fought against every major power in the Mediterranean, this island bears a gorgeous architectural and linguistic record of its past, and is still a treasure to behold in the modern day. I’ve covered a lot of nations and empires in my time here, but between the rich cultural blends, the overflowing artistic treasures, and the Still-In-One-Piece-ness of it all, Malta may have one of the strongest claims to being the Winner of History in my book. What’s so special about Malta? Watch and find out!

NOTE on 7:00 – 7:08 — I’m cheating the time-scales a little here. This church, the Rotunda of Mosta, was actually built mid 1800s. Malta’s lavish church construction continued nearly unabated from C. 1565 to the modern day, so I use this example here — but St Paul’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta, shown from 6:27-6:33 is a better example of pure original Baroque construction. Honestly, all of the churches in Malta deserve a look if you’re curious.

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/sS5K4R3

August 6, 2019

English has become what Esperanto was designed to be

As a teen, I was quite curious about Esperanto … enough that I ended up buying several books in the language and making a few semi-serious attempts to develop fluency. I still have those books in my library, but I never actually achieved any firm grasp of Esperanto. It was the most successful of a number of attempts to create a universal second language, intended to allow people to communicate with others who did not speak their primary tongue. When I was young, I also believed that this was a way to reduce inter-cultural frictions and in at least a small way to lower the risks of war between nations. As I got older and more cynical, I realized that Douglas Adams probably had the truth of it in describing the Babel Fish from his novels:

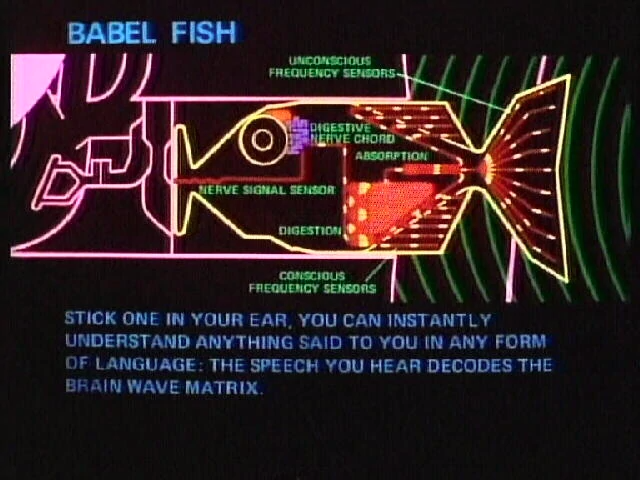

The Babel fish is small, yellow, leech-like, and probably the oddest thing in the Universe. It feeds on brainwave energy received not from its own carrier, but from those around it. It absorbs all unconscious mental frequencies from this brainwave energy to nourish itself with. It then excretes into the mind of its carrier a telepathic matrix formed by combining the conscious thought frequencies with nerve signals picked up from the speech centres of the brain which has supplied them. The practical upshot of all this is that if you stick a Babel fish in your ear you can instantly understand anything said to you in any form of language. The speech patterns you actually hear decode the brainwave matrix which has been fed into your mind by your Babel fish.

[…]

Meanwhile, the poor Babel fish, by effectively removing all barriers to communication between different races and cultures, has caused more and bloodier wars than anything else in the history of creation.

All that aside, Douglas Todd points out that despite all of its manifold complexities, the English language is actually taking on the role that Esperanto and other artificial languages were intended to do:

I recently travelled to the home of Ludwik Zamenhof, the Russian-Polish Jew who in 1873 invented Esperanto. It was intended to become the world’s first universal language.

Hoping it would end wars, Warsaw-based Zamenhof dreamed Esperanto would encourage people to come together under a common language. He thought that kind of connection would help overcome the distrust that can be exacerbated by the globe’s multi-language Tower of Babel.

Zamenhof’s vision of a common language caught on for hundreds of thousands. I have met people in Poland, South America and elsewhere who learned Esperanto as children. But, needless to say, the cause of Esperanto is now virtually lost.

Whether we like it or not, English is on the road to become the world’s lingua franca.

It is not the world’s most spoken language — that’s Mandarin. But English is arguably the language most commonly adopted as the medium of communication between speakers whose native languages are different.

I know I’m not the only Canadian who has travelled — in my case to Indonesia, Argentina, Denmark, Spain, Poland, Brazil, Turkey, Germany and elsewhere — and witnessed a collection of multilingual speakers suddenly revert to English, even if awkwardly, as they seek a shared way to talk.

It is a thing to behold. It is humbling.

As a native English speaker, I am not proud to say I only know about 1,500 words of French that I have trouble putting together in a meaningful way. I’m intimidated by new languages, whereas many friends and family are polyglots. So, for that matter, are most Europeans, where 97 per cent of 13-year-olds now study English.

It rarely ceases to amaze me when disparate multilingual people around the world show me and others their respect (and perhaps their pity) by speaking in English. Of course, most of them also like the chance to practise the language, since they know it is a key to new vistas.

July 29, 2019

QotD: Put up your dukes!

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1769–1852) by Thomas Lawrence, circa 1815-1816.

Wikimedia Commons.The phrase “duke it out”, meaning “fight”, appears to derive ultimately from a nickname of one of the Great Captains, the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852).

It seems that the Duke had a rather prominent nose, so distinctive, in fact, that his troops often referred to him as “Old Nosey”. So the word “duke” soon became a synonym for “nose” in working class English slang, attested during Wellington’s own lifetime. That, in turn, led to the rise of the threat “bust your duke”, meaning “punch your nose”, and thus to “duke buster” as slang for “fist”, which was soon shortened to “duke”.

By further evolution, the phrase “put up your dukes” developed as an invitation to fight and “duke it out” became slang for “fight”.

While some etymologists apparently do not agree with this derivation, it’s worth noting that there is in London a mini-monument to the ducal proboscis, suggesting how notable it was.

Al Nofi, “Al Nofi’s CIC, Issue 472”, Strategy Page, 2019-06-01.

July 18, 2019

QotD: “They might speak English, but they don’t speak Western”

[Responding to a photo of a protest sign labelled “Dumbledore wouldn’t let this happen“] I swear, it’s all you ever see from them.

But something happened to me last night, I had a kind of realization. It suddenly hit me WHY that is.

It’s because Harry Potter is literally all they collectively know.

Schools don’t teach history anymore.

They no longer teach the canon of Western literature.

They certainly don’t teach the Bible.So Millennials literally have no points of common reference. It’s not that they all just want to look like complete morons by infantilizing their political metaphor to the level of a children’s book, it’s that they have no other choice.

They’re literally bereft of the allegorical language of the West. I’m sure there’s some Harry Potter monster analogy I could use to explain it to them, how it’s like monsters have come along and literally stolen their ability to speak, their common language, and their birthright.

They can no longer express or understand the set of references we have from our past, our most prized stories, and our culture’s religious quotations. They can’t do Shakespeare, Milton, or even Mark Twain because they’ve never learned any of these while they were being taught Indonesian multicultural dancing and given participation awards. They don’t know what happened at Hastings in 1066, at Runnymede in 1215, or even at Sarajevo in 28th June 1914, because they were being given feminist diversity training instead of learning the history of their civilization. They certainly don’t know what “the least of these” refers to or where it comes from, as a recent event with a White House staffer proved.

They’ve lost the entire allegorical language of the West. They might speak English, but they don’t speak Western. To them, it’s like a foreign, dead, alien language. A set of stories they do not know.

RPGPundit, “Harry Potter and the way Millennial Leftists Don’t Even Speak Western Anymore”, The RPGPundit, 2017-02-02.

July 14, 2019

The Epstein scandal is another example of the importance of accurate names

ESR has some concerns about the Epstein case, specifically on the correct terminology to use:

The sage Confucius was once asked what he would do if he was a governor. He said he would “rectify the names” to make words correspond to reality. He understood what General Semantics teaches; if your linguistic map is sufficiently confused, you will misunderstand the territory. And be readily outmaneuvered by those who are less confused.

Mug shot of Jeffrey Epstein made available by the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Department, taken following his indictment for soliciting a prostitute in 2006.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.And that brings us to the Jeffrey Epstein scandal. In particular, the widespread tagging of Epstein as a pedophile.

No, Richard Epstein is not a pedophile. This is important. If conservatives keep misidentifying him as one, I fear some unfortunate consequences.

Pedophiles desire pre-pubertal children. This is not Epstein’s kink; he quite obviously likes his girls to be as young as possible but fully nubile. The correct term for this is “ephebophile”, and being clear about the distinction matters. I’ll explain why.

The Left has a long history of triggering conservatives into self-discrediting moral panics (“Rock and roll is the devil’s music”). It also has a strong internal contingent that would like to normalize pedophilia. I mean the real thing, not Epstein’s creepy ephebophilia.

Homosexual pedophiles have been biding their time in order to get adult-on-adult homosexuality fully normalized as battlespace prep, but you see a few trial balloons go up occasionally in places like Salon. The last round of this was interrupted by the need to take down Milo Yiannopolous, but the internal logic of left-wing sexual liberationism always demands new ways to freak out the normals, and the pedophiles are more than willing to be next up in satisfying that perpetual demand.

Liberals have proven themselves utterly useless at resisting the liberationist ratchet, so I’m not even bothering to address them. Conservatives, if you want to prevent the next turn, don’t give the pedophilia-normalizers maneuvering room. Rectify the names; make the distinctions that matter.

Epstein’s behavior is repulsive because we judge young postpubertal humans to be too psychologically immature to give adult consent, but it’s nowhere near the evil that is the sexual abuse of prepubertal children.

July 11, 2019

QotD: English is weird

English started out as, essentially, a kind of German. Old English is so unlike the modern version that it feels like a stretch to think of them as the same language at all. Hwæt, we gardena in geardagum þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon – does that really mean “So, we Spear-Danes have heard of the tribe-kings’ glory in days of yore”? Icelanders can still read similar stories written in the Old Norse ancestor of their language 1,000 years ago, and yet, to the untrained eye, Beowulf might as well be in Turkish.

The first thing that got us from there to here was the fact that, when the Angles, Saxons and Jutes (and also Frisians) brought their language to England, the island was already inhabited by people who spoke very different tongues. Their languages were Celtic ones, today represented by Welsh, Irish and Breton across the Channel in France. The Celts were subjugated but survived, and since there were only about 250,000 Germanic invaders – roughly the population of a modest burg such as Jersey City – very quickly most of the people speaking Old English were Celts.

Crucially, their languages were quite unlike English. For one thing, the verb came first (came first the verb). But also, they had an odd construction with the verb do: they used it to form a question, to make a sentence negative, and even just as a kind of seasoning before any verb. Do you walk? I do not walk. I do walk. That looks familiar now because the Celts started doing it in their rendition of English. But before that, such sentences would have seemed bizarre to an English speaker – as they would today in just about any language other than our own and the surviving Celtic ones. Notice how even to dwell upon this queer usage of do is to realise something odd in oneself, like being made aware that there is always a tongue in your mouth.

John McWhorter, “English is not normal”, Aion, 2015-11-13.

June 20, 2019

A Clockwork Orange – Dystopias and Apocalypses – Extra Sci Fi

Extra Credits

Published on 18 Jun 2019Go to https://NordVPN.com/ExtraCredits to get 75% off a 3 year plan and use code

ExtraCreditsto get an extra month free. Protect yourself online today!A Clockwork Orange reflects a cultural fear of society’s moral decay in the 1960s. Its usage of a mashup slang language known as “nadsat” illustrates the complexities of rebellious youth culture. Ultimately, Anthony Burgess’s work asks us to think about if or when free will should ever be suppressed, but the major differences between the book and the film version of this story present contrasting takeaways.

Where the dystopias of Brave New World and 1984 warned against the easy slide into totalitarianism, and painted for us worlds in which freedom is nearly a forgotten thing… A Clockwork Orange presents us with a protagonist who has almost an excess of freedom, and in doing so it shows us the shift in societal fears.